Many see the fall of the Aztec Empire and the subsequent conquest of Mexico as a result of the wit and boldness of Hernán Cortés and his conquistadors’ endeavors. However, without the help of Tlaxcalan warriors, the Spanish never would have taken the great city of Tenochtitlan. The Tlaxcalans were the main allies of the Spaniards, and their role was crucial for numerous Spanish expeditions. Thanks to their help and loyalty, Tlaxcala became the small cornerstone of the Spanish Empire.

Tlaxcala, the Old Enemy

Tlaxcala and Tenochtitlan, protagonists of Mexico’s conquest, have histories with interesting parallels. They both were descendants of the Chichimeca, a people from the distant northwest. Chichimeca groups founded both settlements in the 14th century CE. Both Tlaxcalan and Mexica ancestors belonged to the Nahua ethnic group and spoke variants of the same language. Moreover, both were considered savages by the civilizations of the Mexican Basin and the Central Valley, and they had to fight to earn a piece of land.

Tlaxcalan families arrived in the Mexican Basin following the instructions of their god, Camaxtli. They first approached Lake Texcoco but instead of stopping there, continued to the mountains in the east. That journey was not easy; the local tribes, namely Olmeca-Xicalancas, Huejotzingas, and Tepanecas, attacked the Tlaxcalans continuously, perhaps prompting the birth of their warrior spirit. They defeated their local rivals and founded Tepectipac in 1380.

The expansion of Tlaxcalan power continued as they founded three other city-states: Octelulco, Tizatlán, and Quiahuixtlan. Together with Tepectipac, they created the Tlaxcalan Republic—Tlatoloyan Tlaxcalan—a confederation in which each lord had equal authority to decide on common issues while governing the internal affairs of their respective lands. Although this type of organization was not a democracy, the presence of representatives from each region debating as equals has been identified as a type of senatorial organization by modern historians, the Tlaxcala Senate.

The Tlaxcalans became the mightiest force in the modern Puebla-Tlaxcala mountain range. However, they had powerful and dangerous enemies to the West: Tenochtitlan, a city-state founded by another Chichimeca group, the Aztecs. The Aztecs built an alliance with the cities of Texcoco and Tlacopan while subjugating other cities and tribes, surrounding the Tlaxcalan territories.

The Aztecs could not defeat Tlaxcalans directly but forced them to participate in the Flower Wars. These consisted of ritual battles with the purpose of capturing warriors for human sacrifices. The Aztecs, imposing tributes on the neighbors of the Tlaxcalans, isolated them and blocked their commercial routes, even banning the trade of certain goods, such as salt. During the 15th century, the Tlaxcalans endured commercial and political isolation while continuously preparing for a new military confrontation.

Tlaxcala & the Conquistadors: Unlikely Allies

The enmity and the Flower Wars continued for decades. Meanwhile, in the early 16th century, people from the Mexican Basin began to hear rumors of the arrival of strangers, bearded men coming from across the sea. Neither the Aztec nor Tlaxcalans could have predicted how these foreigners would change their fates when Hernán Cortés arrived with a band of conquistadors from the Spanish Antilles.

Cortés and his men, aware of the wealth of Tenochtitlan, reached the rough mountain range that lies between the Gulf Coast and the Mexican Basin, where the Tlaxcalans were fighting for survival against the Aztecs. The Tlaxcalans were hostile to foreigners near their territory, so they sent troops from their main allies, the Otomí, to chase away the intruders. The main battle between the Otomi and the Spanish occurred on September 2, 1519. The conquistadors obtained the victory and continued on their path through the mountains.

The Tlaxcalans reacted to this defeat by sending their own troops. The commander of the Tlaxcalan army was Xicotencatl Axayacatzin, called the Younger, son of Xicotencatl the Elder, lord of Tiztlán. Xicotencatl tried in many ways to crush the Spaniards and their allies in a series of battles, but, despite the severe damage inflicted on the conquistadors’ forces, he could not break their defenses.

The Spaniards revealed themselves as formidable opponents. After a final series of skirmishes, both parties acknowledged the strength of the other. The different Tlaxcalan lords discussed the situation and, against the will of the younger Xicotencatl, who perceived a threat to his people, decided to invite Cortés to their lands to form an alliance.

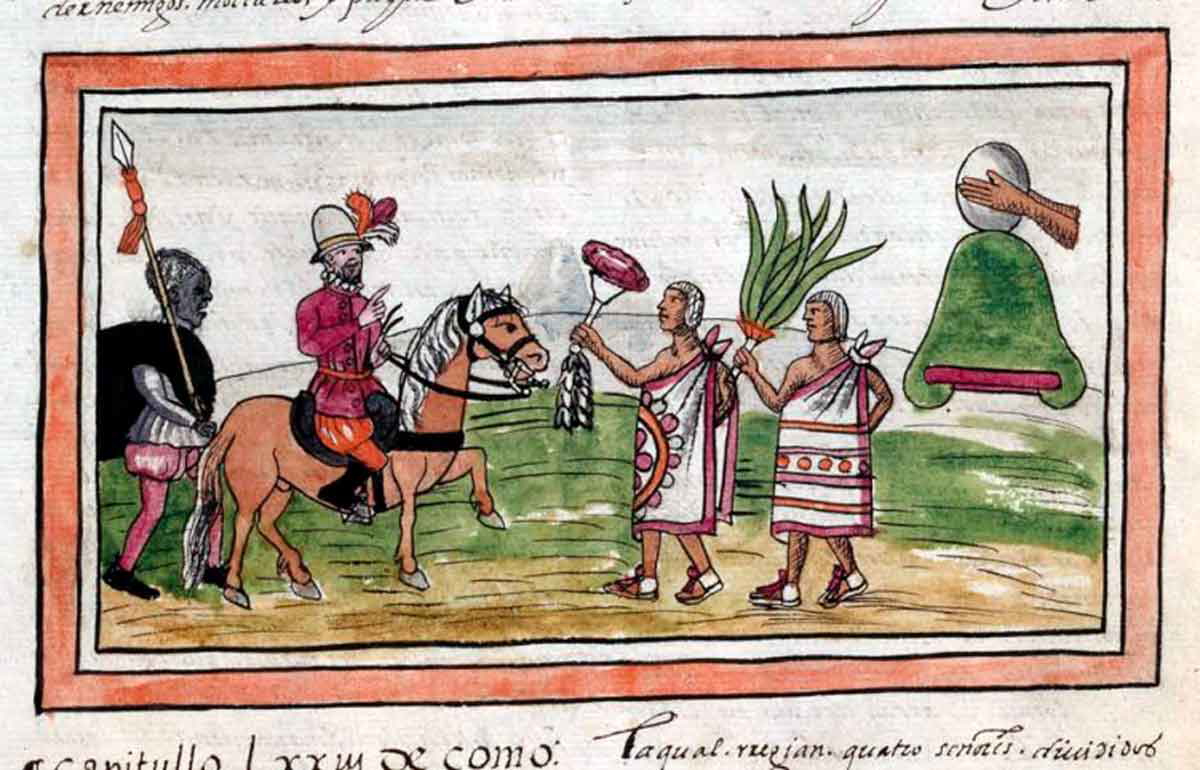

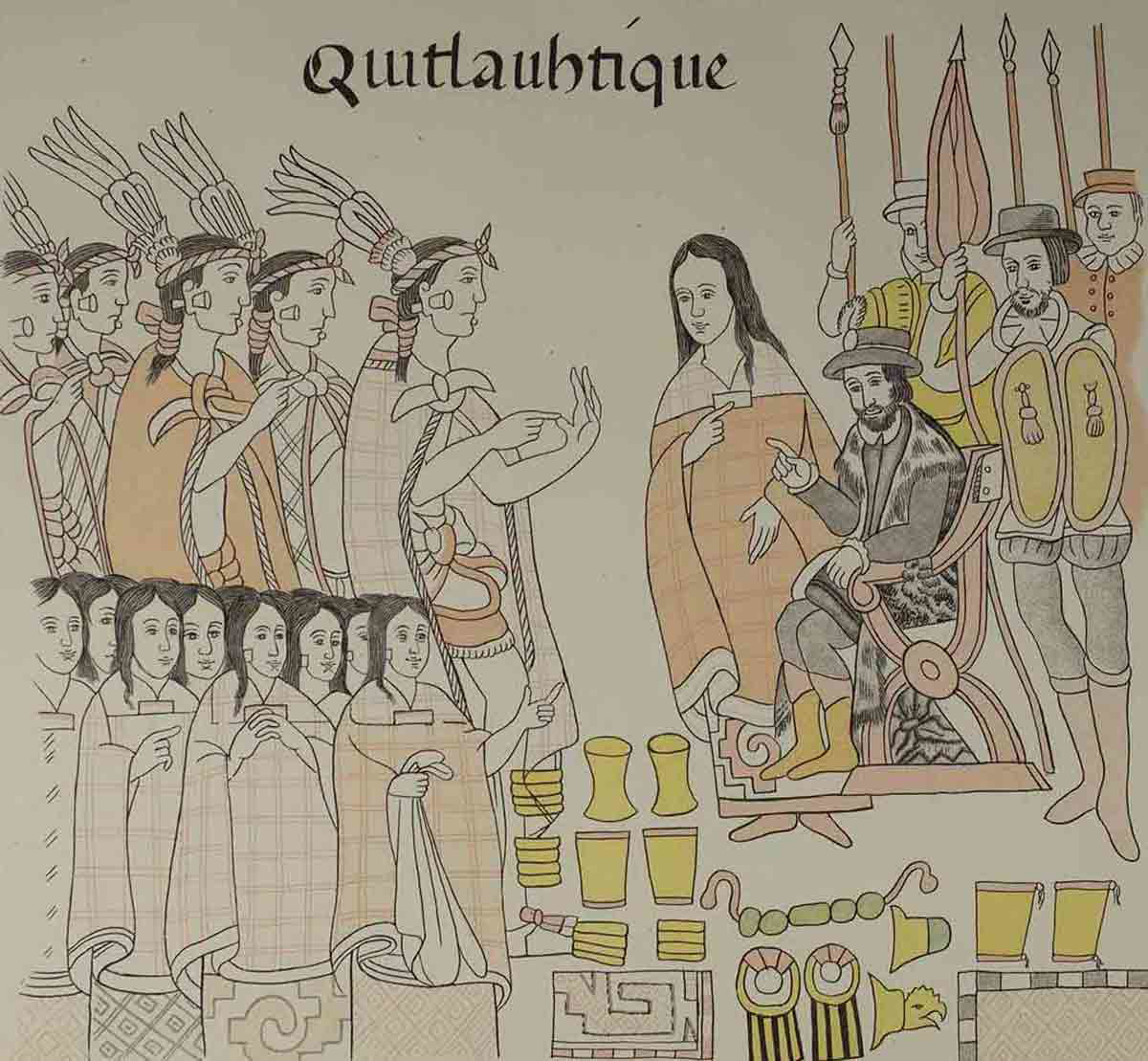

Cortés traveled to Quihuiztlan, where the lord Citlalpopoca gave many gifts to the Spaniards, including offering the men a number of noble ladies’ hands in marriage. This tactic would be essential to establishing ties beyond politics or war. Through Malintzin as an interpreter, Cortés offered friendship in the name of Emperor Charles V and vengeance against the Aztec Empire. The subsequent baptism of the Tlaxcalan lords was a symbol of the beginning of a new pact of friendship.

Still, Cortés had a tense relationship with Xicotencatl the younger. The Tlaxcalan general agreed to join forces with the Spaniards, but he never trusted Cortés or any of the conquistadors. Despite his courage and expertise in war, key to Cortes’ plans, the young general never saw the Spaniards as true allies and suspected that they were using his people without intending to share the wealth or the lands conquered.

In November 1519, the army arrived in Tenochtitlan. Moctezuma gave a splendid welcome to the foreigners, including the enemy Tlaxcalan warriors. Cortés decided to stay in the city to search for the treasure of the Aztec, though there was no solid evidence of that fabled wealth.

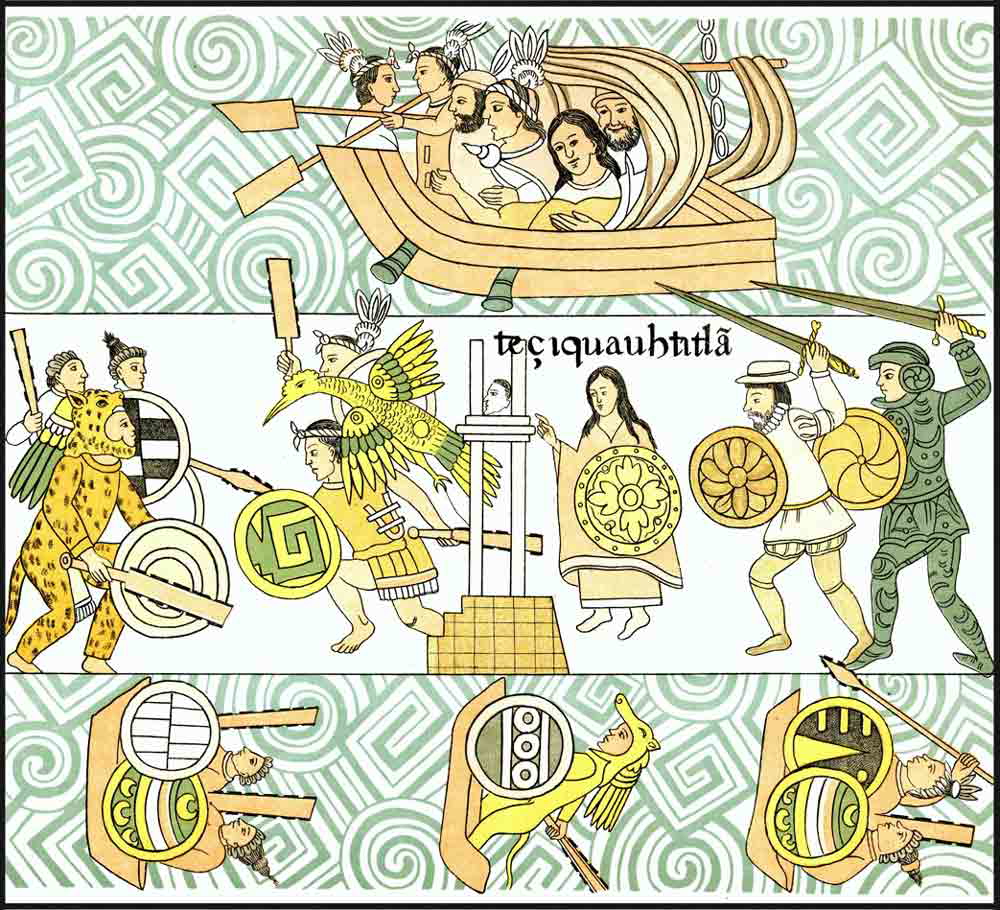

The presence of the strangers was displeasing for the inhabitants of Tenochtitlan, and after a massacre at the great temple on May 20th, riots started. Moctezuma was unable to contain the rebellion, and legend says that the mob stoned him to death. The Spaniards and Tlaxcalans understood that they could not stay in the city any longer and decided to escape. On the night of June 30th, as Cortés’ troops tried to sneak out without notice, the Aztec army surprised them. Many of the Spaniards and Tlaxcalan warriors were killed, and others drowned in Lake Texcoco. The defeat, called La Noche Triste (Sad Night), was humiliating—according to legend, Cortés wept with rage. But more importantly, it increased Xicotencatl’s resentment towards the Spaniards.

The Battle of Tenochtitlan

Cortés and what was left of his army tried to return to Tlaxcala. They were still close to Tenochtitlan, in a place called Otumba, when they were attacked by a large Aztec army led by Matlazincatzin. The Aztecs surrounded Cortés’ army but could not break their defensive line. Tlaxcalan warriors told Cortés that if they killed Matlazincatzin and captured the royal standard, the battle would be over. Cortés followed this advice and charged with the few riders remaining against the Aztec general. When the Spaniards took the royal standard, the Aztec troops, confused and scared, retired, even though they still outnumbered Cortés’ forces.

The unlikely victory allowed Cortés to return to Tlaxcala, where he began to plan an assault on Tenochtitlan. Most of the Tlaxcalan leaders agreed to participate, but Xicotencatl did not. Going against his father, he decided to break his alliance with Cortés. Though not many of his own men accompanied him, from that moment on, Xicotencatl was a constant threat to Cortés and the Spaniards. His rebellion lasted for less than a year. In May 1521, the Spaniards captured him. Tlaxcalan leaders and Spaniards together charged him with conspiracy and treason, and he was executed. Xicotencatl’s death cleared the way for a combined army of Spaniards and Tlaxcalans, with troops from other vassal peoples, such as the Otomi and Texcocan.

By this time, the decisive battle was set. With the considerable number of Indigenous warriors under his command and the preparations completed, Cortés returned to Lake Texcoco to seize Tenochtitlan on May 21, 1521. The Aztec defenders were first devastated by a smallpox outbreak transmitted by the Spaniards, then began to lack drinking water and food due to the blockage of their supply routes. Almost three months later, on August 13, 1521, Cuauhtémoc, the last Aztec ruler, was captured, and the city, in ruins, surrendered.

At the Service of the Emperor

For the Tlaxcalan, the defeat of Tenochtitlan meant the destruction of their greatest enemy, and they viewed themselves as conquerors. Cortés immediately organized the reconstruction of Tenochtitlan, which would be called México or Mexico City. But, much to his despair, the legendary treasure of the Aztecs was smaller than he thought and would not satisfy the emperor nor his men as a worthy spoil of war.

This situation motivated Cortés and other conquistadors to start a new series of expeditions to the south and north of the former Aztec territories. Once more, the Tlaxcalans agreed to join them. Soon after the fall of Tenochtitlan, in 1523, the conquest of the Mayan lands on the Yucatan Peninsula and present-day Central America began. Now under the command of Cortes’ former lieutenant, Pedro de Alvarado, the Tlaxcalans helped to establish Spanish dominion over Chiapas and Guatemala.

The Spaniards relied on the Tlaxcalans both for pacification and conquest. The empire’s new possessions soon would constitute a territory larger than Spain itself, and the Spaniards could not maintain control without help, so Tlaxcalan families would move and settle in diverse villages to work as laborers, masons, artisans, and, of course, security forces. Meanwhile, there were immense expanses of land to the north of the Mexican Basin with the promise of gold and silver mines but also the threat of fierce and untamed tribes; expeditions into these territories needed the skill of Tlaxcalan warriors to defeat the hostile parties.

To keep the Tlaxcalans on their side, the Spaniards granted many privileges to their allies. After the Christianization of the majority of Tlaxcalans circa 1524, several dispensations were approved by the Spanish Crown to protect the Tlaxcalans. While many of the conquered peoples were forced to work on encomiendas—large estates where natives worked and paid tribute to a Spanish lord—Tlaxcalans preserved a high degree of autonomy and were not subject to many of the taxes imposed on the other natives.

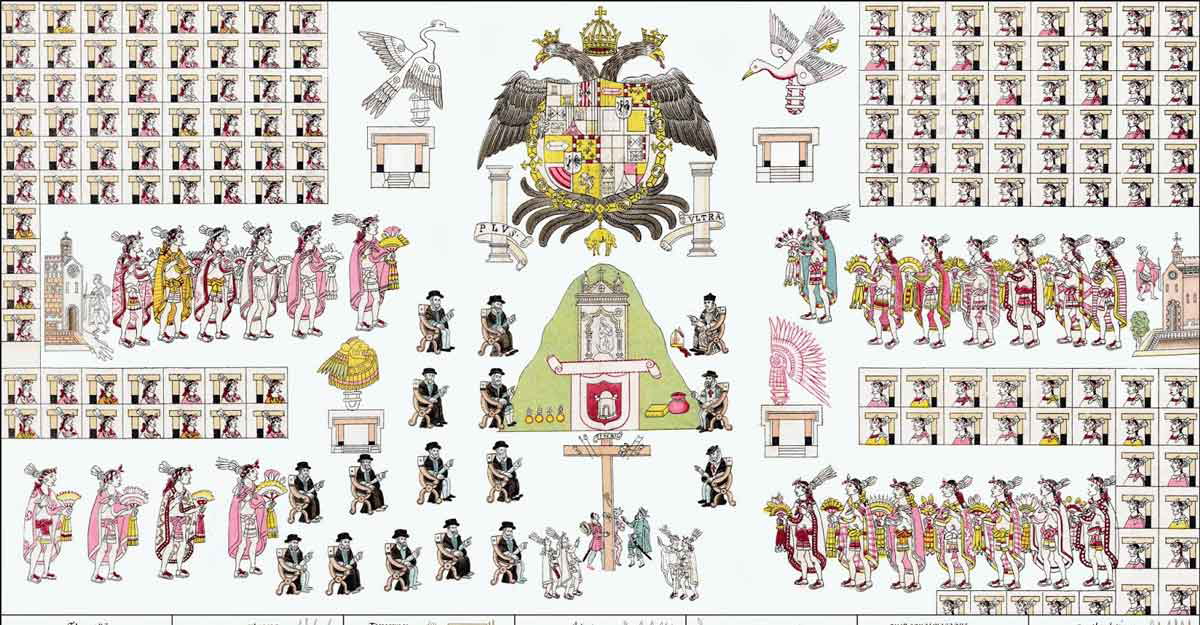

A proper city of Tlaxcala was founded in accordance with Spanish law in 1525, and in 1527, a group of Tlaxcalan representatives traveled to Europe to meet Charles V. The Crown was so pleased with the services of the natives that, in 1535, when the first viceroy arrived in Mexico, Tlaxcala received a coat of arms and the title “Illustrious, Very Noble and Very Loyal.” The Tlaxcalans maintained their loyalty to the Spanish Empire in the following decades. They accompanied new expeditions to the north and east of Mexico. They reached both the Pacific Coast and the Sierra Madre Heights, contributing to the exploration and colonization of territories such as Sinaloa, Zacatecas, and Durango.

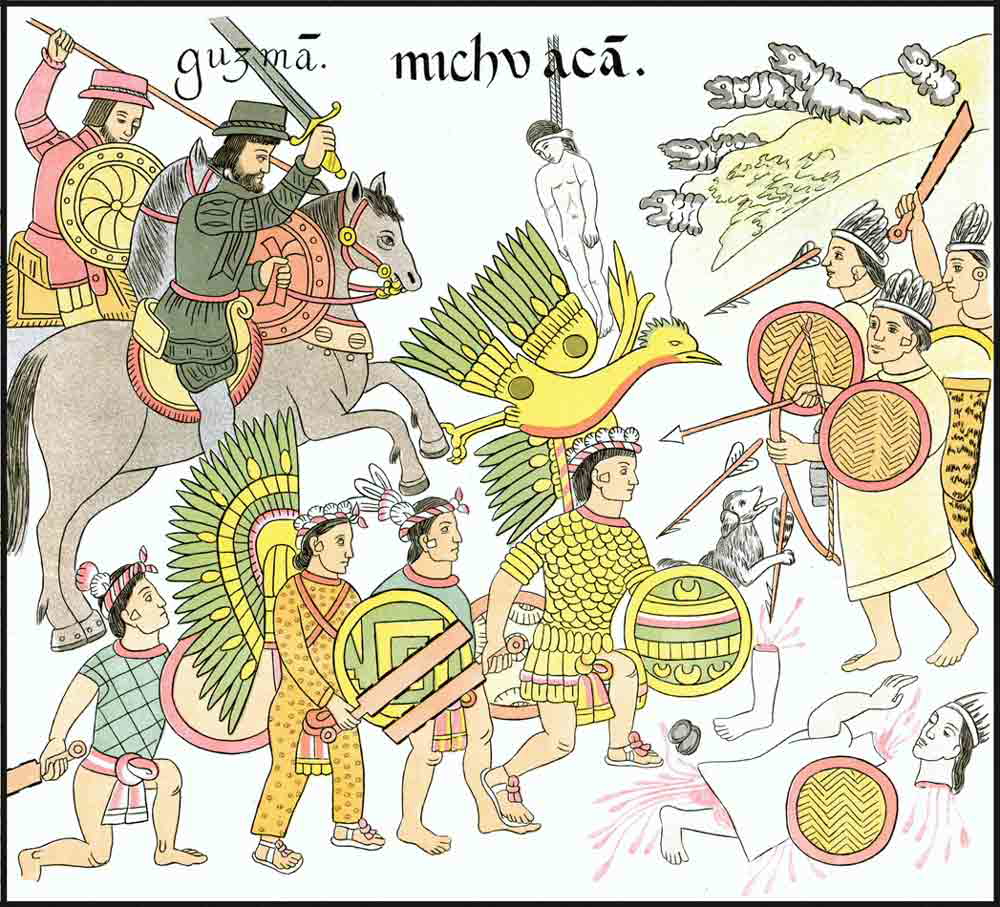

To emphasize their position as loyal servants, the Tlaxcalan city council ordered the creation of the Tlaxcala Canvas, a collection of paintings depicting their encounters with Spaniards, their fight against Tenochtitlan, and the subsequent campaigns to the north and south. The canvas was finished in approximately 1552. Sadly, the three original pieces are lost, but some copies survived and now represent one of the most important documents concerning the conquest and the beginning of the colonial era in Mexico.

Tlaxcala and the New Mexican Nation

Despite their degree of autonomy and the special privileges granted by the Spanish Crown, Tlaxcala was never a rich province within the viceroyalty of New Spain. The population decreased, and the territory did not have the dynamic economy of Mexico City, Puebla, Guadalajara, or Veracruz. Yet the pride of the Tlaxcalans remained. In 1786, when King Charles III tried to incorporate Tlaxcala into the greater Puebla territory, Tlaxcalan representatives protested, and the Tlaxcala recovered their territories and autonomy in 1793. When Spain organized a Congress with representatives from all its territories in 1809, Tlaxcala did not receive an invitation. Once more, the Tlaxcalans demanded to be present in consideration of all the services and titles conceded to their ancestors. The Spanish government agreed, and Tlaxcala sent its representatives to participate in writing the ill-fated Cadiz Constitution.

Tlaxcala did not play a major role in any of the 19th-century social movements. Remarkably, its territories were not altered during the tempestuous times of the early independent Mexican governments. Both the Constitution of 1824 and that of 1857 recognized Tlaxcala as a federal sovereign state, preserving the limits of the ancestral city-states that were never conquered.

Tlaxcala did not maintain the prestige it had enjoyed in the colonial era. As Mexican nationalist sentiment grew, the belief in a great Mexican nation that had been unlawfully subjugated by foreign powers became the most accepted version of history. In 1840, President Benito Juárez called the Tlaxcalans “vile traitors” who preferred to help the Spaniards defeat Tenochtitlan than preserve the independence of the nation. After that, resentment toward the Tlaxcalans increased, and for decades, they were counted among the enemies in Mexican history. Juárez’s speech maintained a strong hold on the collective consciousness, and even a century later, in 1964, the famous writer Elena Garro wrote a tale titled La culpa es de los Tlaxcaltecas (“It’s the Tlaxcalans’ fault”).

Traitors?

The role of the Tlaxcalans in the defeat of Tenochtitlan and the creation of the Spanish Empire remains controversial to this day, as with many other aspects of Mexico’s colonial past. Mexico as a state did not exist at the time of the conquest and Tlaxcala people did not owe any loyalty to Tenochtitlan. However, the question of whether the Tlaxcalans were traitors or not has produced a great number of political, cultural, and scholarly positions.

Tlaxcala is an interesting piece of the puzzle that constitutes the development of Mexican national identity. Octavio Paz wrote about the inability of Mexicans to accept themselves and reconcile with their troubled past, with both the Indigenous and Spanish legacies forging a new nationality. Tlaxcala is a mirror for the contradictions in Mexico’s understanding of its past and present.

Within the most common perspective, presenting the conquest of Mexico as a tragedy, with the heroic Aztecs fighting until the very end and portraying the conquerors as vicious villains who exterminated any trace of local culture—both quite inaccurate—the Tlaxcalans take on the role of traitors that helped to enslave their fellow Indigenous brothers and precipitated the ruin of the lands’ ancient glory.

Nevertheless, the people of Tlaxcala remain proud of their origin and history, despite the label of “traitors” lingering in the collective memory of the nation. They see themselves as part of the victorious side of a great confrontation that changed history, but they do not deny their origins. Whereas Tlaxcala keeps the coats of arms granted by King Phillip II, they still call themselves “Tlaxcaltecas,” and the official name of the capital city is “Tlaxcala of Xicotencatl,” honoring the general who fought against the Spaniards, even against the advice of the other lords.

The Tlaxcalans stand out as an example of a nation that adapts to changing times without losing its connection with its origins. They endured against more powerful enemies, and they forged alliances that allowed them to prevail. In addition, they used their strength and courage to maintain a favorable position in a new political order and expand their dominion and culture. These considerations offer a new perspective on one of the most relevant and misunderstood actors in the history of Mexico.