The Rhine River is constantly mentioned in articles about Rome and the Reich. For the Romans, the Rhine became a physical reminder of the Empire’s limit. Crossing that barrier put the traveler beyond civilization. The Rhine for Hitler’s Third Reich became a catalyst for redressing the Great War’s defeat and a blinding nationalist revival. The Rhine flowed deeply into the psyche for both.

The Edge of Civilization

For the Mediterranean Sea-based Romans, the Rhine River’s winding path became the Empire’s northern border. The Roman legions had reached the Rhine’s edge by 50 BCE, following Caesar’s conquest of Gaul. With the Rhine’s strategic importance now, Rome sought to keep German tribes on the far side. For them, the clash evolved between “barbaricum” and imperial “civitas.”

Barrier, Launchpad, and Gateway

As a barrier, the Rhine averaged 100-300 meters during the Roman era. Though a formidable barrier, German invaders still crossed; the frontier remained volatile, never truly quiet. The Romans took security here seriously, establishing fortified camps like Vetera and Mogontiacum (Mainz). The settlements kept watch and allowed for rapid response along the “Limes Germanicus” or German frontier.

For ease of command, the Romans split the Rhine zone into Germania Inferior and Germania Superior. Eight battle-hardened legions lay stationed along the Rhine, or some 40,000 soldiers. The Empire used the Rhine for annual expeditions, too, hoping to expand imperial reach. However, the 9 CE ambush and loss of three legions at the Battle of Teutoburger Forest changed imperial thinking.

Before this, Rome’s ability to invade, conquer, and assimilate never wavered. The traumatic loss of three legions to Germanic tribes changed this thought.

The Rhine River became a bulwark and one not lightly crossed. To Romans, the edge of the civilized world now existed. Yes, certain tribes emigrated, earning citizenship, but Imperial thought didn’t change. This status quo changed little until winter 406 CE. Here, Germanic tribes broke through the Rhine defenses, invading and settling. Rome’s fall wouldn’t be far off.

The Reich’s River View

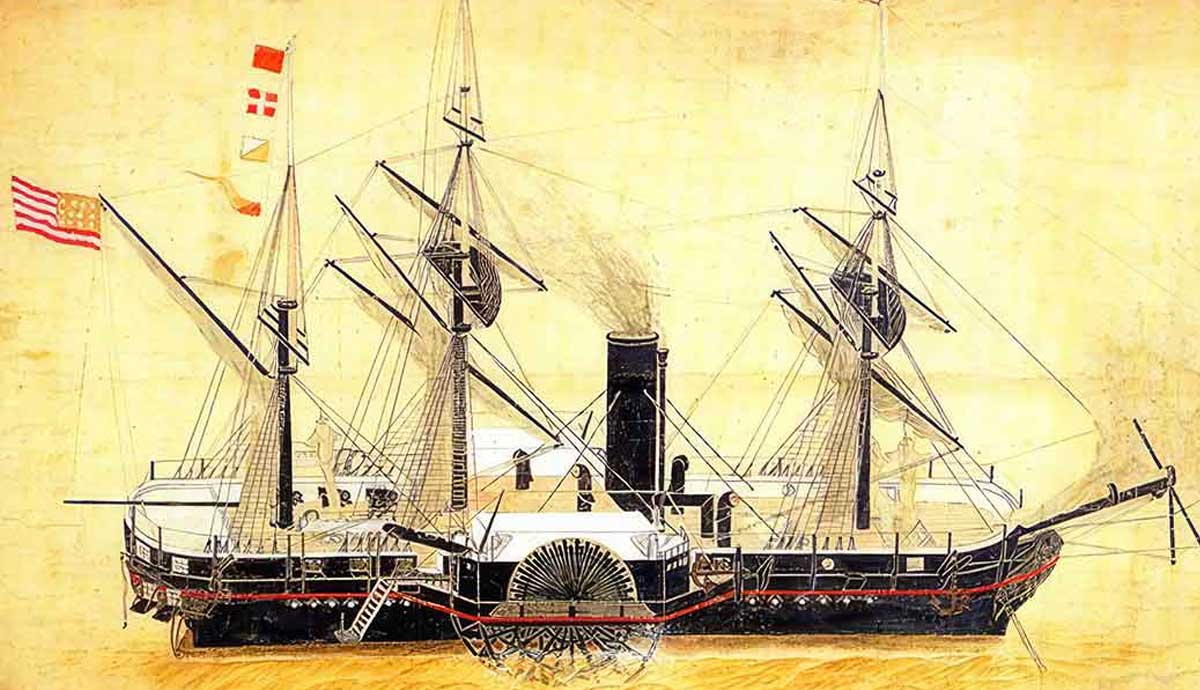

Hitler’s Third Reich viewed the Rhine in different ways—first, in a mythical light. The Rhine signified a connection to Germany’s two previous Reichs. In the First Reich (800-1806) or Holy Roman Empire, the Rhine operated like an artery, connecting the different parts in Imperial cities like Mainz or Cologne. The Second Reich (1871-1918) under the Kaisers viewed their existence as the First Reich, stating the Rhine as a “God given frontier.” To the Reich’s third incarnation, the Rhine stood as a “sacred frontier” echoing their predecessors.”

Secondly, in Nazi propaganda, the Rhine held an ideological significance. The Nazis, especially Hitler, viewed the 1918 Great War defeat as extremely humiliating. As part of the Treaty of Versailles’s reparations, the Allies occupied Germany’s Rhineland. Demilitarized of any German presence, the rump acted as a security buffer.

With Hitler’s takeover in 1933, ending this became one of the Nazi’s primary goals. Under the Nazi’s “Blood and Soil” belief, the Rhine River embodied a border that separated the German racial homeland. This kept the Aryan Volk “racially pure.” The Nazis skillfully manipulated their people, tapping into the Rhine’s historical legacy as a sentinel. Germany’s 1936 Rhineland remilitarization restored the Reich’s west wall. Hitler’s bluff succeeded, wiping out the humiliation. The Rhine’s last chapter came in late 1944-45.

The 1945 Crisis – Defense of the Rhine

The Rhine’s importance as a Nazi symbol peaked in early 1945. Defeat loomed from East and West as Allied armies rolled steadily over the Wehrmacht. In the West, the Rhine stood as Germany’s last natural barrier. Should they cross the river, their greater mobility and firepower meant a rapid Nazi defeat.

Nazi propaganda revved up their propaganda, touting the Rhine. The Rhine became, quite literally, a last bulwark, echoing the late Roman Empire. The Nazis tapped the Rhine’s symbolic power by painting the Rhine as core to the German identity, preventing “foreign contamination.” Propaganda Minister Goebel encouraged the Volk to defend Germany at all costs.

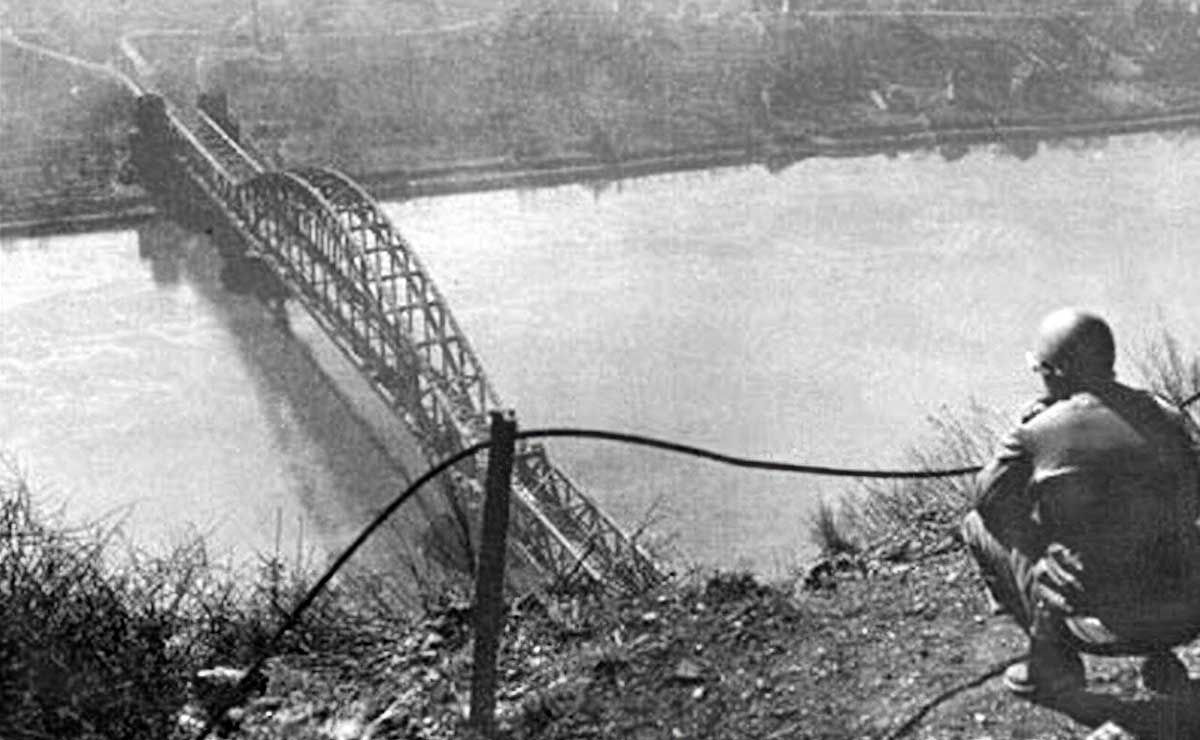

Yet, in March 1945, despite all the exhortations, the Allies crossed the Rhine. The cross-river attacks breached German defenses, despite better resistance. On March 7, the Americans, in a stroke of German misfortune, captured the Remagen bridge, giving them an intact crossing. Once established across the river, nothing could dislodge them.

The incredibly successful crossings shattered the Rhine’s mythology. Nazi propaganda faltered, unable to spin a yarn as German morale plummeted. Now, no part of Germany was safe. The Rhine’s symbol to Imperial Rome and the German “Reichs” psyche as barrier, heartland, and border can’t be underestimated. To them, the Rhine was a central belief.