From the New Kingdom (c. 1550-1070 BCE) to the Ptolemaic Kingdom (305-30 BCE), the bond between the Egyptian pharaoh and the god Amon-Ra was celebrated at the Temple of Luxor (Thebes). Once a year, Amon-Ra traveled from his principal Karnak Temple (ipet-sut, “the most revered place”) to the Luxor Temple (ipet-resyt, “the southern sanctuary”). Here, the reigning king and his ka (soul) united with the deity, a union from which royal power and the entire cosmic order emerged completely renewed.

Origins and Meaning of the Festival

The term “Opet” means “secret chamber.” It refers to the hidden rooms of the Temple of Luxor where the most important rituals of the Opet festival took place. Here, the powers of Amon-Ra were transferred to the pharaoh, he was ceremoniously crowned again through complex rituals, and he “met” the god in the most inaccessible areas of the temple. The ceremony ensured Amon-Ra’s regeneration through numerous offering rituals, and in return, the king maintained his divine status and right to rule.

Furthermore, in the Egyptian pantheon, there was a deity called Opet (also called Apet, Ipet, or Ipy), depicted as a female hippopotamus with pendulous breasts, standing on her leonine hind legs, with human arms and lion-like paws. She had a crocodile’s tail or sometimes a crocodile lying on her back. As a protector of pregnant women and newborns, she assumed particular importance in Thebes, especially in popular worship. She was considered the mother of Osiris and became the personification of the city.

Although the deity did not play an active role in the Opet festival, the fact that the festival bore the name of a fertility goddess clearly shows the purpose of the ritual. It served to regenerate the god and the royal ka, as well as the entire cosmic cycle.

The ka was one of the three abstract entities that formed the individual, along with the ba and the akh. The ka was associated with the body only temporarily. When the two were separated after death, the ka entered a new form of life. The ka belonged to a family and was infinitely replicated within it. The ka was a vital force that was inherited. The living were the current representation of the ka of their ancestors. In a similar way, the ka of a god temporarily occupied his statues, and the royal ka inhabited and empowered the body of a king.

The Temple of Luxor

Every temple in Egypt was a microcosm, a mirror image of a higher order. Ma’at, the cosmic order, reigned in each temple, which repelled the chaos of the secular world through its architectural barriers. A temple was the dwelling of the god and the place of the sp tpy, the “first time,” or Creation. The latter characteristic was attributed, starting from the New Kingdom, specifically to the Temple of Luxor, which was considered to be the birthplace of the sun god Amon-Ra and the primordial mound from which he created the world.

Since the unification of the country (around 3100 BCE), the pharaoh was seen as being close to the gods. This bond between royalty and divinity became stronger in the New Kingdom. This was a very prosperous time for Egypt, thanks to numerous military victories in Libyan and Syrian-Palestinian territories and the consequent wealth derived from the spoils of war. Stability and prosperity lent greater credibility to royal power, which was so closely associated with divine power that the places of worship were dedicated to both gods and pharaohs.

Unusually, the Temple at Luxor was dedicated exclusively to Amon-Ra, and not associated with a specific pharaoh. Rather it was a place to worship royalty as a concept. Very few pharaohs contributed to the construction and decoration of the Luxor temple, especially when compared to Karnak, which was contributed to by approximately 30 pharaohs. Nevertheless, it was the site of the most important religious event in the Egyptian calendar.

An Event of Vital Importance

The main aim of the Opet Festival was to affirm divine royalty and reconfirm the earthly powers of the pharaoh. It also had a strong cosmic significance, as it allowed Amenemopet (the manifestation of Amon in the Luxor Temple) to regenerate, Amon of Karnak to be reborn, and the cosmos to recreate itself. In fact, while linear time was a prerogative of the secular world, sacred time was abstract and cyclical, made up of perpetual rebirths. There were tangible manifestations of these rebirths such as the cycles of night and day, the phases of the moon, the changing of the seasons, and the flooding of the Nile.

The Opet Festival was the longest in the Theban festive calendar. It began on the 15th or 19th day of the second month of the first season, the flooding season named Akhet. The festival initially lasted eleven days, but it was later extended to 24 days, and then 27 days under Ramses III in the 12th century BCE. The pharaoh traveled from Karnak to Luxor as part of a procession, accompanied by the boats of the Theban triad. Once in Luxor, the pharaoh met Amon-Ra, his divine father, and then returned to Karnak.

Surviving testimonies regarding the procession are vague. However, decorations of the Red Chapel of Hatshepsut (c. 1507-1458 BCE) in the Karnak Temple, decorations made during Tutankhamun’s reign (c. 1332-1323 BCE) in the Luxor Temple’s colonnade, and the architectural structure of the temple, particularly the Ramesside courtyard (c. 1279-1213 BCE), provide a fair amount of pictorial and textual material to reconstruct the ceremony.

The Festival Inside the Complex of Karnak

The procession probably began in the Akhmenu, which was the area within the Karnak complex most closely linked to the Temple of Luxor. This is evidenced by the fact that Alexander the Great later restored only the boat sanctuary of Amenhotep III in Luxor and the Amon chapel in the Akhmenu, thus paying special attention to the two endpoints of the procession. The Theban divine triad, composed of Amon, Mut, and Khonsu, resided in the Karnak Temple. The king left offerings for the triad boats, still on their pedestals in an open courtyard, where the royal boat was also placed, putting the king on the same level as the gods.

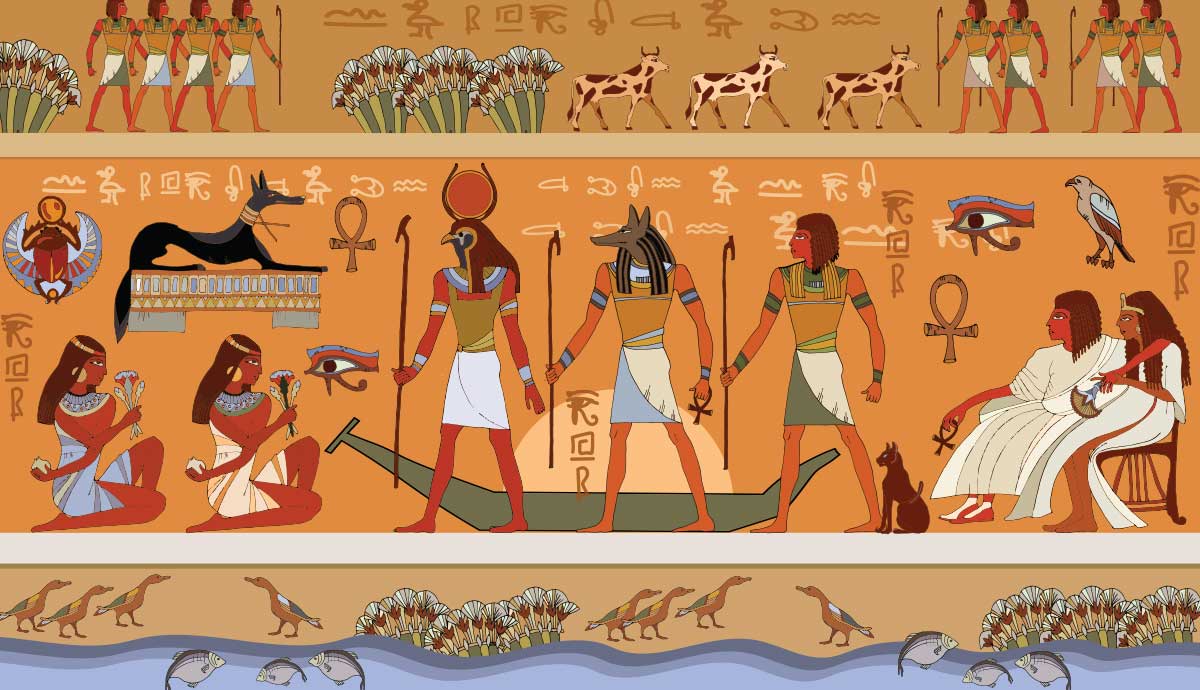

The boats were then carried on the shoulders of priests with shaved heads. Four “prophets,” one of the highest priestly offices, recognizable by the leopard-skin mantles they wore and also their shaven heads, walked beside the boats, “assisting” the deities who resided in them and giving them incense and water as gifts during the journey.

The procession moved westward. The king and the priests moved to the temple of Khonsu, where the statue of the god’s ka joined the parade after receiving offerings from the king. From there, through an avenue of ram-headed sphinxes, they arrived at the complex of Mut, where the same ritual was repeated. The goddess received offerings, and the statue of her ka joined the procession. At this point, the parade proceeded towards Luxor. There were two ways to reach the temple, by land or by river. If the Nile route was chosen, they would head from the temple of Mut towards the quay to the west. Here the ritual boats were lifted onto vessels, which were either sailed or rowed, and were accompanied by the pharaoh and the priests.

Procession Outside the Temples

A big crowd gathered enthusiastically to watch the procession. Moreover, Egyptian and foreign contingents, fully equipped for war with chariots and horses, marched parallel to the boats, adorned with colorful feathers and carrying banners. There were musicians playing lyres, shaking sistrums, and rolling drums. Acrobatic dancers were dancing to intoxicating rhythms, whilst trumpeters were marking every moment of the ceremony, amidst people singing and applauding.

Upon arrival at the Temple of Luxor, waiting for the boats and the king were princes, princesses, and high dignitaries. They gave bouquets of flowers and livestock to be sacrificed. The boats, lowered from the vessels, rested at the entrance of the temple, with all the received offerings piled up in front of them.

If the land route was chosen instead, they would traverse the avenue of human-headed sphinxes that led from the Temple of Mut to the Temple of Luxor. The procession would stop at boat stations, which were small sanctuaries placed along the route where the boats rested and received offerings. There were a total of six stations, likely all built at the behest of Queen Hatshepsut (c. 1507-1458 BCE). It is not possible to determine the criteria behind the choice of the land or the river route. The water level of the Nile, the desire to showcase new and more lavish vessels, or simply the taste of the individual pharaoh might have been considerations.

The Festival Inside the Temple of Luxor

The procession entered through the western door of the courtyard, facing the quay if coming from the Nile, through the pylon if the land route was chosen. Once inside, the first stop was the triple chapel set against the back of the west tower of the pylon, where the boats received further offerings and “rested.” After that, the procession left the courtyard and entered the temple, moving towards the sanctuary of the boat. The crowd had access to this first part of the temple. People witnessed the pompous entrance of the king and the gods into the temple, only to see them disappear into the darkness of the colonnade.

Once they crossed the hypostyle, the king and his entourage placed the boats of Mut and Khonsu into their respective chapels. It is likely that the king’s ka boat was also left behind after the statue it contained was removed so that it could proceed with the procession. They then reached the hall of the divine king, where the king was ritually “introduced” to the god Amon-Ra and purified with water. Here, the coronation ritual took place. This was a key element of the Opet festival and a moment of extreme tension, as the outcome of this ritual led either to the reordering of the cosmos or its inevitable collapse. The god, or rather a priest interpreting his role, placed the various crowns on the king’s head one by one. During each individual coronation, the king knelt with his back to Amon, who placed his hands on his head as a sign of protection. The divine ka was transferred to the pharaoh, who thereby “youthened” and increased his energy.

The procession then proceeded to the vestibule, where Amon, who remained hidden, received offerings from the king while the priests recited sacred texts. Upon reaching the naos or inner temple, the pharaoh finally opened the doors and met Amon-Ra, kneeling before his father and contemplating his beauty. The divine force instantly reflected upon the king, who thus received his final coronation and completed the renewal of his ka and received the power that would once again legitimize him in the eyes of the Egyptian Kingdom. There was probably a final part of the ceremony in which the king performed the “opening of the mouth ritual,” by touching the statue’s mouth and eyes. In this way, he “awakened” the god and restarted the cosmic cycle.

In its final stage, the procession left the Temple of Luxor to return the boats of Amon, Mut, and Khonsu to their homes at the Karnak Temple. Upon exiting the Temple of Luxor, the procession went through the same route, almost always by river, and returned to Karnak, where the gods and the king’s boats were placed back in their respective sanctuaries.

The health and vitality of the land was ensured for another year, until the ritual would be conducted all over again.

Bibliography

Arnold, D., Bell, L., Finnestad, R.B., Haeny, G., Shafer, B.E. (1997) Temples of Ancient Egypt, Cornell University Press: New York.

Bell, L. (1985) “Luxor Temple and the Cult of Royal Ka,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 44: 251-294.

Bell, L. (1994) Mythology and Iconography of Divine Kingship in Ancient Egypt, University of Chicago Press.

Donadoni, S. (1999) Tebe, Electa: Milano, 9-104.

Fukaya, M. (2020) The Festivals of Opet, the Valley, and the New Year: Their Socio-Religious Functions, Archaeopress Publishing Ltd.

Harris, J.R. (1987) The Legacy of Egypt, Oxford University Press.

Karlshausen, C., De Putter, T. (2020) “From Limestone to Sandstone – Building Stone of Theban Architecture During the Reigns of Hatshepsut and Thutmosis III,” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 106(1/2): 215–227.

Kozloff, A.P. (2012) Amenhotep III: Egypt’s Radiant Pharaoh, Cambridge University Press.

Schulz R., Seidel M. (2004) Egypt. The World of the Pharaohs, Konemann.

Silverman, D.P. (1994) For His Ka: Essays offered in memory of Klaus Baer, Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures.

Van der Plas, D. (1987) Effigies dei: Essays on the History of Religions Brill.

Wilkinson, R.H. (2000) The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt, Thames and Hudson.