Humans have always been fascinated with color and its transformations. Starting from earth pigments at the dawn of humankind, they moved to experimenting with minerals, organic substances, and even synthetic materials to create new tones to use in art and design. Some of these rare and desirable hues were made from weird or even dangerous substances. Read on to get familiar with the strangest colors in art history.

1. Mummy Brown

The discovery of Ancient Egyptian mummies triggered a strange obsession with dead bodies in the West. For a while, the mummified remains were believed to have medicinal qualities and used to heal bruises or relieve a toothache. The origins of this idea were traced back to a mistake in the translation of an Arabic text on the properties of bitumen, which was used in traditional Persian medicine. At the time, apothecary owners, who also supplied artists with pigments, discovered that ground mummies also produce a rich purple-brown color that could be used for painting.

The sudden increase in demand for mummies had a dramatic effect on the Egyptian archaeological sites. Eager to earn money on the Western craze, locals broke into tombs and burial sites to steal dead bodies. Some pigment merchants tried to forge the pigment using locally sourced animal bodies. However, by the beginning of the 20th century, the demand for mummies had waned, as newly discovered and synthesized pigments proved to be more durable. The famous Pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones claimed to ceremoniously bury his tube of mummy brown paint after learning the origins of the hue.

2. Indian Yellow

One of the most famous stories about pigments concerns the Indian Yellow—a bright yellow pigment extensively used in Indian art. In the 17th century, it was imported to Europe and used by many famous artists, including Johannes Vermeer. In its raw form, the pigment had a distinctive odour that suggested its origin. For a while, the process behind the Indian Yellow production remained a mystery to Westerners until the colonial authorities in India conducted research on the local pigment industry.

According to the most popular version of the story about the pigment’s origin, Indian Yellow was made from evaporated cow urine. To achieve the bright yellow tone, the keepers forcefully fed the cows mango leaves. Such a diet had a detrimental effect on the animals’ health and was banned at some point. The role of cows in pigment products was long believed to be a hoax, but was proved after extensive chemical analysis in the 2010s. Today, Indian Yellow is produced synthetically. Compared to its natural alternative, lab-made Indian Yellow does not fade when exposed to sunlight and, thankfully, is devoid of any unnecessary smells.

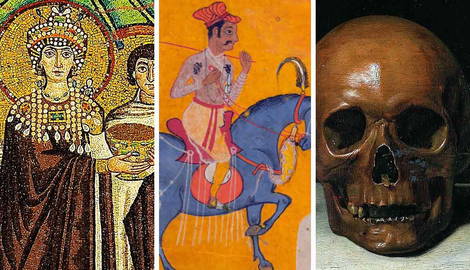

3. Tyrian Purple & Tekhelet

In Egyptian and Roman Antiquity, the color purple was considered to be a royal hue, reserved only for the upper class due to its complex way of production. The bright pigment, known as Tyrian purple, was enormously expensive, as it was produced from crushed and boiled predatory sea snails from the Murucidae family. To dye 2 pounds of wool fabric, divers had to collect more than 30,000 molluscs. One part of the dye was evaluated at three parts of gold, making it completely unavailable to anyone who did not belong to the ruling class. What is worse, artisans used urine to treat the dyed fabric so the paint would not fade too soon. So, the most prestigious of colors may have had a royal hue, but also a terrible stench.

A similar species of shellfish was used in the Middle East to produce a pigment known as tekhelet—a sky-blue color used in Jewish tradition for rituals and priests’ garments. In the 7th century CE, the technology for producing tekhelet-based dye was lost due to the Muslim conquest of the Levant, but was revived through experiments in the Modern era. In a similar manner, artisans used crushed bugs to produce red pigments like carmine or kermes.

4. Scheele’s Green

Today, the color green is associated with something natural, organic, and generally beneficial for your health. However, this was not the case two centuries ago, when green was associated with fashionable yet highly toxic substances that could kill you. Generally, vivid green dye was a challenge for artists and fabric manufacturers, as natural and mineral pigments only produced dark colors that tended to fade quickly and transform into earth tones. It all changed in 1775 when German chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele discovered a formula of arsenic-based dye that produced an incredibly bright and vivid green tone.

Arsenic was known to be a highly toxic material, but it did not stop Scheele’s contemporaries from embarking on the new fashion trend. Dresses, household items, and even children’s toys and desserts were made with arsenic-based dye. Those who suffered most were underprivileged women and children who worked in dye shops and were exposed to large amounts of arsenic. They were covered in painful sores, they lost hair and teeth, and died within months of starting a job. Despite all these factors, the production ceased only in the late 19th century, when non-toxic green dyes replaced the trendy arsenic hue.

5. Vermillion

The intense red hue of vermilion comes from a high amount of mercury, making it one of the most desirable yet toxic pigments in the history of mankind. Depending on the inclusions and soil composition in particular areas of extraction, Vermillion red can have pink or orange undertones. It was in such high demand with artists and artisans that some fraudulent merchants attempted to forge it by selling crushed red brick instead. For that reason, artists recommended their students buy vermilion red in the form of crystals, even if it was more expensive.

In his Theory of Colors, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe called vermilion a highly energetic yet violent color that appealed to active and rather brutal people. Particularly, he believed this blood-like tone pleased children and the so-called savage peoples, with their uncivilized perception unspoiled by society.

Over time, vermilion tends to darken and turn brown-black. The toxicity of mercury was underrated for too long, causing many artisans to die from exposure. Today, museum curators keep objects that include vermilion away from sources of light and heat to avoid activating the toxic properties of the material.

6. Radium Green

The story of toxic green dyes, unfortunately, was not over with arsenic-based Scheele hue. In 1898, scientists discovered radium—a glowing, greenish substance that was then promoted as a miraculous component for makeup, facial creams, and even food supplements. Manufacturers promised their clients a “natural healthy glow,” still unaware (at least partially) of the dangerous effects of radiation.

During World War I, radium-based paint was used to paint watch dials and hands so they would glow in the dark. The watch companies employed mostly young women who were able to perform a meticulous and attention-requiring task. To achieve extra fine lines, they used camel hair brushes and often licked them to stick the bristles together, ingesting radium.

Moreover, impressed by the glow of their work material, some women painted their nails and did makeup using radium-based paint. In the early 1920s, a group of employees developed acute symptoms of radiation poisoning, including bone necrosis, causing their jaws to literally fall off their faces. To avoid accusations, their employees claimed that women were carriers of venereal diseases and suffered from syphilis rather than toxic substance exposure. However, after extensive research, the use of radium in industries was severely limited, and new safety regulations were installed.

7. Lead White

Lead white, produced from chemical reactions of lead, vinegar, and horse dung, was one of the most notoriously toxic yet popular pigments used not only in art but also in makeup. It is one of the oldest synthetic pigments that was produced in 300 BCE. As a cosmetic product, lead was celebrated for giving a pale “aristocratic” skin tone. However, over time, lead would become poisonous to the wearer’s skin, leaving sores and damaging the skin texture, thus forcing them to apply even more of the substance.

Lead and other components of the pigment led to irreversible brain damage and the rapid development of symptoms like rotting teeth, fits of anger, and loss of mental activity. Lead white paint is also believed to be the main cause of Caravaggio’s difficult character and criminal behavior. A notoriously messy painter, Caravaggio covered himself in paint almost head to toe while working and most likely had chronic heavy metal poisoning.

Today, the production and use of lead white in its original form is banned or at least strictly limited in most countries. However, the presence of lead in pigments allows art historians to study the transformation of paint colors over time, as it reacts to other components used in paintings.