In The Last Samurai (2003), a group of 19th-century Japanese warriors rebel against the government because it abandoned the katana in favor of guns. In the end, the last of the samurai perished during the Battle of Shiroyama, pitching blades against bullets in a last-ditch attempt to preserve traditional Japanese culture. Or so the movie claims. In reality, the samurai not only fought for something far less noble, they also relied heavily on firearms, which their class had mastered 300 years prior.

Match, Lock, and 300,000 Smoking Barrels

To understand the events of the Battle of Shiroyama (September 24, 1877), we will have to go back to the 16th century. In 1543, a Chinese vessel carrying Portuguese sailors was blown off course by a typhoon and made an unplanned stop on the Japanese island of Tanegashima. It was the first documented interaction between Japan and Europe. The island’s feudal lord acquired two arquebuses from the Portuguese and then gave them to his craftsmen. Over the following years, they were able to reverse-engineer the design and produced over 300,000 Japanese matchlock guns known as tanegashima or hinawaju (fire-rope gun), which quickly appeared on the battlefield.

Japanese guns were first used in combat during the 1548 Battle of Uedahara when the Murakami clan deployed 50 arquebuses against the legendary warrior Takeda Shingen. At the time, firearms were the weapons of foot soldiers because of their relatively low learning curve. However, the fire-rope guns did not immediately revolutionize Japanese warfare. The arquebuses of the period were too limited. Their short range, vulnerability to rain, and slow reloading made them less effective than a seasoned archer. But, little by little, with improvements in technology and the invention of new battlefield tactics, they became a staple of Japanese battles, with samurai picking up marksmanship as another weapon in their arsenal. They honed that skill and kept it alive all the way until the late 19th century and the last stand of the samurai.

Will the Real Last Samurai Please Stand Up?

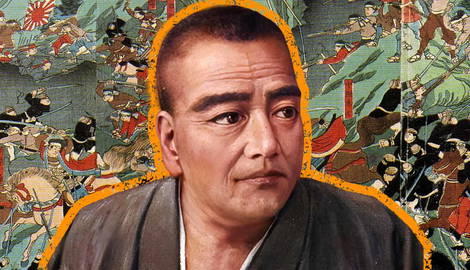

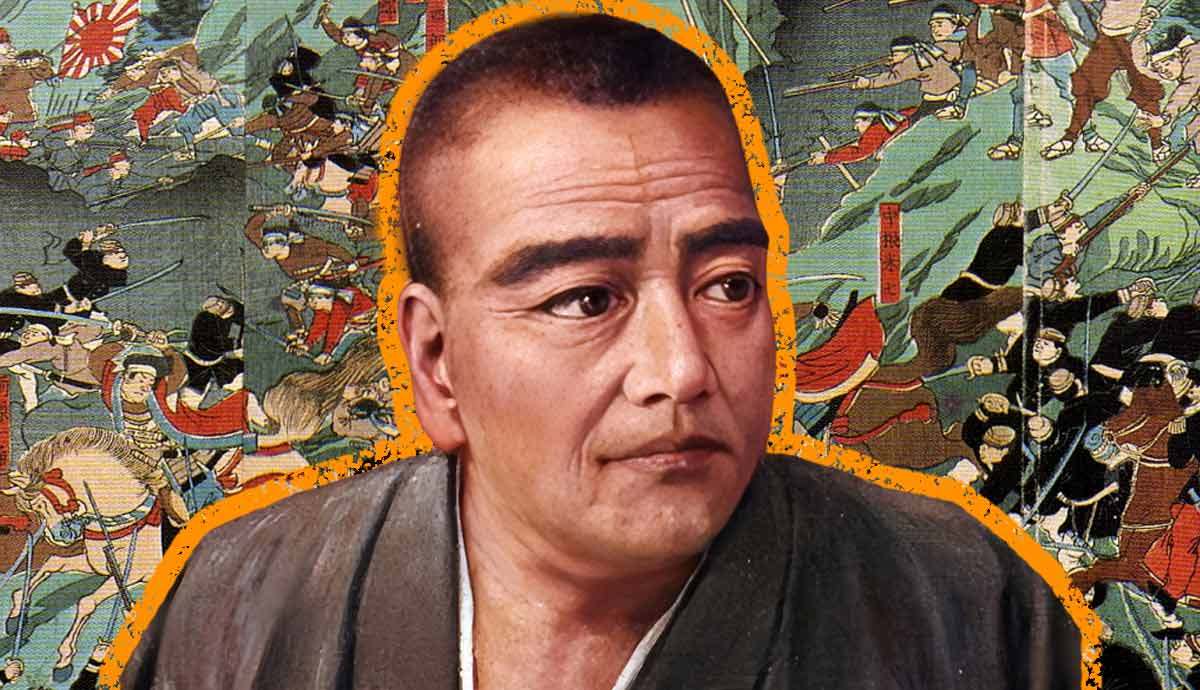

The Last Samurai makes no mention of Shiroyama and casts Ken Watanabe as Moritsugu Katsumoto, leader of the last stand of Japanese knights. But the character and the entire plot of the movie are a thinly-veiled retelling of the real-life Satsuma Rebellion, which did end at Shiroyama and was led by Saigo Takamori. Once a key figure in the Satsuma-Choshu Alliance that was instrumental in the toppling of the shogunate and the restoration of imperial power under Emperor Meiji, Saigo, like Katsumoto, was a supporter of the emperor but eventually removed himself from government. It had nothing to do with his dislike of modernization or firearms.

In The Last Samurai, Katsumoto is seen living in a secluded mountain village and devoting himself to traditional Japanese arts that bordered on asceticism. The real Saigo Takamori, on the other hand, was a practical soldier. He admired the European powers for their proficiency in warfare, owned and frequently wore a Western-style army uniform, and personally met with British arms dealers to supply his Satsuma domain (modern-day Kagoshima) with firearms of all shapes and sizes.

Saigo Takamori also opened private schools throughout Satsuma (Tubielewicz, 1984, p. 359) that were essentially military academies mixed with cults, as they required literal blood oaths and taught everything from military history to artillery tactics and Western-style engineering. That is not to say that Saigo abandoned his katana. He acknowledged that swords cannot deflect bullets, but he still saw himself as a samurai, an heir to a tradition going back many centuries. So did many of his contemporaries. That is one of the reasons behind the Satsuma Rebellion and the Battle of Shiroyama.

Saigo Takamori and 19th-Century Samurai Were… Complex Figures

Saigo Takamori left his government position because the emperor did not want to invade Korea where the recently-sent Japanese delegation was treated coldly (Tubielewicz, 1984, p. 356). Saigo wanted blood to restore the “honor” of Japan, though a chance to test out some of those Western military tactics and weapons was definitely also a factor. With his bloodlust unquenched, he retreated back to his home province where many samurai who fought for the new emperor were finding themselves feeling left out.

Though Shinto and Buddhism had coexisted and frequently intermingled for well over a millennium in Japan, the new government firmly separated the two, making the emperor the protector of Shinto (lessening the role of Buddhism) and taxing some lands belonging to temples. For centuries, samurai had been adherents of Zen Buddhism, and suddenly they were feeling as if their religion was being relegated to second place (Totman, 2016, pp. 300-301). That did not sit well with many. Though not as much as suddenly being equal to peasants. Emperor Meiji did away with the feudal system, freeing commoners from the obligation to literally fall flat on their faces in the presence of samurai. Farmers and merchants were now also allowed to ride horses, have surnames, and, worst of all from the point of view of Japan’s ex-warrior caste, serve in the Imperial Army.

All that anger was not just a question of elitism. Low-ranking samurai were left basically destitute by the sudden abolition of the feudal system that used to supply them with rice or money. In its early years, the Meiji Restoration failed to offer them a viable alternative. The government bailed out the big feudal lords with subsidies and bonds but mostly ignored the little guys, something that a lot of people from all walks of life can recognize as an understandable source of anger. In this rapidly changing atmosphere of confusion, anxiety, and a feeling of being forgotten after shedding blood for a glorious future that never came, the seeds of the Satsuma Rebellion first started to sprout.

Full Metal Samurai

While on the surface being very grateful for his role in helping defeat shogun loyalists, the Meiji government was worried about Saigo’s military schools. To make sure they would not lead to any rebellions, Tokyo decided to confiscate all their firearms and gunpowder in 1877 (Tubielewicz, J., 1984, Historia Japonii, 362.) Ironically, this led to a rebellion. When a ship arrived to take away Satsuma’s guns, the local authorities—most of them graduates of Saigo’s academies—raided the ship and took control of the domain’s arsenal with help from over 1,000 samurai. Saigo was away when it all happened, and when he came back, he found himself in the middle of an insurrection in want of a leader. He decided to take on that role.

Saigo gathered 15,000 troops and marched towards Tokyo to tell the emperor that his advisers did not have his best interest at heart. To make sure they would not be stopped, the Satsuma rebels carried with them Snider-Enfield rifles, carbines, pistols, about 1,500,000 rounds, pack howitzers, field guns, and dozens of mortars (Buck, J. H., 1973, The Satsuma Rebellion of 1877. From Kagoshima Through the Siege of Kumamoto Castle, 431). By the time they got to Kumamoto Castle, under the command of imperial loyalists, the last samurai were ready for a shooting battle.

The Satsuma Rebellion Started and Ended With a Bang

During the Siege of Kumamoto Castle, Saigo set up cannons around the fortification and bombarded it mercilessly (Turnbull, 2003, p. 198). Finding themselves insufficiently prepared, the soldiers at Kumamoto at one point resorted to digging up unexploded rebel ordinances in order to have something to shoot at the enemy (Turnbull, 2003, p. 199). While swords made occasional appearances during sorties and skirmishes, the siege was very much all about firepower. Things were looking up for Saigo Takamori, but the situation quickly changed after the Imperial Army showed up. Through months of battles, surprise attacks, encirclements, Saigo was forced to keep retreating. In the end, he was left with only 500 fighters and by some miracle seized Mount Shiroyama where he planned to make his last stand.

At this point, Saigo had lost most of his firearms. In the final days of the Satsuma Rebellion, his army apparently started melting down bronze statues for bullets. He knew that Shiroyama would be his grave so he went back to basics. He burned his army uniform, exchanged cups of sake with his officers, did a ceremonial sword dance, and wrote a traditional death poem. Though the Imperial Army outnumbered the rebels 60-to-1, they were not taking their chances and “reduced their numbers” via heavy artillery fire. When only 40 rebels were left, there was a full-frontal assault where Saigo’s men relied on their katana swords, and that part may have looked a little bit like the very end of The Last Samurai. Severely wounded by a bullet, Saigo ended up finding a quiet spot on the battlefield to commit seppuku. Thus ended the last stand of the samurai on the slopes of Shiroyama.

Bibliography

Buck, J. H. (1973). The Satsuma Rebellion of 1877. From Kagoshima Through the Siege of Kumamoto Castle. Monumenta Nipponica, 28(4). pp. 427-446.

Totman, C. (2016). A History of Japan, Second Edition. Blackwell Publishing.

Tubielewicz, J. (1984). Historia Japonii. Ossolineum.

Turnbull, S. (2003). Samurai—The World of the Warrior. Osprey Books.ar