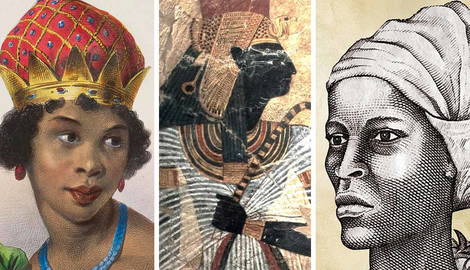

The history of black women is exciting and contentious, yet we rarely hear about independent black women in positions of power forced to make difficult decisions on behalf of their people. This is a symptom of history, which has traditionally played down the stories of women, especially black women, more often casting them as supporting characters or extras. While this article will not remedy centuries of neglect, you will discover the compelling stories of four black queens who have shaped history.

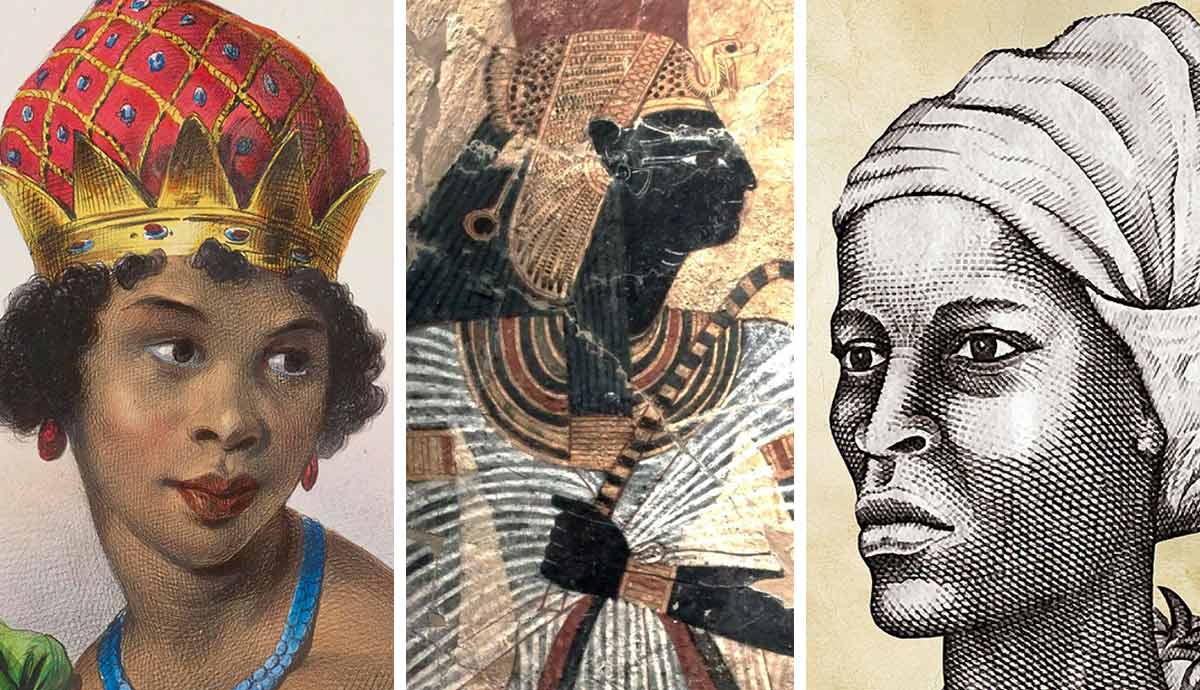

Queen Ahmose Nefertari of Egypt (c. 1570-1505 BCE)

Born around 1570 BCE to Seqenenre Tao, the last pharaoh of the 17th dynasty, and his sister-wife Ahhotep I, Ahmose Nefertari also married her brother, Ahmose I, becoming the first Great Royal Wife of the 18th dynasty. Ahmose I expelled the Hyksos from Egypt after years of struggle to reassert native Egyptian rule. The pharaoh united Upper and Lower Egypt under a Theban monarchy, which made him and his chief wife famous for centuries to come.

The debate surrounding whether ancient Egyptians were black continues, but Ahmose Nefertari is nearly always depicted in reliefs with very dark skin. Experts have proposed that Ahmose Nefertari was of Nubian origin, as they were typically depicted with darker skin. She was the first Egyptian queen to be declared the wife of the god Amun, which made her powerful within the already powerful Theban priesthood, and she was given the title Divine Adooratrix. Amun was also typically depicted as black, offering another explanation for Ahmose Nefertari’s depictions. This all suggests she had important oversight of temple administration, staff, and treasuries.

Historians point to inscriptions indicating that the queen led construction projects. Ahmose Nefertari’s name is mentioned in records documenting the opening of limestone quarries and appears inscribed on the walls of an alabaster quarry near Assiut. In another instance, Ahmose I noted that before initiating the construction of a cenotaph in honor of his grandmother Tetisheri, he sought the approval of his wife.

When Ahmose I died, Ahmose Nefertari served as Queen Regent for their young son, Amenhotep I. It has been suggested that during this period, she set up the famous Valley of the Kings and was a patron of Deir el-Medina, the residence of the temple artisans. Furthermore, Ahmose Nefertari survived her son and was alive for the coronation of her grandson, Thutmose I.

Thutmose I (or perhaps his advisors) had a large statue of his grandmother set up at Karnak before she died in around 1505 BCE. Upon her death, the people of Deir el-Medina initiated a memorial day for her. The late queen was deified with the epithet “Mistress of the Sky,” which illustrated the impact Ahmose Nefertari had on the subjects of Egypt. She continues to be revered centuries after her death and was even depicted in temples during the Ramesside dynasty.

Queen Amina of Zazzau (c. 1533-1610 CE)

Amina was born sometime in 1533 in present-day North West Nigeria in the kingdom of Zazzau, today the city of Zaria. Oral tradition records that she was brought up and favored by her grandfather, King Sarkin Nohir, who taught her politics from a young age. He even attended a formal, national meeting with young Amina on his lap. In another story, when Amina was still a child, she was found practicing with a dagger by her grandmother, Queen Marka. From then on, Amina trained in warfare as well as typical feminine duties. As she grew older, she was instructed in leading military forces and trained with the royal guard.

King Nikatau and Queen Bakwa Turunku, Amina’s parents, assumed the throne of Zazzau when Amina was around 16. Despite having a younger brother, Amina was named Magajiya, or the heir apparent. As Magajiya, Amina was given 40 female slaves. Suitors pursued the princess relentlessly, with one Emir (local chieftain) offering her 50 male slaves, 50 female slaves, and copious amounts of cloth. Yet, Amina declined all offers, and there is no mention of any family pressure on her to marry.

Legend says that when Amina was little older than 16, she led Zazzau’s cavalry into battle against an invading city-state. The approaching army scoffed at the idea of a young woman at the helm of Zazzau’s forces, but they swiftly stopped as Amina and her troops navigated the battlefield with ease. Her fame as a warrior was cemented through her first military victory.

In 1566, King Nikatau died, but Amina did not succeed him. Instead, her brother Karama was crowned king. However, Amina remained at the forefront of the royal family as a fearsome fighter and led multiple Zazzau triumphs. But just ten years after he assumed the throne, Karama died. The throne passed to Amina. Only three months into her reign, Amina began expanding her kingdom’s borders and continued leading the army personally. The state army was 21,000 men strong, and Amina led them north and south of Zazzau, conquering cities as she went.

Consequently, Zazzau dominated trade routes from modern Nigeria through to Sudan and Egypt. Furthermore, she built walls around defeated cities and established military command posts and enslaved much of the male population. Interestingly, the legend also suggests that she took a lover in each city, but executed him soon after.

Amina was the sole ruler of Zazzau for 34 years and died childless in battle near Altagara at the impressive age of 77. Today in Nigeria, she is often given the epithet “Amina, rana de Yar Bakwa ta San,” which means Amina, daughter of Nikatau, a woman as capable as a man.

Queen Nzinga of Ndongo and Matamba (c. 1583-1663 CE)

Similar to Queen Amina, Nzinga Ana de Sousa Mbande was raised in the royal court of her grandfather, King Ngola Kilombo Kia Kasenda of Ndongo. Her father ascended the throne when Nzinga was ten, and he showed Nzinga special favor despite her being the daughter of a concubine. This fact benefited Nzinga greatly as she was not in competition with her father’s legitimate heirs, so the king could lavish her with gifts and attention. She had a traumatic birth, with the umbilical cord wrapped around her neck. Royal children who survived difficult or unusual births were often believed to possess spiritual gifts, with their survival as a sign that they would grow into powerful and proud individuals.

Nzinga underwent military training and was prepared to accompany her father in combat, demonstrating notable proficiency with the battle axe, the customary weapon of Ndongan warriors. In addition to her martial education, she actively participated in various official and administrative functions alongside her father, including legal proceedings, military councils, and significant ceremonial rituals.

One key difference in Nzinga and Amina’s early lives, however, was the turmoil caused by European colonialism, in the case of Ndongo, that of Portugal, so Nzinga learned Portuguese from a young age. The Portuguese Empire came to Ndongo in 1575. Despite peace for nearly a decade, the relationship became tense. Soon after, significant portions of Ndongo came under Portuguese control. The Portuguese conducted their military campaigns with considerable brutality; alongside their territorial expansion, they also captured large numbers of individuals to be sold into slavery.

The conflict greatly undermined the authority of the Ndongan monarchy, as numerous noblemen, or sobas, withheld tribute from the crown, and some even aligned themselves with the Portuguese. By the time Nzinga’s father ascended to the throne in 1593, the region had been severely destabilized. In 1617, Nzinga’s father died, and her brother Mbandi succeeded him as king. Paranoid, Mbandi had many potential heirs executed, including Nzinga’s young son. Furthermore, Mbandi forced his sisters to have hysterectomies so that he would face no future competition for the throne.

By 1621, Nzinga had been recruited by her brother to be the Ndongan ambassador and liaise with the Portuguese in Luanda (Angola). Nzinga immediately broke conventions by wearing traditional Ndongan dress at a time when African diplomats typically wore European dress. While the Portuguese were undoubtedly captivated by Nzinga, they took steps to portray subjugated peoples as lesser. When Nzinga arrived to negotiate with the Portuguese, seating had been arranged exclusively for the Portuguese officials, while she was offered only a mat. As a result, one of Nzingha’s attendants positioned himself to serve as her seat, enabling her to address the governor on equal footing. Nzinga proposed peace by allowing slave traders access to Ndongo. In return, Nzinga pressured the Portuguese to demolish any bases they had set up on Ndongan land and dictated that Ndongo would not pay tribute, as they had not been conquered. To demonstrate her commitment to peace, Nzinga shocked the Portuguese by agreeing to be baptized. She assumed the name Ana de Sousa in tribute to the Portuguese governors, and the treaty was signed.

After tensions escalated with the neighboring Imbangala, the Ndongan royal family was forced to flee their court in Kabasa. A year later, King Mbandi recaptured Kabasa and cautiously explored Christianity to appease the Portuguese. Nzinga advised him against baptism, arguing it would alienate traditionalist allies. Meanwhile, the Portuguese violated the treaty by maintaining forts and launching raids into Ndongo. By 1624, Mbandi had fallen into a deep depression and delegated much of his authority to Nzinga.

In the same year, King Mbandi died under contentious circumstances. Nzinga was selected as successor but had to fight off many potential male heirs. Perhaps in an act of retribution, Nzinga had Mbandi’s son, who was only seven years old, put to death. To fully consolidate her position, Nzinga married Kasa, an Imbangala chief.

Although Nzinga was originally happy to allow the continuation of the slave trade, she now wanted to undermine the Portuguese authority by advocating for enslaved Ndongan people to escape Portuguese settlements, leading to war in 1626. Nzinga was initially defeated and forced to retreat while the Portuguese rounded up more slaves. In 1627, Nzinga sent a peace envoy to the Portuguese, declaring that she would pay tribute if the Portuguese supported her claim to the throne, as some Ndongan nobles resented a woman in charge. The Portuguese replied by executing the delegate. Again seeking allies, she married another powerful Imbangalan chief, fully integrated herself into the culture, and prepared her new army for war.

First, Nzinga invaded and conquered the Kingdom of Matamba, overthrowing Queen Mwongo by 1635. She then settled exiled Ndongans in the region, establishing Matamba as her base for efforts to reclaim Ndongo. With its cultural acceptance of female leadership, Matamba provided a more stable foundation. Nzinga expanded the slave trade to finance her military campaigns and divert wealth away from the Portuguese. Nzinga created an all-female bodyguard for her personal protection and required her male concubines to dress in women’s clothing and refer to her as king.

As her wars with the Portuguese continued, Nzinga forged alliances with neighboring kingdoms and used her army to influence regional succession disputes. She died in 1663 at the age of 80 or 81, leaving a lasting legacy as a bold warrior, shrewd diplomat, and determined defender of her people’s independence.

Queen Nanny of the Maroons (c. 1686-1760 CE)

While Nanny of the Maroons may not have been genuine royalty, she was given the epithet Queen Nanny due to her successful leadership of the Maroons in Jamaica. In 1655, the British Empire captured Jamaica, ousting Spanish colonialists active since 1509. In the brief period of confusion, many enslaved African people made a break for the mountainous terrain that was uninhabited by the colonists and joined the increasing population of Maroons. The Maroons were individuals of African descent who escaped enslavement in the Americas and established autonomous communities, frequently in remote or inaccessible regions such as mountains, swamps, and jungles. These conditions provided the Maroons a tactical advantage against the aggressors who otherwise would have held an uncontested upper hand due to weaponry, military experience, and sheer numbers.

Oral tradition suggests that Nanny was the daughter of an African prince who was deceived by the Spanish and sold into slavery. Alternatively, it has been proposed that Nanny was born into the Maroon community around 1686 in the Blue Mountains of Jamaica with familial ties to the Akan people of present-day Ghana. More accounts indicate that Nanny was perhaps a runaway slave who broke free from a Spanish plantation when the British invaded Jamaica. Other traditions implied Nanny was a slave from West Africa who, upon arrival in Jamaica, made a daring escape before her ship had even docked.

Nanny emerged as the leader of the eastern Maroon community, named the Windward Maroons, while Cudjoe and Accompong led the Maroons in the West. The First Maroon War represented a sustained resistance movement against British colonial forces between 1728 and 1739. Under Nanny’s command, the Windward Maroons engaged in a highly effective campaign of guerrilla warfare that significantly disrupted British control. Under Nanny’s leadership, the Windward Maroons essentially destabilized plantation economies and exposed the structural weaknesses of colonial governance.

The Windward Maroons capitalized on their intimate understanding of Jamaica’s landscape to carry out tactical ambushes, swift raids, and unexpected offensives. They also employed psychological tactics, fostering a legendary status that unsettled British troops. Contemporary reports describe eerie illusions such as trees appearing to move, reflecting the Maroons’ exceptional use of concealment and environmental manipulation. The British tried to seize a Maroon settlement called Nanny Town on numerous occasions but were unsuccessful. During the course of war, the Windward Maroons were able to free around 1,000 enslaved people.

By 1740, the British had run out of ideas and seemingly ran out of hope in their quest to crush the Maroon rebels. A treaty gave the Maroons 500 acres of Portland Parish, where they could govern themselves and engage in social, economic, and cultural independence freely. But the treaty came with concessions. Most notably, the existing Maroons were forced to agree to no longer offer refuge for runaway slaves. By doing so, the British nullified the greatest threat to their economic stability. The freedom of a limited number of once enslaved Africans was a small price to pay.

This placed the Maroons in a difficult position. Once the voice of a firm rebellion against slavery and colonialism, the Maroons were now complicit with the oppressive system that they had fought for over a decade. Queen Nanny herself did not orchestrate the signing of the treaty, but it is said that she supported it.

Although Queen Nanny is most notable for her prowess on the battlefield and sophisticated military tactics, she was also celebrated for her devotion to African spiritualism. Specifically, she was known to practice Obeah, a tradition originally from West Africa that evolved through the incorporation of other customs and folklore from the African diaspora and native Caribbean populations.

This meant that Queen Nanny was a military, political, and spiritual leader. She played a crucial role in the newly independent Maroon communities by establishing systems of trade, cultivation of the land, and an economic system that allowed them to be self-sufficient.