The Queen of Sheba was the ultimate “it girl” of antiquity, with “it” being everything—unmatched wealth, political power, and an air of mystery that still makes historians swoon. When she rolled into Jerusalem to meet King Solomon, the wisest king of Israel, it was a moment dripping with grandeur and, one imagines, chemistry. Their legendary rendezvous, filled with riddles, riches, and maybe a touch of flirtation, has been celebrated for centuries. Here’s the glaring plot hole: we have no idea if it actually happened. The confab of these two forces is part myth, part history, and entirely iconic. This story has inspired everything from sacred texts to some seriously breathtaking artwork.

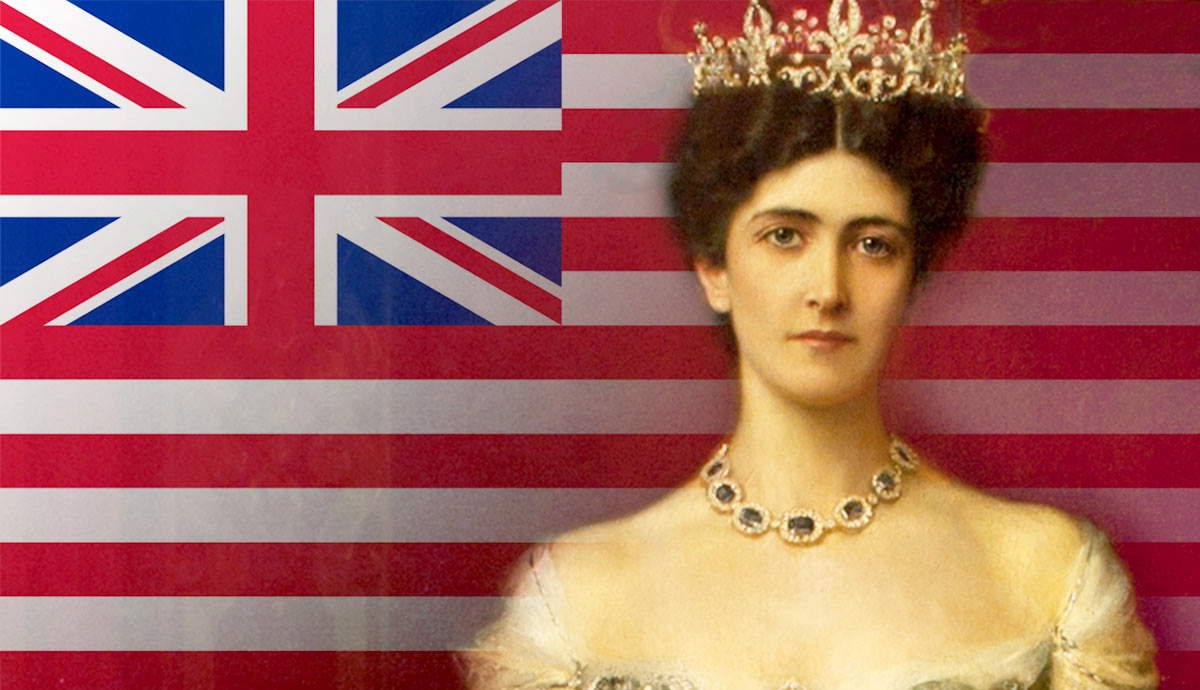

1. Poynter’s Visit of the Queen of Sheba (1881-1890)

Poynter’s The Visit of the Queen of Sheba isn’t just a love letter to this myth of antiquity—it is a full-blown sonnet to the Victorian vision of feminine grace. Women weren’t just people—they were muses, symbols, and paragons of beauty, domesticity, and moral fortitude. The Queen of Sheba, with her legendary wisdom and the treasures of her kingdom, was the perfect canvas for this kind of idealization.

The end of the 19th century was an all-you-can-eat buffet of artistic styles, each more distinct and ambitious than the last. Romanticism gave us drama and emotional intensity; Realism brought us back down to earth with its gritty depictions of everyday life. Symbolism whispered attention-grabbing shapes and the creations of the subconscious, while Neoclassicism resurrected ancient Rome with all the marble bulging muscles and draped togas one could want. That’s not to forget Impressionism, which traded hard edges for a haze of light and movement, or Art Nouveau, the art world’s floral, sinuous love letter to nature’s ornamentation.

Nestled in this kaleidoscope of creativity was the Olympian School of Art, a group of painters who turned up the longing for the perfection of a world gone by to eleven. These artists—think Sir Edward John Poynter, Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Lord Frederic Leighton, and George Frederic Watts—specialized in high-drama historical scenes that made any onlooker wish themselves back to an idealized Greece. However, it was an ancient Greece with a Victorian twist. The Elgin Marbles, a collection of classical Greek sculptures newly arrived in London in 1807, were a major inspiration to this collective of artists.

Take a close look at Poynter’s queen: she’s regal, poised, and wrapped in an aura of glowing self-awareness. She’s not just a queen—she’s the Queen, embodying a cocktail of power and delicacy that Victorian audiences found irresistible. Don’t let the monarch’s crown distract the eyes—this depiction isn’t about political clout or even historical accuracy. It is about embodying the virtues Victorian society wanted in its women: elegance, tutored poise, and just a whisper of exotic allure to keep things from getting too bland.

The architectural fantasy of Solomon’s temple, with its rich crimson columns and grand staircase, mirrors the way Poynter constructs his queen. Every bead, every fold of fabric, every calculated gesture is designed to evoke a sense of perfection that’s heartbreaking in its impossibility. This lithe Queen isn’t just an individual, she’s an archetype, a dream of what women should aspire to be. She’s the Victorian world’s “Next Top Model,” easily.

Therein lies the rub. By elevating his beautiful queen to such dizzying heights, Poynter reveals more about his era’s anxieties and aspirations than he does about the biblical Queen of Sheba herself. In a century grappling with industrial chaos and shifting gender roles, this moving vision of the Queen of Sheba offered a comforting, controlled ideal. She’s beautiful, wise, and powerful—but only within the confines of the gilded frame Poynter has built for her. It’s a vision as lavish and unreal as the temple she stands in, but one that still manages to dazzle and entice.

2. Rubens’s King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba (1620)

Peter Paul Rubens didn’t do understated, and his Queen of Sheba fits right into his wheelhouse. Rubens didn’t just depict life—he performed on canvas. His works feel rich and full, every open space is used to build a more elaborate scene. His very name has become synonymous with a love for the human form that goes beyond mere representation. Thus King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba (1620) fit with this signature motif. The Queen doesn’t just visit Solomon—she arrives, commanding the scene with an unapologetic golden glow as if her silks and skin exude her fabulousness.

The Queen of Sheba, as Rubens presents her, is no waif (none of his painted female figures are, really). She is not fragile but commanding, and undeniably regal. Her physique, rendered with the lush, fleshy vitality for which Rubens is most known, embodies the Baroque aesthetic: theatrical, indulgent, and unapologetically luxurious. This wasn’t just an artistic choice; it was a statement. In Rubens’s time, a fuller figure symbolized wealth, fertility, and status. If you had a bit of softness around the edges, you weren’t just eating fine food—you were thriving.

Rubens’s approach to portraying women wasn’t merely about celebrating curves. His female figures—whether they were goddesses, queens, or mythological heroines—carried an aura of stoutheartedness and agency. The Queen of Sheba in this painting isn’t a passive ornament in Solomon’s court. She’s a powerful woman meeting an equally powerful man, and the magnetism of their exchange is easy for an audience to read.

Rubens’s male figures, by contrast, exude physical power, reflecting the artist’s fascination with Greco-Roman ideals of masculine strength. Despite this, Rubens didn’t apply these old-world standards to women. He understood that femininity, in all its forms, could also convey influence—just not in the same sculpted, Herculean way. Instead, his women are dynamic, sensual, and unafraid to take up space, even in the most glorious of settings.

In King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, Rubens’s indulgent style mirrors the opulence of the biblical narrative. The Queen’s richness of form and presence isn’t a negative commentary but a celebration of abundance, femininity, and the success of the country she runs, which is bountiful and affluent. It is a testament to Rubens’s ability to blend the sensual with the sublime, turning his medium into a feast for the senses.

Rubens was heavily inspired by the Venetian masters—think Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese—and his work here reflects that same theatrical, palatial feeling. The Queen of Sheba doesn’t merely bask in Solomon’s presence: she herself commands a spotlight, forcing those around her to notice.

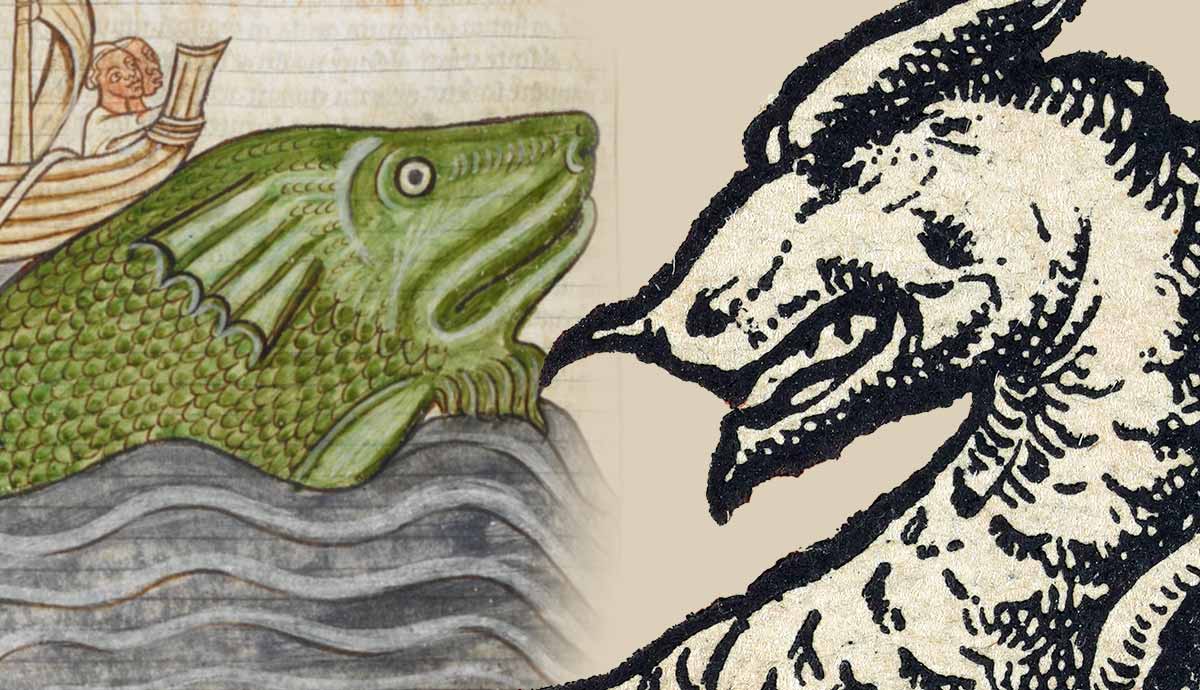

3. The Queen of Sheba in the Bellifortis Manuscript (ca. 1405)

There exists a medieval depiction of the queen in Konrad Kyeser’s Bellifortis, a military treatise with an unexpected addition of the mystical. She’s royally done up in an ermine-lined gown, a scepter, and bearing the globus cruciger (that orb-with-a-cross symbol of authority). She appears to be dark of complexion but this is no longer thought to be the original depiction—her face and hands were darkened by a later artist to signal “exotic” origins.

Konrad Kyeser’s Bellifortis (ca. 1405) is not your average treatise. Imagine a mash-up of martial engineering, astrology, and somewhat eccentric miscellanea. To make it special, all this was packed into nearly 180 illustrations that beautifully illuminate the pages. Think of this artwork like the Pinterest board of a 15th-century war strategist with a flair for the dramatic—and tucked within its pages is a curious but lovely depiction of the Queen of Sheba.

Why does the Queen of Sheba show up in a manual about trebuchets and fortifications? At first glance, her presence might seem as out of place as a sauna in a war manual (which is also in there). Odd as it may seem, Kyeser’s inclusion of Sheba aligns with the manuscript’s penchant for blending the practical with the enchanted.

This depiction highlights her association with technological marvels and transport, a nod to her legendary journey to meet King Solomon. Let’s not ignore the medieval gaze here: Sheba’s portrayal also reflects Kyeser’s fascination with blending historical and mythical figures into his war-focused tableau. Her presence humanizes the text, adding a narrative thread to what might otherwise be a dry inventory of gadgets and weaponry.

This manuscript is a testament to the late-medieval obsession with cataloging knowledge, no matter how, let’s say, wide-ranging. In Sheba, we see a queen who transcends her biblical origins to become a symbol of ingenuity and cultural exchange. Was she included because Kyeser thought her story added gravitas to his treatise or was he indulging in a bit of medieval fanfic? Either way, Sheba’s cameo in Bellifortis reminds us that the boundaries between myth, history, and technology were as fluid then as Kyeser’s interests were expansive.

4. Charles Gleyre’s The Queen of Sheba (1838)

For a painter who taught Impressionist goliaths like Monet and Renoir, Gleyre himself leaned more toward tradition and formal technique. His Queen of Sheba is drenched in wealth and elegance, though the colors he chose are rather shadowy and create a moody setting for her vaunted arrival. The towering giraffes that pull her retinue forward can barely be made out; are they giraffes from a foreign land or strange creatures too curious to name?

Gleyre’s style was shaped by his training and travels. He studied in Paris under Louis Hersent and later absorbed the classical traditions of the École des Beaux-Arts. However, it was his extended stays in Italy and the Near East that most influenced his works to come after. Gleyre was deeply influenced by the luminous colors and atmospheric effects he encountered abroad, particularly in Egypt, which likely informed the genteel yet restrained setting of The Queen of Sheba.

While Gleyre’s work often leaned toward the academic style of the French Salon, his Sheba reveals an artist willing to experiment with tone and shading. The painting eschews bombast in favor of an illusory elegance that invites viewers to reflect on the queen’s character rather than her wealth. In doing so, Gleyre’s Sheba bridges the gap between an idealized mythic queen and the very real human variability of emotions, offering a nuanced take on a story that has often been told in strokes of gold and evocations of male and female perfection.

With its moody lighting and velvety textures, this work serves as a love letter to a bygone era (albeit through a distinctly Colonial lens). Gleyre’s Sheba is theatrical, even if it is not a feast for the eyes the way so many portraits of this conclave of titans are.

5. Sheba on the Portal of St. Anne, Notre Dame, Paris (1200)

Even Gothic architecture couldn’t resist the queen’s allure. On the St. Anne portal of Notre Dame, Saba’s queen makes a cameo among a cast of Old Testament luminaries. Originally sculpted around 1200, her statue was later renewed during Viollet-le-Duc’s controversial 19th-century restoration.

The sculptors of the Portal of St. Anne worked in a transitional moment between Romanesque solidity and Gothic lightness. Sheba’s form retains some of the rigidity of earlier Romanesque depictions, yet her expression and posture murmur the individuality that would come to define Gothic art, with a very Mona Lisa-like hint of a smile. Her sculpted clothing is textured, her fingers long like a pianist’s. She is stone, but there is a movement to her that seems engaging. At the same time, her presence there reinforces the Gothic cathedral’s broader narrative purpose—to present a unified vision of salvation history, where even faraway queens find their place in the divine story and are carved into stone to honor their role therein.

Her inclusion on Notre Dame’s portal underscores a medieval fascination with the Queen of Sheba as a stand-in for the new concept (at least in Western culture’s living memory) of successful queens regnant.

The Queen of Sheba’s dignified perch on the Portal of St. Anne at Notre Dame isn’t just a nod to biblical storytelling—it is a quiet but compelling piece of social commentary in a time when queens across Europe were beginning to rule in their own right. Think of Sheba as both a symbol of feminine insight and an aspirational mirror for women of power navigating the choppy political waters of the 12th and 13th centuries. This statue was a Gloriana before her time, though one that didn’t just go on progressing to her many holdings within her own land. This statue depicted a forerunner of Good Queen Bess who was willing to travel widely and fearlessly with her fortune.

In medieval Europe, the idea of women in leadership was still a spicy topic. Eleanor of Aquitaine was stirring up male tempers by asserting her authority by right as a duchess and queen, and Empress Matilda had fought tooth and nail to claim, though she never really held, the English throne just a few decades earlier. While Sheba isn’t written as a sovereign wielding outright political power in her biblical narrative, her journey to Solomon is all about intellectual agency. She’s not there for romance or conquest—she’s there to test Solomon’s famed wisdom and trade on her own terms.