Théodore Géricault was one of the most famous artists of Romanticism. In 1818, he painted a dramatic scene that was still fresh in his contemporaries’ minds—the shipwreck of the frigate Medusa and the makeshift raft on which part of the crew desperately tried to swim to safety. Exhausted and mentally unstable, the survivors resorted to violence and cannibalism. Géricault’s painting made a sensation in the art world and influenced generations of artists. Read on to learn more about Théodore Géricault’s masterpiece.

The Raft of the Medusa: The Tragedy That Inspired Géricault

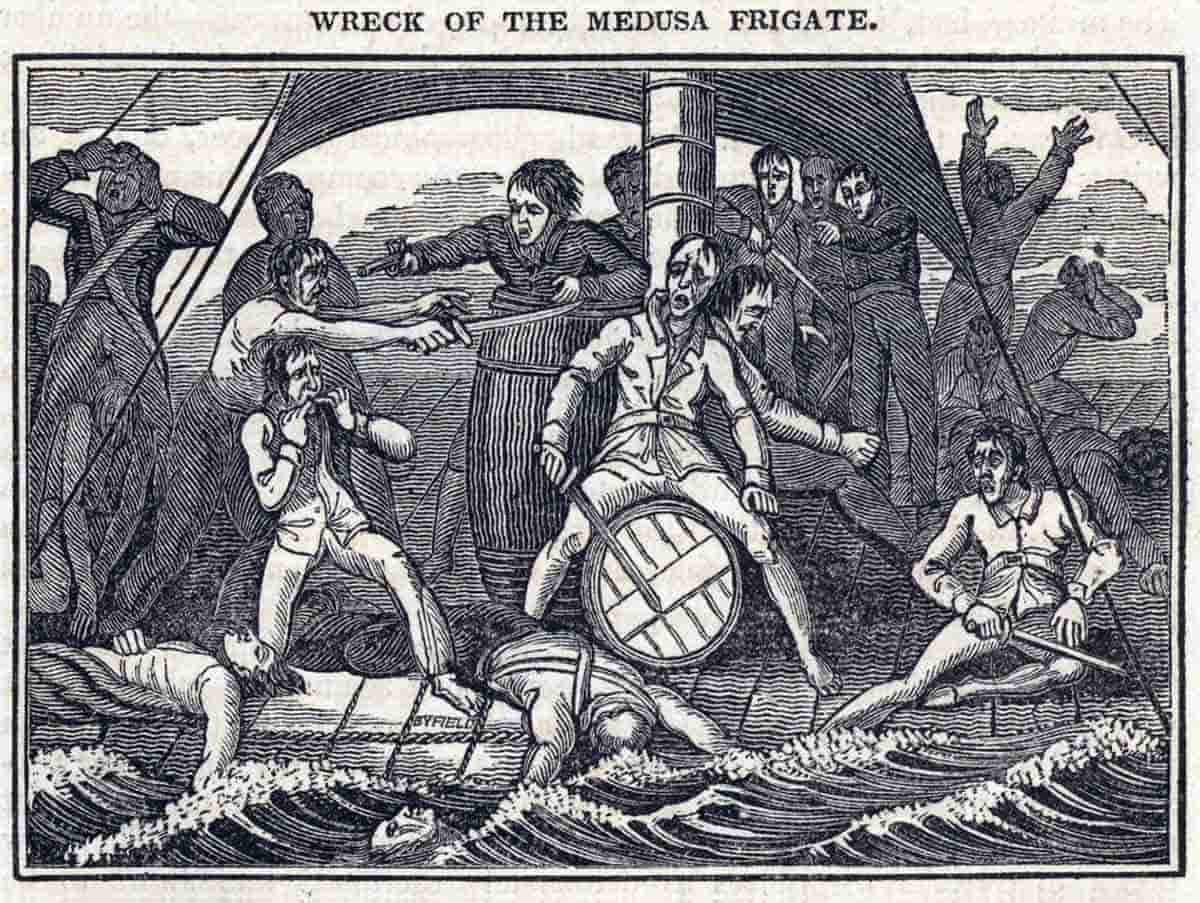

The story of one of the most controversial paintings of all time began in 1816, when the French frigate Medusa, under the command of Hugues Duroy de Chaumareys, sailed towards Senegal. France recently received part of its African colonies back after the Napoleonic wars and sent a convoy of ships led by Medusa to re-colonize the land. The captain’s competence quickly raised concerns about the passengers since Chaumareys lost contact with the rest of the convoy and appointed a random passenger as his navigator. The inexperienced navigator failed to calculate the course correctly, and on July 2nd, 1816, Medusa ran into shallow waters.

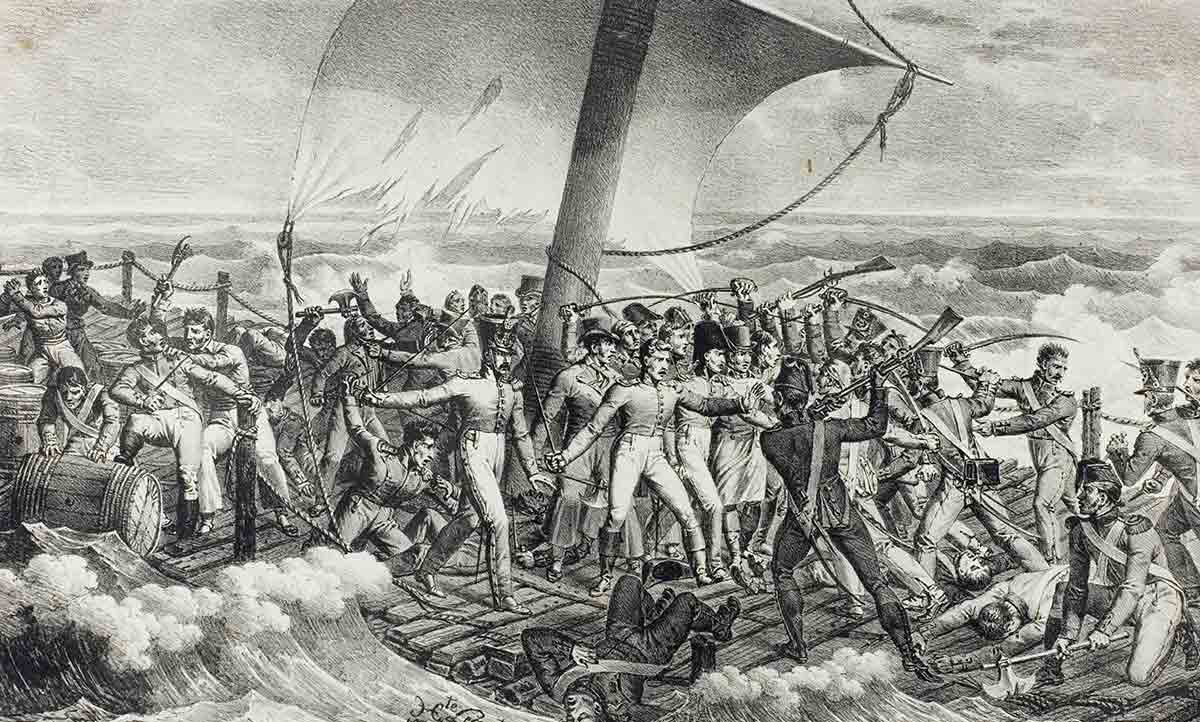

The captain ordered the evacuation, but the number of lifeboats on the Medusa was insufficient for the amount of people on board. Officers and crew members occupied lifeboats, leaving the remaining 150 people behind. Among them were groups of ordinary men and women who intended to settle in Senegal, as well as low-rank sailors and soldiers. In a desperate attempt to save their lives, they made a makeshift raft big enough to fit all of them. Initially, the raft was tied and pulled by several lifeboats, but upon noticing an approaching storm, the captain ordered the rope to be cut, leaving the raft to drift on its own.

The raft had a very limited and rather odd amount of supplies: not enough water but plenty of wine and almost no food. Alcohol made the situation even worse, as drunk sailors started to fight for places closer to the center in order to avoid being dragged into the water by waves. They also tried to overturn the authority of the remaining officers. Violence and the lack of drinking water soon took effect, with the raft’s population rapidly decreasing.

No special efforts were made to rescue the drifting raft. On July 17th, the brig Argus, searching for the remains of Medusa’s cargo and gold, accidentally discovered the raft. Out of 150 people who boarded in, only 15 were left. A few days before the discovery, they agreed to push everyone who was injured, sick, or insane off the raft. They also threw away the remaining weapons to avoid more violence. By then, desperate people had already resorted to cannibalism and drinking their own urine to stay hydrated.

Soon after the rescue, most of the survivors died from exhaustion. One of the lucky ones was the surgeon Henri Savigny, who managed to write a detailed report about Medusa’s wreck and the events that unfolded on the raft. He highlighted the crucial role of Medusa’s captain Chaumareys in both faulty navigation and abandoning the raft. Chaumareys was an incompetent officer who secured his position not through actual experience but due to his politically favorable views: he was a well-known, staunch supporter of the monarchy, a trait crucial to French governmental institutions still recovering after the Revolution. Chaumareys faced the prospect of the death penalty, but his loyalty to the crown saved him. He was quietly sentenced to three years in prison. Afterward, he retired, in debt, and abandoned by all his ex-colleagues.

The crash of the Medusa and its raft represented more than a tragic but not uncommon shipwreck. It represented the crisis of the French state, where the ruling classes lost all authority. Incompetent captains received their titles because of their political reliability rather than actual qualification, and respectable gentlemen easily turned into murderers and cannibals when left unattended.

Painting “The Raft of the Medusa”

At the time of the Medusa catastrophe, Théodore Géricault was studying painting in Rome. He was desperately looking for a subject dramatic enough to turn into a masterpiece, reading ancient myths and French criminal chronicles. When he discovered Henri Savigny’s report, published as a book, he knew that the search was over. To focus on his work, he stocked art supplies, locked himself in his studio, and shaved his head to avoid the temptation of going out.

Géricault needed time to come up with the definitive composition of The Raft of the Medusa. For a while, he was looking for a precise moment of the tragedy to turn into a painting. He started with the most shocking parts—scenes of cannibalism and drunken fights. However, he soon decided that these scenes were too sensationalist and would turn the dramatic composition into a gory attraction.

Instead, he chose to show the decisive moment in the raft’s story: the second when the few remaining survivors noticed the silhouette of the brig Argus on the horizon. Exhausted, starving, and deeply traumatized, they felt a glimpse of hope, still overwhelmed with anxiety. What if the brig does not notice them? What if it is just a mirage created by their collapsing minds?

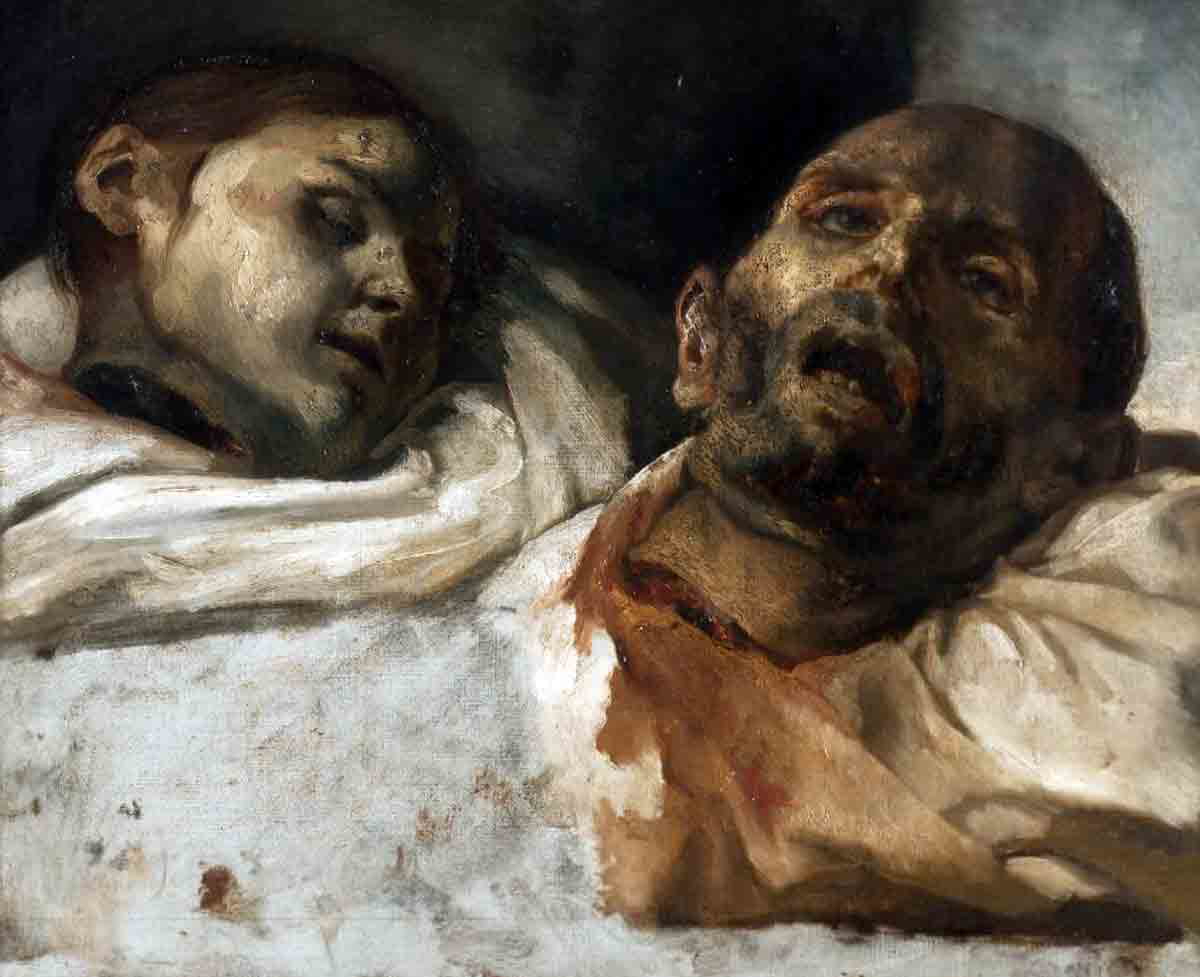

To create a more convincing and realistic scene of suffering, Géricault studied anatomy, attended public executions, and visited morgues and hospitals. Bribing assistants in morgues, he even brought body parts like severed heads and legs into his studio to observe their decay. Thankfully, these naturalistic details did not make it into the painting. Géricault’s contemporaries complained that the artist’s studio emitted a horrible, putrid smell that made everyone sick—everyone except Géricault, who was too immersed in his work to even notice.

Géricault & Delacroix

The young aspiring artist Eugene Delacroix was obsessed with Géricault’s art. Despite their age difference, the two artists developed a friendship. Géricault allowed Delacroix to observe him in the studio and even shared some of his commissions, splitting the profits with him.

Géricault had the predominant influence on Eugene Delacroix’s art, with the latter artist adopting similar contrasts and dramatic gestures. In his oeuvre, The Raft of The Medusa found its conceptual twin in the famous painting The Death of Sardanapalus, depicting the final tragic scene legend of the Assyrian King Sardanapalus who ordered the killing of all his slaves and concubines before burning himself on fire to avoid being captured by the enemy. Despite depicting a most likely fictional story, Delacroix retained the same sense of hopelessness and desperation in the face of violence.

Delacroix played a surprising role in creating The Raft of the Medusa. He was one of the models for Géricault, yet he is almost impossible to recognize due to his figure’s position. Delacroix posed as one of the dead bodies, lying face down in the foreground of the painting, with his hand stretched towards the viewers.

Reception of “The Raft of the Medusa”

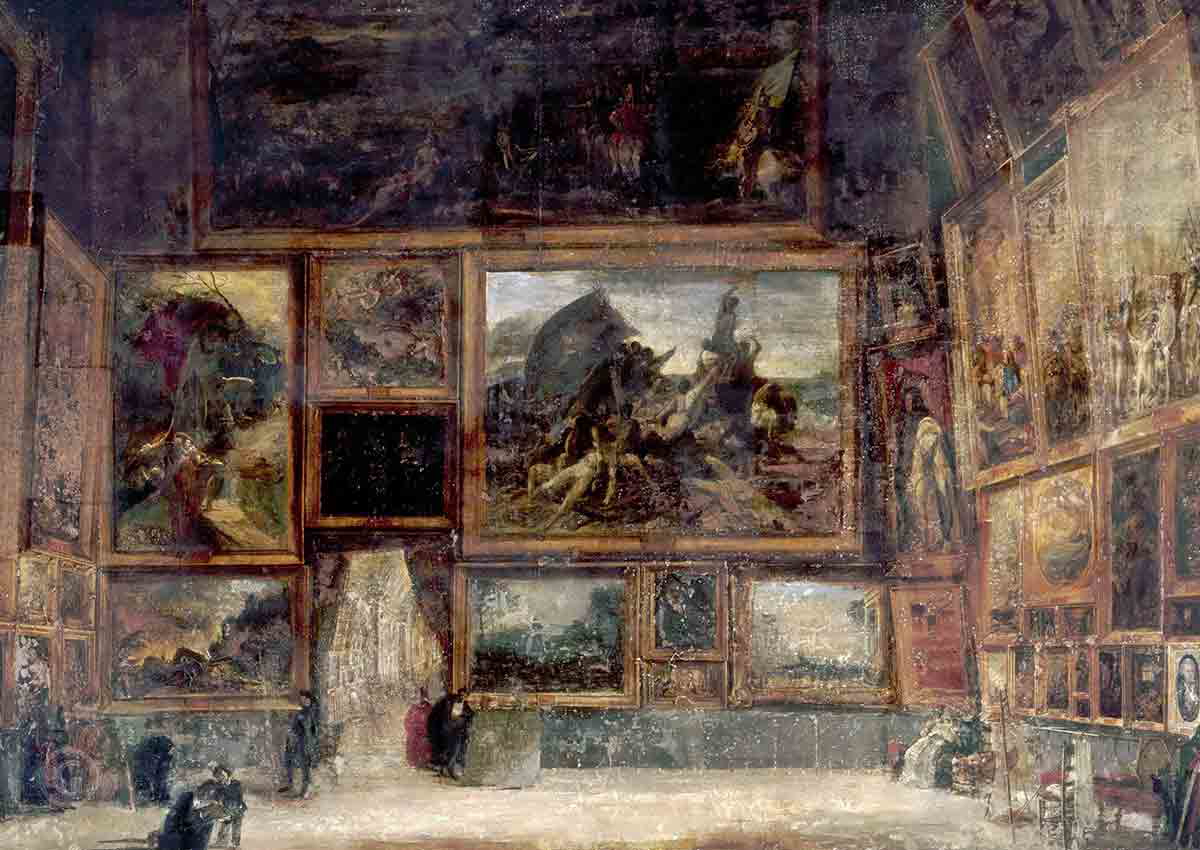

Géricault presented his work for the first time at the 1819 Paris Salon under the title Shipwreck Scene. The horror and trauma of the Medusa catastrophe were still fresh, and despite the generalized title, viewers could not mistake it for anything else. The rest of the Salon was filled with works glorifying the French monarchy and the state, and some visitors wondered how Géricault’s painting even made it to the show.

Critics noted that instead of exhausted and sick figures, Géricault painted athletes with muscular bodies. This step away from realism turned the painting from documentary evidence into a dramatic work. The size of the painting made the dark composition even more impressive and immersive.

Royalists criticized not only the painting’s message but also its subject matter, which was seen as unworthy of such scale and dramatism. They also criticized Géricault’s compositional choices and color scheme. Conservatives looked for errors in drawing and proportion. At the same time, the pro-Republican opposition eagerly praised the work. Still, the true breakthrough happened during Géricault’s tour to Britain, where he received both praise and financial support. The artist died five years after completing the work, which was soon bought by The Louvre.

In the following decades and centuries, The Raft of the Medusa turned into a prime example of gruesome dramatism and the iconic painted composition. It inspired generations of artists and even filmmakers, including the famous Surrealist Luis Bunuel. References to Géricault can be found in the works of Auguste Rodin and William Turner, among others. The painting also challenged the hierarchy of artistic subjects, being one of the rare instances of contemporary non-heroic events considered worthy of large-scale artwork.