Hidden away among the many King Louis is one of French history’s most interesting characters: King Philip IV. Known as Philip the Fair, he ruled from 1285 to 1314, an incredible period in French history. He was also known as the Iron King, which was a testament to the way that he ruled. One of the most interesting aspects of Philip’s reign was that he fathered three kings of France, and one Queen of England—something that other monarchs have seldom achieved. Read on to find out about the incredible life and reign of this brilliant medieval French king.

Philip’s Early Life

Philip was born into the House of Capet in the spring of 1268 in the Palace of Fontainebleau, France. His father was King Philip III of France (r. 1270-85) and his mother was Isabella of Aragon.

Philip’s early life was fairly tumultuous. In 1270, his grandfather, King Louis IX, died while on crusade, and his father became king. In January 1271, when Philip was not quite three years old, his mother died while horseriding, and she was pregnant with her fifth child.

Just a few months later, one of Philip’s younger brothers, Robert, died. On August 15 of the same year, Philip’s father was formally crowned King Philip III of France at Rheims, and he married six days later.

In May 1276, Philip’s older brother, Louis, the heir apparent, died. This then made Philip the heir to the French throne. A rumor circulated that Philip and Louis’s stepmother, Marie, had poisoned Louis as she had recently given birth to her own son, who could be in contention to become king. However, this is unlikely, as Philip lived to become king, and his younger biological brother Charles also lived well into adulthood.

Little else is known about Philip’s early years, save that he received a good education under the guidance of his father’s almoner, Guillaume d’Ercuis.

On August 16, 1284, aged 16, Philip married Joan I of Navarre, a marriage which would last until her death in 1305. The couple were known to be genuinely devoted to each other, with Philip refusing to marry after her death, even for lucrative political and financial rewards.

Philip IV’s Early Reign

Philip III died of dysentery while on the Aragonese Crusade aged 40 on October 5, 1285, leaving the throne to his 17-year-old son, who was officially crowned as King Philip IV of France at Reims on January 6, 1286.

Philip was determined to strengthen the monarchy throughout his reign at the expense of reducing the wealth and power of the clergy and nobility. Despite this, Philip was known to be pious and donated a lot of money to the Church throughout his reign.

Philip’s desire to strengthen the monarchy ultimately led to the transformation of France from a feudal state into a centralized early modern state, and he became one of the most highly-revered European monarchs of the 13th and 14th centuries.

Because of his ambitious nature, he was very well respected around Europe, and, similarly to many of his contemporaries, he sought to place as many of his relatives on various European thrones as possible.

Troubles With England

As Duke of Aquitaine, King Edward I of England was supposed to pay Philip homage, but after the Crusaders lost Acre in 1291, the two kings began to show animosity toward each other.

In 1293, La Rochelle, a coastal town in France, was sacked by English sailors, and Philip summoned Edward to France to offer an explanation. Philip only addressed Edward as a vassal and a duke, yet despite this insult, Edward wanted to avert war at all costs.

An agreement was made between the two monarchs that Edward would temporarily relinquish Gascony to Philip, and that Edward was to marry Philip’s sister, Margaret.

On May 19, 1294, Edward (after refusing to attend Philip’s court earlier in the year) was relieved of Aquitaine, Gascony, and other Plantagenet territories in France. In response, Edward renounced his homage to Philip and began to prepare for war. This conflict would rage on until 1303 and became known as the Gascon War.

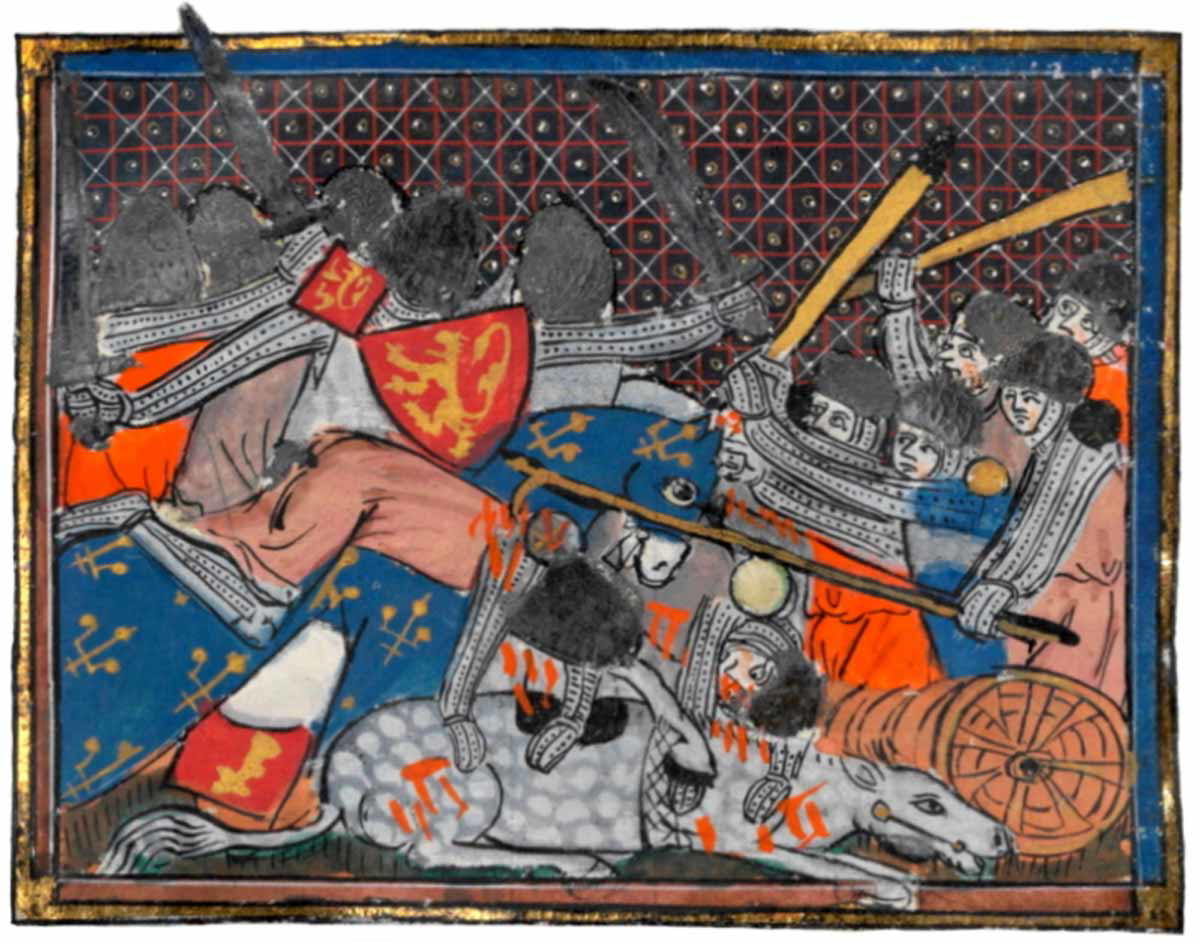

The Gascon War (1294-1303)

France initially turned to Scotland for support in the war, renewing the Auld Alliance, as Edward had been busy fighting the Scots in the First Scottish Wars of Independence at the same time, and now had war on both fronts of his kingdom to deal with.

However, France was not just fighting one battle; Edward assisted the Kingdom of Flanders in their war against the French, so France ended up fighting wars on two fronts.

The Gascon War was arguably Philip’s biggest humiliation as king of France. Not only did the war cost thousands of lives, and was incredibly expensive, but Philip ended up coming out of it worse off than Edward.

The French defeat at the Battle of the Golden Spurs on July 11, 1302 was the final nail in the coffin which forced Philip to give Aquitaine back to Edward.

To seal the deal at the end of the war, Philip’s daughter Isabella was betrothed to Edward’s son, Edward, who would go on to rule as King Edward II of England. This marriage produced an heir (the unborn but future King Edward III of England), who would therefore have a rightful claim to the French throne through his mother. Who knew at the time, then, that this decision of betrothal would eventually lead to one of the bloodiest conflicts in European history: the Hundred Years’ War?

The Beginning of the Avignon Papacy

As mentioned above, Philip was an incredibly strong leader. Sometimes, he was too strong for his own good.

He attempted to impose state control over the Catholic Church in France, which led to conflict with Pope Boniface VIII.

This conflict turned violent, and the pope’s residence at Anagni, just south of Rome, was attacked in September 1303 by French forces supported by the Colonna family.

This put the pope in great danger, and he was even captured before being released a few days later.

Naturally, he had to move. The move eventually became known as the Avignon Papacy (1309-76), as seven successive popes resided in Avignon, rather than Rome. At the time Avignon was in the Holy Roman Empire, but it is now in modern-day France.

Relations With the Mongols

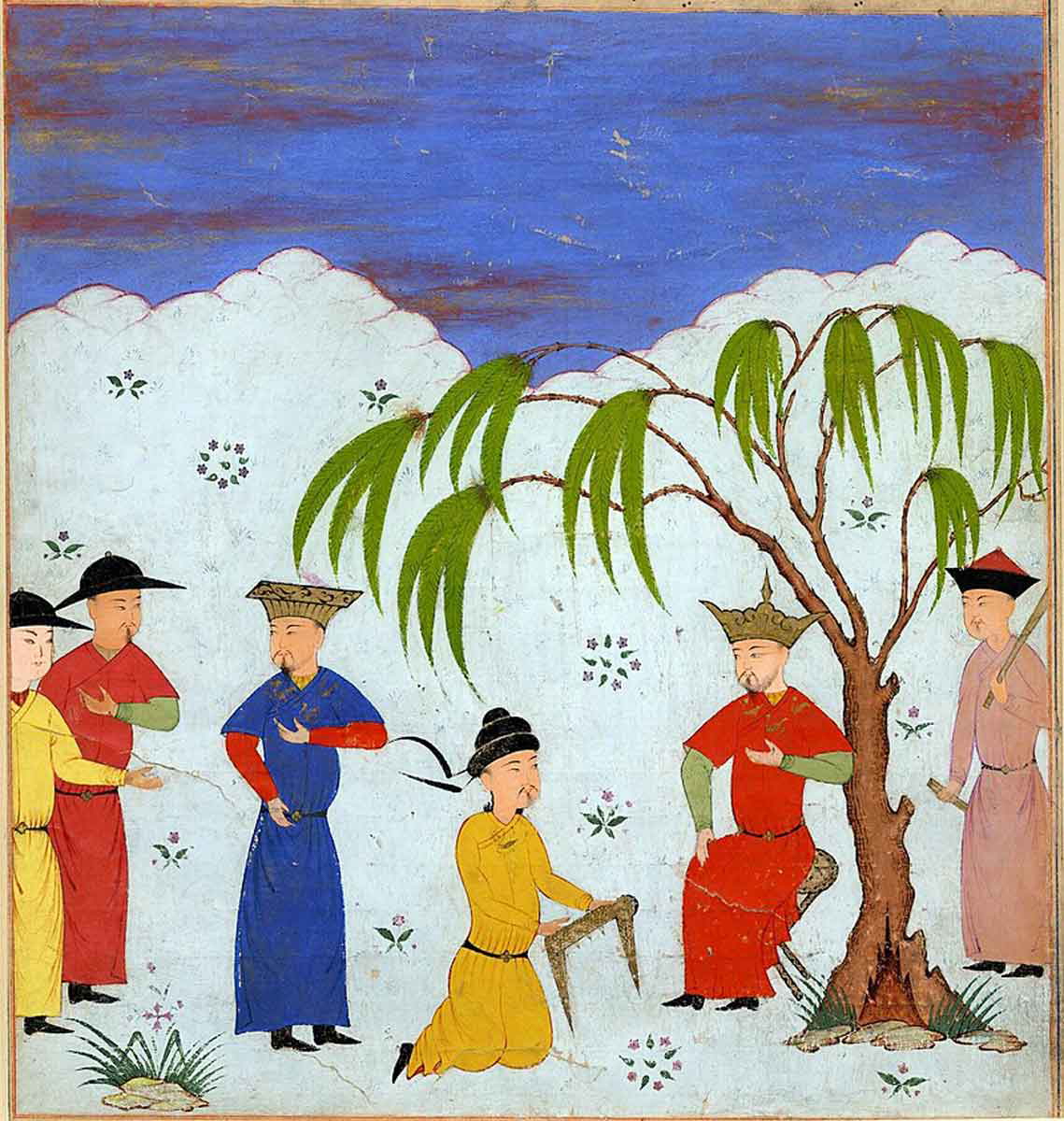

Another key aspect of Philip’s reign was the correspondence between himself and the greatest force from the East that Europe had ever seen: the Mongols.

In April 1305, the Mongol leader, Öljaitü sent letters to Philip as well as to Edward I and Pope Clement V, offering a collaboration between the European Christian nations and the Mongols against the Mamluk Turks.

While this is a mere footnote in Philip IV’s reign, it nevertheless shows how powerful he was as a monarch, that a Mongol leader reached out to him for assistance. While a crusade was planned but never materialized, Philip (against the will of his advisers) took the cross, pledging himself to go on a crusade should the opportunity arise.

The End of the Knights Templar

One of the major stains on King Philip IV’s reign was how he brutally ended the Knights Templar.

The Knights Templar were formed in 1118 as a monastic military order, designed to protect Christian soldiers while on Crusade in the Latin East.

However, through his various military campaigns and the devaluation of the French currency, Philip was in a lot of debt, much of which he had borrowed from the Knights Templar.

Many of the services that the Knights Templar had originally offered had largely been replaced by banking, and crusading fever was not as strong as it had been in the 11th and 12th centuries. Philip used this decline in their services as an excuse to have them eradicated as an order.

On Friday the 13th of October 1307, at dawn, under instruction from Philip IV, hundreds of Templars in France were simultaneously arrested. They would then be tortured into confessing their alleged heresy.

Pope Clement V was a weak pope, and Philip frequently saw him as a puppet. Clement wanted the Knights Templar to have fair trials (as they were originally only answerable to the Pope), but Philip reminded him how many of them had admitted their heresy (with the aid of torture). Many of the Knights were burned at the stake due to their confessions before proper trials could be held.

Jacques de Molay, and Geoffroi de Charnay, the last leaders of the Templar, were formally burned at the stake in March 1314, bringing an end to one of the greatest Crusading organizations of the Middle Ages.

The Tour de Nesle Affair

In 1314, two of Philip’s daughters-in-law (Margaret of Burgundy, married to Prince Louis and Blanche of Burgundy married to Prince Charles) were accused of adultery. Their alleged lovers were first tortured, before being flayed and then executed, as a way of sending a message to anyone who would be unfaithful to a member of the French royal family.

Later on, Philip’s other daughter-in-law, Joan II, Countess of Burgundy (wife of Prince Philip) was accused of knowing about the affairs and doing nothing about them.

Philip IV’s Death and Legacy

Later in the same year, Philip had a stroke while out hunting in the Forest of Halatte. The stroke severely inhibited him, and he ended up only surviving for a few weeks. He died, aged 46, in Fontainebleau. He was succeeded by his eldest son, Louis, who would go on to be crowned King Louis X of France.

The legacy that Philip IV left behind cannot be understated. He was a strong monarch, who helped to transform the country through his leadership.

While there were some dark moments, such as the Gascon War and the Knights Templar affair, he nevertheless left France a stronger country than the one he had inherited from his father.

He also went on to father three future kings of France: Louis X (r. 1314-16), Philip V (r. 1316-22), and Charles IV (r. 1322-28). On top of this, the diplomatic relations that he formed with his daughters showed France as a medieval European powerhouse.

While some of these relations unfortunately led to the Hundred Years’ War and some bad years for France, Philip IV’s legacy is that, without question, he was one of the most influential monarchs in French