At the end of the 15th century, Spain entered an era of brutal religious persecution, defined by the Spanish Inquisition. This organization is remembered as a symbol of terror, abducting, torturing, and executing all those deemed heretics. Against such a formidable institution, Muslims, Jewish people, and Catholics not born into the religion were targeted and suffered horrendous cruelty in the name of God and Catholic orthodoxy.

Leading the Inquisition was Tomás de Torquemada, a Dominican friar who would go down in history as a man of ruthless zealotry and fervent devotion whose name struck fear into the hearts of all those he opposed. The truth of Torquemada, however, is a bit more complex.

The Early Life of Tomás de Torquemada

Tomás de Torquemada was born on October 14, 1420, although it is unclear exactly where. Accounts suggest Valladolid, the Kingdom of Castile, or the village of Torquemada. There has also been debate over Torquemada’s lineage as to whether or not his uncle, Juan de Torquemada, was of converso descent, or in other words, descended from somebody who had converted to Catholicism from another religion. A study in 2020 showed no evidence of this. Conversos were a particular target of the Spanish Inquisition.

A prominent member of Tomás’ family, Juan was a well-known theologian and a cardinal, and like his uncle, Tomás found himself attracted to a religious life. As a young boy, Tomás entered the San Pablo Dominican monastery, where he led a life of dedication and became a profound supporter of orthodoxy. He was pious, austere, and earned a solid reputation in religious circles.

Tomás took his vows as a Dominican friar at the Convent of St. Paul in Valladolid, studied further, earning a doctorate in philosophy and divinity, and earned a reputation for extreme austerity. He never ate meat, and he never allowed linen (a luxurious textile at the time) to be used in his bedsheets. In fact, he shunned all forms of luxury and suffered a lifestyle of extreme asceticism. His reputation garnered considerable respect, and he was elevated to the post of Prior of the monastery of Santa Cruz in Segovia. In this capacity, he met with the young Princess Isabella I. They developed a good relationship, and Torquemada acted as Isabella’s confessor.

Gaining considerable trust from the princess, Torquemada became Isabella’s most trusted advisor and convinced her to marry King Ferdinand of Aragon in 1469, which resulted in a de facto unification of Spain. Gaining the trust of the king, Torquemada acted as his confessor as well.

The Path to the Inquisition

In the latter half of the 15th century, Spain became a nation reborn. The Reconquista had consolidated Spain and driven out foreign occupiers, but it resulted in Spain having large populations that were not born into Catholicism. Aside from the Catholic inhabitants of Spain, there were large populations of conversos and moriscos, Jewish people and Muslims respectively, who had converted to Catholicism. Conversos also included marranos, who were specifically Jewish people who had converted to Christianity and who lived in Iberia.

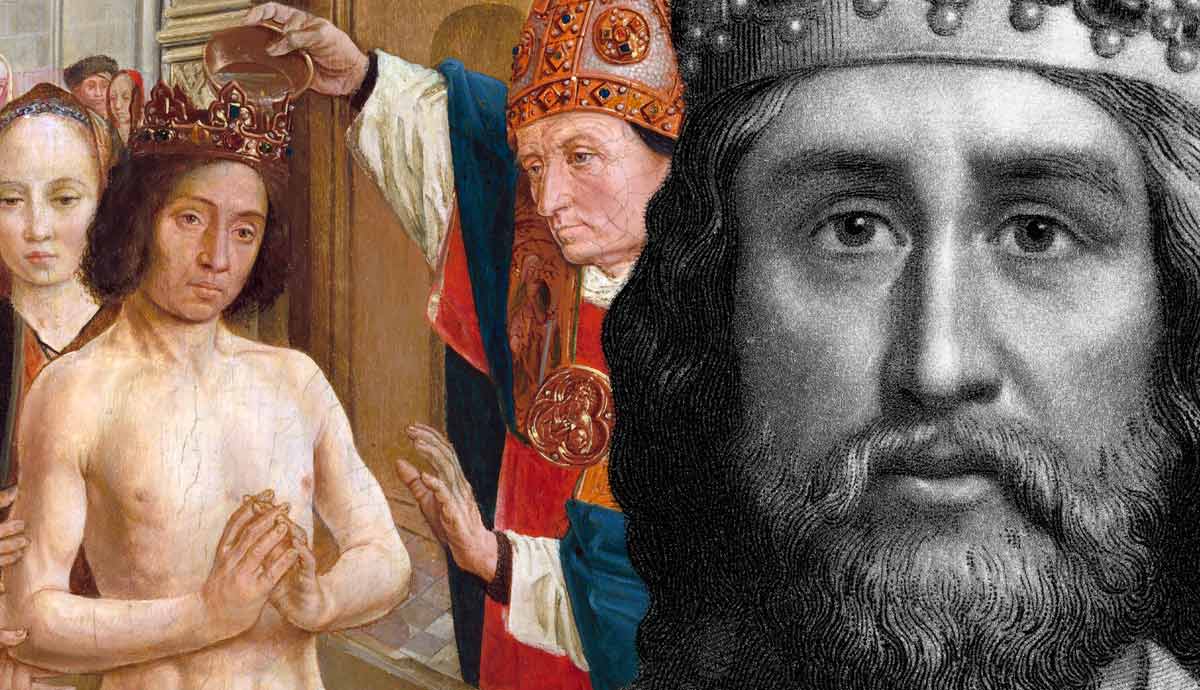

As co-monarchs, Ferdinand II and Isabella I ruled over Spain and desired a unified country, not just politically, but religiously. Through them, religious intolerance and persecution followed. As such, the Spanish Inquisition was established in 1478 with the authority of a papal bull, Exigit Sinceræ Devotionis, granted by Pope Sixtus IV. The Latin phrase translates as “demands sincere devotion,” and it justified the acts that were taken by virtue of extreme devotion and faith of those involved.

Conversos and moriscos were prime targets as the Inquisition sought out false converts and those it suspected of being insincere in their Catholic beliefs, practicing other religions in secret. In later years, as the Protestant Reformation took shape, Protestants also became the victims of harsh interrogations and torture. The Inquisition began, although at this time, Torquemada had not been elected Grand Inquisitor yet.

Grand Inquisitor Torquemada

Tomás de Torquemada was one of the seven inquisitors appointed by the pope in 1481, and in 1483, he ascended to the position of Grand Inquisitor at the head of the Spanish Inquisition. In this powerful position, Torquemada set about transforming the Inquisition from a single tribunal in Seville into a vast network that spanned the kingdom.

The struggle for power, however, was not straightforward. In the early years, the Inquisition was not a single unified body, but rather, a collection of independent inquisitions. There was also debate over ultimate control. Pope Sixtus IV accused the Inquisition of being motivated by wealth rather than religious fervor. King Ferdinand was outraged and denounced the accusation. However, the debate was resolved when Pope Innocent VII withdrew all papal inquisitors from Aragon and Catalonia. Torquemada took full control, being appointed as Grand Inquisitor of all of Spain in 1487.

He instituted articles of faith on how investigations were to be conducted and instructions on the use of torture to extract confessions. While the Inquisition has come to be seen as particularly brutal, it is salient to note that the use of torture with regard to the treatment of accused heretics was nothing new and had been instituted before. There is, however, debate over how often torture was actually employed by the Inquisition.

Nevertheless, Torquemada now stood at the head of a powerful and fanatical organization, willing to commit to violence to achieve its ends. In this, Torquemada was the architect of what was to follow.

Torquemada, the Man

Torquemada was driven by intense zeal and his dedication to the Catholic faith. The methods he employed gained him particular notoriety, as well as respect. Very little is actually known of him, and despite the modern depiction of him as a brutal sadist, there were many contemporaries who spoke well of him. The chronicler Sebastien de Olmedo referred to Torquemada as “[t]he hammer of heretics, the light of Spain, the saviour of his country, the honour of his order.”

It can, however, be argued that Torquemada was the one rightfully responsible for the brutality that the Inquisition wrought, and his name can be justifiably cast in shadow. His actions led to the torture and deaths of thousands and contributed significantly to an atmosphere of fear and oppression in Spain as well as its territories during the era of Spanish colonialism.

Another perspective on Torquemada was that he was an ascetic who shunned lavish lifestyles, in stark contrast to many other religious figures at the time who made no attempt to hide their wealth.

The Inquisition — A Defining Feature of Torquemada

Torquemada is known, above all things, as the architect and leader of the Spanish Inquisition, which is remembered for its brutal procedures against perceived heretics.

For those who became victims, accusations could come from anywhere. Denunciations were often anonymous. The Spanish Inquisition acted in defiance of papal constraints on the use of torture, and if suspects failed to confess, they could be subjected to extreme physical duress. The prevalence of torture, however, is highly debated. Scholars have pointed out that the Spanish Inquisition did not use torture to the same extent as secular courts, and some cite a lack of evidence for torture and attribute much of the negative publicity to Protestant propaganda.

Nevertheless, executions were public and took place as a ceremonial event called an Auto-da-Fé (Act of Faith). Over their heads, the condemned wore sackcloth with a single eyehole, and were burned at the stake in front of large crowds, often including royalty, while the Grand Inquisitor looked on.

Of major note was the expulsion of Jewish people from Spain in 1492, heightening the air of intolerance in the kingdom. Torquemada played a pivotal part, convincing the monarchs that unbaptized Jewish people were a threat to Christians. The Alhambra Decree was issued, evicting Jewish people from Spain under threat of death. All those who aided them were also threatened with dire consequences, including the seizure of all property.

While the existence of the Inquisition’s cruelty cannot be denied, the extent of it and its existence in a broader context are topics of great debate. Similarly, Torquemada’s legacy is one of confusing portrayals and perspectives that omit proper interrogation.

A Confusing Legacy

Much of what is known about Torquemada comes from firsthand accounts and historical records of the time rather than any personal writings made by the Grand Inquisitor. There is a great divide between those who supported him and those who condemned him. In modern depictions, he is often painted with the brush of sadistic cruelty and exists as a two-dimensional character rather than a complex human being.

As such, the truth about who Torquemada was is difficult to ascertain and is subject to supposition and common tropes. In The Pit and the Pendulum (1991—one of many adaptations with this title), Torquemada is depicted as the sinister villain at war with heretics as much as with himself and his natural urges towards a particular woman. In Torquemada (1989), the titular character is equally tyrannical and macabre. Other depictions follow in the same vein, while in History of the World Part 1 (1981), Mel Brooks gives the character of Torquemada a more amusing (and musical) quality.

In the real world, some of his legacy was quite clear. He died in his sleep in 1498, but left a powerful inquisition in his wake. His work left Spain far more unified than it was before, albeit also more intolerant. The Inquisition formally ended in the first half of the 19th century.

Whether justifiable or not, the name of Torquemada, in the modern era, is associated with ruthless fanaticism and brutality. And in a world that is significantly more liberal than the one in which he lived, it seems unlikely that his name will be remembered for anything other than the perceived horror of the Spanish Inquisition.