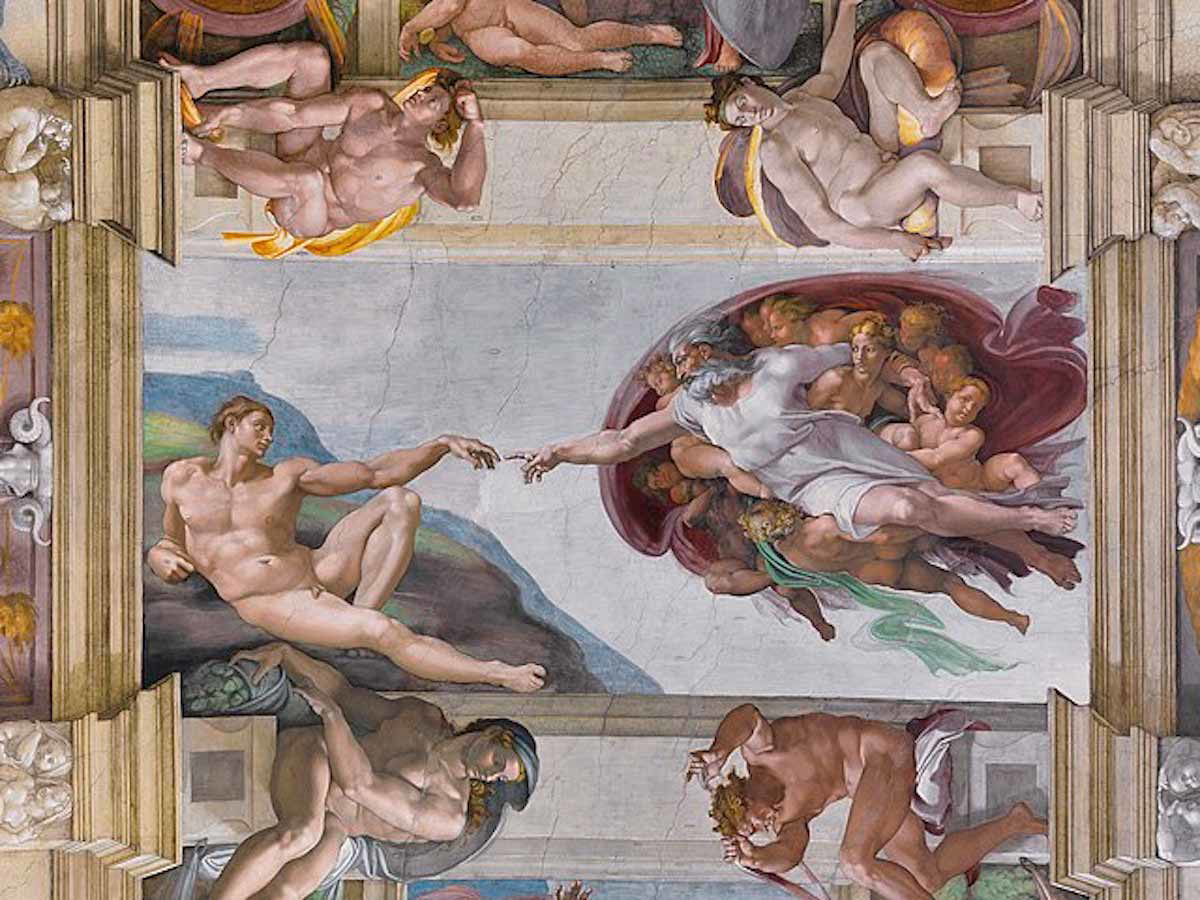

The Sistine Chapel, located in Vatican City in Rome, is famous for the frescoes on its walls and ceiling. Although numerous renowned artists of the late 15th century contributed to the chapel’s walls, perhaps the most celebrated frescoes are those covering the ceiling and the altar wall. In 1508 Pope Julius II commissioned Michelangelo Buonarotti to paint the ceiling and lunettes on the upper part of the wall.

Ultramarine: A Timeless Status Symbol

Michelangelo completed the work in 1512 after four painstaking years of standing and craning his neck on a purpose-built scaffold (not lying on his back, as legend has it). Like the chapel’s wall frescoes, his work shone with the blue of ultramarine. This use of the costliest pigment, extracted from the rare semi-precious lapis lazuli, defined the awe-inspiring beauty of the Sistine Chapel as we see it today.

Throughout the history of Western art, we have associated blue, particularly ultramarine, with the robes of the Virgin Mary, the heavens, and sacred imagery in general. Only the ancient Egyptians came anywhere near displaying the reverence for blue in their artworks that the Western canon has shown. Although they used Egyptian Blue, known as copper calcium silicate, it was always a substitute for the much more expensive ultramarine made from lapis lazuli. Certain objects of high status, such as the death mask of Tutankhamun, justified the finest resources. Made in gold with inlaid lapis lazuli, the mask demonstrates what would become a timeless association of these precious materials with wealth, power, and, of course, the sacred nature of gods.

Paving the Way for Michelangelo

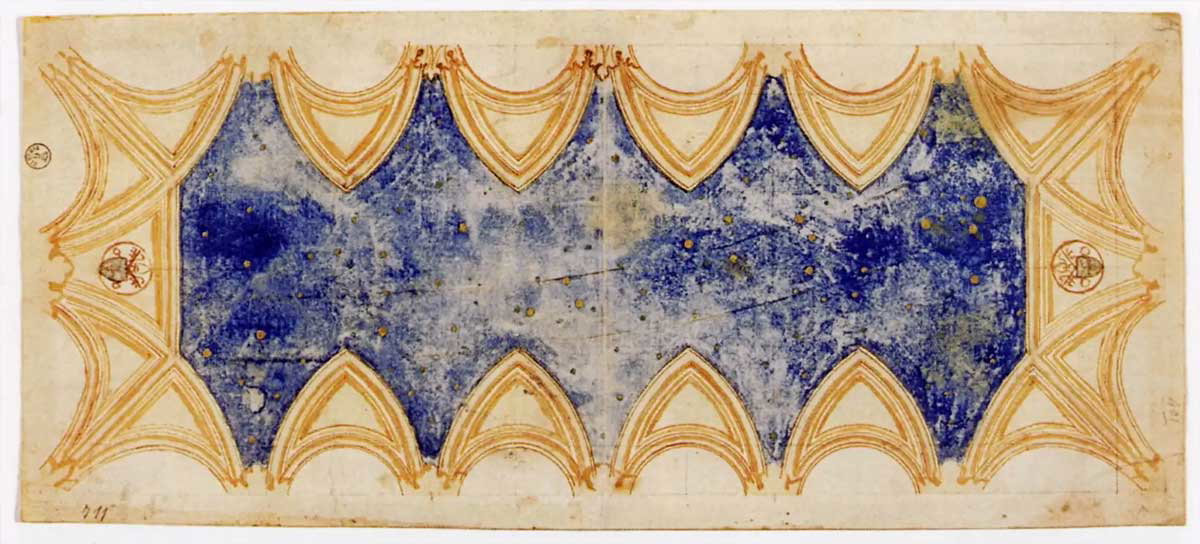

Fast forward to the 14th century and ultramarine is taking the Early Renaissance art world and its wealthy patrons by storm. Cimabue and his pupil, Giotto, were among the first to champion ultramarine in religious art. Giotto’s Scrovegni Chapel ceiling illustrates, in spectacular fashion, what a rich patron, willing to finance the extensive use of ultramarine, can achieve with the right artist. The profound blue of the ceiling, strewn with golden stars, paved the way for future generations of artists, among them the painters commissioned to decorate the newly renovated Sistine Chapel in the late 15th century.

The Cast Assembles: The Sistine Chapel Is Born

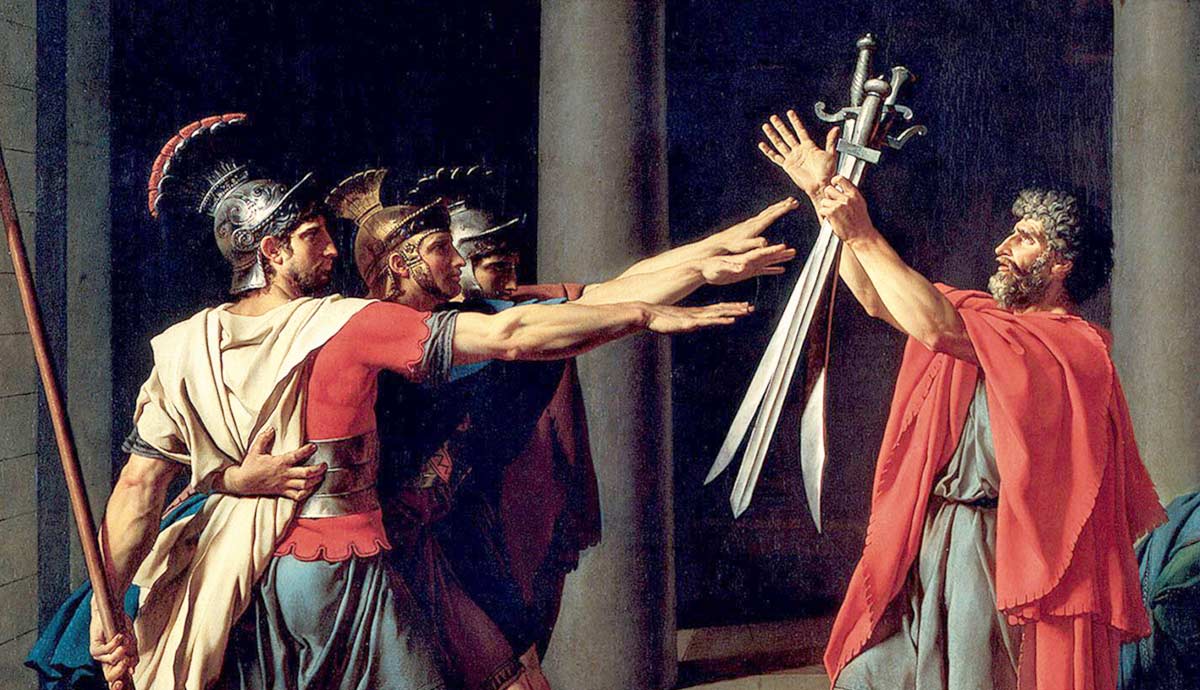

In 1481, Pope Sixtus IV, whom the Sistine Chapel was named for, commissioned the restoration of what had been the Capella Magna. A company of some of the most illustrious contemporary artists was employed to paint the chapel’s north wall with frescoes representing the story of the life of Christ and the south wall with the life of Moses. Sandro Botticelli, Pietro Perugino, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Pinturicchio, and Cosimo Rosselli were some of the artists who contributed to one of the finest fresco cycles in art history.

At this point, however, Michelangelo’s ceiling and altar wall were years in the future. His vibrant ultramarine skies would not be the first to adorn the Sistine Chapel. The original ceiling painting was executed at the same time as the walls, from 1481 to 1483. Pier Matteo d’Amelia created a star-filled sky using ultramarine and gold in a design reminiscent of Giotto’s Scrovegni ceiling. Piermatteo’s extensive use of ultramarine paid tribute to the elevated nature of the chapel, lying at the heart of the Roman Catholic church in the Vatican. Few commissions ranked higher than this. It was important to Pope Sixtus IV, and the artists selected, that the materials used in the chapel’s decoration were of the highest quality and reflected the importance of the location.

In 1504, the vault of the chapel began to develop structural cracks, rendering the chapel unsafe to use. Pope Julius II had the ceiling’s painted surface removed and it was at this point that Michelangelo was appointed to design and execute the replacement cycle of frescoes which remains to this day. Ultramarine, so dominant in Piermatteo’s ceiling, would feature less in the later ceiling of Michelangelo. However, the murals covering the chapel’s walls displayed the ultimate status symbol pigment in abundance.

If Walls Could Talk…

As we have seen, twenty years before Michelangelo received the commission to repaint the ceiling and lunettes of the Sistine Chapel, some of Italy’s principal artists were employed to decorate its north and south walls. Among them was Domenico Ghirlandaio, the man accredited as Michelangelo’s teacher. Ghirlandaio’s use of ultramarine in his Calling of the Apostles was wide-ranging. In keeping with his most reverent status as the Son of God, Christ is adorned in robes of ultramarine. Ghirlandaio’s depiction of the heavenly skies in the background reflects this theme. We see Christ’s figure repeated in the middle ground in another aspect of the story, his azure robe again highlighting his importance.

To the left of the fresco, an unidentified woman stands with her back to us. She, too, wears the ultramarine otherwise reserved for Christ in this work. As though to balance the artist’s use of the costly pigment, a pantheon of powerful Florentine families is depicted on the left of the image. Members of the Tornabuoni family, bankers to the Medici, and sponsors of Ghirlandaio remind us that, however venerable the location of the frescoes, money talks. Regardless of how the artwork was financed, the divine blue, so expansively used, elevates the beauty of the image, alongside the surrounding paintings, to a stellar level.

Heavenly Blue

Perhaps the boldest use of ultramarine in the Sistine Chapel can be seen in Rosselli’s depiction of The Sermon on the Mount. This feast for the eyes is awash with robes of blue in every shade. The richest blues are reserved for the robes of Christ, who appears in three areas of the work, illustrating him preaching the sermon, being followed by his disciples, and then healing the leper. Rosselli’s use of ultramarine, sometimes highlighted with gold, adds a vibrant beauty to the fresco. The color’s association with the heavens and divinity is clear.

The complete cycle of frescoes, albeit by various artists, is united by the ubiquitous application of ultramarine. Although the stories told by the artists concern some of the most momentous aspects of the lives of Christ and Moses, the inclusion of so many rich patrons in the scenes speaks to the cost of the work and the materials employed. Ultramarine was the most expensive pigment available to artists. Used often in tandem with gold, this rare blue had become associated with great wealth and divine beauty. However, if the artists painting the walls in the late 15th century were liberal in their use of ultramarine, Michelangelo’s employment of it, almost fifty years later, was prodigious for his Last Judgment.

Michelangelo’s “Last Judgment”

Depicting the second coming of Christ and the last day of judgment by God, Michelangelo’s largest fresco, painted over more than four years, also contains his most liberal use of ultramarine. Immediately upon hearing of his commission for the altar wall, Michelangelo began to buy stocks of the pigment. The vast fresco was to test the artist’s compositional skills, he was primarily a sculptor rather than a painter, and his rendition of the heavens in this most holy of chapels demanded the utmost generosity with materials. Michelangelo’s design was created to replace an earlier work by Perugino depicting the Assumption of the Virgin. Following damage by fire and general deterioration, Perugino’s work was chipped from the wall, and preparations for The Last Judgment commenced.

A Cast of Hundreds in a Sky of Blue

The roll-call of saints, sinners, the damned, and the saved swirls around the central figure of Christ in the painting. Ultramarine, whilst providing the background for this heavenly host, is more richly deployed in the robes of the Virgin as she clings close to Christ. The all-encompassing image of the muscular saints juxtaposed with the delicate figure of Mary does not detract from the vibrant blue skies but seems to forge an even stronger link between Christ and his earthly mother.

Suspended in the blue heavens, they are surrounded by over three hundred figures creating a complex display. Michelangelo’s composition was just one aspect of the piece that was criticized upon its completion. In addition, the nakedness of the figures portrayed caused an uproar, and decades later, after the death of Michelangelo, Daniele da Volterra, an admirer of the original artist, was ordered to paint over the genitalia of the figures in the fresco.

Sistine Chapel Ultramarine and Cardinal Red

From an artistic point of view, the use of ultramarine in the magnificent frescoes of the Sistine Chapel is perhaps best appreciated when seen alongside the scarlet robes of Cardinals during a papal conclave. Ultramarine illuminates the walls and ceiling of the chapel, emphasizing the holy red during the religious ceremonies for which it was built. Only when the chapel is cleared of awestruck tourists and returns to its intended use can this unbounded blue be appreciated in all its glory. For all its popularity with the great and good of society in the Renaissance, ultramarine remains the color of the heavens.