The Second Triumvirate was very different from the First Triumvirate, which saw Julius Caesar, Pompey Magnus, and Crassus, three of the most powerful men in Rome in 60 BCE, form a secret alliance to further their political agendas. The First Triumvirate would ultimately result in civil war. In contrast, the Second Triumvirate was formally constituted in Roman law, initially in 43 BCE, to grant Caesar’s three heirs, Mark Antony, Octavian, and Lepidus, absolute power over the crumbling Republic. This alliance would also end in civil war and the rise of imperial Rome.

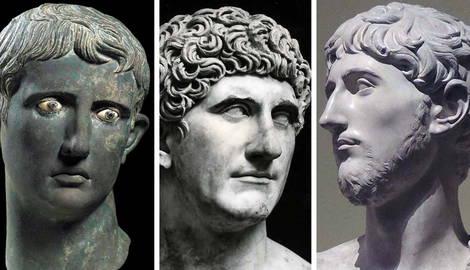

Who Were the Triumvirs?

By 44 BCE, Julius Caesar had won absolute power in Rome, rejecting the hated title of rex (king) but establishing himself as dictator perpetuo (dictator for life). This was too much for many to accept. Caesar was assassinated by a group of senators on March 15, 44 BCE. This left an enormous power vacuum in Roman politics, which Caesar’s three principal heirs fought to occupy.

Marcus Antonius, better known as Mark Antony, was a distant relative of Julius Caesar. He served with Caesar during his conquest of Gaul, and when Caesar was made dictator, several times starting in 49 BCE, Antony served as his Master of Horse (second in command). Relations between the pair soured in 46 BCE and Antony was left as a private citizen, but they reconciled in 45 BCE, and Caesar ensured that Antony was made consul in 44 BCE. Antony was in Rome when Caesar was assassinated and seized control of the state treasury. Caesar’s widow Calpurnia presented him with Caesar’s personal papers, essentially recognizing him as Caesar’s successor.

Marcus Aemilius Lepidus was another one of Caesar’s important military allies. He was left in charge of Rome in 49 BCE while Caesar battled Pompey in Greece and then served as governor of Hispania. He served as consul in 46 BCE and was then made Caesar’s new Master of the Horse. He was also in Rome when Caesar was killed and occupied the Campus Martius with troops. Along with Mark Antony, he negotiated an initial truce in the wake of the assassination and was appointed as Caesar’s successor in the position of pontifex maximus (chief priest).

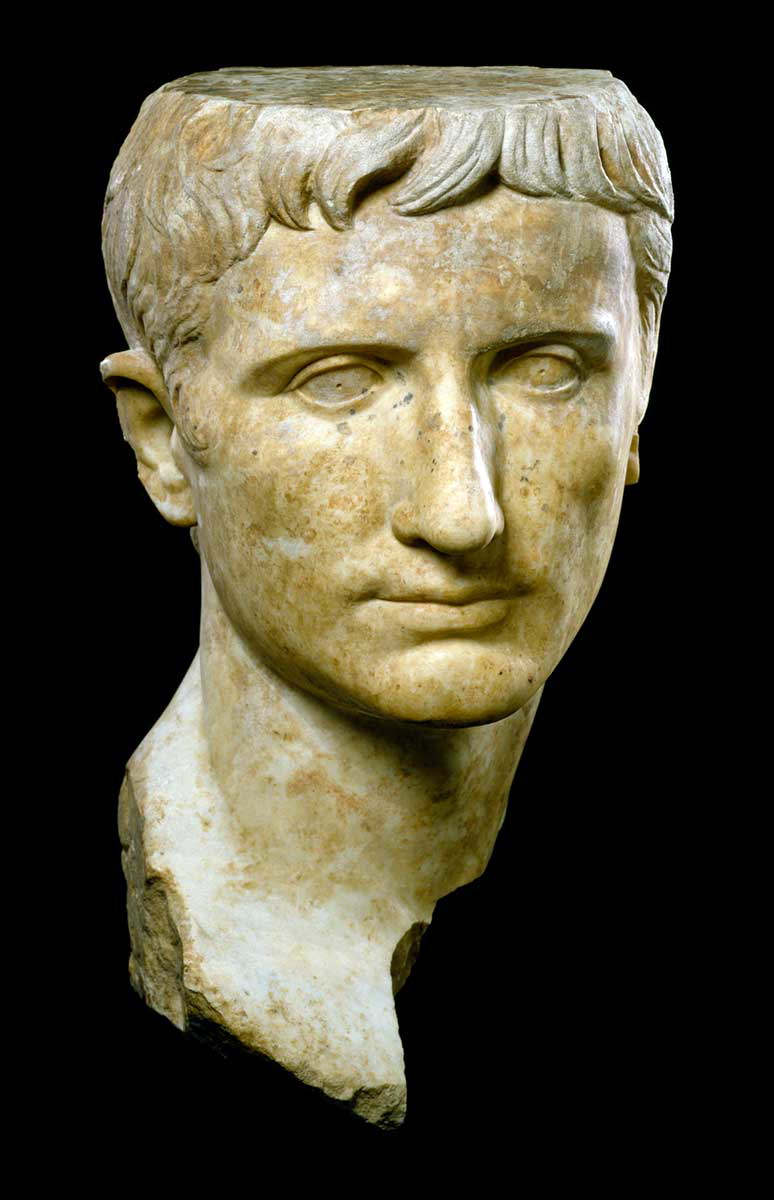

Gaius Octavius, better known as Octavian and later as Augustus, was the great-nephew of Julius Caesar. In 46 BCE at the age of 17, Octavian was set to join Caesar on a campaign in Hispania and start his military career, but he fell ill and was unable to travel. He later traveled to join Caesar alone, suffering a shipwreck and crossing hostile territory to reach his great-uncle’s camp. It was, reportedly, after this demonstration of courage that Caesar decided to adopt Octavian in his will, which he deposited in the temple of the Vestal Virgins, as was the custom.

Octavian was completing his military training in Illyria when Caesar died. He immediately made his way to Rome. Landing in Italy, he received confirmation that he had been adopted as Caesar’s heir and received two-thirds of his estate. Antony initially challenged Octavian’s adoption and refused to hand over funds that were his due.

The First Settlement With the Liberatores

Following Caesar’s death in 44 BCE, there was initially a settlement between Caesar’s supporters and his assassins, who styled themselves the liberatores (liberators). This included confirming the validity of Caesar’s actions while in office, amnesty for his assassins, and the abolition of the position of dictator, theoretically so that no one could accumulate so much power again. Power was divided between important players on both sides, with many given provincial commands.

While he may have negotiated the initial settlement, the ambitious Antony pushed through legislation that allowed him to illegally take control of Cisalpine Gaul and Transalpine Gaul from their appointed governors. This gave him control of large Caesarian armies just outside Italy, so he could menace the Senate and force their cooperation. He convinced the Senate to strip Caesar’s two principal assassins, Brutus and Cassius, of their military positions and assign them to grain supply roles. This was considered an insult and set the scene for renewed conflict.

Meanwhile, Octavian was looking to secure his position among the Caesarians currently under Antony’s command. In the eyes of many, Octavian had the superior claim. He started to attract the loyalty of many of Caesar’s veterans, especially the most extreme, forming a personal army. He placed himself in opposition to Antony by supporting the governors of the Gallic provinces who had been displaced.

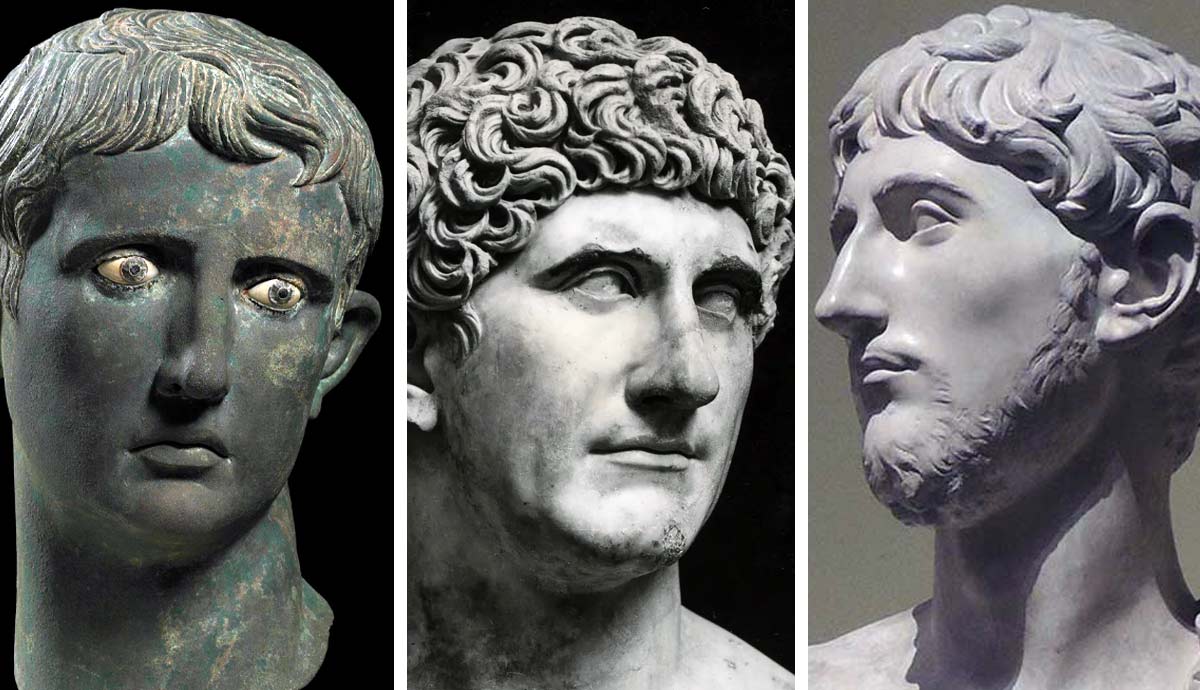

In December of 44 BCE, Cicero, a long-standing adversary of Mark Antony in the Senate, took Octavian’s side, convincing the Senate to honor the youth and support his move against Antony. Octavian and the two consuls then led the Senate’s forces against Antony, putting him to flight at the Battle of Mutina in April 43 BCE. Cicero took the news of the victory as an opportunity to have Antony declared a public enemy. But Octavian had his eye on power. Both the consuls died in the conflict, so he marched to Rome to secure the consulship for himself.

Octavian used his new power to confirm his adoption and condemn Caesar’s assassins. He also repealed the declaration against Antony, with whom he was now prepared to negotiate from a stronger footing.

Creation of the Second Triumvirate

Octavian and Antony met in late 43 BCE, with Octavian traveling to meet Antony under the protection of Lepidus. An agreement was struck between the three and sealed by Octavian marrying Antony’s stepdaughter Clodia. The three men called themselves triumviri rei publicae constituendae, which identified them as three men with responsibility for restoring the Republic. With the cooperation of a friendly Tribune of the Plebs, the Lex Titia was passed, granting them extraordinary power for a period of five years.

Far more than resembling the private agreement of the First Triumvirate, the agreement was modeled on the Lex Valeria of 82 BCE which established Sulla as dictator and gave him extraordinary powers to reform the Roman constitution. They all received the power to issue legally binding edicts, they were given imperium maius, which gave them superior military command over Rome’s consuls and provincial governors, and they received the power to call meetings of the Senate and appoint magistrates and provincial governors. These powers placed the triumvirs above the consuls in the political hierarchy, and they used those powers to have Caesar declared a god.

They also used their power to deal with their enemies in Rome through proscriptions, which allowed them to seize the property and wealth of those whose names were placed on the death list to fund their activities. They reportedly had around 300 senators and 2,000 equestrians killed, while others escaped, joining the liberatores forces under Brutus and Cassius or Sextus Pompey, the son of Pompey Magnus who was carving out naval power for himself around Sicily. Cicero was one of the most famous victims of the proscriptions.

The triumvirs gave themselves provincial commands, with Antony continuing with Cisalpine and Transalpine Gaul plus the eastern provinces, Lepidus taking Gallia Narbonensis and Hispania, and Octavian taking Africa, Sardinia, and Sicily. This set the triumvirs up to wage war against the liberatores.

The assassins were defeated in October 42 BCE after two battles at Philippi, mostly thanks to Mark Antony. This secured his position as the senior and most prestigious member of the triumvirate.

Dividing East and West

With Caesar’s assassins dead, the triumvirs could focus on “rebuilding” the Republic. Mark Antony took the opportunity to claim most of Rome’s provinces, including the eastern provinces, Transalpine Gaul, and Gallia Narbonensis. He focused on the east while leaving trusted allies in Gaul to deal with any issues in Italy. Lepidus was given Africa, and Octavian was given the dubious privilege of settling the veterans of Philippi in Italy and leading the war against Sextus Pompey in Sicily.

Antony used his power to move against Parthia, which had supported the liberatores and Pompey, seeking the kind of military honor and respect that Caesar had earned in Gaul. He also focused on building support for himself in the East. He was careful not to tax local communities too harshly and toured cultural centers to honor their history and tradition. He confirmed the positions of allied subject rulers, such as Cleopatra in Egypt.

Meanwhile, Octavian was struggling to settle things in Italy due to famine caused by Sextus Pompey’s naval blockade. Antony’s supporters blamed Octavian for the situation, building support for an uprising against the young Caesar. This led the consuls of 41 BCE, one of whom was Antony’s brother Lucius Antonius, to occupy Rome. They were beaten back by Octavian who besieged them at Perusia, eventually sacking the city but sparing the consuls. He used his victory to take control of Antony’s two Gallic provinces. This essentially split the empire into East under Antony and West under Octavian.

To strengthen his position, Octavian also tried to ally with Sextus Pompeius, marrying Pompey’s sister-in-law Scribonia in 40 BCE. But Sextus was playing both sides and started raiding southern Italy while Antony returned to reaffirm his position. Octavian and Antony eventually met at Brundisium, and while there were skirmishes, they ended up negotiating a new agreement.

Octavian’s power in Gaul was confirmed. He was also granted Illyricum and the right to deal with Sextus Pompey, either through treaty or war. Antony was made master of the East and given responsibility for the campaign against Parthia. Lepidus was still limited to Africa. Amnesty was granted to all former Republicans. While Italy was not awarded to anyone, Octavian’s presence in Italy left it largely under his control. This treaty was sealed by another marriage, this time of Mark Antony to Octavian’s sister Octavia.

In 37 BCE, the powers of the triumvirs were renewed for another five years. Their current powers had expired at the end of 38 BCE, at which time it would have been normal for a magistrate to abdicate, but the triumvirs chose not to do so. To maintain the illusion of constitutional power, the three worked together to officially renew their powers for another five years, now set to expire at the end of 33 BCE.

Mark Antony in the East

Mark Antony was now free to focus his attention on the East, which required a change in strategy. Winning support among the Romans with their militaristic and disciplined society was different from ingratiating himself in the decadent (according to the Romans) East, where the people were accustomed to worshiping their kings as gods. Playing up for the local audience, Antony identified with the god Dionysus and allowed the locals to venerate him.

Antony’s actions in 36 BCE were more political than military, largely due to internal dynastic struggles within Parthia. Antony used the opportunity to strengthen relationships with local client kings, such as Herod in Judaea and Cleopatra in Egypt. In particular, he fathered a son on Cleopatra and publicly acknowledged both this son and the twins she had in 40 BCE. Moreover, he gave the Egyptians Crete and Cyrene, in theory giving away territory that belonged to Rome. Antony probably meant for Egypt to be his new base and wished to reinforce his position there, but this made him unpopular in Italy.

War would eventually come with Parthia when Antony demanded the return of the military standard taken from Crassus, and the Parthians refused. Antony marched through Armenia and into Persia, and then quickly moved towards the Parthian capital. But he was impatient, leaving his siege engines behind, and was also abandoned by his Armenian allies. Consequently, he was forced to retreat, which cost him about a third of his army. This, combined with his other activities, damaged Antony’s reputation.

Octavian in the West

Octavian was also active on the military front, allying with Lepidus to deal with Sextus Pompey once and for all in 36 BCE. While Octavian was personally defeated, his campaign was successful thanks to his general and close friend and ally for decades, Marcus Agrippa.

Lepidus, encouraged by his participation in the victory, attempted to negotiate with Octavian to expand his territory. But Octavian saw this as an opportunity to get rid of Lepidus. He reportedly walked into Lepidus’s camp alone and won over the loyalty of his troops. Disenfranchised, Lepidus was stripped of his triumviral powers and provincial command. While he was allowed to live and retain the office of Pontifex Maximus, he spent the rest of his life in exile.

But more important than Octavian’s military campaigns was his propaganda campaign against Antony. He highlighted how Antony was no longer a Roman general, but styling himself an eastern king. It was only a matter of time before he tried to make himself king in Rome. Was it not Antony who had offered Julius Caesar the diadem that he had refused? Antony did not help himself by participating in a religious procession in the guise of Dionysus in Alexandria and crowning his children with Cleopatra as oriental monarchs.

While the Antonians made counter-propaganda campaigns, accusing Octavian of being a coward, treating Lepidus poorly, and stealing the wives of ex-consuls, referring to his marriage to Livia in 38 BCE, Octavian won the war of opinion. He started preparing his troops, training them in Illyricum, and leading them to easy victories over local tribes. He was waiting for the right moment to strike against Antony.

End of the Second Triumvirate

Things came to a head when the term of the triumvirate expired on December 31, 33 BCE. While again the triumvirs did not abdicate their power, the consuls for the new year decided to try and exert their power and move against Octavian. He forced them to flee Rome and head east to Antony. They were followed by many senators, allowing Antony to form a counter-Senate in the East. Antony also divorced Octavia, formally breaking with Octavian and making it appear that he accepted his new role as an eastern king alongside Cleopatra.

Octavian reinforced this idea by opening the will that Mark Antony had lodged with the Vestal Virgins. Whether what Octavian reported was inside the will was true or not is questionable, but he alleged that Antony planned to be buried in Alexandria, to recognize Caesar’s son by Cleopatra, Caesarian, and to leave Roman lands to his children with Cleopatra. This was enough to win over public support. Octavian had a civil oath made to his person. This allowed him to declare war on Cleopatra in the name of Rome and strip Antony of his formal powers and position.

The war began in earnest in 31 BCE, with Agrippa launching surprise attacks on Antony’s Greek harbors, cutting off his supply lines. Octavian and Agrippa had a decisive victory at the Battle of Actium on September 2, 31 BCE. Antony and Cleopatra fled back to Egypt while most of their forces surrendered to Octavian. Many eastern client kings followed suit and defected. Octavian marched into Egypt, ostensibly ready to negotiate, but both Antony and Cleopatra chose suicide.

The final defeat of Mark Antony left Octavian unchallenged as the most powerful man in the Roman world, with his triumviral powers intact. He spent the next four decades establishing a way to formalize his absolute power in Rome within the trappings of the Republic that the Roman elite still clung to. He was again granted imperium maius in 19 BCE, received tribunicia potestas (tribunician power) in 23 BCE, and eventually became pontifex maximus in 12 BCE following the death of Lepidus. In many ways, this was the final piece of the puzzle of his patchwork of powers which enabled him to become pater patriae (father of his country) in 2 BCE.

But importantly, he had sufficient personal auctoritas in 27 BCE that he could finally abdicate his triumviral powers. This was also the year he was granted the name Augustus, which singled out his central, integral, and indispensable role in the new Roman state. The year 27 BCE is generally chosen for dating the official start of the imperial period in Rome.