The Odyssey tells the famous story of Odysseus’ journey back to his home in Ithaca from Troy after the Trojan War. According to the traditional understanding of this narrative, divine punishment caused Odysseus to be blown all over the Mediterranean in his attempts to sail home. However, more modern research indicates that the traditional locations of Odysseus’ route are not accurate. Rather, there is a good case to be made that the majority of the route described in the Odyssey was actually very close to the shores of Greece itself.

The Traditional View of Odysseus’ Journey Through the Mediterranean

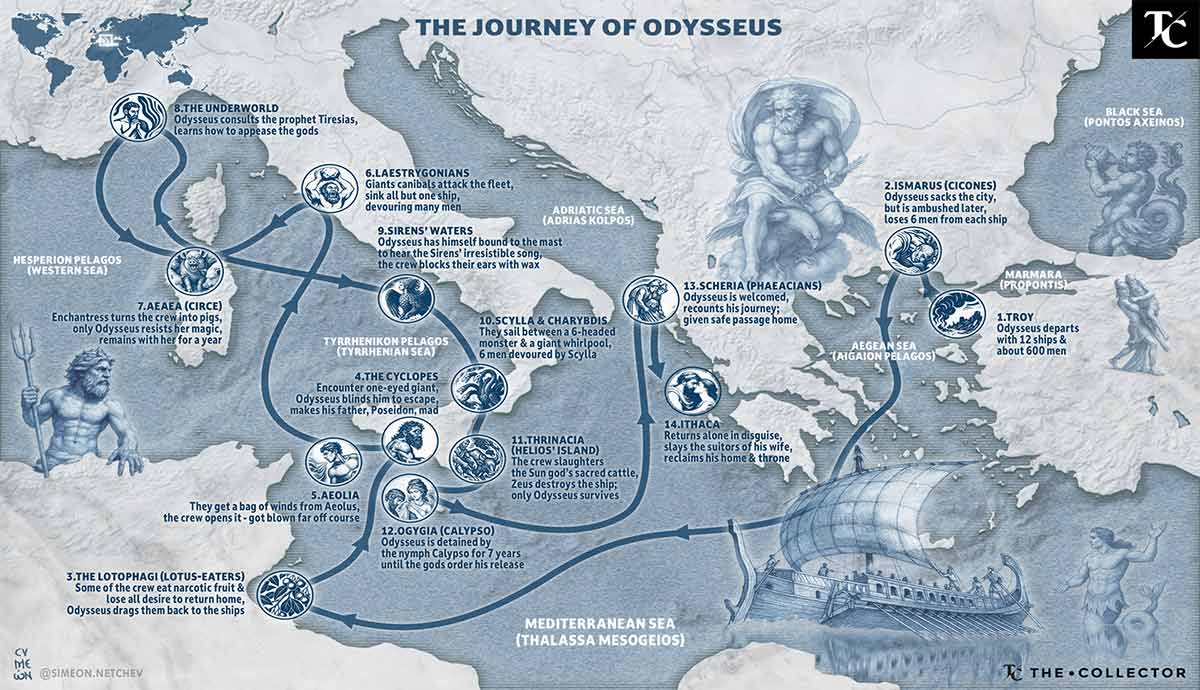

Commentaries on the Odyssey have existed since ancient times. Today, many maps are available which purport to show the journey that Odysseus took through the Mediterranean. These ancient commentaries and modern maps understand Homer to have Odysseus travel from essentially one side of the Mediterranean to the other. From a starting point at Troy, he traveled through the Aegean Sea and down to the south of Greece. While approaching the Gulf of Laconia, strong winds blew him and his fleet dramatically off course.

Due to the amount of time that Homer describes Odysseus as being blown off course, most commentators understand Odysseus to have been blown far to the west. He is generally believed to have arrived in Tunisia or nearby. From there he supposedly traveled all over the western Mediterranean, visiting places such as Italy, Sicily, and even Spain depending on the specific interpretation. For someone who was attempting to get from Troy to Ithaca, on the western side of Greece, this route has always been profoundly illogical and confusing.

Tim Severin’s Intriguing Suggestion

In more recent decades, the historian, sailor, and explorer Tim Severin attempted to combine his historical knowledge with his practical experience in the seas. He also came to be aware of the fact that one of the locations mentioned in the Odyssey, the River Acheron, seems to obviously match the river of that name in western Greece. This inspired him to look into the true route of the Odyssey.

One of the central tenets of Severin’s interpretation was that Odysseus was sincerely trying to get home. Hence, everything needed to be interpreted in that light. In the case of Odysseus being blown off course when attempting to round southern Greece, Severin argued that he would logically have attempted to stay on course as much as possible. He would logically have attempted to have the ships hold their position as much as they could until the wind abated, rather than simply going with the wind as other interpretations have it.

Crete, the Island of the Cyclopes

With this in mind, this would significantly reduce the distance that we can expect Odysseus to have traveled. Rather than him arriving at Tunisia, he is more likely to have arrived on the coast of Africa closer to what would later become ancient Cyrene, directly below Greece. If correct, then this would be the Land of the Lotus-Eaters.

In the Odyssey, the next location that Odysseus arrives at is a small island just next to a larger island, which is the home of Polyphemus the Cyclops. On a logical route from Cyrene back up towards Greece, one would come to the southwest corner of Crete. In Homer’s day, many centuries before an earthquake shifted the island, the Paleochora peninsula was mostly underwater and left a small island just off the southwest corner of Crete.

Notably, Severin found that local folklore on Crete speaks of a race of monstrous humans with a third eye in the forehead that live in caves and eat innocent people. The similarities with Homer’s Cyclopes are striking.

Mezapos, a Unique Site

After continuing on his journey towards Ithaca, Homer describes Odysseus as arriving at the land of the Laestrygonians. He arrived at a very distinct, circular harbor with a narrow entrance. It was large enough for the nine ships of Odysseus’ fleet, while Odysseus himself docked his ship just outside the entrance. There were cliffs surrounding the bay, from which the Laestrygonians threw rocks on Odysseus’ men when a conflict flared up.

On the logical route towards Ithaca from Crete, when following the Grecian coast, Severin came across a remarkable site. It was unlike anything he had seen in all his years as a sailor. It was Mezapos, with its unique circular bay. Exactly like how Homer had described, it was big enough for nine ships, it had a narrow entrance, and it was surrounded by cliffs. Other proposed matches for this location in the Odyssey tend to be much too big, failing to match the criteria that the Laestrygonians were able to block off the exit.

The Entrance to the Underworld

After barely escaping the Laestrygonians, Odysseus and his single surviving ship are said to have arrived at Aeaea, the island of Circe. This is not far from the coast, where Odysseus finds the entrance to the underworld by the River Acheron, the River of Lamentation, and the River of Flaming Fire.

In Epirus, western Greece, there is the River Acheron. It has a tributary river which, according to ancient records, was called the Cocytus. This is the same Greek word meaning “lamentation” used by Homer. Severin also reports that there had formerly been another connecting stream which was, allegedly, phosphorescent. There was also an oracle of the dead at this site, matching what Homer described in the Odyssey. Regarding the nearby island of Circe, the nature goddess, this would logically be a match for Paxos. This nearby island was associated with Pan, a nature god, in the later Roman era.

Of course, this leaves unexplained how Odysseus went right past Ithaca on his attempted journey home. Severin suggested that Homer combined two originally unrelated traditions. Another possibility is that the strong Sirocco wind, which blows through the Ionian Sea and causes reduced visibility, blew Odysseus right past his destination.

Scylla and Charybdis

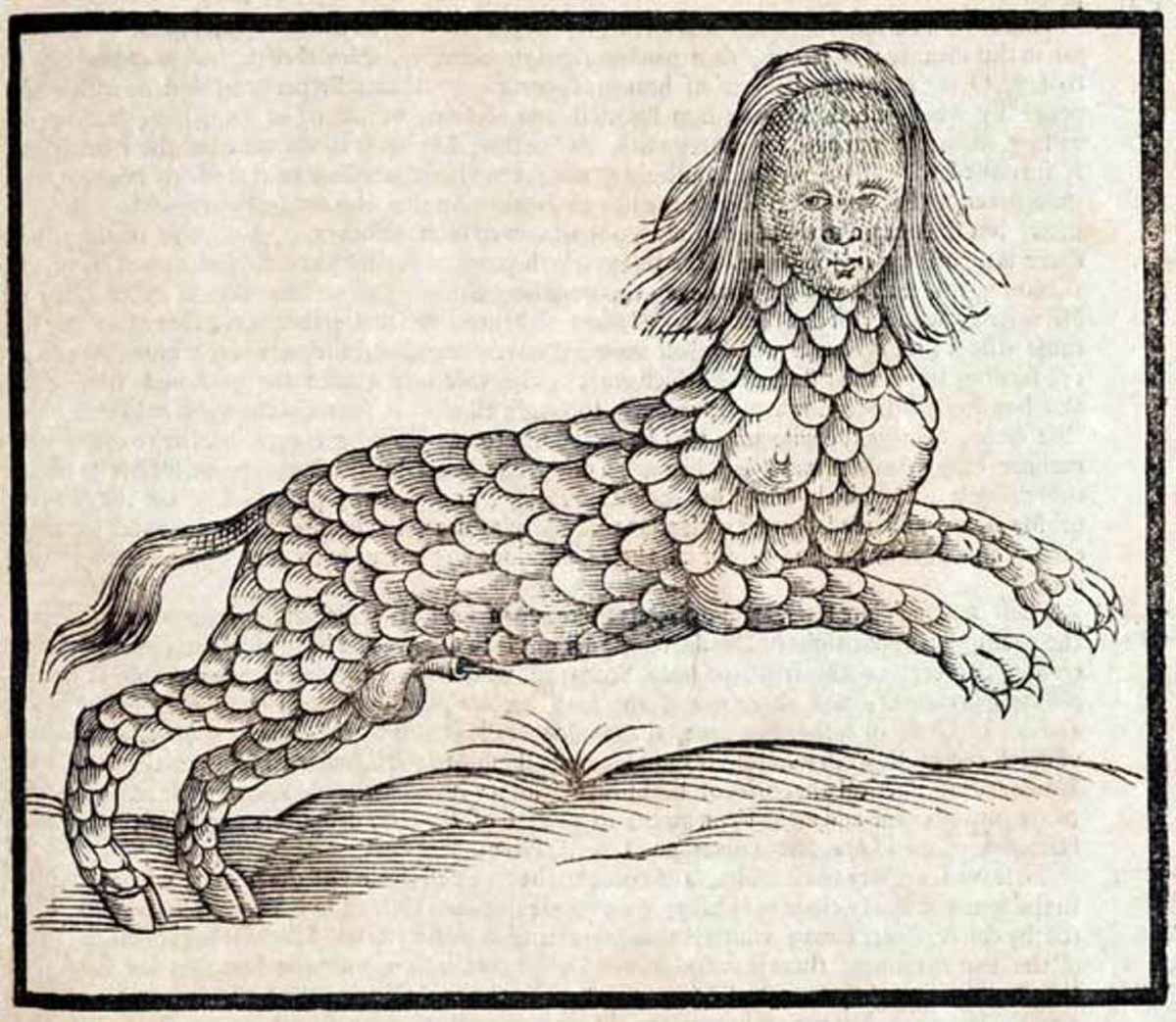

When travelling south from Paxos towards Ithaca, one has to go past Lefkada. In ancient times, this was not connected to the mainland. There was a narrow channel of water between the mainland and the island, which is now blocked off to the north. Severin concluded that this was the narrow channel in which Odysseus had to face the double challenge of Scylla and Charybdis, one on each side. Charybdis was essentially a whirlpool monster, while Scylla was a multi-headed serpentine monster which lived in a cave above the water, opposite Charybdis.

How does this match the reality at Lefkada? Severin had become emboldened by his successes up to that point, not even asking the locals if there was a cave, but where the cave was. As it happens, he was correct in his presumptions. He found that partway down the channel between Lefkada and the mainland was a notable cave on the rock face above the water.

The part of the mainland where this cave is happens to be called Mount Lamia. Significantly, the lamia is a creature from Greek and Bulgarian mythology which bears more than a passing resemblance to the Scylla described by Homer. To the Greeks, it was a serpentine monster that snatches and eats children. The Bulgarian version, no doubt strongly influenced by Greek mythology, portrays the lamia, or lamya, as having multiple heads, just like Homer’s Scylla. Perhaps even more significantly, the Greek mainland just north of the entrance to this ancient channel down the side of Lefkada is actually called Cape Skilla.

Regarding Charybdis, we can only speculate about whether or not there was a whirlpool on the opposite side of this channel in ancient times. Since the entrance is now blocked off, no one can say for sure. Nevertheless, Severin observed that there is periodically a strong outflow of water from the bay immediately north of this channel. Hence, large quantities of water would have flown south down the channel, whose natural surface current is to the north. This would, quite plausibly, have caused a whirlpool.

Where in the Mediterranean Did Odysseus Really Travel?

In conclusion, where in the Mediterranean did Odysseus really travel? Did Odysseus’ journey really take him all over the Mediterranean, potentially even as far as Spain? Or, rather, was Homer attempting to describe a much more logical attempt from Odysseus to get back to Ithaca? We may never know the answer, but the late Tim Severin made an entirely plausible, convincing case that most of the route in the Odyssey takes place not far from the Greek mainland. He rejected the common interpretation of Odysseus allowing himself to be blown many hundreds of miles off course. Rather, he argued that he would have tried to keep his position as much as possible.

According to this theory, the island of Polyphemus the Cyclops was Crete. The land of the Laestrygonians was Mezapos, in Greece itself. The entrance to the underworld was also in Greece, and Scylla and Charybdis were in the narrow channel between Greece and Lefkada. If correct, then this would mean that Odysseus hardly traveled around the Mediterranean at all.