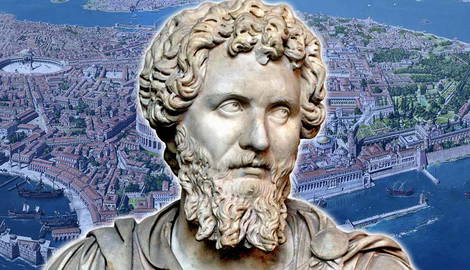

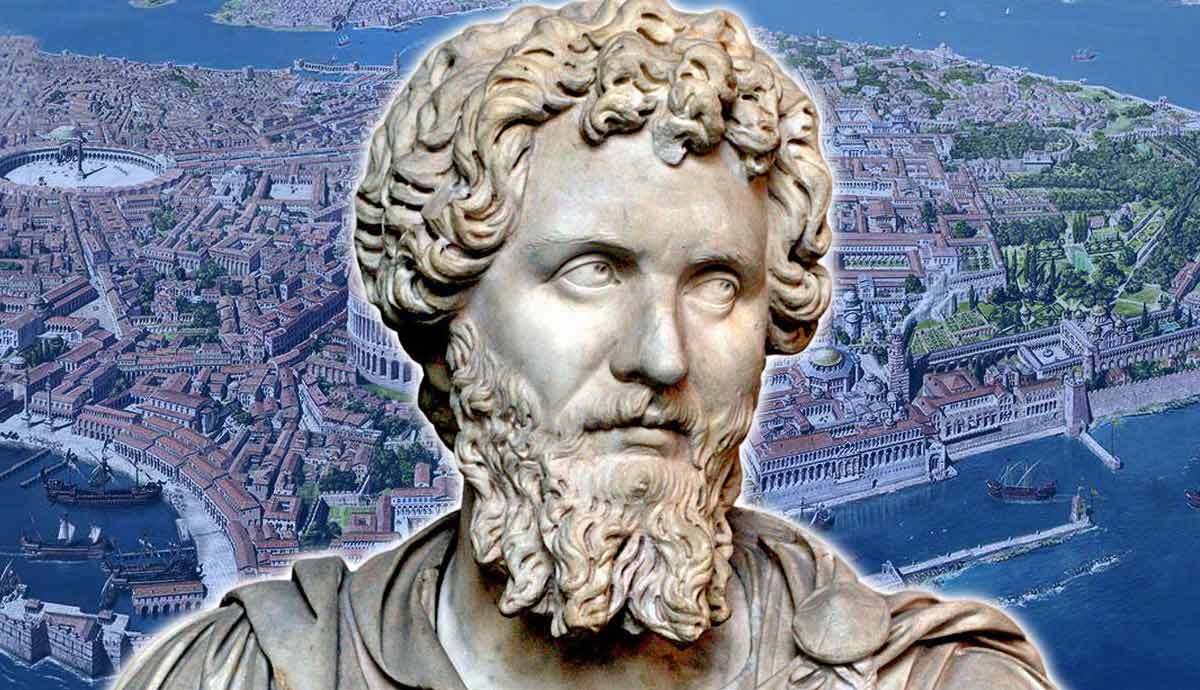

Septimius Severus besieged the city of Byzantium in 193 CE and destroyed it after two years of siege. Being moved by his son, Caracalla, he seems to have later rebuilt it. According to some sources, he greatly restored it, building different monuments throughout the city, such as a new Hippodrome. Over a century later, Constantine picked Byzantium as the site of his new capital, which he called Constantinople. Septimius Severus’ siege of the city and its subsequent reconstruction have often been overlooked regarding Constantine’s choice. We will try to understand the impact this siege had on the city and Constantine’s choice.

Historical Context

In 192 CE, the emperor Commodus was assassinated, which introduced what would later be known as the Year of the Five Emperors. During this time, Septimius Severus, later to be the first African Roman emperor, fought against his rivals to become emperor.

First, he fought Didius Julianus, the man who had bought the throne from the Praetorian Guard. Then, he moved against another rival, Pescennius Niger, who had declared himself emperor with the help of his legions in Syria. Severus sent his troops to besiege the city of Byzantium, which had sided with Niger, while he chased him across Asia Minor. Severus defeated Niger at the Battle of Issus in 194 CE and killed him. According to Cassius Dio, Niger’s head was presented to the defenders of Byzantium, who were still holding out and would do so for another two years (Harris 2007, p. 44).

After beating Niger, Severus went west and defeated Clodius Albinus at the Battle of Lugdunum, which was the largest battle in Roman history.

Septimius Severus’ Siege of Byzantium

Multiple ancient sources describe the siege of Byzantium. Herodian, a historian writing in the 3rd century CE and a contemporary to the events described, describes the siege as follows:

“Severus, in the meantime, pressed on with his army at top speed, halting for neither rest nor refreshment. Having learned that Byzantium, which he knew was defended by the strongest of city walls […] He also sent troops to continue the siege of Byzantium, which was still under blockade because the soldiers of Niger had fled there. At a later date Byzantium was captured as a result of famine, and the entire city was razed. Stripped of its theaters and baths and, indeed, of all adornments, the city, now only a village, was given to the Perinthians to be subject to them” – 3.2.1 & 3.6.9.

We can see in this passage that the city of Byzantium was perceived by Herodian as a formidable city with constructions such as theaters and baths, and guarded by strong walls.

Septimius Severus besieged the city for over two years. It surrendered not because of a direct strike, but only after food ran out due to Severus’ ships intercepting Byzantine vessels and destroying them (Harris 2007, p. 45). This shows that the city had considerable defenses even at this time.

Rebuilding Byzantium

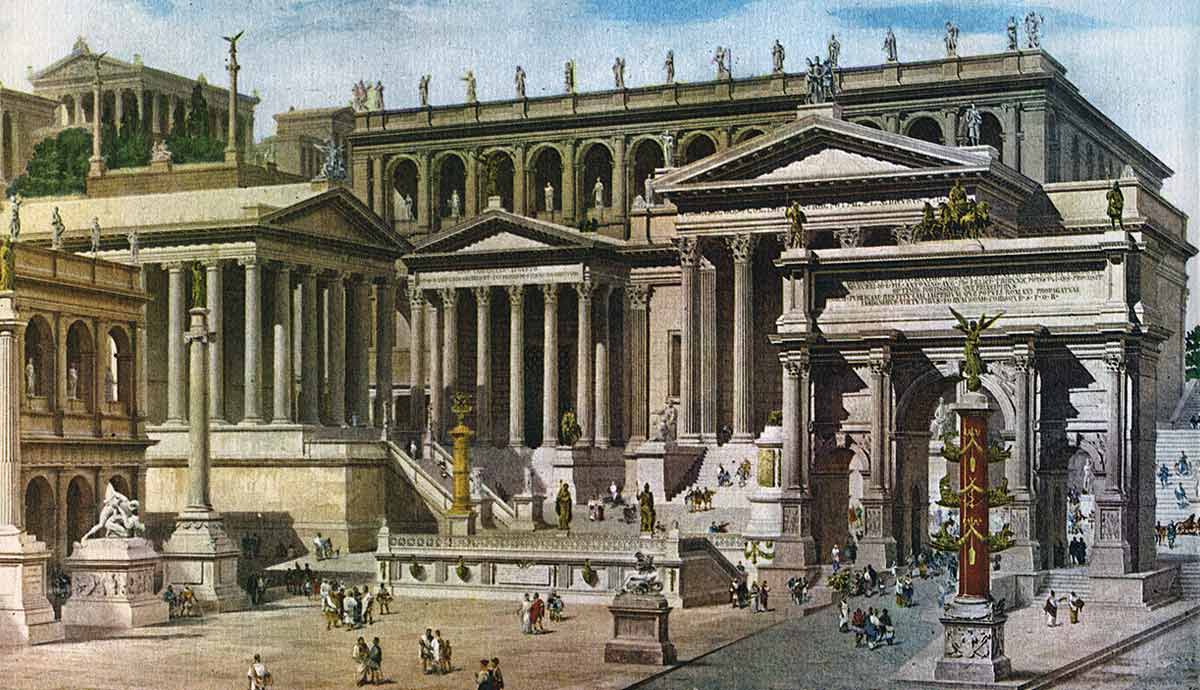

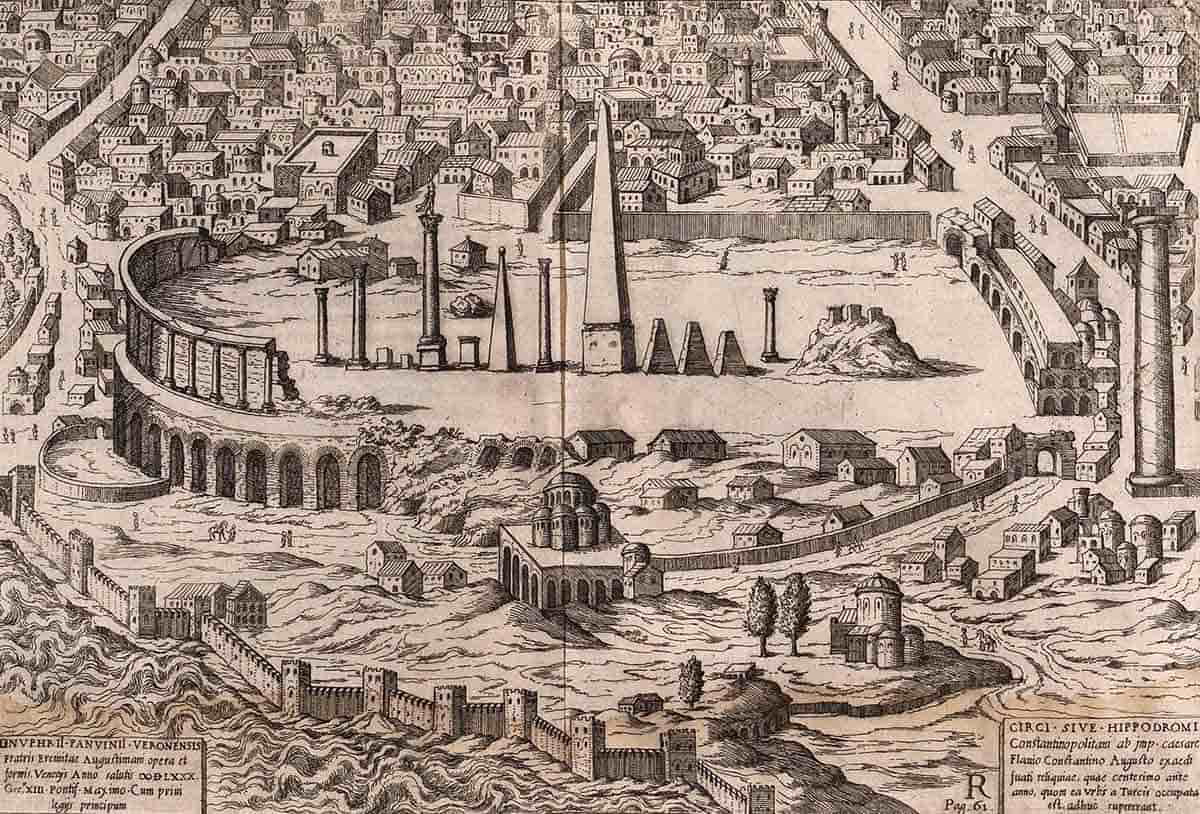

After stripping the city of its freedom and destroying some of its buildings, Severus decided not only to rebuild Byzantium, but to embellish it. He was probably moved by his son Caracalla, as the Historia Augusta informs us. This is confirmed by coins which show that Caracalla held a magistracy in Byzantium between 202 and 205 CE (Russell 2017, p. 220). He furbished it with new constructions, such as expanded walls and a Hippodrome in 203 CE, which was later developed by Constantine. Some scholars have debated whether Severus really built the Hippodrome or if it was only Constantine, but historian Engin Akyürek has demonstrated that Severus did start the construction of the Hippodrome, and Constantine either finished it or expanded it (Akyürek 2021, p. 8).

Severus built the Baths of Zeuxippus and an amphitheater. The city was also renamed Colonia Antonia in honor of his son Caracalla (Antoninus was his real name). The new plan of the city was centered around a tetrastoon, a square enclosed by four porticoes (Janin 1964, p. 16). He also greatly refurbished existing buildings, including a theater, the docks, and multiple temples.

Septimius Severus issued coins showing him as the new founder and protector of the city. He seems to have wanted to channel the second “founder” of the city, Pausanias, who lived in the 5th century BCE. The number of renovations and constructions attributed to Severus has been put in question by scholars. They argue that the literary sources that describe Severus’ reconstruction all date from the 6th century CE and exaggerate (Pont 2010).

Between Severus’ destruction and Constantine’s foundation of Constantinople, the Historia Augusta mentions that the troops of Emperor Gallienus razed the city to the ground. This information is contradicted by a later historian, Zosimus, who writes that Constantine found the city already furnished with buildings. The Historia Augusta is the only source that tells us this.

But How True is Severus’ Reconstruction?

Around the year 500, there was an attempt made by certain conservative Roman writers to rewrite the ancient history of Byzantium, now Constantinople. The goal was to anchor the city’s past in Roman times.

They needed a Roman founder who exemplified traditional Roman values, something that Constantine lacked (Mango 2003, p. 594). We know, through coins and the Historia Augusta, that the city of Byzantium was more affectionate towards Caracalla than his father. Mango argues that the walls of the city were constructed at least 20 years after the death of Severus, and before the attack from the Goths in 258 CE (Mango 2003, p. 596).

Unfortunately, archaeology has not helped in dating the construction of different sites. Archaeological digs have been carried out under the hippodrome and the Baths of Zeuxippus, but they have not given us sufficient results. What we know from literary sources, though, is that during the 3rd century, the city of Byzantium grew in size and importance. For instance, multiple emperors, such as Caracalla, Macrinus, Valerian, Aurelian, and Diocletian, all passed by the city with their armies and nobles, and some even prescribed laws (Aurelian and Diocletian in particular—see Mango 2003, p. 607), which demonstrate the importance and size of the city during this century. This also seems to contradict the claim that Gallienus’ forces razed it to the ground.

Without more concrete archaeological results, we must conclude, like Mango, that we should be skeptical of Severus’ reconstruction of Byzantium.

Constantine’s Choice for a New Capital

Contrary to popular belief, Byzantium had been a site of importance for centuries. For instance, Trajan, writing to Pliny the Younger in the 2nd century CE, described the city as follows:

“It is owing to the situation of the free city of Byzantium, and the fact that so many travelers make their way into it from all sides, that, in conformity with established precedent, I have decided to send them a legionary centurion to protect their privileges.”

Even though it was not one of the biggest cities in the empire, it was a considerable site in the 2nd century CE. We have already mentioned its growing importance during the 3rd century CE.

Constantine, the first Christian emperor, picked the city for his new capital, Constantinople, because of its strategic location, which, as we have seen, was tested over a century earlier during Septimius Severus’ siege. A later writer, Zosimus, explains that Constantine picked Byzantium because of its location, but mentions only briefly the siege of Severus:

“Afterwards changing his purpose, he left his work unfinished, and went to Byzantium, where he admired the situation of the place, and therefore resolved, when he had considerably enlarged it, to make it a residence worthy of an emperor. The city stands on a rising ground, which is part of the isthmus enclosed on each side by the Golden Horn and Propontis, two arms of the sea. It had formerly a gate, at the end of the porticos, which the emperor Severus built after he was reconciled to the Byzantines, who had provoked his resentment by admitting his enemy Niger into their city.” – New History, 2.30.2.

If we follow Zosimus, Severus’ siege seems not to have been of great importance to Constantine.

But, when Constantine founded his new capital, he also placed himself as the latest in a triad of founders, Byzas, Pausanias, Severus, and now himself. He seems, therefore, to have not only been aware of but also pushed Severus’ claim of being the third founder (Russell 2017, p. 220).

In a foreshadowing passage, Cassius Dio, writing in the early 3rd century CE, describes the site as follows:

“Their city is most favorably situated in relation both to the two continents and to the sea that lies between them, and possesses strong defenses both in the lie of the land and in the nature of the Bosporus. For the city is built on high ground and juts out into the sea […] In a word, the Bosporus is of the greatest advantage to the inhabitants; for it is absolutely inevitable that, once anyone gets into its current, he will be cast up on the land in spite of himself. This is a condition most satisfactory to friends, but most embarrassing to enemies.” – Epitome of book LXXV, 10.

If we imagine Constantine reading writers such as Cassius Dio and him being aware of Severus’ claim of following in the footsteps of Pausanias, it seems likely that Septimius Severus’ siege of Byzantium was an inspiration to Constantine. At the very least, we must deconstruct the popular belief that Constantine found Byzantium a small village. From the reign of Trajan at least, the city had had a growing importance, even if we remove the supposed reconstructions made by Severus.

Bibliography

- E. Akyürek, The Hippodrome of Constantinople, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2021.

- J. Harris, Constantinople: Capital of Byzantium, London, Continuum, 2007.

- R. Janin, Constantinople byzantine : Développement urbain et répertoire topographique. Deuxième édition, Paris, Institut français d’études byzantines, 1964.

- C. Mango, « Septime Sévère à Byzance », Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 147 (2003), p. 593-608.

- A.-V. Pont, « Septime Sévère à Byzance : L’invention d’un fondateur », AnTard, 18 (2010), p. 191-198.

- T. Russell, « Before Constantinople », The Cambridge Companion to Constantinople, ed. S. Bassett, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2022, pp. 17-32.

- T. Russell, Byzantium and the Bosporus: A Historical Study, from the Seventh Century BC until the Foundation of Constantinople, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2017.