Utilitarianism is a moral philosophy that guides actions based on consequences—it’s about doing the best you can for the greatest number of people. But is utilitarianism really fair? Or does it just allow for an unlucky group to suffer for the majority? We will examine different areas influenced by Utilitarian ideas, highlighting both their promise and drawbacks. Can what works well in one area work even better if applied more widely?

Utilitarianism in Public Policy: Cost-Benefit Analysis

Decisions that affect millions are made by governments. But how do they figure out what is best? One big influence on public policy is utilitarianism, which has a simple goal: to do the greatest good for the greatest number while minimizing harm.

This is where cost-benefit analysis comes in. Governments weigh up the pros and cons of their policies so they can choose the ones that will make most people happiest overall.

Take healthcare, for example. In some countries, policies that determine which treatment people should receive first mean there may not be enough for everyone if resources become scarce, such as during a flu pandemic. If that happens, should we let young people go ahead of oldies in the queue for drugs such as Tamiflu?

Or environmental policies. Governments tell firms how much they can pollute for free, but some economists say this is wrong. They argue that it does not matter who cuts emissions because climate change affects everybody.

Is it truly possible to measure happiness? Simply looking at numbers doesn’t give the full picture. For example, a new law might make most people better off but ruin some others’ lives.

Is that fair? Critics of utilitarianism say that by focusing on what will cause the greatest overall good, the needs and wishes of each individual can be forgotten—or sacrificed.

So, although utilitarian calculations can help politicians face difficult choices, should they always be used when ethical decisions must be made?

Utilitarianism in Healthcare: Triage and Resource Allocation

During a medical emergency, decisions must be made about who will receive treatment immediately. Because it is impossible to help everyone at once, hospitals use a system called triage: they try to do the greatest good for the greatest number of people.

This means that patients with a better chance of surviving may sometimes be treated before those for whom the odds are not as good.

The same sort of tough choice must be made if there are not enough ventilators during a pandemic. In this situation, some people argue that younger patients should be treated before older patients, not because being old is a bad thing, but because they have had less life so far.

Similar debates go on in areas such as organ donation. For example, if there is only one liver available, should it be given to the person who has been waiting longer, or somebody else who might be able to make better use of a transplant if they become sick again afterward?

This question has been discussed by philosophers for many years. According to Jeremy Bentham, the creator of utilitarianism, the right thing to do is whatever creates the greatest amount of happiness for the largest number of people.

But is this fair? John Stuart Mill didn’t think we could measure happiness as if it were the same thing across all beings—what counts as happiness for an intelligent being, such as humans, should not be considered equal to the pleasures of other animals.

Therefore, does utilitarianism provide justice in healthcare, or does it just turn people into numbers?

Utilitarianism in Business: Ethical Consumerism and Corporate Responsibility

Businesses don’t just sell things. They have the power to change lives on a massive scale. A lot of companies take a utilitarian approach: they try to do whatever produces the most happiness overall, for customers and staff as well as society at large.

This is where corporate social responsibility (CSR) comes in. It might mean firms behaving in ways that are good for the environment, only using suppliers that treat their staff well, or giving money to charity.

For example, why might a firm start paying more money to coffee bean growers so they can have a better standard of living? Even if it means charging more for coffee. It does this because it believes paying slightly higher wages and charging a bit extra is better for society overall than the alternative.

Likewise, firms are adopting environmentally friendly practices, such as reducing plastic use. Even though these alterations may be expensive at first, they benefit both the earth and society in the long run.

But there is a downside: is this genuine morality, or just excellent public relations? Some say companies are doing what looks nice (and keeps profits rolling in) by utilizing utilitarianism.

For instance, businesses may decide to substitute artificial intelligence (AI) for human employees to become more cost-effective. From a consumer’s perspective, this is great because prices fall, but does it pass ethical muster?

The philosopher John Stuart Mill raised a red flag about people misusing utilitarianism for their own ends. So, are business folks who deploy the theory acting morally, or just pretending to be good guys?

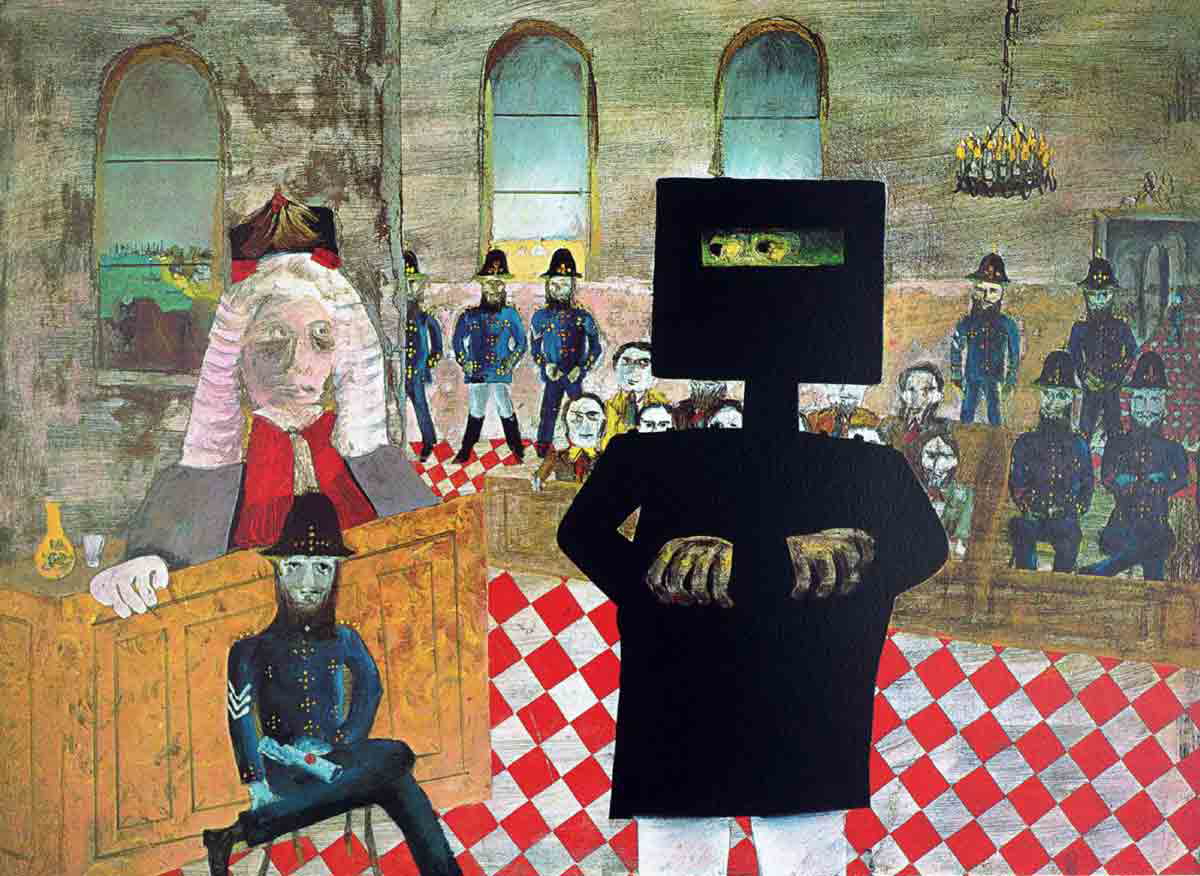

Utilitarianism in Criminal Justice: Sentencing and Punishment

Should punishment be about justice, or should it be more concerned with the greater good? In criminal justice, utilitarianism is a major player. It affects laws, how long we put people in prison, and what goes on there. Why? Because it aims to make crime levels drop and keep society safe, while raising some tough ethical issues.

Take deterrence as an example. This theory is based on the idea that imposing harsh penalties stops individuals from breaking the law. After all, if you don’t want to end up behind bars (or worse), then you’re less likely to commit a crime.

Sometimes, the death sentence is defended using this logic: if one condemned killer can be executed, that action will prevent many other innocents from becoming victims in the future.

But is it fair? Let’s say we punish someone who hasn’t actually done anything wrong because we believe it will make society safer overall.

Unlike others, some states favor rehabilitation over punishment. They do not believe in long prison sentences. Instead, they provide education and counseling with the goal of helping offenders become law-abiding citizens.

Norway provides a case in point. The country’s jails are so progressive that they offer vocational programs. Why? Because a reformed individual has greater worth outside incarceration.

Still, there are instances where one person’s freedom puts others at risk. Utilitarianism seeks to weigh an individual’s rights against society’s needs—a difficult job by any measure. Must fairness be sacrificed for the greater good (whatever that may mean)—or does morality require a different course altogether?

Utilitarianism in Technology: AI Ethics and Data Privacy

Life is made more convenient thanks to tech, but at what cost? In AI and data-driven decision-making, the rule of thumb is utilitarianism: always pick whatever benefits the most people, even if it hurts someone.

Take self-driving cars. Say there’s a crash and it can’t be stopped. Who should the car protect: its own passenger or people outside? Going by utilitarian logic, it should do whatever causes the least harm overall.

But what if that means saving three passengers by swerving into the path of an oncoming vehicle and killing its lone occupant instead? This kind of choice would be acceptable to Jeremy Bentham, but does it imply that one person’s life is worth less than others?

An additional utilitarian problem involving data privacy is presented. Firms collect personal details to enhance services, suggest content, and stop scams. The greater the amount of data amassed, the better their systems work—but this is achieved by sacrificing some privacy.

Do companies really require all this information about us if it merely exists for things to be made more convenient? As John Stuart Mill cautioned, there might always have been reservations about sacrificing individual liberty for the general good.

It remains uncertain whether utilitarianism does nothing more than boost technological efficiency at the expense of human rights, or whether, in doing so, it also erodes them in the name of efficiency.

We are still trying to strike a balance between ethics and progress, and never before have such high stakes been placed on getting it right.

Utilitarianism in War and National Security: The Ethics of Collateral Damage

Governments use utilitarianism to morally justify the cruelty of war. They want to achieve the greatest good for the greatest number—even if that involves doing something bad.

Consider drone strikes. The authorities send them out to kill terrorists before they can attack again: one missile could save hundreds or thousands of lives. But what if innocent people die, too?

Utilitarians would say their deaths were a price worth paying for preventing more harm. Jeremy Bentham might well have agreed with this justification. After all, keeping citizens secure is a key function of government.

However, other thinkers might point out that it is never acceptable to kill someone who is not a threat, regardless of how many other individuals this action may protect

An example of this is seen in times of war. For instance, Hiroshima and Nagasaki were bombed at the end of World War II. Many thousands of civilians died, but it brought about a quicker end to the conflict, saving even more lives.

Nevertheless, can we say that an action is right just because it has good consequences? The philosopher John Stuart Mill wrote of harms that cannot be measured against one another.

Another case is torture during counter-terrorism operations. There are those who think it is acceptable to hurt one person if it will save many others, for example, by getting important information out of them.

Is such behavior really fair, or does it show that we are no better than our enemies? If we do allow some types of harm, after all, where should we draw the line?

So, What Is Utilitarianism in Practice?

Utilitarianism is found in government policy, medicine, business, technology, and even warfare. It gives us an understandable and rational way to bring about the most happiness and minimal harm, and it can be an effective decision-making tool. But we know it is by no means perfect.

Although utilitarianism can be helpful to societies in making tough choices, it raises some serious ethical concerns. Can we really measure happiness? Is it fair to trade off some for the common good?

Its strongest feature is its pragmatism—it allows organizations and leaders to make decisions with real-world consequences. But its weakest feature? It disregards individual rights and ethics for the sake of numbers. It was against such blind following of numbers when human dignity is at stake that John Stuart Mill warned.

So, can utilitarianism be a solution? Or does its focus on the greater good come at too great a price? Perhaps morality is more than simply balancing outcomes—it’s about protecting what makes us human.