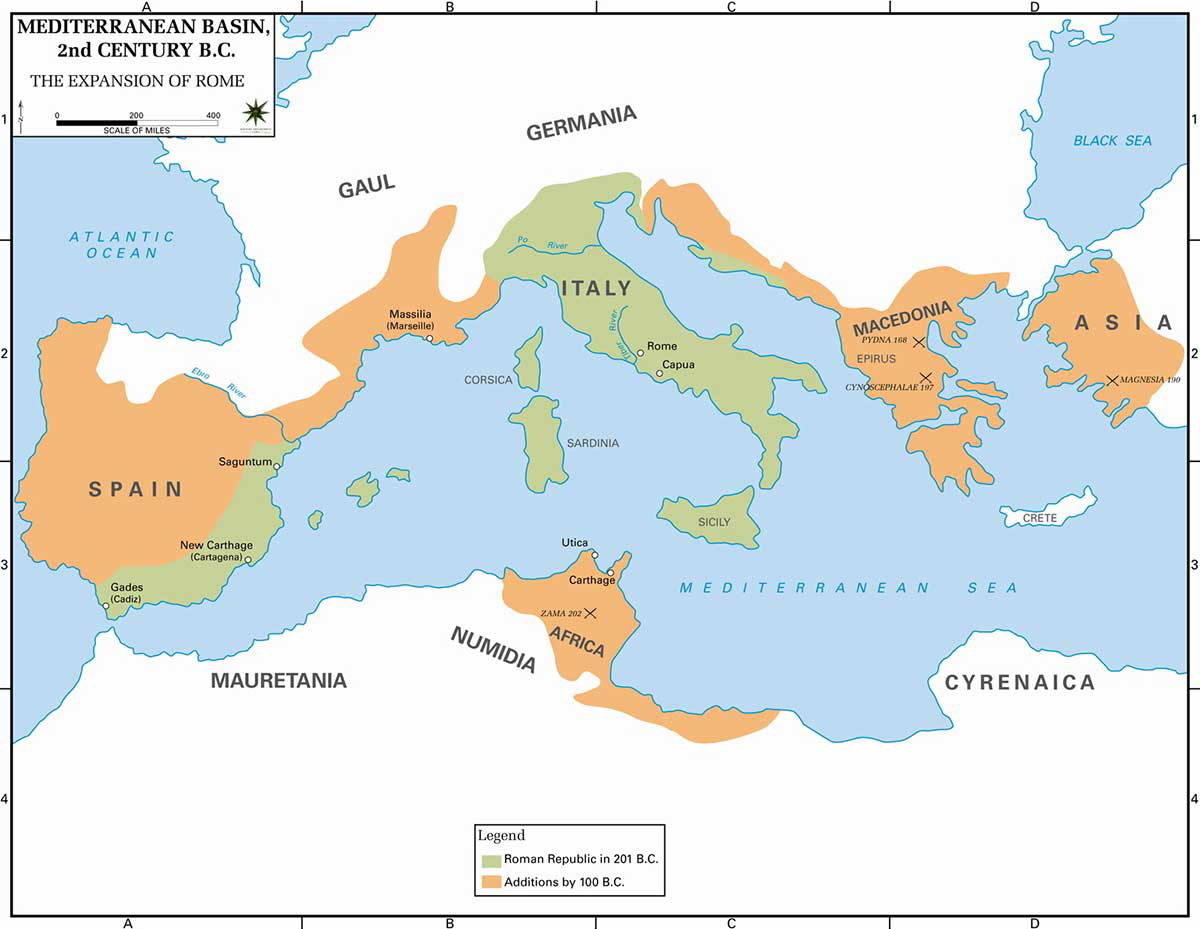

Polybius studied Roman history to develop a theory of government that could explain the rise of Rome. He sought to explain how the Roman Republic came to dominate the known world in only 53 years, from the eve of the Second Punic War in 220 BCE to the end of the Third Macedonian War in 168 BCE. He later extended The Histories to the year 146 BCE. The Histories originally contained 40 books, but only the first five survive in full, along with excerpts of many of the rest.

Who Was Polybius?

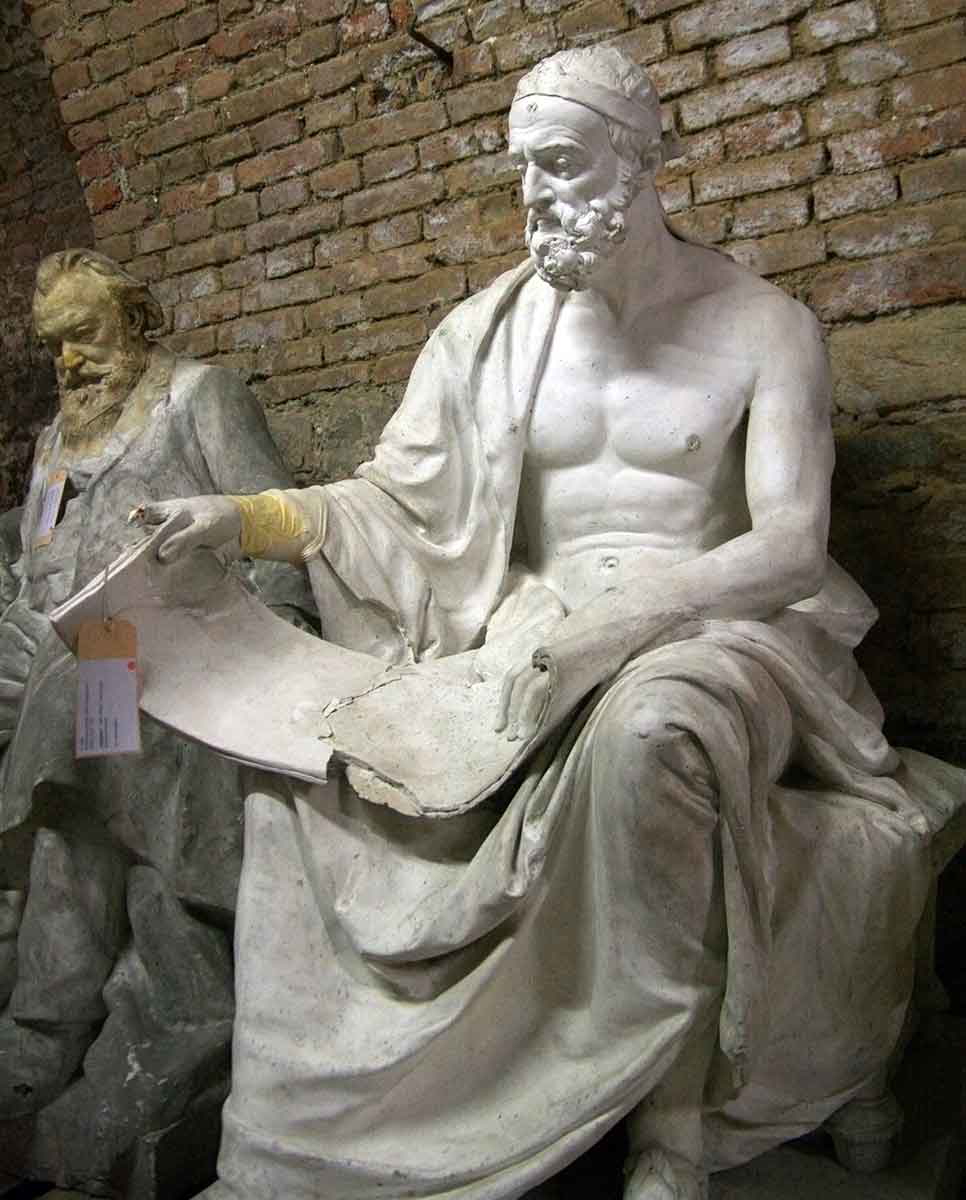

Polybius was born circa 200 BCE in Megalopolis, Greece. He was the son of Lycortas, an important official in a confederation of Greek cities in the Peloponnese known as the Achaean League. Polybius himself later rose to prominence in the league. In 168 BCE, Rome brought the Third Macedonian War to a decisive conclusion by ending Macedonian rule at the Battle of Pydna. Rome then demanded 1,000 hostages from the Achaean League to ensure the league’s compliance with Rome’s new order in Greece. In 168-167 BCE, Rome took Polybius and the other hostages to Italy.

After arriving in Rome Polybius met many of Rome’s elites. He worked under the patronage of the general who had just defeated Macedonia, Lucius Aemilius Paullus. Polybius also befriended and tutored Paullus’s son Scipio Aemilianus. During this time Polybius began to develop his theories of history and government that would form the foundation of The Histories. He also undertook voyages of diplomacy and exploration for his patrons. When Scipio Aemilianus destroyed Carthage in 146 BCE, Polybius was at his side while Scipio wept over the city’s fate.

Who Did Polybius Write For?

Polybius desired to portray the history of Rome and its rise to power in a way that met with the approval of his Roman patrons. This context should be considered when reading The Histories. However, Polybius did not write The Histories solely to please the Romans. In his own words, Polybius stated that his work is a universal history. By universal, he meant that he intended his work to encompass the entire known world. In his view, history was to be considered as a singular whole encompassing all the disparate peoples that inhabited the known world. Polybius placed the history of Rome within this framework, investigating the interactions of the Roman people with these other peoples. Polybius then examined the characteristics of the Roman people to explain the dominant position of Rome that he witnessed in his own lifetime.

Polybius also desired to explain Roman history to his Greek compatriots:

“As neither the former power nor the earlier history of Rome and Carthage is familiar to most of us Greeks, I thought it necessary to prefix this Book and the next to the actual history, in order that no one after becoming engrossed in the narrative proper may find himself at a loss, and ask by what counsel and trusting to what power and resources the Romans embarked on that enterprise which has made them lords over land and sea in our part of the world.” (Polybius, The Histories I.3)

Polybius endeavored to write a history favorable to his Roman patrons, but they were not his only audience. His work was a universal and instructive history for his fellow Greeks, indeed anyone inquisitive enough to ask how the world of his time came to be (Polybius, The Histories I.3).

What Did Polybius Write About?

Polybius developed a theory of systems of government that was rooted in his observations of history. He applied this theory to the Roman constitution to classify exactly what type of government Rome had and how it had allowed Rome to become so successful. In his view, the Roman constitution was a product of natural forces and fortune. Polybius did not simply attribute the rise of Rome to good luck though. For Polybius, “fortune raises up only those who are worthy” (Linderski, 1992, Polybius, para. 1). Polybius believed that the virtues of the Roman constitution ensured that the republic was worthy of the position that fortune had bestowed upon it in the 2nd century BCE.

Polybius attributed Rome’s dominance not only to its political development but to its military prowess as well. Polybius devotes much of Book VI of The Histories to a discussion of Roman military organization, logistics, and methods of encampment. Polybius was especially qualified to discuss military matters. He had risen to the rank of cavalry commander (Hipparchus) in the Achaean League before being taken captive to Rome.

Polybius was equally qualified to expound upon political matters. He was an experienced diplomat and politician. His travels provided him with an extensive knowledge of geography and gave him first-hand knowledge of the peoples and places he wrote about. He was also well-read in literature, philosophy, and the works of the historians that preceded him. For these reasons, his theory of systems of government in Book VI is possibly the most well-known part of The Histories.

Polybius and the Types of Government

Chapter four of Book VI of The Histories is often titled Systems of Government or the Rotation of Polities in English translations. This chapter is much more than just a simple catalog of the types of government that had arisen throughout the known world. Polybius defines the types of government that have existed throughout history and relates them through a natural progression as one type evolves into the next in a continuous cycle.

Polybius starts by listing three basic types of government: kingship, aristocracy, and democracy. Polybius was clearly influenced by Aristotle (see Politics Book V), who in turn had been influenced by Plato. Polybius goes a step further however and declares that there are in fact six types of government, organized into three pairs: kingship and tyranny, aristocracy and oligarchy, and democracy and mob rule. The first member of each pair is the original and good form of its respective type of government while the second member of each pair is its congenital and degenerate counterpart.

Polybius believed that kingship arose naturally from a society’s need for government. Kingship eventually degenerated into tyranny. Tyranny gave way to aristocracy—rule by a select group of the wisest and ablest men who would arise to end the depredations of tyranny. Aristocracy then became perverted into oligarchy. Polybius believed that the people would then rise up to avenge the unjust acts of the oligarchs and form a democracy. Over time democracy would then degenerate into mob rule. A strong leader would then emerge to put an end to the chaos, becoming king and starting the cycle over again.

Polybius and the Roman Constitution

Polybius characterized the Roman constitution as a mixed form of government. It contained aspects of each of his three basic types: kingship, aristocracy, and democracy. In his view, this was its chief virtue, for no one aspect of the constitution could become preeminent and each part depended on the others to carry out its functions. In other words, Rome’s mixed constitution provided a system of checks and balances. This meant that Rome had the best form of government in the known world, which is why it had achieved dominion over it.

According to Polybius, the consuls represented the kingship aspect of the Roman constitution. Their authority over all other government offices (with some limitations imposed by the veto power of the tribunes) and their almost unlimited military authority gave them powers similar to kings. The Senate represented the aristocracy. This body of elites had control over the treasury, public buildings, and foreign policy. The powers not held by the consuls or the Senate were left to the people, who represented democracy. Their powers included deciding rewards and punishments for officeholders, rendering verdicts for capital charges, and approving legislation, treaties, and declarations of war.

This description of the Roman constitution would have been agreeable to the Roman mindset. Polybius argued that the rotation of polities was a natural course of events, exemplified more clearly by Rome than any other state. In the eyes of his Roman audience, Polybius legitimized the Roman system of government by portraying it as the product of natural causes, destined to arise, destined to rule. In addition, the Romans would have keenly observed that the kingship-tyranny form as described by Polybius had indeed arisen early in Rome’s history and was then subsequently overthrown.

Polybius as a Historian

Modern historians occasionally criticize Polybius for being too overly reliant on Aristotle’s political model and on Greek philosophy in general. Modern historians also sometimes argue that Polybius had too simplistic an understanding of the organs of Roman government. However, Polybius explicitly states that he deliberately omitted certain details of the Roman constitution that he felt were not important to his account. Additionally, the fact that much of The Histories is no longer extant, including portions of Book VI, presents some difficulties in criticizing Polybius on this point. In any case, there is little debate that Polybius made several important innovations in the practice of political history. He expanded on and clarified the categories of government. He applied his theories to a concrete example in the form of the Roman constitution rather than leaving them as abstractions.

Despite these criticisms and despite his clear admiration for the Roman constitution, historians do not dismiss The Histories as mere Roman propaganda. Polybius is generally regarded as a careful and rational scholar who strove for accuracy and detail. Rather than write simple narratives, he explained the purpose of writing history, investigated causes and effects, and elucidated the principles of statecraft. Perhaps even more significantly, an empirical study of the history of the Roman Republic confirms the accuracy of many of his observations.

Bibliography

Aristotle, Politics

Bury, J. B. (2006), The ancient Greek historians. Barnes and Noble Publishing, (Original work published 1909)

Linderski, J. (1992), Polybius, In Academic American Encyclopedia, Grolier

Plato, Republic

Polybius, The histories

Walbank, F. W. (1964), Polybius and the Roman state. Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies, 5(4), 239-260, https://grbs.library.duke.edu/index.php/grbs/article/view/11811