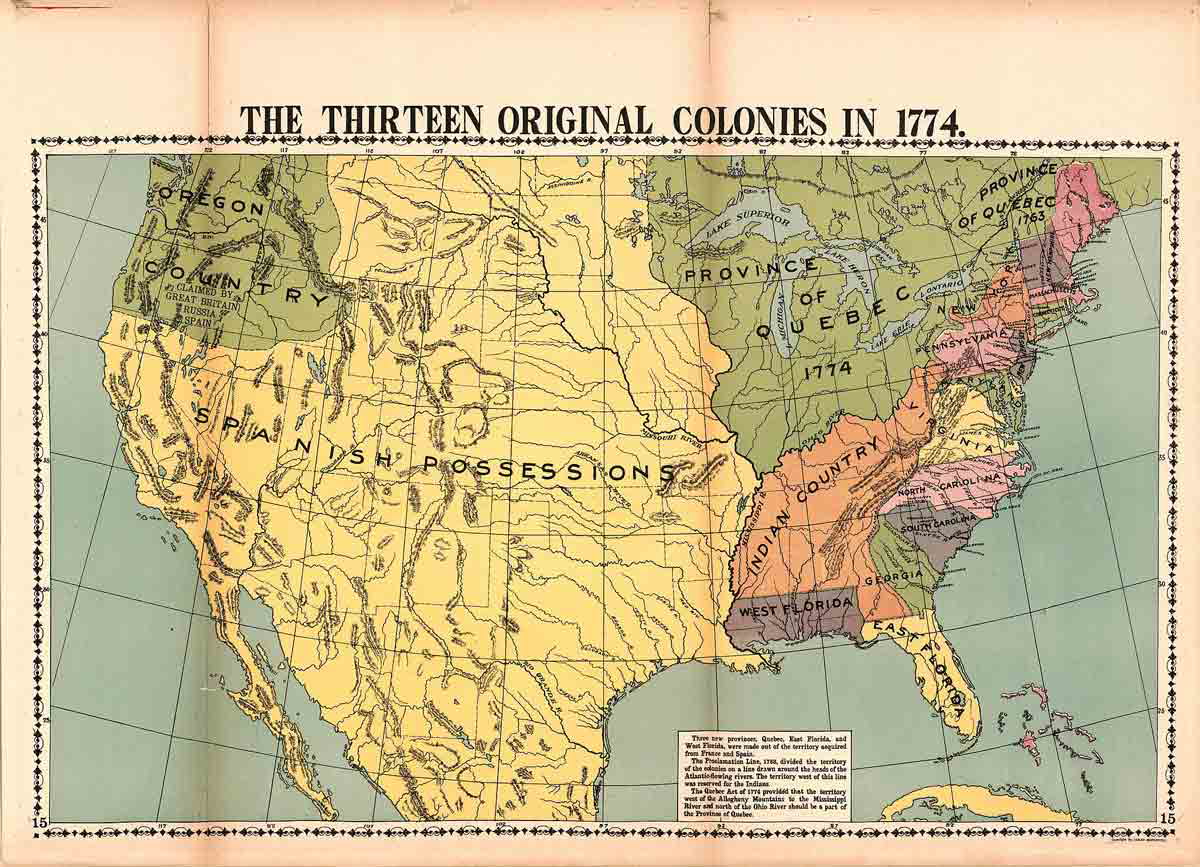

A surprising number of U.S. states owe their names to real historical figures, some well-known and others more obscure. From monarchs and naval heroes to the nation’s preeminent Founding Father, these names grace US maps as well as fill its history books. Yet, behind them hide deeper tales of power dynamics, colonial ambitions, and cultural values.

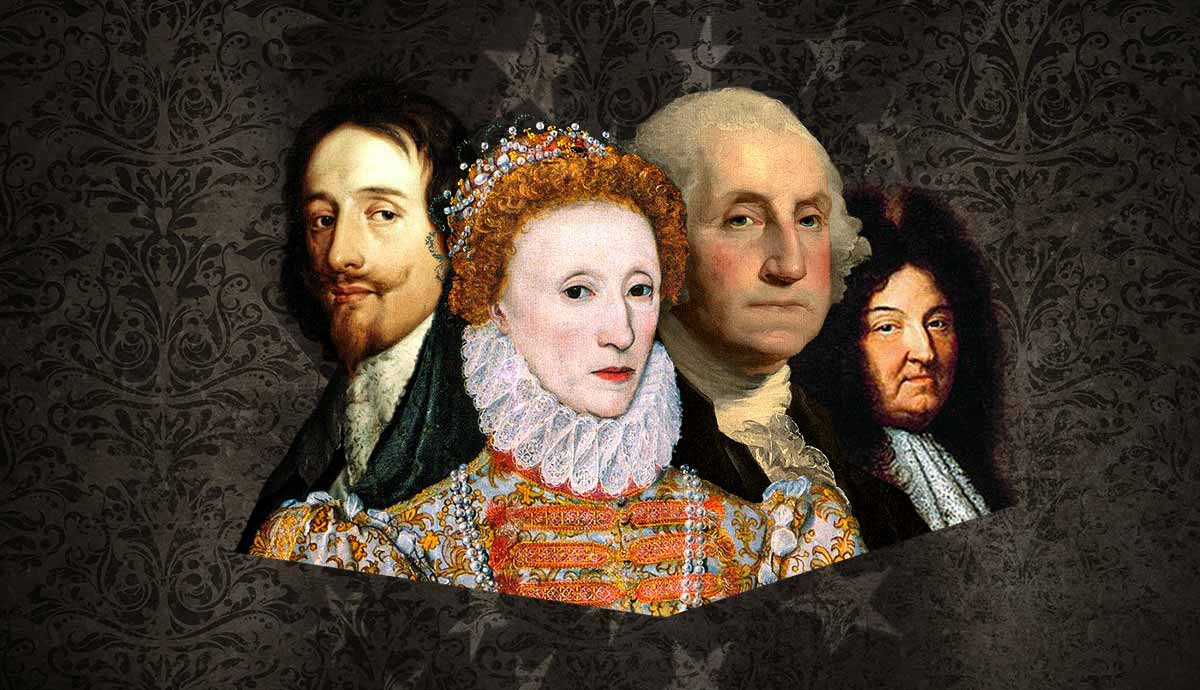

Virginia: Queen Elizabeth I

Virginia was the first permanent British colony established in the United States, so it was fitting to name it after the famous monarch who granted its charter, Queen Elizabeth I. Known as the “Virgin Queen” because she refused to marry, Elizabeth cultivated her image as a symbol of purity and national devotion and was more than happy to grant permission for the new colony to honor her title. The name “Virginia” first appeared on European maps following Sir Walter Raleigh’s use of the name in 1584. The courtier and one of the Queen’s favorite adventurers bestowed the title on the new English Colony without ever stepping on American soil, in honor and thanks to Elizabeth for granting his brother Humphrey Gilbert the charter for the expedition.

Interestingly enough, until the Virgin Queen presumably gave her blessing for the name, the British referred to their new American colony as Wingandacon—a misinterpretation of the land’s name derived from their initial encounter with the Indigenous population. The name appeared in official English documents until the more fitting one proposed by Raleigh replaced it in the late 16th century. The change was made official during Elizabeth’s reign, likely showcasing her support, when Richard Hakluyt, a well-respected chronicler, geographer, and promoter of English colonization, began using it in his published works, including 1589’s The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques, and Discoveries of the English Nation.

Similarly to Elizabeth bestowing her name, albeit indirectly, on the new British lands in America, so did the colony confer it on the first baby born across the Atlantic Ocean, Virginia Dare, a granddaughter of the governor of the ill-fated first British settlement of Roanoke.

North and South Carolina: King Charles I

The name Carolina, like Virginia, stems from an English monarch, Charles I—more specifically, the feminine variation of the Latin version of the King’s name, Carolus. The earliest use of the name appears on the 1629 patent that Charles granted his loyal supporter Sir Robert Heath, then Attorney General of England, to establish a colony in the New World. Ironically, the venture never materialized due to the lack of funding and religious restrictions against Catholic settlers whom Heath hoped to grant passage to the New World. The idea was revived under Charles’ son, Charles II, in 1660, following his father’s execution and the English Civil War between the King and Parliament.

Having reclaimed the throne, Charles II issued a new “Carolina” charter in 1663 to a group of aristocrats who had supported his return to power after a time of Parliamentary rule. Known as Lord Proprietors, the eight aristocrats intended to create a quasi-feudal society proposed by philosopher John Locke. However, geography and economics soon divided the colony into two distinct entities. Whereas North Carolina developed slowly with diminutive tobacco farms, fewer water ports, and scattered settlements, South Carolina expanded and blossomed after establishing Charleston in 1670. It promptly became one of the wealthiest colonies in America, built on rice, indigo, and the backs of enslaved laborers.

The formal split occurred in 1712, yet the two existed under the same proprietorship until 1729, when the British government purchased them from the Lord Proprietors and turned them into two separate royal colonies. Despite the change, the name Carolina remained a symbol of the restored monarchy and the Crown’s colonial reach.

Georgia: King George II

Georgia was the last of the original British colonies, and the last of the dozen original colonies formed and populated by immigrants arriving from the Old World, rather than carved out of other colonies. Unlike the other colonies’ ties to dreams of profit and religious freedom, Georgia was born out of a social experiment. Chartered in 1732 and named in honor of the reigning British King George II, who ruled from 1727 to 1760, the colony was a brainchild of a former army officer and member of the British Parliament, James Oglethorpe. The politician and a reformer envisioned a colony where the “worthy poor,” withering away in overcrowded debtor’s prisons in Britain, could receive a second chance at life.

Together with a group of philanthropists known as the Trustees for the Establishment of the Colony of Georgia in America—undoubtedly named as such to court favor for their endeavor—Oglethorpe petitioned the King for land where convicted debtors could repay their debt by building communities and avoiding the moral decay of urban poverty. With the charter in hand, the member of Parliament and 120 settlers founded Savannah in 1733. The settlers included debtors, persecuted Protestants, and other poor seeking new opportunities.

Intended to blend social idealism and military strategy by acting as a buffer zone between British colonies and Spanish Florida, Georgia hit a snag when it became apparent that its soil and climate made plantation agriculture highly profitable. The original charter favored a society of industrious farmers, banning slavery, large landholdings, and rum. Watching the success of the neighboring colony of South Carolina’s cash crop economy, the settlers demanded changes to Georgia’s strict rules. By 1752, the Trustees had given up control, and the colony’s utopian vision gave way to a market-based economy.

Louisiana: King Louis XIV

Because King Louis XIV, the Sun King, was arguably the most powerful monarch in France’s history, it was fitting to name the nation’s grand prize in the Americas after him. While an earlier expedition down the Mississippi River to find its source was unsuccessful, the 1682 endeavor by René-Robert Cavelier and Sieur de LaSalle that saw them reach the Gulf of Mexico secured for their King the rights to the entire river valley.

Standing on the banks of what today is New Orleans, La Salle proclaimed: “On the part of the very-high, very powerful Prince Louis the Great, by the grace of God King of France and Navarre, fourteenth of this name…[I have taken possession] of this country of Lousiana.” Following a ceremony at the mouth of the Mississippi River, the explorers planted a cross and buried a brass plate proclaiming the land as belonging to the Sun King. Their claim extended from the Great Lakes down to the Gulf, encompassing parts of fifteen current US states and more than 800,000 square miles.

Louisiana, or more correctly, La Louisiane (meaning “the Land of Louis”), was designed as a linchpin of France’s empire in the Americas, linking New France (modern-day Canada) to the Gulf of Mexico. Sparsely populated and thinly governed, the area became a loose network of missions and forts operated by French Jesuits and traders. Always lightly defended, France ceded Louisiana to Spain following defeat in the Seven Years’ War in 1763, to avoid losing it to the British along with French Canada.

Spain ruled the territory until 1800, when it quietly returned it to France through the Treaty of San Ildefonso. Seeking funds for his military conquests, Napoleon Bonaparte then sold Louisiana to the United States in 1803, doubling the size of the young republic.

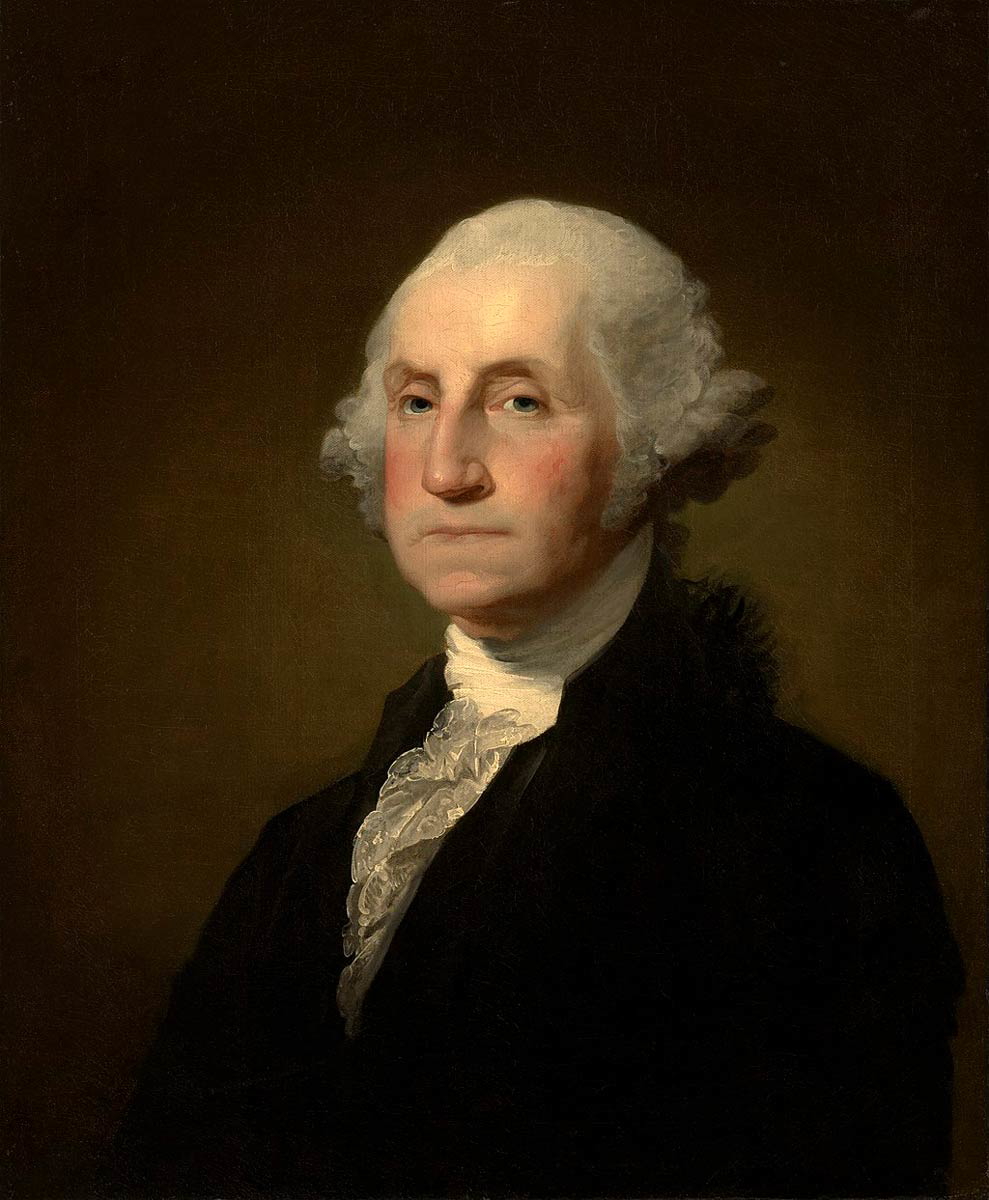

Washington: George Washington

Washington became a state relatively late in the United States’ history. In fact, by the time it was admitted to the Union in 1889, more than a century had passed since George Washington led the nation as the first president, and the name Washington was already synonymous with American ideals of republican virtue.

Because the Columbia River acted as a natural divide within Oregon Territory, and the settlers of the northern portion felt cut off from the area’s political and economic center in the south, a petition arrived in Congress to carve out the northern portion of the territory and grant it its own governance. In 1853, Congress christened the land “Washington Territory” as a tribute to the nation’s Founding Father. The symbolism was not lost on the Legislative branch members as the United States was being torn apart at the seams by sectional conflict, which would plunge the nation into the Civil War in less than a decade. Washington’s name was meant to serve as a unifying symbol, a reminder of shared origins and ideals, especially with its location in the often-contested western frontier.

The only debate and confusion stemmed from fears that its name would be confused with Washington, D.C., the capital also named after the Revolutionary War general. Ultimately, the symbolism and need for a unifying event won over, leading to Washington Territory becoming the only state named after a native-born American when it was finally granted statehood in 1889. Unlike previous states named after people, Washington’s naming celebrated democracy, merit, and American identity instead of honoring hereditary titles and noble patrons.

Lesser-Known Inspirations in the Mid-Atlantic

What separates Maryland from other early colonies named after kings or queens is that Queen Henrietta Maria, in whose honor the colony was christened in 1632, was a consort and not a reigning monarch at the time. The French-born Catholic wife of King Charles I of England never visited or influenced the colony’s founding. Terra Mariae (Mary’s Land) first appeared in the original charter granted to Cecil Calvert, the 2nd Lord Baltimore, to lend the colony monarchical legitimacy. It was also a nod to Catholicism, as Calvert envisioned Maryland as a haven for persecuted English Catholics, who shared the Queen’s religion.

The name Delaware originates from Sir Thomas West, the third Baron De La Warr, who once served as the governor of Virginia in the early 17th century. West never set foot in Delaware during his lifetime. Having arrived with fresh supplies and military leadership following Jamestown’s “Starving Time” of 1609-1610, West was widely credited with saving the Virginia colony. The following year, sailing under De La Warr’s authority, Virginia explorers encountered a body of water they decided to name after him, De La Warr’s River and De La Warr’s Bay, as a way to honor the hero of Jamestown, who at the time was the highest-ranking colonial official. Soon, the locals began calling the surrounding lands Delaware, a name that stuck when the area ultimately became a colony.

Finally, in the late 17th century, King Charles II of England owed a significant debt to the estate of Admiral Sir William Penn, a distinguished naval officer who helped restore the monarch to the throne. To settle the said debt, the King granted Admiral Penn’s son, the young William Penn, a large tract of land in the Colonies in 1681. Charles named the 45,000 square miles in the New World “Pennsylvania,” which means “Penn’s Woods.”