Explore what defines the “sublime” through a dedicated study of one of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio’s most famous works, The Calling of St. Matthew, in conjunction with the earliest definitions of the sublime by Longinus. Through an analysis of the sublime and Caravaggio’s work, you’ll see the traits that outline the loose definition of the sublime in art history.

Who Was Caravaggio?

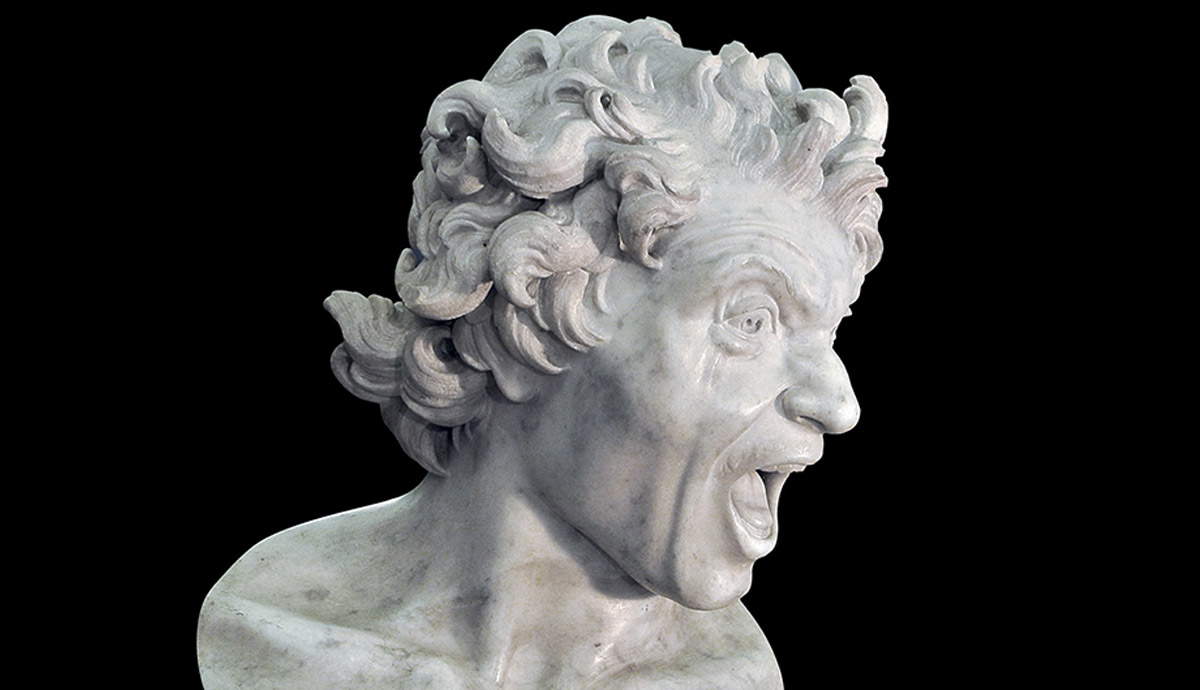

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio was born in 1571 in Milan. Known simply as Caravaggio, the Baroque master has become a household name throughout this century, and his talents have inspired and attracted a new generation of art lovers. His art evokes strong emotions in his audiences and can make us question the very fabric of what it means to be a Christian. Caravaggio questioned the status quo of the art that came before him, during the Renaissance and reasserted his idea of natural beauty.

Caravaggio had a notoriously dramatic life. Starting in the village of Caravaggio, a small town within the area of Milan, the young artist lost both his grandfather and father on the same day to illness. Later in his tumultuous life, Caravaggio killed a gentleman with whom he had quarreled in the streets of Rome and was subsequently forced to flee for his life. Throughout his short and turbulent life, Caravaggio created an oeuvre that broke the mold of what individuals thought of as sacred art.

Longinus On the Sublime

The sublime is no one single thing — it comes in various shades and hues and differs with each object, rendering it both alluring and impossible to describe. In that aspect, the sublime is similar to the definition of beauty: it is in the eyes of the beholder, and thus, only the beholder can define what it means.

The Greek origins of the concept of the sublime come to us from the author known as “Longinus.” Quotations are around his name, as the actual author is unknown, and truth be told, the concept of the sublime goes back further than Longinus in the 1st century CE.

When Longinus set out his treatise on the sublime, he wrote about the sublime in rhetoric or the written word, not art. However, there are crossovers between the two. Longinus set out five sources of the sublime:

1) Felicitous boldness in the thoughts

2) Capacity of intense and enthusiastic passion

3) Skillful molding of figures — sentiment and language

4) Noble and graceful manner of expression

5) Embrace of dignity and grandeur

These five sources, or examples of the sublime, help audiences understand how to properly define it. However, the sublime could be perceived as adapting to each individual; what one person describes as sublime might not be for another, and so on.

The beauty of the sublime is its individualistic quality, and yet at the same time, it appears to bring together ideas into a singular moment of divine encounter, whatever the divine represents for an individual. This article will look into a few of Longinus’s sources of the sublime as they relate to Caravaggio’s artwork.

The Calling of St. Matthew and the Sublime

The author of The Sublime, Longinus, was preoccupied with the expressive power that could result from the narrative effect. The Baroque master, Caravaggio, also appeared preoccupied with this notion, as many of his paintings seem to consist of a narrative coupled with profound emotions.

The Calling of St. Matthew, one of Caravaggio’s most famous works, lures the viewer in with the story and captures the viewer’s attention through the subtle movements within the painting. The pointing of Christ’s finger, the grasping of the coins, and St. Matthew’s doubtful expression intertwine with the larger narrative concept of the story of the tax collector who became a disciple. Longinus provided his example of emotive power through narration in The Sublime, citing God’s power: “God said, Let there be light, and there was light. Let the earth be, and the earth was.”

The Gospel of Matthew states, “As Jesus went on from there, he saw a man named Matthew sitting. ‘Follow me,’ he told him, and Matthew got up and followed him.” Caravaggio took Christ’s command of “Follow me” and visually transformed it into a simple yet powerful gesture of expressive power, which is witnessed in Christ’s hand as he points towards Matthew.

For Caravaggio, it could be presumed that he had adhered to Longinus’s advice to narrators, and by extension to Baroque artists, to be bold and original; too much luxury, as Longinus noted, may lead to decay in eloquence, essentially confusing a simple and powerful message with extraneous details. It could be reasoned that Caravaggio’s lack of luxury in this painting informed the artist’s realistic qualities in the rest of his oeuvre.

Sublime Qualities: Light and Passion

One of Caravaggio’s earliest biographers noted the artist’s use of individuals he met or saw on the street and employed as models. Caravaggio’s preference for avoiding luxury with his choice of nonprofessional models is significant. To maintain what was pertinent, Caravaggio stripped down any overwhelming aspect of wealth and allowed the narrative to inspire the visual form. For Caravaggio, this was demonstrated through his reductiveness, illumination, and focus.

The Calling of St. Matthew is still in situ at San Luigi dei Francesi, the French National Church in Rome. This is beneficial for visitors today, as one can envision what it must have felt like to see the painting when it was first revealed. The viewer can, in this way, gain a sense of the immensity and drama of the painting.

This composition’s use of light also connects it to the notion of the sublime. The effect comes through the sensation of St. Matthew being called from sinner to saint, as the light illuminates Matthew while Christ remains partially in the dark. The halo that Christ wears is noticeably highlighted, yet what is most illuminated is the hand of Christ that is pointed directly toward Matthew, beckoning him to follow Christ.

This very light focuses primarily and unapologetically on Matthew as if saying, “Yes, you, the sinner, are just who we need for this mission.” Perhaps this sent a message to the ordinary, everyday Christian. Caravaggio reminded the people that God is paying attention and may call on them at any given time — one must be ready to be of use to God. It may have been hoped that through Matthew’s transfiguration, the viewer would be transformed as well.

Longinus argues that the sublime requires intense and enthusiastic passion. Although it may seem challenging to perceive passionate enthusiasm in the dimly lit, tavern-like setting, an example can be found under the table where Matthew and his companions are seated.

Upon closer observation, it becomes apparent that as Matthew questions himself with a gesture, he simultaneously turns his legs toward Christ and St. Peter, almost as if he is in the process of rising from his seat. It seems he has already accepted the request and is eagerly shedding his past life to join Christ and become his disciple. This anticipated movement by Matthew, as he abandons his unrighteous occupation as a tax collector to follow Christ, serves as a powerful reflection of the inner greatness of the soul.

Caravaggio’s masterpiece, The Calling of St. Matthew, exemplifies the sublime through its emotive power and narrative effect, capturing the essence of Longinus’s concept of the sublime in art. The artist’s ability to convey a profound story and evoke intense emotions within the viewer aligns with Longinus’s principles, showcasing how the sublime transcends time and medium to create a truly divine encounter for each individual. Caravaggio’s work continues to inspire and provoke contemplation, solidifying his place as a pivotal figure of the sublime within art history.