A member of the Bagrationi Dynasty that ruled Georgia for a thousand years, King Tamar the Great’s reign (1184-1213) marked the zenith of Georgia’s Golden Age. The first female monarch in Georgian history, Tamar skillfully overcame opposition among her nobles to consolidate her power. She then launched a series of victorious military campaigns that consolidated Georgia’s dominance of the Caucasus. The renown of Tamar’s cosmopolitan court at Tbilisi spread far and wide, and she continues to be remembered by Georgians as an ideal ruler.

Tamar the Great: A Golden Inheritance

Georgia’s Golden Age was inaugurated in the late 11th century by King David IV, also known as David the Builder, for his efforts in reuniting the country. When David succeeded to the throne in 1089, his power was limited to Western Georgia. The rest of historical Georgia, including the ancient capitals of Mtskheta and Tbilisi, were under the control of Muslim vassals of the Seljuk Turks.

After consolidating power internally in the 1090s, David took advantage of the Muslim powers’ preoccupation with defending the Holy Land during the First Crusade to reunite most of Georgia by 1105. Several fortresses remained under Seljuk control, and it was only after defeating the Seljuks at the Battle of Didgori in 1121 that David was able to regain Tbilisi and transfer his capital there.

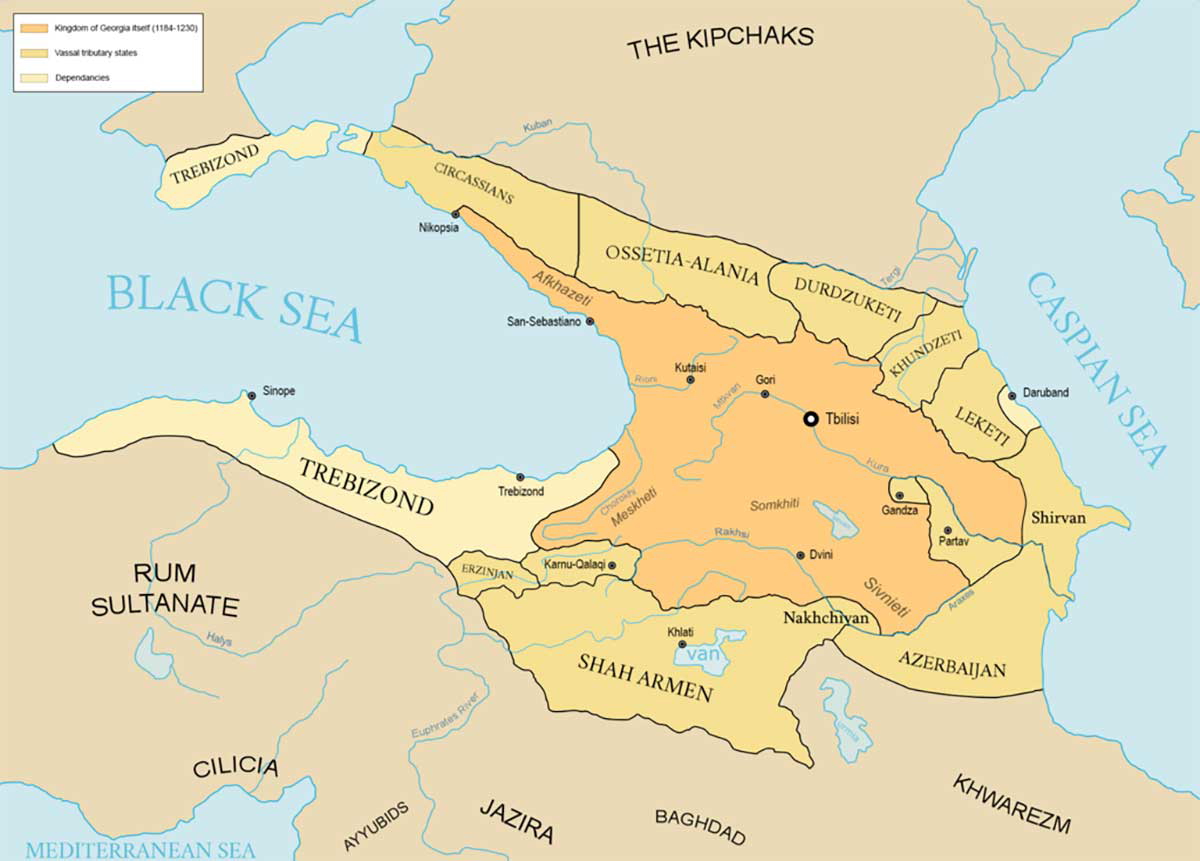

Victory at Didgori allowed the Georgians to dominate the southern Caucasus for a century, and David was also recognized as King of Armenia. The conquest of the emirate of Shirvan in present-day Azerbaijan brought Persian influences to the Georgian court.

Upon his death in 1125, David was succeeded by his eldest son, Demetre. Demetre spent much of his reign struggling to defend his realm from various Muslim threats on the southern frontier, including the loss of Armenia. In 1155, Demetre was dethroned by his son David V, who was poisoned within a few months. While David left behind a young son, he was succeeded by his younger brother, Giorgi III.

During the 1160s and 1170s, King Giorgi launched several military campaigns which restored Armenia to Georgian rule. In 1177, Giorgi put down a rebellion by his commander Ivane Orbeli, who sought to place David V’s son Demna on the throne. The brutal punishment inflicted on Demna claimed his life.

A Female King

After putting down the Orbeli rebellion, King Giorgi took steps to secure the succession for his progeny. While Giorgi had no sons, he had two daughters with his wife, Queen Burdukhan. In 1178, Giorgi arranged to crown his eldest daughter Tamar as his co-ruler.

The 18-year-old Tamar was recognized as mepe, the title held by previous (male) kings of Georgia. While Tamar is often called a queen in other languages, the Georgian word dedopali is used for a queen consort. Although Tamar is occasionally referred to as dedopali in the historical record, she is more frequently known as mepe or king, making her one of the few female kings in world history.

Tamar’s coronation at the ancient cave citadel of Uplistsikhe as her father’s co-ruler was intended to affirm her status as Giorgi III’s heir. When Giorgi died in 1184, the Georgian nobility insisted on a second coronation for Tamar at the Gelati Monastery in Kutaisi.

While Tamar acquiesced to noble demands for the dismissal of low-born ministers appointed by her father, she resisted efforts to establish a permanent noble council with the sole right to appoint ministers and enact laws. She arrested the rebel leader Qutlu Arslan but released him in a show of magnanimity. Over time, she would gain political confidence and govern her realm with the support of a circle of loyal ministers.

An Ill-Fated Marriage

Although Tamar herself was reluctant to do so, her council insisted that she should marry the Rus’ prince Yury Bogolyubsky. Yury’s father, Andrey Bogolyubsky, sacked Kyiv and dominated the Rus’ principalities from the city of Vladimir on the Klyazma River to the east of Moscow. After his father’s assassination in 1175, Yury became a fugitive and formed an alliance with the Kipchaks (Polovtsians) in the Northern Caucasus to restore his throne.

In 1185, Yury married Tamar and was given the title of mepe, though Tamar held the higher title of mepeta mepe (king of kings). Known as Giorgi Rusi (George of Rus’) in Georgia, Yury led victorious expeditions in Armenia and Shirvan. Tamar usually accompanied her armies as they set off on campaign but stopped at the last church on Georgian soil. Despite Yury’s military prowess, Tamar was not enamored with him and found him a drunkard and a brute. She received permission to divorce him in 1187.

While Yury was exiled to Constantinople laden with gold and jewels, in 1189 Tamar married David Soslan, an Ossetian prince closely related to the Bagrationi dynasty. In 1191, rebel lords from southern Georgia unexpectedly installed Yury on the throne in Kutaisi. After recovering from the initial shock, Tamar mobilized loyal armies to defeat the rebels. In her magnanimity, she spared her ex-husband and sent him back to Constantinople. Yury made another attempt to reclaim the throne with the support of Azeri lords in 1193 but was quickly defeated.

Military Conquests

With the troublesome Yury out of the way, Tamar and David could look towards expansion and acquiring new glory. In 1192, the couple welcomed the birth of a son named Giorgi with a victory over Abu Bakr, Atabeg of Azerbaijan, which once again made Shirvan a Georgian vassal. David Soslan followed with an impressive win over Abu Bakr at Shamkor in 1195. This enabled the Georgians to occupy the important cultural center of Ganja. Though Abu Bakr soon retook Ganja, Georgian forces captured the trading town of Nakhichevan in 1197, expanding Tamar’s influence into northern Persia.

In the meantime, the talented Georgian general Ivan Mkhargrdzeli (whose brother Zakaria was Tamar’s chancellor) led successful campaigns to regain a host of Armenian cities from their Muslim rulers. These victories set Georgia on a collision course with Rukn ad-Din, an ambitious warrior who had recently overthrown his brother to become Sultan of Rum (the Seljuk state in central Turkey).

After retaking Erzurum from Georgia in 1201, Rukn ad-Din assembled a large army and dispatched an envoy to Tbilisi with what he believed was a gracious diplomatic offer to spare Tamar’s subjects if they surrendered to him. If Tamar were to convert to Islam, he would happily make her his wife; if she refused, she would be his concubine.

Zakaria Mkhargrdzeli responded to the insolent message by knocking the envoy to the floor with a single punch. In her reply, Tamar informed Rukn ad-Din that the Georgian army was already at his gates. The two armies met at Basiani near Erzurum in around 1202. The Georgians surprised the enemy as Zakaria Mkhargrdzeli threw his vanguard against the enemy center. As Rukn ad-Din organized a counterattack, Georgian flanking units inflicted the decisive blow and put the enemy to flight.

Victory at the Battle of Basiani enabled Georgia to take control of the Turkish fortresses of Erzurum and Kars by 1206. In 1204, Tamar saw another opportunity to strengthen her kingdom’s prospects after the Sack of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade. Tamar had close family links to the Comnenus dynasty, which had occupied the imperial throne for a century until being overthrown in 1185.

Tamar took advantage of the disintegration of the Byzantine Empire by sending Georgian troops to occupy a large strip of land on the southern coast of the Black Sea. She also installed her nephew Alexius Comnenus as ruler of the so-called Empire of Trebizond. This new entity served as a useful buffer to protect Georgia’s western flank.

While Tamar’s husband, David Soslan, died in 1207, Georgian armies continued to enjoy military success under the generalship of the brothers Zakaria and Ivane Mkhargrdzeli and Tamar’s son Giorgi Lasha (George the Resplendent). Between 1208 and 1210, Georgian armies launched a punitive raid into northern Iran, plundering the cities of Tabriz and Qazvin in the process. The outbreak of rebellion in the mountainous regions of northeastern Georgia in 1211 was soon suppressed by Ivane Mkhardgrdzeli, who succeeded his late brother as Tamar’s commander-in-chief.

Tamar of Georgia’s Cultural Achievements

In addition to glorious feats of arms on the battlefield, Tamar’s reign is regarded as the height of Georgian culture. A century earlier, David the Builder had established the Gelati Academy near Kutaisi and the Ikalto Academy near Telavi in the eastern region of Kakheti. The poet Shota Rustaveli may have studied at both institutions. Rustaveli’s epic poem The Knight in the Panther Skin, dating to around 1200, continues to be celebrated not only as Georgia’s national epic but also as a literary creation of international significance.

Inspired by Persian literary tradition, Rustaveli’s epic is a celebration of courtly love. The tale begins at the court of Rostevan, King of Arabia, who, in the absence of a son, names his daughter Tinatin as his co-ruler. Rostevan’s commander-in-chief, Avtandil, is secretly in love with Tinatin. During a hunting expedition, Rostevan and Avtandil encounter a mysterious knight in a panther skin who kills the slaves whom Rostevan sends after him.

Rostevan and Tinatin send Avtandil on a three-year quest to track down the elusive knight and bring him to the Arabian court. A few months short of the deadline, Avtandil finds the knight in a cave accompanied by his faithful servant-girl, Asmat. Avtandil learns that the knight is Tariel, the commander-in-chief of the Indian armies. Tariel is stricken with grief due to his lack of success in finding and rescuing his beloved Nestan-Darejan, the daughter of King Parsadan of India.

While Tariel refuses to accompany Avtandil to Arabia, the latter promises to return to the cave after delivering his report to Rostevan and Tinatin. With Tinatin’s private encouragement, Avtandil defies Rostevan and makes his way back to Tariel’s cave, offering to seek Nestan-Darejan on his friend’s behalf.

With assistance from several parties, Avtandil eventually learns that Nestan-Darejan has been taken captive by the demonic Kadjis. Avtandil, Tariel, and their friend King Nuradin-Pridon of Mulgazanzar assemble their armies to defeat the Kadjis and liberate Nestan-Darejan. The whole party returns to Arabia, where King Rostevan forgives Avtandil and presides over his wedding to Tinatin. They then travel to India to celebrate the union of Tariel and Nestan-Darejan, and the tale ends with a celebration of brotherhood between Avtandil, Tariel, and Pridon.

Rustaveli’s Arabia and India are poetic versions of the Georgian kingdom, while the characters of Tinatin and Nestan-Darejan are evidently inspired by Tamar herself. Likewise, Avtandil, Tariel, and Pridon bring to mind not only Tamar’s husband, David Soslan, but other heroic military commanders who served Tamar with great distinction.

In addition to Rustaveli, other Georgian poets who celebrated Tamar in verse include Ioane Shavteli and Chakhrukhadze, who wrote a collection of poems entitled Tamariani in her honor.

Death and Legacy of Tamar of Georgia

Tamar spent her final years afflicted by a long illness, possibly cancer, and died in Tbilisi in January 1213. She is believed to have been buried at Gelati Monastery, though her tomb has never been found. Another theory suggests that her body was taken to the Monastery of the Cross in Jerusalem, founded by a Georgian monk in the 11th century. The pious Tamar was canonized by the Georgian Orthodox Church shortly after her death.

Tamar’s reign is regarded as the height of Georgia’s Golden Age. Building on the exploits of her great-grandfather David the Builder and her father Giorgi III, she left behind a realm that was the dominant power in the Caucasus, protected by vassal states on all sides, including a rump Byzantine state. Neighboring Muslim rulers cowered in fear before the might of Georgian armies, while the Pope and Crusader states in the Levant appealed to the court in Tbilisi for assistance.

For all the international prestige and renown acquired by Tamar and her court, this glorious period in Georgian history was to come to an abrupt and unexpected end within a decade of her demise. While her son and successor, Giorgi IV, was a capable military leader, his armies were no match for Jebe and Subutai’s Mongol cavalry, who unexpectedly arrived on the scene in 1220-1221 to wreak havoc on the Caucasus and the principalities of Rus’.

The shock of the Mongol invasion marked a definitive end to Georgia’s Golden Age. After being seriously wounded in battle against the Mongols in 1221, Giorgi died in 1223 and was succeeded as mepe (king) by his sister Rusudan. Further depredations by Sultan Jalal al-Din of Khwarazm and a renewed Mongol offensive in 1236 brought subjugation and fragmentation.