The lists of commandments in Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5 are almost identical to each other, diverging significantly only in the reasons they each give for keeping the Sabbath day. This list—often called the Decalogue—is what is popularly known as the Ten Commandments. However, according to the biblical narrative, Moses shattered the tablets upon which this original list had been inscribed when he became angry at the Israelites’ idolatry. In their place, God commanded Moses to make a second set of tablets.

Why Was the First Set of Tablets Destroyed?

The Book of Exodus tells the story of Israel’s escape from Egypt and their subsequent sojourn in the wilderness of Sinai. Upon leaving Egypt, Moses leads the Israelites to the base of a mountain that is called both Sinai and Horeb in the Bible. More importantly, it is identified as the “Mountain of God”—the same mountain where God had appeared to Moses in a burning bush when Moses received his divine call to become Israel’s liberator.

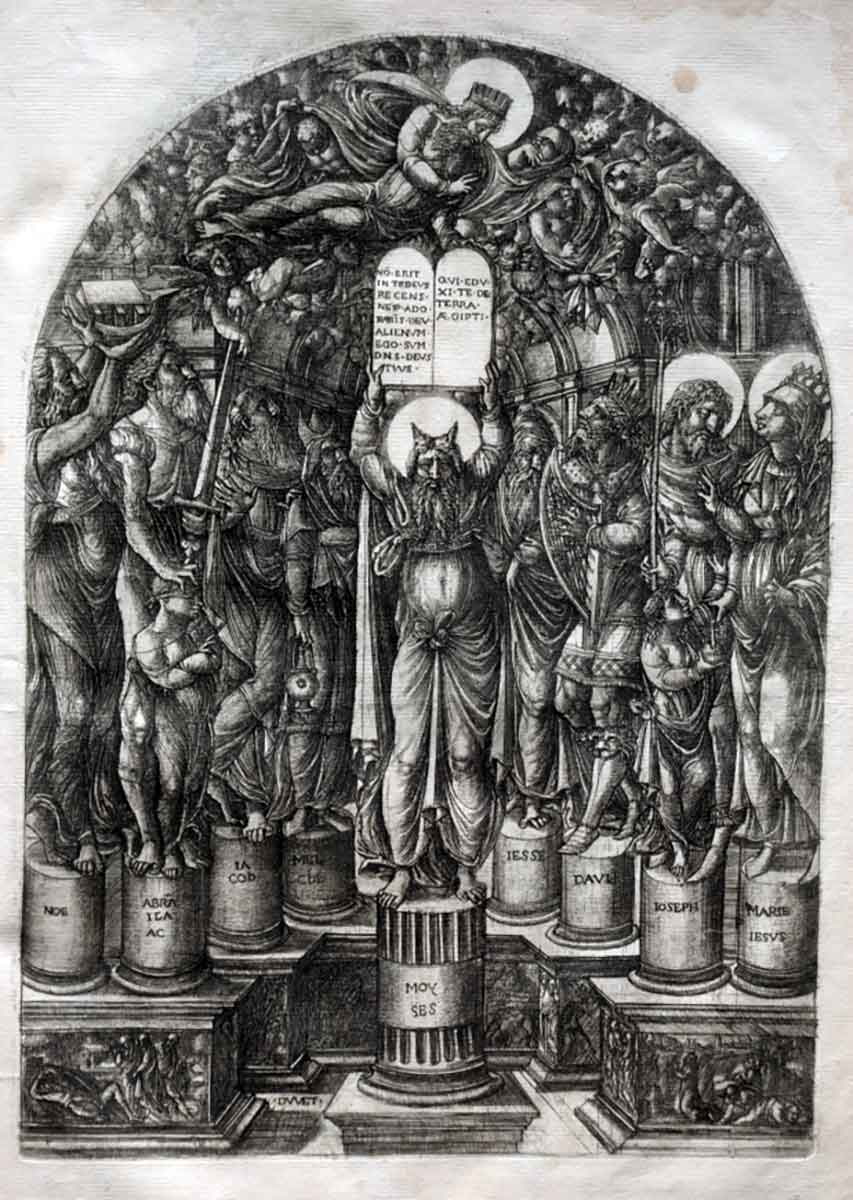

As the story goes, God calls Moses to climb the mountain and, in turn, God would come down and meet him there. There is scarcely a more dramatic scene in the whole Bible. Moses, having ascended out of the Israelites’ sight, spends 40 days amid a cloud of thunder and lightning. Feeling abandoned and terrified at the base of the mountain, the Israelites conclude that Moses must have died. They then pressure Moses’s older brother Aaron to make a golden calf so that they would have an object through which they may worship the God who brought them out of Egypt.

The irony of this scene is not lost on the reader. Before the text explains what was happening at the mountain’s base, the narrator brings his readers to the mountaintop with Moses where the first instructions he receives—which God writes with his own finger on a set of two stone tablets—are the list of commands that are known today in popular culture as “The Ten Commandments.” They begin with: “You shall have no other gods before me. You shall not make for yourself an idol” (NRSVue). When he finally descends from the mountain, Moses discovers the Israelites in a cultic practice forbidden by the divine commands he has just received. In a rage, he shatters the first set of sacred tablets.

What Was on the “Original” Tablets?

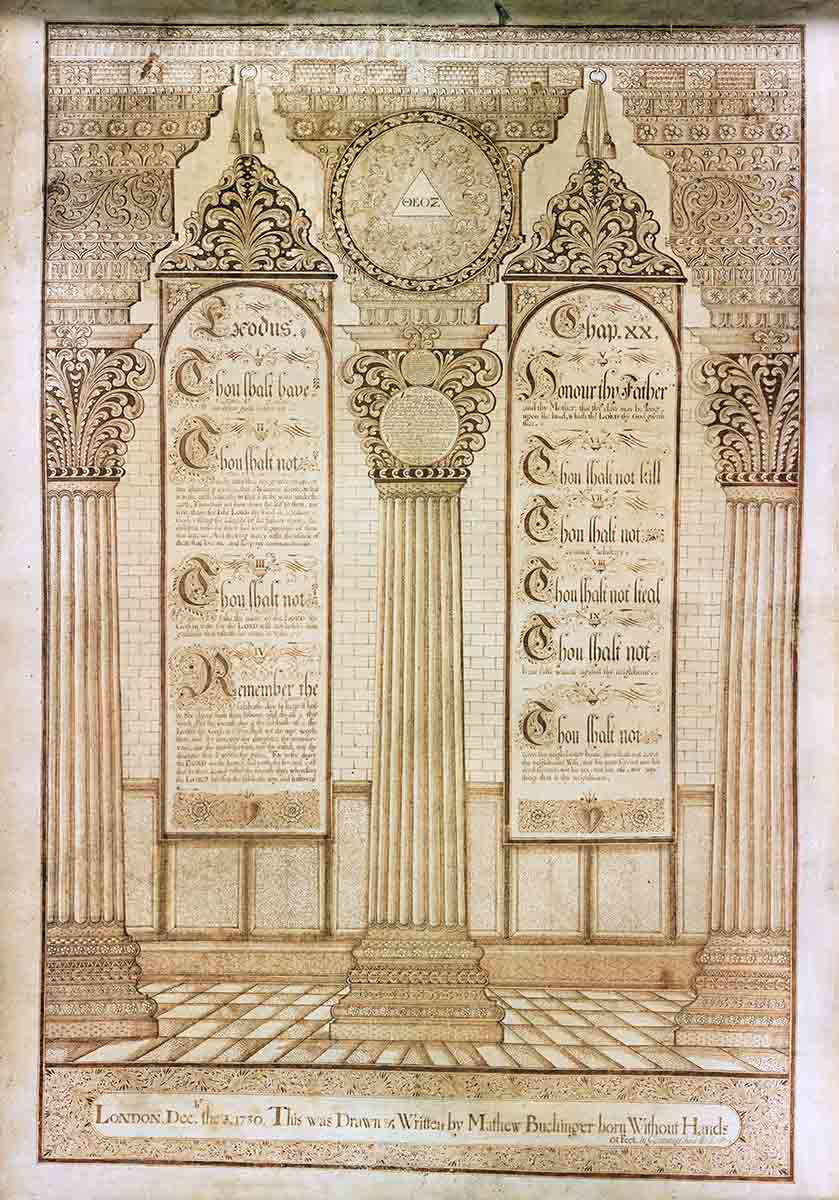

According to Exodus, the original set of stone tablets contained thirteen imperatives. Some are closely related, however, and are combined so that the list reckons at a total of ten. But the numbering can be done in different ways. Specifically, the Sabbath command can be either third or fourth in the list. When it is reckoned as the third, the last commandment against covetousness is divided into two—“You shall not covet your neighbor’s wife” and “You shall not covet your neighbor’s property.” These changes in the numbering, however, do not alter the content of the commandments. The following, thus, is one possible way to order them:

- You shall have no other gods before Yahweh (the name of Israel’s God, rendered “Lord”)

- You shall not make carved images

- You shall not take YHWH’s name in vain

- Remember the Sabbath day and keep it holy

- Honor your father and mother

- You shall not murder

- You shall not commit adultery

- You shall not steal

- You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor

- You shall not covet

The above is a paraphrase of the wording in the biblical text, which is more extensive. This list is found in Deuteronomy as well as Exodus. The wording in each is almost the same, with the only significant difference being the rationale provided for keeping the Sabbath day. In Exodus, the purpose of the Sabbath is to memorialize God’s rest after creation week, spoken of in Genesis. But in Deuteronomy, the Sabbath’s purpose is to remind the Israelites of their past enslavement as a way of encouraging them to be merciful to their own slaves.

But as noted, this is the list that was on the first set of tablets. The Bible presents two possibilities for the second set.

What Is on the Second Set of Tablets?

The Hebrew term translated as the “Ten Commandments” is actually literally rendered “ten words.” For that reason, the more literal “Decalogue” is often used.

Once Moses had broken the first set of tablets, there was a need for another. So, God commands Moses to carve a second pair. But what was written on them? Was it the same as the list that appeared on the first set?

The answer to that question is difficult to discern. On the one hand, both the tenth chapter of Deuteronomy and the first part of Exodus 34 say that, while Moses was to cut the new stone tablets himself, God himself would rewrite the “ten words” even as he had done before. However, beginning in verse ten of Exodus 34, a different set of ten laws appears.

Like the other Decalogue of Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5 (see above), this list also contains more than ten imperatives as well as explanations of the various laws. Still, a list of ten, relatively distinct injunctions is given. They can be summarized as follows:

- You shall not worship other gods besides Yahweh

- You shall not make gods of metal

- You shall give all your firstborn animals to God

- You shall redeem all your firstborn sons (with animal sacrifices)

- You shall keep the Sabbath

- All your males shall observe the three annual festivals

- You shall not offer animal sacrifices with anything containing leaven (yeast or rising agent)

- You shall consume the entire Passover meal

- You shall give the best of the first fruits of your harvests to God

- You shall not boil a young goat in its mother’s milk

Sometimes referred to as the “cultic decalogue” due to its focus on religious life, a straightforward reading of verses 10 through 28 of Exodus 34 implies that these were the laws inscribed on Moses’s second set of tablets!

Are the Ten Commandments About Religion or Morality?

Despite the presence of both within its pages, the cultic decalogue has had negligible influence on cultures that have revered the Bible compared to (what can be termed) the “original” Decalogue. This is understandable for several reasons. First, the original Decalogue is much more concise and more readily summarized than the cultic Decalogue. Second, the original Decalogue is provided in two places in the Bible, causing it to stand out a little more. But thirdly—and perhaps most importantly—the original Decalogue addresses categories that are of more universal moral concern than the cultic Decalogue addresses.

The last six or seven commandments (depending on how they are numbered) in particular would be important ethical principles to consider even for the non-religious. They address questions of truth and trust (bearing false testimony), life and death (murder), sexual ethics (adultery), and greed (covetousness)—all matters salient to anyone who takes ethical questions seriously.

The first three or four commandments (again, depending on how they are numbered) would be categorized as religious rather than moral in most modern contexts, and for that reason can sometimes be relegated to the same obscure place as the cultic decalogue in the modern mind.

However, whether or not its relevance continues today, in its context within the Bible, this juxtaposition of religious and morally charged commandments is intentional. Genesis famously presents humanity as having been made in the divine image. In its context, this means that human beings represent the divine in the world. In a sense, this presents humans as both collectively and individually the idols of God. The Decalogue therefore forbids the making of carved (manmade) images of a deity because living persons alone are supposed to be God’s image. Reverence for God in this way is made to connect directly to human society.

Why Do the Religious Commandments Come First?

The Ten Commandments are arranged so that the Sabbath command acts as a hinge between the first few commandments (which are the most overtly religious) and the final six or seven commandments, which address issues of inter-human, ethical relationships. Why does the Decalogue follow that structure?

Biblical law seems to envision the Sabbath command as the intersection that connects religious and ethical life. In the Decalogue of Exodus, the Sabbath’s purpose is to memorialize God’s rest after creation week. But in Deuteronomy’s Decalogue, which many scholars believe to be a later version, the text explains that the Israelites must rest in order to remember that they were once enslaved in Egypt, and that God delivered them from slavery. This is why the Israelites must provide a weekly day of rest for their own slaves. Thus, while from a modern perspective Sabbath-keeping can appear to be a purely religious matter, in the Decalogue as well as elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible, it is presented as the connecting point between the divine-human and inter-human axes of life—the “vertical” and “horizontal” planes of human experience. This reflects, in turn, the worldview of the Hebrew Bible, which envisions religion and ethics as ultimately inextricable.

Are the Ten Commandments the Pinnacle of Biblical Law?

There are several features of biblical law that make it stand out from other ancient law collections that have been discovered by archaeologists. For one thing, all biblical law has been passed down in the context of a wider narrative—namely, the story of the Bible. Traditionally, those who are interested in the ethical world of the Bible look not only at the commands themselves, but also the stories in which those commands appear. They also often try to reconstruct the possible historical settings in which the laws were written with the hope of gaining a better understanding of what social ills they were intending to correct.

Some other features unique to biblical law are epitomized in the Ten Commandments.

First, biblical law is often presented in the form of direct commands. Other ancient laws tended to be written in an “if-someone-does-this-then-give-this-punishment” format. Many laws in the Bible are worded like this as well. However, much of biblical law is presented apodictically—meaning, in an absolute “you-shall” or “you-shall-not” format, with no consequences delineated. The Decalogue is a prime example of this.

Another unique feature of biblical law is exemplified in the Decalogue’s final command against covetousness. Coveting is a matter of one’s inner life—it is impossible to regulate through laws. Yet, unlike other ancient legal traditions, the Bible sometimes includes commands about inner life.

Finally, as noted above, the Ten Commandments also represent the ethical vision of the Hebrew Bible as a whole, which intentionally merges ethics with religious devotion. Thus, there is a sense in which the Ten Commandments encapsulate biblical law in a special way.

Nevertheless, the Ten Commandments are not viewed in the rest of the Bible as more or less absolute than other biblical laws. The great Rabbi Akiva, for example, as well as Jesus famously pointed to the commandment to love God and love one’s neighbor as the Bible’s two greatest commandments.