Henry VII often slips through the cracks of history, being sandwiched between the controversial Richard III, a Renaissance Machiavellian prince, and Henry VIII, an impossibly charismatic and epoch-shaping monarch. But without Henry VII, there would be no Henry VIII. It was Henry VII who ended a civil war and took the English crown for the Tudors.

Welsh Origins of the Tudors

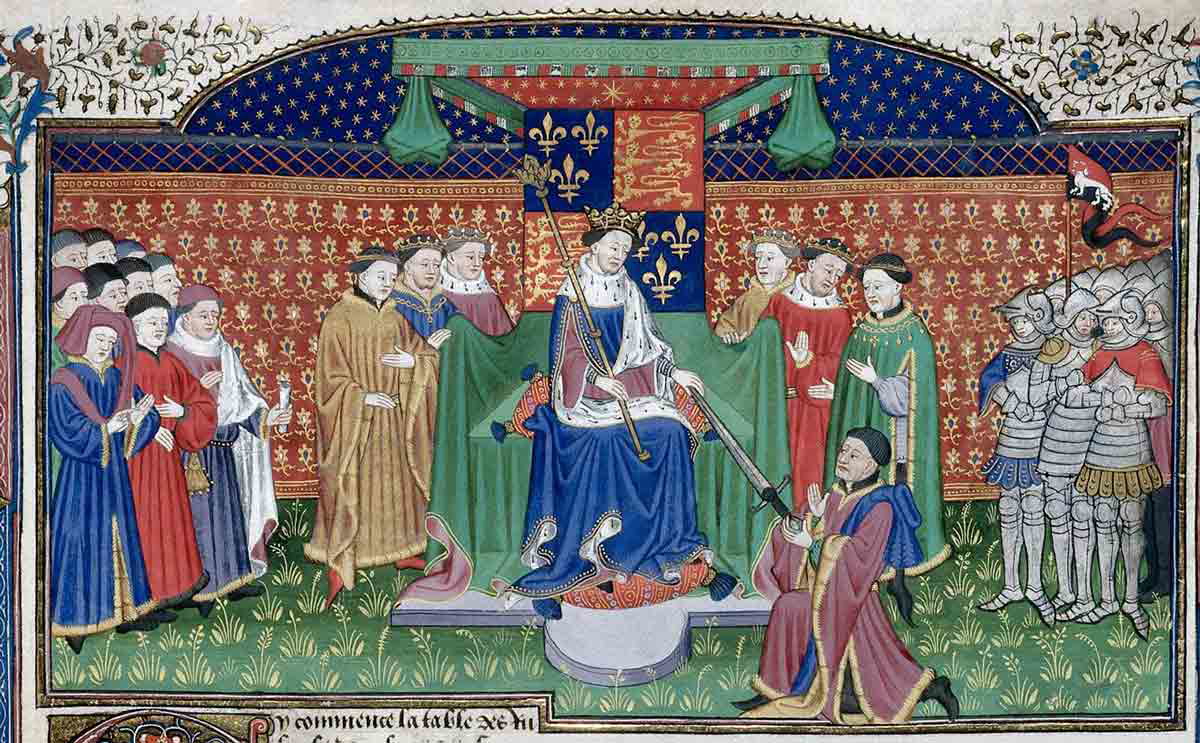

Observers of English heraldry will notice that the Tudor coat of arms features a red dragon opposite a white greyhound. The dragon is a nod to the surprising Welsh ancestry of the Tudor dynasty. Mostly forgotten today, their roots in the Welsh principality meant a huge amount to the early Tudors. This was still the era of Arthurian romance and prophecy. The Tudors were not shy about seizing upon this to help legitimize their rule.

It is possible to exaggerate Henry VII’s emergence from obscurity. He was, after all, the Earl of Richmond. He came from a family of Welsh lords from the distant Isle of Anglesey who claimed descent from Cadwaladr, supposedly the last ancient British king. One of his ancestors served in the court of Llewelyn the Great. The next significant Tudor was Owen, whose father participated in Owain Glyndwr’s uprising against the English between 1403 and 1406.

Much of Owen’s life is mythologized, and he may or may not have served in the court of Henry V of the House of Lancaster. He ended up marrying Henry V’s widow, Catherine of Valois. This meant his progeny were half-brothers of Henry VI. In the early stages of the Wars of the Roses, this positioned them to climb the courtly hierarchy and accumulate forfeited Yorkist lands. Both Edmund and Jasper Tudor became senior earls in the royal court. The former was made Earl of Richmond and was to marry Margaret Beaufort, daughter of the Duke of Somerset and a descendant of Edward III.

Henry in Exile: Brittany’s Court

The Tudors walked a tightrope in the very early stages of the Wars of the Roses between loyalty to their “Lancastrian” half-brother and the reality of the rising power of Richard of York, who claimed protectorship over the kingdom during Henry VI’s mental breakdown. When the king recovered, civil war broke out. Edmund Tudor was captured defending forts in South Wales in Henry’s name and died in captivity. Edmund’s young son, Henry, and his mother fell under the wardship of the Yorkist William Herbert during the reign of Edward IV, Richard of York’s son, who defeated the Lancastrians in 1461. Edmund briefly attended court when Henry VI returned in 1470 but went into exile when Edward retook the kingdom the following year.

The next few years were tenuous for Henry. Not only was he now a noted Lancastrian, but via his mother, he had a distant but real claim to the throne. This made him a target for the Yorkist regime. He went into the protection of Francis II, Duke of Brittany. He and his uncle Jasper were rotated between various forts in the south of the dukedom and its capital, Nantes. His mother remained in England, trying to arrange circumstances for a possible return. It was during this time that a potential marriage to one of Edward IV’s daughters was first suggested.

Henry’s time in Brittany was precarious. Edward IV made constant entreaties to try and secure Jasper and Henry. Although they started life in the duchy with 500 Lancastrian allies, these were gradually stripped away until they were guarded only by Breton soldiers. Still, it was at this time that Henry learned the necessities of European noble life. He hunted, took part in contests, practiced his archery, and learned court form. Observers complimented his manners and mastery of French. It’s likely he also picked up Breton, a language similar to Welsh.

Henry Evades Capture

In 1476, not for the last time, Francis II fell ill. His advisors reached an agreement with the Yorkists and handed Henry over to English delegates who prepared to take him back. There are claims that Edward IV actually planned to marry Henry to his daughter, as Henry’s mother had planned. The king was confident that his own sons would succeed him and the Tudor/Lancastrian claim would finally be neutralized. Whatever the truth, Henry refused to go until he was coerced. Thus, on a cold November day at the Breton port of Saint-Malo, Henry looked out across the sea towards his home but also to imprisonment and possibly death. Out of desperation, he faked stomach cramps. The English envoys fell for it long enough that they missed the tide.

Forced to remain for a little longer, Henry was saved by circumstance. A Breton noble arrived with the message that Francis had recovered. Henry took full advantage of the confusion, slipped away, and ran. He was chased through the streets to St Vincent’s Cathedral and claimed sanctuary. The town’s citizens rallied and blocked the entrance to his pursuers. The envoys attempted to wait him out but eventually returned to Westminster. Henry had survived.

Later that year, the French king—Louis XI—made his own attempt to secure Henry and Jasper, presumably to use them as bargaining chips against England. However, his efforts were to no avail. He tried again in 1477 and 1482, offering greater sums of money and military support. Francis and the Tudors stood firm.

Plantagenet Alliances

In 1483, Edward IV died, and his brother, Richard III, usurped the throne from his children on spurious claims of illegitimacy. As it became clear that Edward’s sons, the Princes in the Tower, had been murdered, Henry Tudor’s tenuous, distant claim grew in significance. He now became an important pawn for both the duke of Brittany and the king of France.

As a potential rival claimant, and a cousin of Louis XI, he was important leverage for the Bretons to prevent an English accommodation with the French king, which might threaten their ducal independence. Henry was politically useful but practically weak. He was utterly dependent on the hospitality of the Bretons. He must have feared that, at any moment, events could turn in and see him handed over to the Yorkists.

However, Henry wasn’t immediately at the forefront of issues in England, where the focus was on Richard. It is unclear whether the duke of Buckingham, Henry Stafford, the main conspirator of the 1483 rebellion, was revolting in Henry’s name or in his own. We do know, however, that Margaret Beaufort, Henry’s mother, began pushing her son as a candidate. Regardless, a series of events now combined to push Henry to prominence.

What is often missed in the narrative of these months is the change of circumstances in France as well as England. In August, Louis XI died and so did the immediate threat to the power of the Breton dukes. Brittany was now free to openly oppose Richard, possibly in spite of his refusal to provide military aid against the French, but also perhaps because Edward V—now presumed murdered—had been betrothed to the duke’s daughter. Duke Francis supported Henry with an attempted naval expedition to coincide with Buckingham’s revolt.

Despite bad weather, Henry and his fleet eventually reached the coast of either Plymouth or Poole. Henry did not land and instead retreated to avoid capture. His failure to land, and the rebellion’s failure, may have played in his favor. This left him as the last remaining figurehead against the regime. Hundreds of sympathizers—united more by their opposition to Richard than any devotion to the Tudor claim—flocked to Brittany. They were encouraged by Edward IV’s widow’s family, the Woodvilles. Shakespeare had the widowed queen tell loyal nobles to “cross the seas, and live with Richmond, from the reach of hell.” By Christmas, Henry and his counselors had drafted and sworn to a manifesto, with Henry vowing in Rennes Cathedral to marry Elizabeth of York, sister of the Princes in the Tower, to strengthen his claim and unite the Plantagenet factions.

Henry Becomes a Serious Contender

Despite the momentum, things were still on a knife-edge for the Tudors. Political chaos in Brittany in the following year led to the duke effectively being overthrown by a regency, which proceeded to secure a truce with Richard and agree to hand over Henry. In October, Henry was forced to flee to France. His prospects now looked bleak. Although the French were in a quasi-war with Richard, the court was too absorbed in its own political infighting to consider an invasion of England. Henry needed to demonstrate that he could command loyalty and that he was a serious contender.

Then, in November, luck turned again in Henry’s favor. John de Vere, the Lancastrian Earl of Oxford, who had been imprisoned in Hammes Castle in the Pale of Calais, managed to persuade his Yorkist gaolors to defect to Henry. The castle itself was retaken by loyal Calais troops, but not before Henry’s own military intervention secured the escape of much of its garrison for future use. Now, he could prove he was capable of inspiring and leading soldiers and appealing to Lancastrians and Yorkists alike. This was supplemented by a flow of further defections and funds channeled from his mother.

Richard issued a proclamation against Henry and Jasper in December and started preparing defenses. Henry was, finally, a serious threat to the Yorkists and a king-in-waiting. In March 1485, the political situation in France stabilized enough under a new regent, Anne de Beaujeu, that it could throw its financial and military backing behind Henry and his small army to depose Richard.

Henry still faced an uphill task. First, he had to cross the channel, avoiding Richard’s new Breton allies and the English fleet. Then, he had to land and hope he could rally enough support and men to challenge the Yorkist army. He would likely be outnumbered and against the full resources of the English state. The Tudor plan was to repeat Henry IV and Edward IV’s trick of landing in their heartlands, in their case, Pembrokeshire in Wales, and hope that the old ties of loyalty would be enough to rally support. In fact, they had already received intelligence of loyalty from their Welsh lands, where poems and songs were already being written proclaiming him as the returned Arthur. Nevertheless, they would have to engage Richard as quickly as possible. The longer they waited, the more time Richard would have to amass reinforcements and secure territory.

The Return of the King

The Tudor plans worked. After avoiding the Breton and English fleets, Henry landed in Mill Bay at the south-west tip of Wales, kissed the soil, and recounted a psalm. His army pointedly disembarked with banners bearing both the Cross of St George and the Red Dragon. Again, he played to his Welshness, promising the Welsh gentry that he would free “our Principality … of such miserable servitude.” The Tudor army swelled as it marched across south Wales and into central England. Richard’s officers either declined to intervene or outrightly defected. As planned, the army made rapid progress, marching as much as 20 miles or more a day across Wales before passing into Shropshire. Throughout, Henry was furiously writing letters and dispatching messengers as he tried to rally support from key nobles like the Stanleys.

They engaged Richard’s larger army at Bosworth in Leicestershire. Henry was outnumbered, but the inactivity of the Earl of Northumberland—for reasons still debated—and his entreaties to the Stanleys helped ensure their late intervention in his favor and Richard’s defeat. In hindsight, this isn’t surprising. Lord Thomas Stanley was not only Henry VII’s stepfather, but the family had been treated poorly by a suspicious Richard, holding Thomas’ son hostage to secure his “loyalty.”

Significantly, it was a Welshman who dealt the likely deadly blow to Richard’s skull. The discovery of Richard’s remains in 2012 and the accompanying head wound has served to add veracity to sources about the battle that were previously assumed to be unreliable. Therefore, we can perhaps now be fairly confident that the dead king’s circlet was indeed found and brought to Henry by Lord Stanley, signifying the handover of power.

Through his own resourcefulness, determination and cunning, Henry navigated the chaos of the Wars of the Roses. Yet, there he stood, as one foreign source put it, “without power, without money, without right to the crown of England, and without any reputation but what his person and deportment obtained for him.”

Securing the Throne

It’s easy to assume, with hindsight, that the rise of Henry VII and his dynasty were inevitable. In fact, insecurity and the bloody memory of the Wars of the Roses made Henry’s first years incredibly uncertain. Henry therefore moved cautiously and generously in his early years, benefitting his supporters but also relegitimizing the Princes in the Tower and his new wife and excusing former Ricardians who fully submitted. A Yorkist rebellion, claiming the pretender Lambert Simnel as the son of the elder brother of Richard III, the Duke of Clarence, erupted out of Ireland in 1487. There were further rebellions in 1489 in Yorkshire and, from 1490, there were periodic landings by Perkin Warbeck, a Fleming who claimed to be Richard of Shrewsbury (one of the Princes in the Tower). One of the Stanleys, William, who had become a key figure in Henry’s own household, was found to have money likely meant for Warbeck’s cause and was executed.

Nevertheless, Henry’s early generosity and active, but not always popular, government ensured his survival. His broad policy of peace and trade abroad, justice at home, and non-interference with loyal nobility meant that his reign just about had a wide enough base of support to endure and overcome threats from within. The real story of Henry VII, then, is not his unlikely, heroic and captivating rise but his altogether quite forgotten and relatively bland time at the summit. Perhaps it is precisely that forgettability, compared to the melodrama of previous decades and the religious turmoil that was to follow, that is his ultimate tribute.