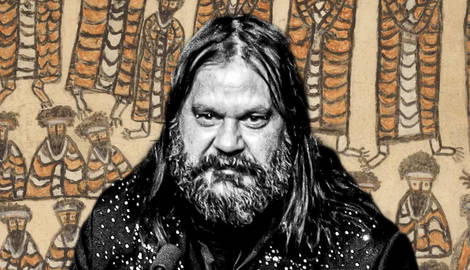

In November 2023, The New Boy (2023), the latest film by Kaytej Aboriginal filmmaker Warwick Thornton, won the top prize at the Camerimage, the International Film Festival of the Art of Cinematography held annually in Torún, Poland. For over two decades, Thornton has been writing and directing features and documentaries that explore Aboriginal identity, trauma, and the place of Aboriginal people in contemporary Australian society. That very same society that for too long has deliberately ignored the perspective of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders. His work addresses the complexities of the relationship between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians, as seen in Sweet Country (2017). In another powerful film, Samson and Delilah (2009), he portrays young love within the context of remote and disadvantaged Aboriginal communities intoxicated by petrol-sniffing.

Who Is Warwick Thornton?

“I am an Indigenous artist,” Warwick Thornton once said. “I could get rid of the art. I could be a plumber or an electrician. But I can’t just wash away being Indigenous and I wouldn’t want to. And it’s all art to me.” A Kaytej man, Thornton was born and raised in Alice Springs, in the Northern Territory, on lands that have belonged to the Arrernte people since time immemorial. His ancestors used to live around Tennant Creek and Barrow Creek, about 300 kilometers (186 miles) north of Alice Springs, not far from the lytwelepenty/Davenport Ranges National Park in Australia’s Red Centre. In addition to being a filmmaker in the most literal sense—he is a writer, director, and cinematographer—Thornton is also an acclaimed photographer.

In his 2015 exhibition, The Future is Unforgiving, he photographed various Aboriginal children, the future of Aboriginal society and culture, wearing suicide vests made of beer cans, Coca-Cola cans, fast food containers, and black tape. The suicide vests are strapped to their torsos, but the only lives that are endangered are theirs, threatened by obesity, alcohol abuse, sugar, and fast foods. The burden of social and historical injustices, the damage caused by decades of colonialism, and the innocence of these young victims are central to many of Thornton’s films, from Samson and Delilah (2009) to his latest The New Boy (2023). Written and directed by an Aboriginal author deeply in touch with his Aboriginality, Thornton’s films reflect on Australia’s colonial history and offer a truthful and painful perspective on Aboriginal society, on what it means to be Aboriginal Australian in today’s world, particularly in the aftermath of the disastrous results of the 2023 Australian Indigenous Voice referendum.

Sweet Country

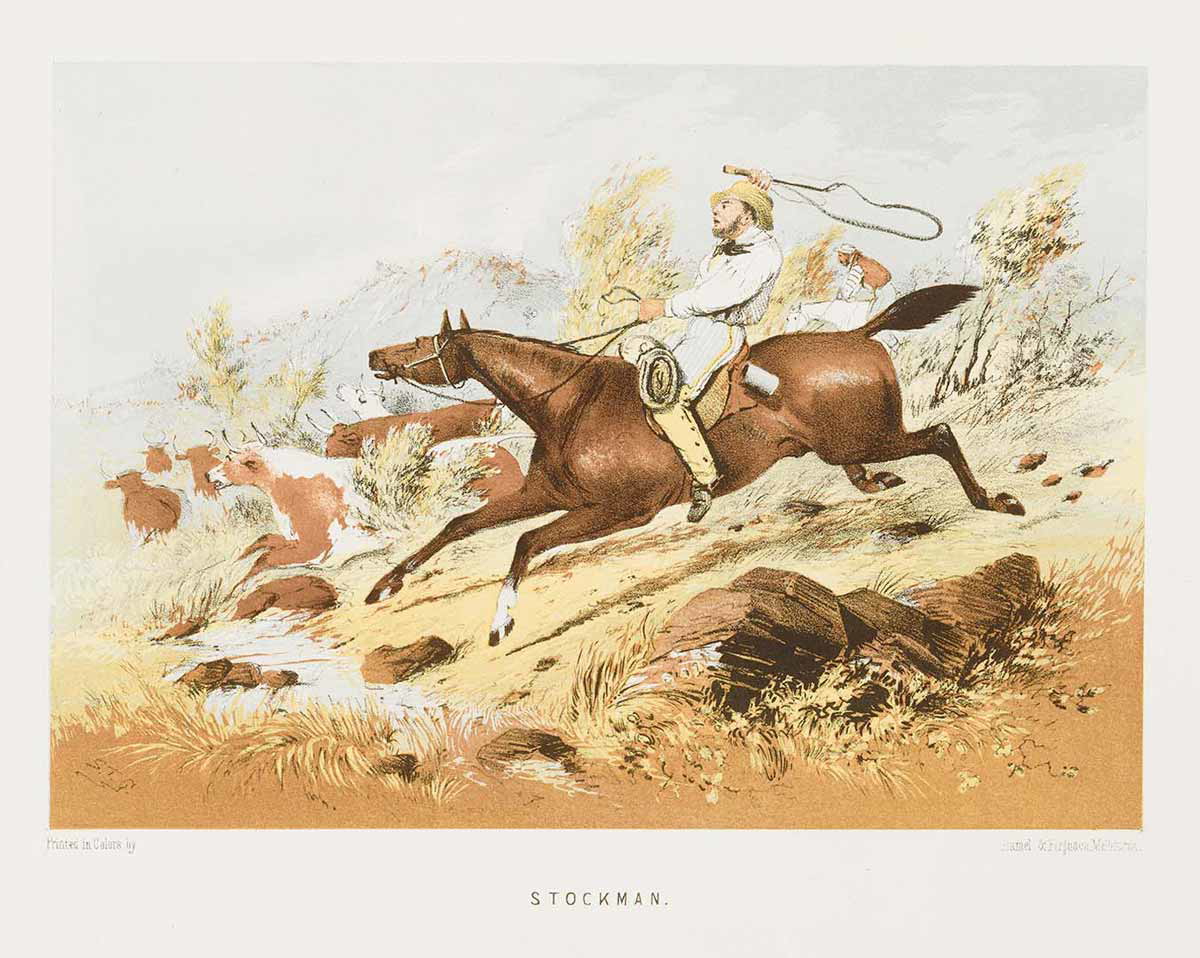

It is the 1920s, and Sam Kelly (Hamilton Morris) is an Aboriginal stockman working and living on the property of Fred Smith (Sam Neill) with his wife Lizzie (Natassia Gorey-Furber). He is a hard-working man, a man of principle who enjoys a friendly relationship with his boss. Then he kills his neighbor, Harry March (Ewen Leslie), in self-defense. As March, a violent, rapist, and alcoholic veteran of World War I suffering from PTSD, bleeds to death under the scorching Australian sun, amidst dust and mosquitoes, Sam and Lizzie flee into the Outback, a territory they know better than anyone else. And so their epic begins.

Sweet Country was shot primarily at Ooraminna, a cattle station west of Alice Springs, on the ancestral red and remote lands of the Aranda people, near the Tjoritha/West MacDonnell National Park. Thornton’s film is as much a Western as Penn’s Little Big Man (1970) is a Western.

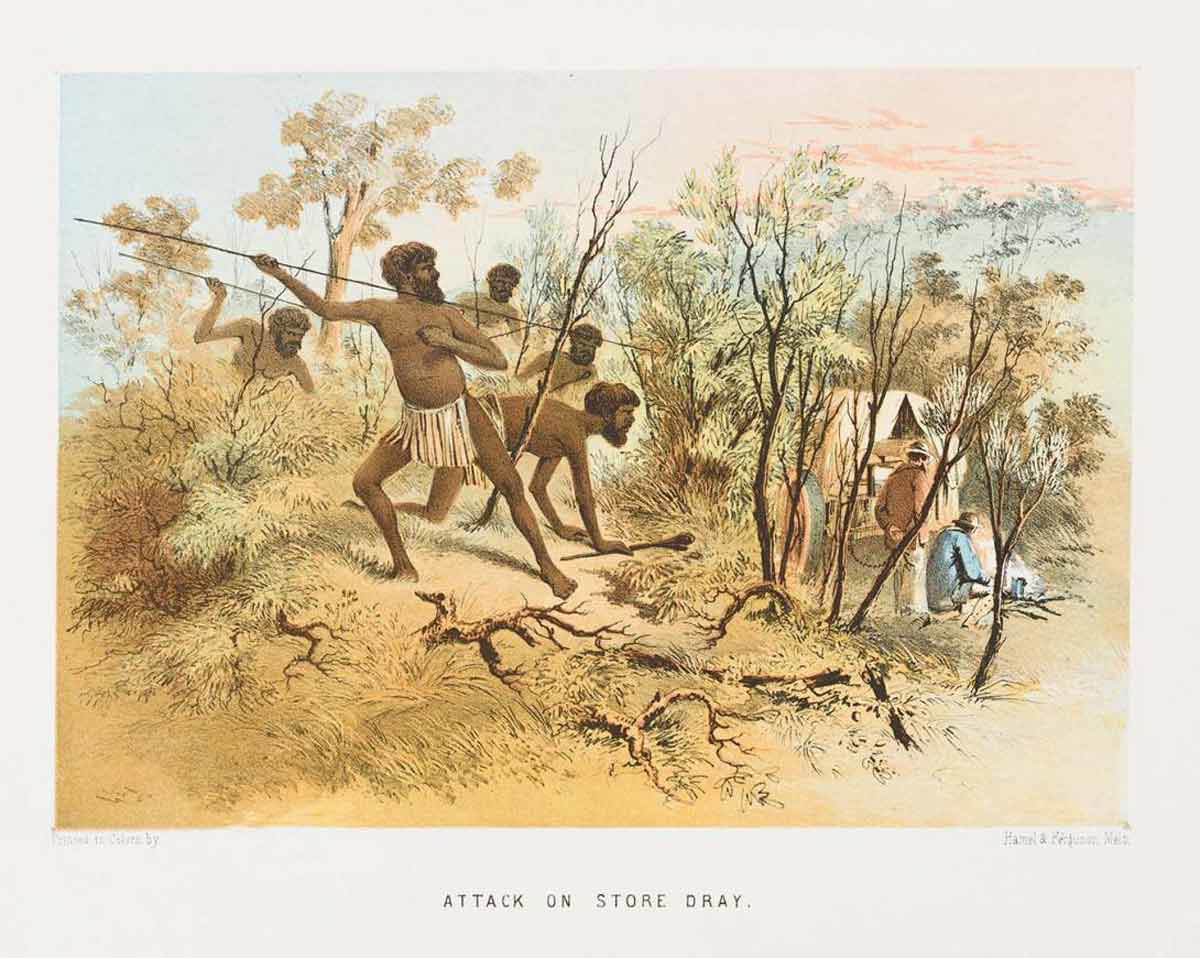

Both are revisionist Westerns that exploit the traditional tropes of Westerns to discard accepted national narratives, narratives that have contributed to a stereotypical representation of Indigenous peoples and silenced and marginalized their voices for decades. Sam Kelly and his wife Lizzie are painfully aware that in the society they live in the word of an Aboriginal woman doesn’t stand a chance against that of a white man. Sweet Country’s Australia is a country divided along race lines, a hurting country unable (and unwilling?) to protect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders and grant them the decency of fair treatment.

Is contemporary Australia any different from 1920s Australia when it comes to race relations, equality, and justice? Has the situation of Aboriginal people improved compared to 100 years ago? Have non-Indigenous Australians learned to regard Aboriginal Australians with the same degree of humanity they accord to themselves? These are the questions that Sweet Country, particularly the film’s stunning ending, leaves us with.

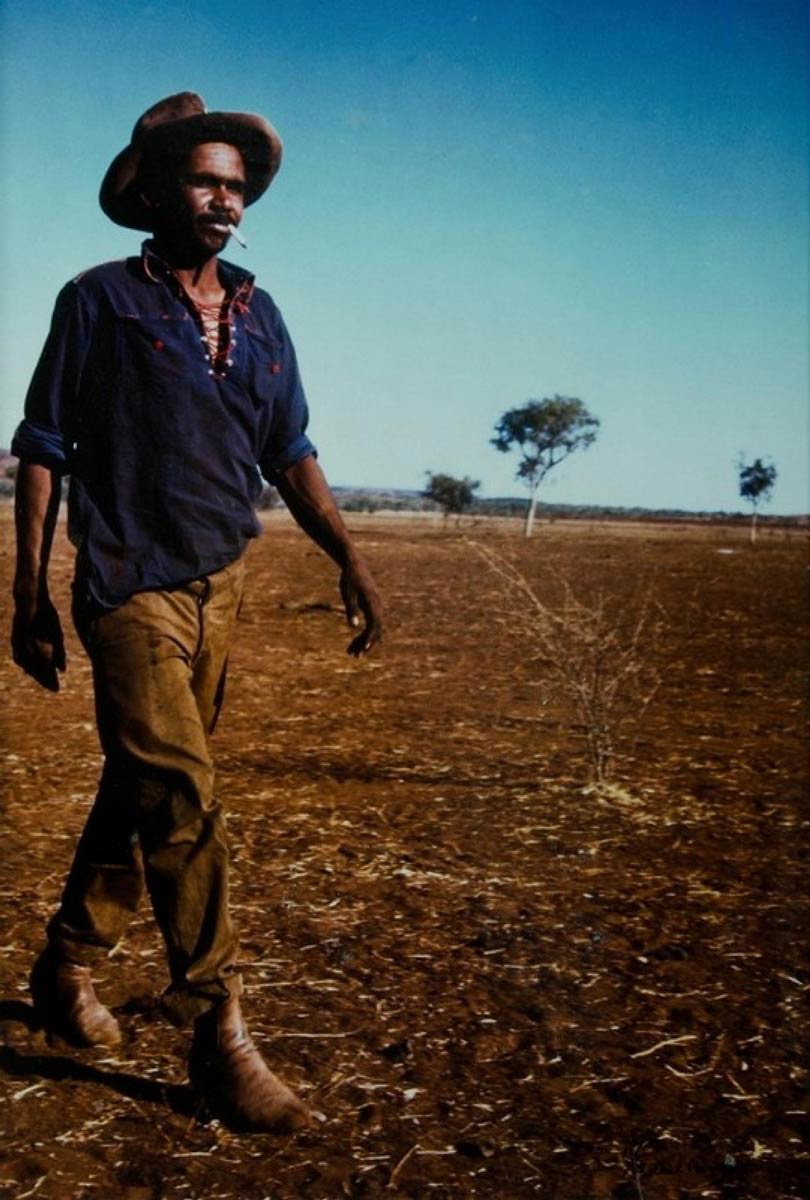

Stockmen in Australia

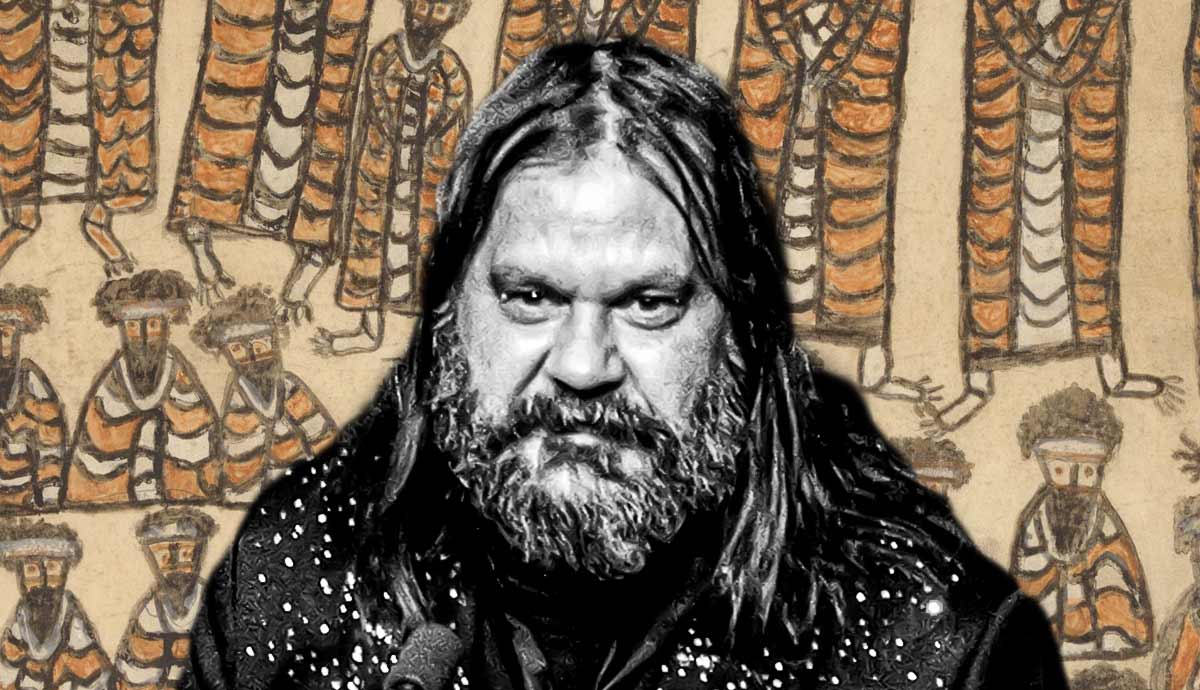

Sweet Country is a powerful revisionist Western film. It is also a celebration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders’ unique relationship with the country of their ancestors, a relationship that has evolved over the years and has managed to adapt to the upheaval brought about by colonialism. At a time when Aboriginal children were forcibly removed from their families, placed in residential schools, and not allowed to speak their parents’ language, at a time when Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders continued to be displaced, facing racism and discrimination, there was a (relatively) safe place in Australian society where Aboriginal man and women could preserve their culture and languages. This place was the cattle station, typically a large landholding with an extensive range of grazing land where the grazier (the property owner) could rear cattle, a homestead, and some cottages for the employees.

Since the 19th century, cattle stations have been the backbone of Australian industry. They have also played an important part in preserving Aboriginal languages and traditions, as they provided, to put it with Richard Broome, author of Aboriginal Australians: A History Since 1788, “a breathing space for Aboriginal culture.”

Historically, the impact of British colonialism was most significant on Aboriginal groups in the southern regions of Australia, specifically in present-day New South Wales and Victoria. In the country’s northern regions, however, every year Aboriginal stockmen and stockwomen employed by landowners and cattle barons embarked on long droving trips on horseback through the Outback. It was here, in Queensland and the Northern Territory, in some of the world’s driest regions, that they cyclically renewed their connection to their ancestral lands, to the stories and languages of their ancestors.

To quote from Ann McGrath, author of Born in the Cattle: Aborigines in Cattle Country, “generations of Aboriginal station dwellers co-operated with white people, but they were never really colonized… They incorporated different animals, technologies, skills, and kin into their cultural landscape, but it remained their country, their world.”

Despite being coerced, low-paid, denigrated, and often physically abused, many Aboriginal workers embraced cattle work with pride, infusing it with their traditional practices, with their abilities to locate bush tucker, animal tracks, and waterholes. In his Sweet Country, Warwick Thornton shows us the pride of an Aboriginal stockman, Sam Kelly, who removes himself from a society that denies him his rights and refuses to consider him equal to men and women of European descent. Kelly tries to find peace and safety in the bush, but to no avail.

Samson and Delilah

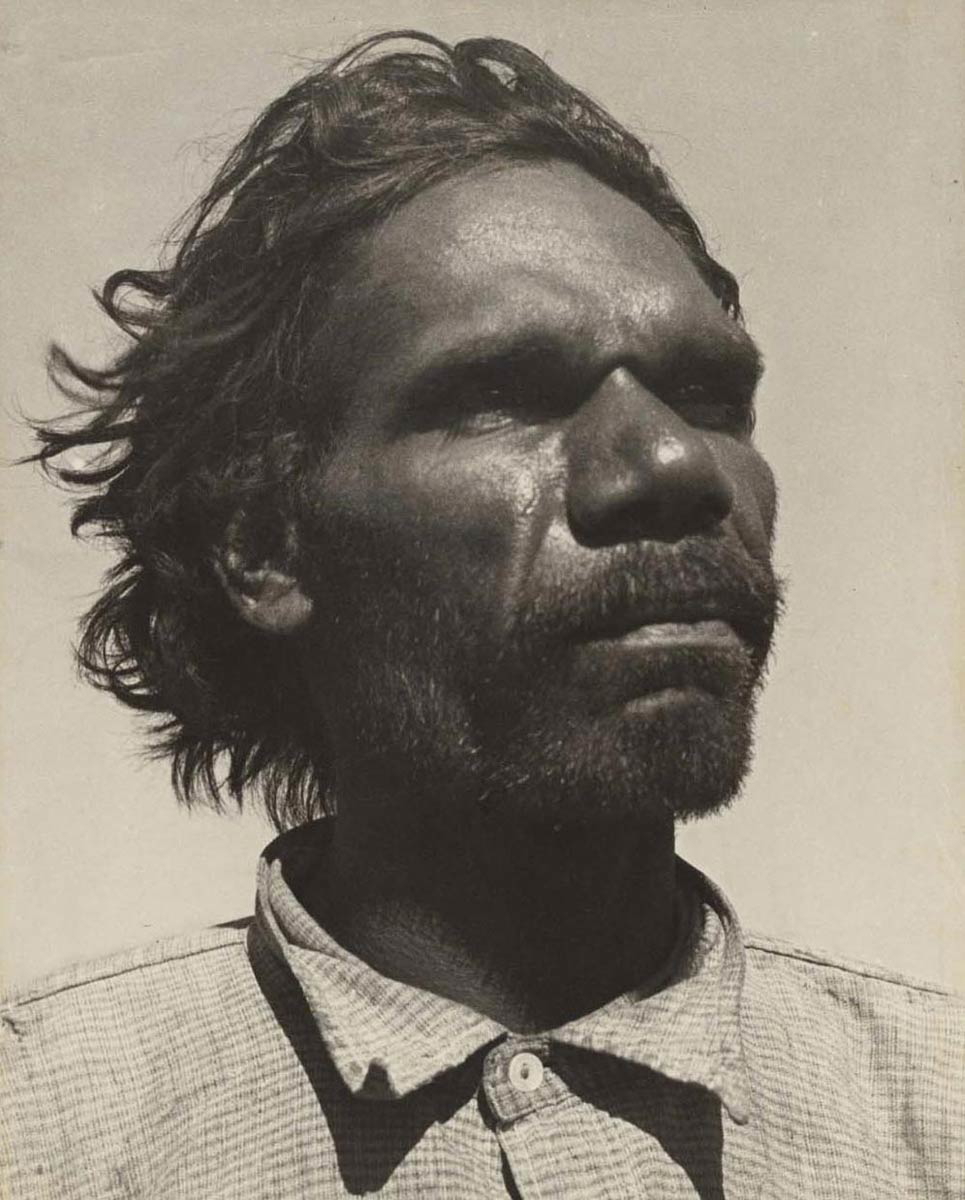

Samson and Delilah is Thornton’s directorial debut. The film revolves around two 14-year-olds, Samson (Rowan McNamara) and Delilah (Marissa Gibson), living in a remote Aboriginal community in the Australian Red Centre. The closest town is Mparntwe—Alice Springs, as it is known among non-Indigenous Australians. In the language of the Arrernte, Mparntwe (pronounced m’barn-twa) translates to “watering place.”

When Delilah’s grandmother, Nana, suddenly dies, Delilah jumps on Samson’s stolen car and heads with him to Alice Springs. They don’t talk much, but there is a sense that they can rely on each other. In Alice Springs, their lives intersect with a constellation of different figures—Gonzo, an Aboriginal homeless man played by Scott Thornton; a group of white teenagers who abuse Delilah; and the silently racist white inhabitants of Alice Springs.

There is despair in Samson and Delilah, but there is also hope. Above all, there’s determination. Determination to survive. Determination to silently (and proudly) claim one’s place in a society that accepts Aboriginal people only—and not even always—within certain spaces, specifically, that of Aboriginal art. This is exactly how Delilah tries to survive in the city—by selling Aboriginal paintings—before returning to the bedding she shares with Samson under a bridge on the dry bed of the Todd River.

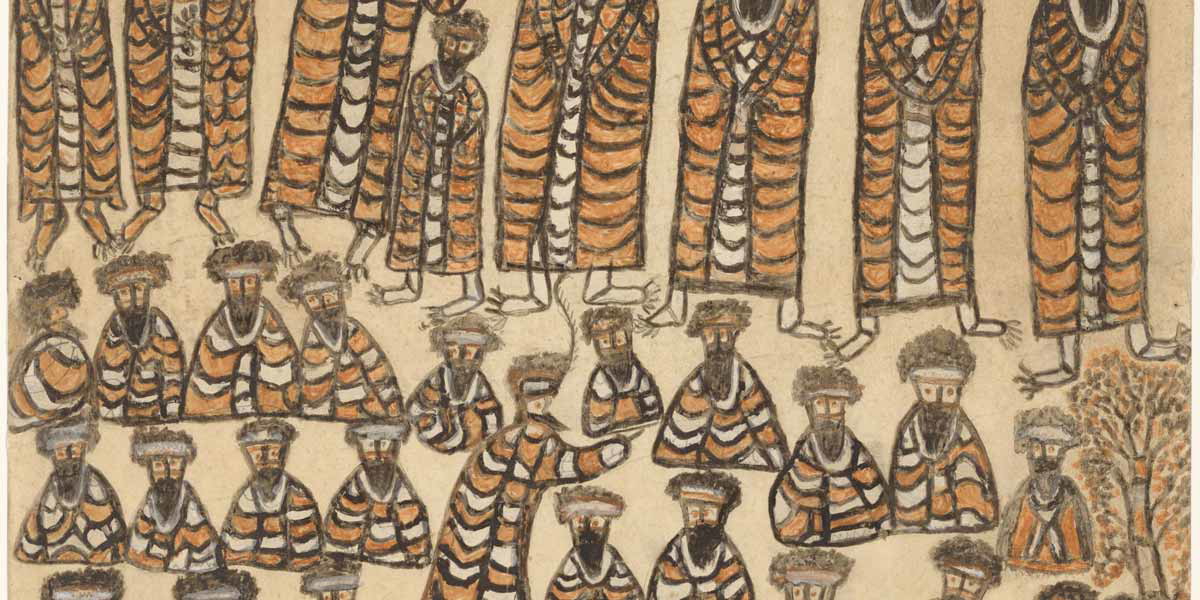

Samson and Delilah’s silent determination is, indeed, fuelled by art and human affection. Delilah’s grandmother, Nana, for instance, is a painter. The fact that her character is played by Pintupi actress Mitjili Napanangka Gibson (1932-2011), who is also one of Australia’s most revered Aboriginal painters, adds a poetic touch of realism. Samson’s brother is a musician. His band plays ska music all day in their run-down shack. And although Samson is their only spectator, their energy is contagious.

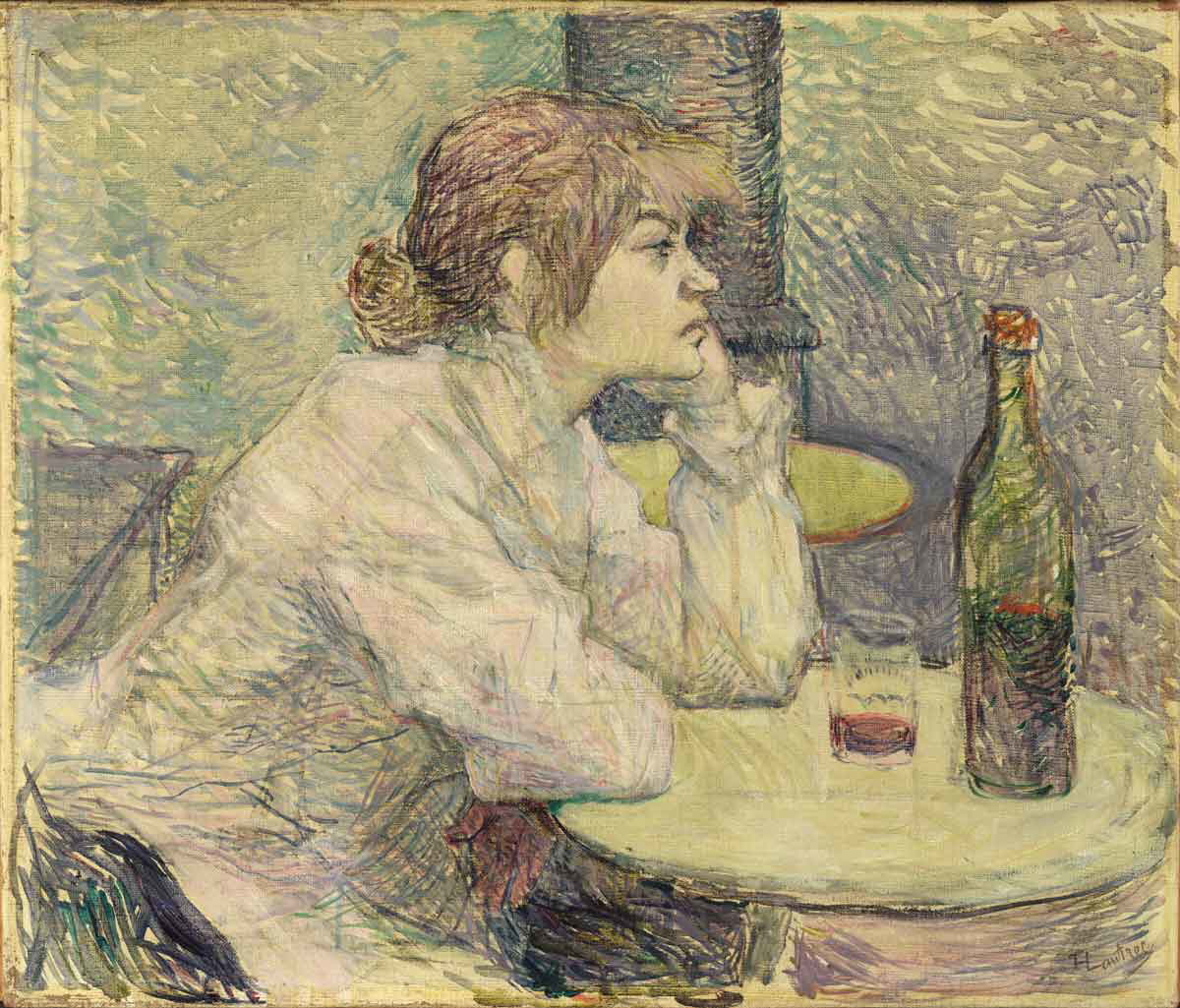

The Coming of the Grog

The society depicted in Samson and Delilah is still struggling with the consequences of the introduction of the grog—a slang term for any alcoholic beverage—in Aboriginal communities. Thornton is not the first Aboriginal artist to discuss the impact of the grog on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, particularly those living in the Outback, removed from any form of social assistance.

In her Grog War (1997), for instance, Waanyi award-winning author Alexis Wright recalls the history of a small community in remote Australia fighting against the “invasion of the grog.” In his novel Taboo (2017), Noongar author Kim Scott depicts a tight-knit community working to “come back to life,” to rebuild and strengthen its connection to its ancestors’ lands and history. A community whose survival can’t be taken for granted, as it is fragmented and torn apart by alcohol addictions, violence, and drugs.

A similar sense of tenaciousness mixed with despair can be found in Samson and Delilah. In the 1950s and 1960s, the strict Australia-wide ban rules on Aboriginals drinking alcohol were lifted. Communities already struggling with severe poverty, unemployment, and dispossession-induced depression suddenly had unlimited access to alcoholic beverages of any kind. The consequences were devastating. Alcohol abuse and binge drinking have been plaguing Aboriginal communities ever since, resulting in increased rates of premature death, domestic violence, sexual abuse, mental health issues, unemployment, and isolation.

Historically, Australian authorities have used the devastation caused by the grog among Indigenous communities to control the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders across the country. In the Northern Territory, for instance, many Aboriginal communities are designated as “dry communities,” where alcohol consumption and possession are prohibited.

In a 2019 article for The Guardian, Claire Coleman, an Aboriginal Australian author with Wirlomin and Noongar ancestry, perfectly described how Australian authorities have used alcohol as a means to curtail Aboriginal civil rights and freedom since the 2007 Intervention, also known as the Northern Territory National Emergency Response. “On my way to Kalkarindji, NT, for the festival celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Wavehill Walkoff in 2016,” Coleman writes, “I was pulled over by about 20 police officers in something like 10 Landcruiser Troopcarriers who were checking every car for alcohol. I have never lived in a dictatorship but after that experience, I can imagine what it would feel like.”

Commenting on his aforementioned photographic work The Future is Unforgiving, Warwick Thornton echoed Coleman’s words when he stated that “we’re all dying from bad food, not from terrorists, […] the ticking bomb is bad diet, bad stuff that we get fed every day, which is legal.”

In Samson and Delilah, while the white inhabitants of Alice Springs enjoy their drinks outside coffee shops and restaurants, Samson and Delilah are shown sniffing petrol under a bridge over the dry bed of the Todd River. Petrol sniffing is a different kind of “grog,” but its disruptive, long-lasting consequences are turning Aboriginal communities into a wasteland of despair, poverty, and hopelessness.

When Delilah is hit by a passing car, Samson is too intoxicated to notice. When he finally realizes that she’s gone and probably won’t come back, he cuts off his hair. As a form of respect, as it has been noted, or as a form of ultimate desperation. Hair is a significant connection to one’s country and community. Recent analysis of mitochondrial DNA from 111 hair samples collected across Australia over half a century (from the late 1920s to the 1970s) has revealed that Aboriginal Australians have continuously inhabited the Australian continent for approximately 50,000 years.

Delilah, however, comes back. She is a survivor, just like Samson. Her return brings us to the essence of Samson and Delilah. At its core, this is a film about people helping (or trying to help) each other out and about the determination to nurture an overarching sense of community. Delilah, for instance, is shown taking care of her grandmother. In his own way, Samson takes care of Delilah when Nana dies. Delilah rescues Samson from the streets of Alice Springs and takes him back to their remote community in the desert where he will try to overcome his addiction.

Re-Affirming Aboriginal History

In her article for The Guardian, Claire Coleman writes: “There are many places in Australia where grog has been banned through the decision of the traditional owners, I accept that. This is about a government, about successive governments, who believe they have the right to control Indigenous affairs. This is about white supremacy and a country that does not believe First Nations people deserve, have not the maturity, to manage our own affairs.”

Thornton’s films, from Samson and Delilah to Sweet Country and The New Boy, reaffirm Aboriginal rights to self-determination by openly discussing the problems that plague Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders in the past and the present. Therein lies the strength of Thornton’s work: he calls on both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians to face the hard fact that for far too long Aboriginal Australians have been treated as second-class citizens, unable to survive without the help of Australian authorities.

Telling honest and ruthless stories set in the present and the past, Thornton also questions what it means to be Australian today. How can we define Australian identity? What does it mean to be an Aboriginal Australian in a country that still does not believe, to quote Coleman, that “First Nations people deserve, have not the maturity, to manage our own affairs”?

What does it mean to be an Aboriginal Australian in a society that all too often chooses to ignore the despair and the depression affecting young and old alike and ultimately leads them to petrol sniffing and alcohol abuse? Ultimately, Thornton’s films reaffirm Aboriginal history and the right of Aboriginal people to tell their own story and the story and culture of their people in their own words, free from the imposed mediation of non-Aboriginal Australians and Australian cinema.