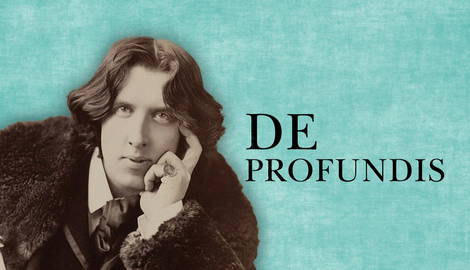

Towards the end of his prison sentence in Reading Gaol, Oscar Wilde was allowed to write again. Over the course of three months in early 1897, Wilde was given one sheet of paper per day, and each day he worked on his most overtly autobiographical work. De Profundis, as it was eventually called, appeared to be a letter to Wilde’s former lover, Lord Alfred Douglas, although Wilde was not allowed to send it to him. Before too long, it was published for the whole world to read.

Who Was Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas?

De Profundis opens with the words, “Dear Bosie.” This was the nickname of Lord Alfred Douglas, a poet and aristocrat Oscar Wilde had met just six years earlier, in 1891. At the time, Wilde happened to be finalizing the full-length novel version of The Picture of Dorian Gray, which had been serialized in a magazine throughout 1890. In a perfect playing-out of his maxim that life imitates art, he found in Bosie the living embodiment of Dorian.

Aged 20 when he met Wilde and attending Magdalen College, Oxford, Bosie was a devastatingly handsome devotee of life’s finer pleasures. He was editor of a poetry magazine, The Spirit Lamp, which specialized in works exploring the aesthetic and hedonistic tendencies of the era: the interest in vaguely denoted “sensations” and “experiences” that Walter Pater, in his influential book The Renaissance (first published 1873), had popularized among artistically inclined youths in the late 19th century.

Among these unnamed pleasures was homosexuality. It was in a similar Oxford undergraduate journal, The Chameleon, that Douglas published his poem Two Loves, soon to become infamous for its final line spoken in the voice of same-sex love: “I am the love that dare not speak its name.”

When Douglas wrote Two Loves in 1892, he had begun a relationship with Wilde, although this was not his first experience with a man. Throughout their relationship, he would continue to have encounters with other men. Douglas and Wilde also often partook together of the services of working-class men and boys.

This was not Wilde’s first same-sex experience, either. His first encounter with a man was probably around 1886, just a couple of years after his marriage to Constance Lloyd, when he met Robbie Ross, shortly to enroll at Cambridge. Ross would later become one of Wilde’s closest friends and his literary executor, though no great friend of Bosie.

As De Profundis would elaborate in great detail, Bosie—as Wilde and many of his friends felt—had not just been a selfish and demanding partner. He had landed Wilde in prison and plunged the great artist into ruin.

Why Was Oscar Wilde Writing From Prison?

It is not strictly true that Wilde had been imprisoned for his relationship with Bosie, but he may not have ended up there had it not been for Bosie. When Wilde stood before the court at the Old Bailey in 1895, accused of “gross indecency,” the charge related to a handful of working-class young men (the youngest of whom was 16) whom Wilde was alleged to have paid for sex. Bosie was not mentioned.

Wilde’s activities were not uncommon for the time, and many other men, especially among the upper classes, were able to lead gay lives, if discreetly and under constant threat of discovery by the police. It is possible that Wilde’s behavior would never have come to the attention of the law had it not been for Bosie and his father, John Sholto Douglas, 9th Marquess of Queensberry.

Queensberry was incensed by his son’s association with Wilde, blaming the poet and novelist—and, by now, hugely successful playwright—for corrupting Bosie. Throughout 1894, he waged a campaign of public insults against Wilde, even planning to attend the premiere of The Importance of Being Earnest and throw rotten vegetables at the stage. However, thanks to an advance tip-off, Wilde was able to have Queensberry banned.

Bosie’s father went about proclaiming that he would happily shoot Wilde on sight should they meet, and in early 1895, he left a calling-card for Wilde at his club which read: “For Oscar Wilde, posing somdomite [sic].”

Driven to decisive action, Wilde sued Queensberry for libel. He would later claim in De Profundis that this was instigated by Bosie, whose relationship with his father had always been tempestuous. Wilde was simply caught in the crossfire. Regardless of whether it was Wilde’s decision or Bosie’s, the libel action backfired.

To escape conviction, Queensberry and his lawyers had to prove that what he had written was true: that Wilde was homosexual. So they, along with private detectives, went about finding evidence.

It is likely that some of the boys Queensberry’s detectives found were blackmailed into testifying against Wilde. But they provided enough evidence for the Marquess to counter-sue, so that Wilde was hauled before the court for three trials in April and May 1895. As well as hearing evidence attesting that Wilde met with young men at hotel rooms (no one mentioning that Bosie was also often present), the jury had passages of Dorian Gray read to them, and Wilde was asked to comment on “the love that dare not speak its name,” the phrase from Bosie’s Two Loves.

Even when his poetry was quoted, Bosie was not mentioned by name, and Wilde was left to offer his own defense of same-sex love: an eloquent speech touching on Plato, Michelangelo’s art, Shakespeare’s sonnets, and the Biblical example of David and Jonathan, which was met by applause in the court.

Despite this response to Wilde’s performance in court, and despite the attempts of many of his friends to urge him to flee to the Continent, Wilde was found guilty and sentenced to two years’ hard labor, first at Pentonville Prison, then Wandsworth. By November, he was moved to Reading Gaol, where he served the remainder of his sentence, and, in the final few months, wrote De Profundis.

De Profundis, The Letter

De Profundis is first and foremost a letter from Wilde to Bosie, picking apart what went wrong between them. It is a plea for Bosie to support Wilde by visiting him, rather than profiting from Wilde’s newfound notoriety by publicly printing letters they had exchanged and dedicating new poems to him. It is also a plea for Bosie to reform his character, as Wilde himself has had to do during his prison sentence.

Multiple times, Wilde repeats the phrase: “the supreme vice is shallowness” (Wilde 2003, 981). This is one of his main charges against Bosie, along with selfishness and greed. Wilde calculates that, between late 1892, when their relationship began, and early 1895, when he was imprisoned, he spent more than £5,000 with Bosie, over £400,000 in today’s money.

Wilde tells a series of anecdotes to prove how decisively Bosie’s will overpowered his own throughout their relationship. Mindful as always of art’s vital role in life, Wilde emphasizes those times when Bosie’s demands kept him from his work, or when Bosie’s laziness stood in the way of Bosie’s own poetic potential.

He narrates the debacle of Bosie’s translation of Wilde’s 1893 play Salomé. Originally written in French, the play was translated into English by Bosie with Wilde’s permission. However, it was roundly criticized for being full of errors. Wilde admits the translation was “unworthy of you” and “of the work it sought to render” (Wilde 2003, 987), but explains the great lengths he went to to placate Bosie during the furor which followed.

One of the most touching anecdotes Wilde tells is of staying at Worthing while finishing The Importance of Being Earnest, when Bosie turned up unannounced. The two went to nearby Brighton together, Wilde begrudgingly putting his play aside, but Bosie caught the flu.

As Wilde describes, he nursed Bosie for four or five days, never leaving his bedside; unsurprisingly, Wilde then caught the flu himself. Rather than return the favor, Bosie left Wilde alone, dining out on his money, and writing to him: “When you are not on your pedestal you are not interesting. The next time you are ill I will go away at once” (Wilde 2003, 993).

De Profundis also gives Wilde’s side of the story of his trials and imprisonment, as well as his account of how he came to be in prison, or “the depths” as the letter’s Latin title puts it. While he blames himself for his lack of willpower, Wilde insists that he has only been imprisoned because he was caught up in Bosie and Queensberry’s family drama, used by both men as a target for attacks they really meant to direct at each other.

At no point in the letter does Wilde express regret over his sexuality, although he does theorize, in the stigmatizing language of the day, about the connections between “genius” and “perversity of passion” (Wilde 2003, 1007). His regret is that he allowed himself to be bewitched, again and again, by Bosie, until he became so deeply ingrained in the Queensberry family hatred that he found himself pilloried and publicly vilified.

In one of the letter’s saddest moments, Wilde describes being transferred from Wandsworth Prison to Reading Gaol. This was a public journey which involved being left on the platform at Clapham Junction for half an hour, where members of the public laughed and jeered at him. “For a year after that was done to me,” Wilde writes, “I wept every day at the same hour and for the same space of time” (Wilde 2003, 1040).

De Profundis, The Essay

While De Profundis would still be of literary interest if it were only a letter, given the circumstances in which it was written, it has further literary interest as essentially the last of Wilde’s great essays. Amidst the chastising directed at Bosie and the regrets directed at himself, Wilde spends long passages of the letter theorizing—sometimes on his usual themes, sometimes on ideas that have come to him during his time in prison.

“I was a man who stood in symbolic relations to the art and culture of my age” (Wilde 2003, 1017). Wilde reflects on his legacy, his popularization of a new way of imagining the role of art in everyday life, his dedication to living out his philosophy by “treat[ing] art as the supreme reality, and life as a mere mode of fiction” (Wilde 2003, 1017).

In this sense, De Profundis is Wilde’s most extended reflection on his own work, a reiteration of his devotion to paradoxes, artificiality, and a witty turn of phrase: all things that made him beloved of contemporary audiences.

“I am far more of an individualist than I ever was […] My nature is seeking a fresh mode of self-realisation” (Wilde 2003, 1018). Self-realization was one of Wilde’s constant themes, underlying the doppelgänger story of Dorian Gray and the identity-switching of The Importance of Being Earnest. He had mused extensively on individualism and self-realization in the essay The Soul of Man Under Socialism (1891), a work that prefigures De Profundis in some ways.

In both texts, Wilde insists that one’s highest duty to the self is to realize it—to discover who one truly is. With his usual relish for paradox, he claims that one must discover the self by reinventing it, posing, and wearing masks.

In the middle passages of De Profundis, when it becomes easy to forget that we are reading a letter rather than an essay, Wilde speculates about how suffering and sorrow might intensify one’s character. As he had done in The Soul of Man Under Socialism, he turns to Jesus Christ as the best example of a fully realized individual, whose self-knowledge has come through suffering.

These passages have led some readers to suggest Wilde is painting himself as a martyr, with the anecdote about his journey from Wandsworth to Reading and being jeered at by crowds forming a kind of modern retelling of Christ’s Passion.

Wilde certainly wants to invoke some comparison between himself and Christ, whom he considers the best of all poets, and to transform his own suffering so that it fulfils some kind of redemptive function. But these passages in De Profundis should be placed in the wider context of Wilde’s writings.

He had written about Christ as the supreme individualist before, when he had no reason yet to think of himself as a martyr. He was also hoping, as he divulges in De Profundis, to write about him again, once out of prison, on the subject “Christ as the precursor of the Romantic movement in life” (Wilde 2003, 1034).

In that sense, this long digression could be Wilde flexing his artistic muscles, testing the ground for his post-prison writing, as much as anything else. As it was, though, he never got round to this last work on Christ.

What Happened to the Letter?

In one of literary history’s great happy accidents, we are only able to read De Profundis now because, firstly, Wilde was forbidden by the prison authorities to send it to Bosie, and secondly, his alternative arrangements for the letter did not go quite to plan.

In May 1897, Wilde was released from Reading Gaol and was allowed to take the manuscript of De Profundis with him. He was met by Robbie Ross, to whom he gave the manuscript, asking him to make a copy of it and send the original to Bosie.

This is where the stories of the two men closest to Wilde, Bosie and Ross, diverge. At one time, Bosie insisted he had not been sent De Profundis, and was not even aware it existed until much later. In yet another libel trial in which he was embroiled, in 1913, Bosie made a slightly different claim: Ross had sent him a heavily edited copy, which he had immediately burnt without reading.

According to Ross, this was exactly what he had feared when Wilde instructed him to send the original manuscript to Bosie. Therefore, anticipating that De Profundis might form an important cornerstone in Wilde’s artistic legacy and wishing to preserve it, he kept the original and sent Bosie a copy instead.

De Profundis then emerged in a series of edited versions over the coming decades. An initial publication in 1905, just over four years after Wilde’s death, omitted all references to the Queensberry family. By 1922, as Ross made his way through Wilde’s complete works as his literary executor, more of the letter was published, but the complete manuscript remained private.

Ross donated it to the British Museum on the condition that it would not be made public until 1960. Unbeknownst to Ross at the time, the lifting of restrictions on the manuscript would soon coincide with a renewed interest in Wilde following the partial decriminalization of homosexuality, including the repealing of the act under which he had been imprisoned, in Britain in 1967.

Before 1960, the only time anyone had access to the unabridged text of De Profundis was during Bosie’s 1913 libel trial, when it was read out to him. Unwilling to listen, he even, at one point, left the courtroom. He remained insistent that he had never read the letter, so he never had a chance to take Wilde’s advice to him.

In a sad but inevitable twist, Wilde did not take his own advice either, nor act upon his resolve to realize his true self by repudiating Bosie. Towards the end of 1897, with Wilde now living in exile on the Continent, the former lovers reunited in Naples.

Before the prison sentence, they had survived on Wilde’s money; now, both were insolvent. Whatever they hoped to recapture was lost forever, as was Wilde’s ability to create. Apart from the great tragic poem The Ballad of Reading Gaol, De Profundis was his last finished work.

It was almost as if Wilde had, with his unerring eye for the dramatic, orchestrated it all, in spite of the chaos and tragedy, making his final work a definitive statement on the intertwining of his life, his loves, and his art.

Bibliography

Wilde, Oscar (2003). ‘De Profundis,’ in The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde. London: HarperCollins.