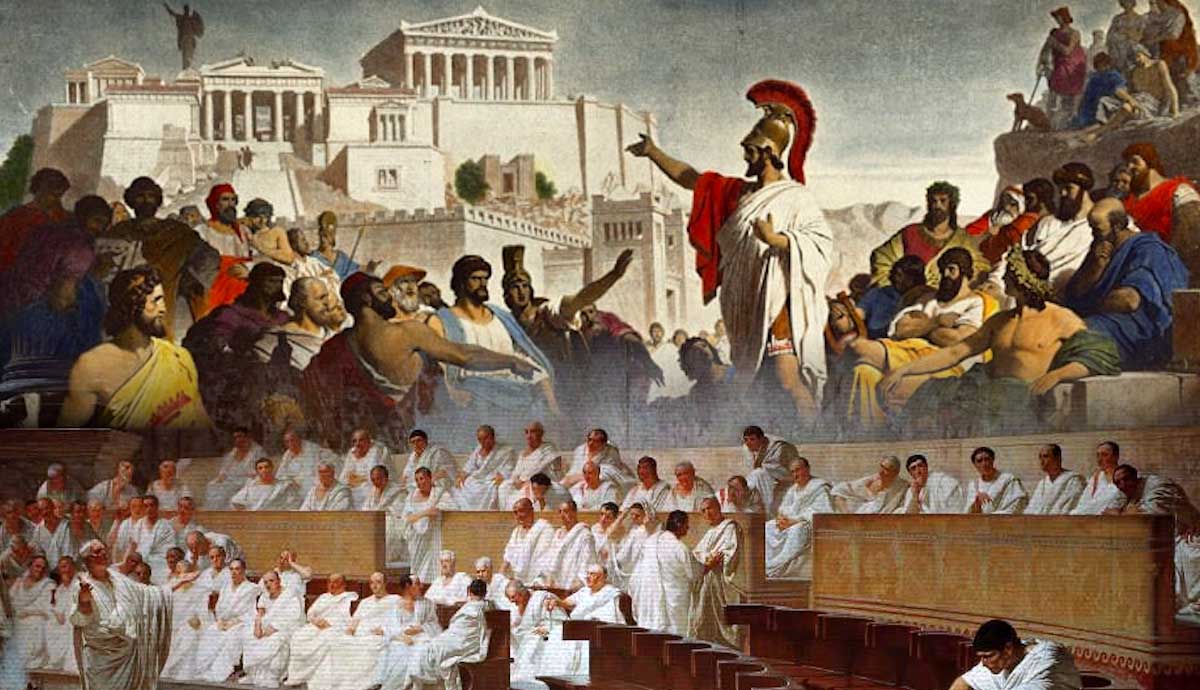

Collective governing, whether through democracy in classical Athens or oligarchy in the Roman Republic, meant that public speaking and persuasion were important. Methods of persuasion were pioneered and refined to build credibility, create the appearance of logic, and use people’s emotions to bring them to a desired conclusion. These techniques are preserved and exemplified in speeches such as Pericles’ Funeral Orations, Demosthenes’ Philippics, Cato the Elder’s speeches against Carthage, and Cicero’s Catilinarian Orations. Persuasive rhetoric was elevated to a philosophy by the likes of Aristotle, and techniques perfected in ancient times are still used today. Below are eight techniques of persuasion from antiquity.

Ancient Modes of Persuasion

In his Rhetoric, one of the most influential texts on the subject, Aristotle outlines three modes of persuasion. In Aristotle’s view, rhetoric was a key element of philosophy alongside logic and dialectic. Describing these modes, Aristotle states that Ethos “depends on the personal character of the speaker”, Pathos on “putting the audience into a certain frame of mind,” and Logos on “the proof, or apparent proof, provided by the words of the speech itself.” The successful application of these three persuasive approaches can be seen in some of the most influential speeches throughout history.

Aristotle’s view contrasted with Plato’s view, which characterized rhetoric as potentially dangerous and misleading. This view was influenced by misleading approaches taken by sophists, which he felt were responsible for the execution of his mentor Socrates.

1. Pathos

In rhetoric, the term Pathos refers to arguments that are intended to appeal to the emotions of the audience. The Greek word páthos has a range of meanings, including a “strong feeling” or “emotion.” It is the root of the words sympathy and empathy, reflecting their meaning in the context of rhetoric. This mode of persuasion often involves the speaker striking a chord with the audience’s concerns or value systems.

During the Third Punic War, Cato the Elder famously concluded all of his speeches with the Latin phrase “Carthage delenda est”, which translates to “Carthage must be destroyed”. This repeated refrain was meant to inflame the fear and anger of the Romans against their old enemy.

2. Ethos

Ethos refers to a speaker’s ability to convince an audience of their authority to speak on the subject. In Greek, ethos means “character” and has its etymological roots in the word ethica, which specifically describes “moral character.” In Rhetoric, Aristotle describes a range of ways that a speaker can gain credibility with an audience, including demonstrating expertise and showing moral character.

The Greek philosopher Isocrates argued that a speaker’s ethos or lack thereof is often partly established before they have begun speaking, based on an audience’s knowledge of their past actions.

3. Logos

Logos refers to arguments that appeal to logic or present an ostensibly logical line of argument. This is closely linked to ethos, as logical arguments will typically increase the credibility of the speaker. In a modern context, this could include the use of statistics or data to support an argument. Speakers can illustrate a process of logical reasoning to encourage the audience to arrive at their desired conclusion. On the negative side, logical fallacies can also be compelling.

Logical debates formed a central theme of many Ancient Greek plays. Many of Sophocles’ plays included discourse similar in format to a Socratic dialogue, in which questioning was used to reveal inconsistencies in logic. This approach was also often satirized in classical Athens. For example, Aristophanes presented Socrates as a sophist using the appearance of logic to mislead. In Plato’s Apology, this play is described as a contributing factor to Socrates’ trial and execution. The allegation that Socrates was a sophist was damaging because sophists were considered to use ostensibly logical statements to put forward misleading and inaccurate arguments. Plato explained that while philosophers, like Socrates, used logic to seek truth, Sophists were only concerned with winning arguments.

4. Kairos

Kairos refers to an opportune moment within an argument or debate. The ancient Greek word translates to “the right time.” Rhetoricians acknowledged the unique character of individual speeches and debates and highlighted the need to react as individuals presented. Aristotle related Kairos to the three modes of persuasion, as the individual circumstances of a speech will determine which mode of persuasion is most effective at a given time.

5. Hypophora

Hypophora is a rhetorical technique in which the speaker poses a question to the audience and then proceeds to answer it. This question and answer are contrived to give the appearance that the speaker’s ideas stand up to questioning. Hypophora differs from a rhetorical question that the speaker leaves unanswered. Introducing a question can have the effect of engaging the audience with an issue. This device frequently appears in literature, providing structure to a monologue.

6. Anaphora

Anaphora is a widely used device that involves using a repeated refrain throughout a speech for emphasis. In Greek, anaphora translates to “carrying back,” in this context, back to a statement made earlier in the speech. This device is frequently also used as a literary device, as it can draw emphasis or build momentum in a passage of text. A famous example of anaphora is in A Tale of Two Cities, where Charles Dickens introduces apparently disparate ideas, drawn together through an anaphoric device in the opening statement, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.”

This rhetorical device has been used frequently in modern speeches. One of the most famous 20th-century examples was Martin Luther King Jr’s “I have a dream speech.” This was one of a wide range of powerful rhetorical devices anchoring the series of statements in a powerful call for equality and justice. This approach also built momentum and emphasized the phrases that followed. This device is frequently used by preachers delivering sermons and is one example where King drew on his experience as a religious leader.

7. Epiphora

An epiphora, also known as an epistrophe, is similar to an anaphora but with the repeated refrain made at the end of a phrase rather than the beginning. The term’s etymology is the Greek word epistrophē, which translates to “turn around.” This device places a similar emphasis on the repeated refrain.

As well as being a powerful rhetorical technique throughout antiquity, this device has been used widely in more recent history. A famous example is in the Gettysburg Address, where Abraham Lincoln stated that “government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

8. Aporia

In rhetoric, Aporia refers to the speaker expressing doubt, often as a pretence to achieve a wider objective. This can result in engaging the audience in a problem or providing the opportunity for the speaker to explore an issue in more depth. This device was used by Demosthenes in his famous speech On The Crown, in which he opens by stating that he does not know where to begin questioning which of the numerous infractions of his opponent should be used as a starting point.

In a nutshell

| Technique | What it is | How it persuades |

|---|---|---|

| Pathos | Emotional appeal | Activates feelings (fear, anger, compassion) so the audience wants the conclusion |

| Ethos | Credibility/character appeal | Makes the audience trust the speaker as informed, moral, or authoritative |

| Logos | Logical appeal | Uses reasoning, evidence, and structure to make the conclusion feel inevitable |

| Kairos | The “right moment” | Wins by timing: choosing the best moment/angle for this audience and situation |

| Hypophora | Ask-and-answer | Controls the conversation by raising a question and immediately supplying the “best” answer |

| Anaphora | Repetition at the start | Builds rhythm and momentum; makes key points memorable and emphatic |

| Epiphora (Epistrophe) | Repetition at the end | Emphasizes the repeated ending as the takeaway; creates a strong cadence |

| Aporia | Expressed doubt (often strategic) | Invites the audience into the problem, signals “honesty,” or sets up a stronger point |