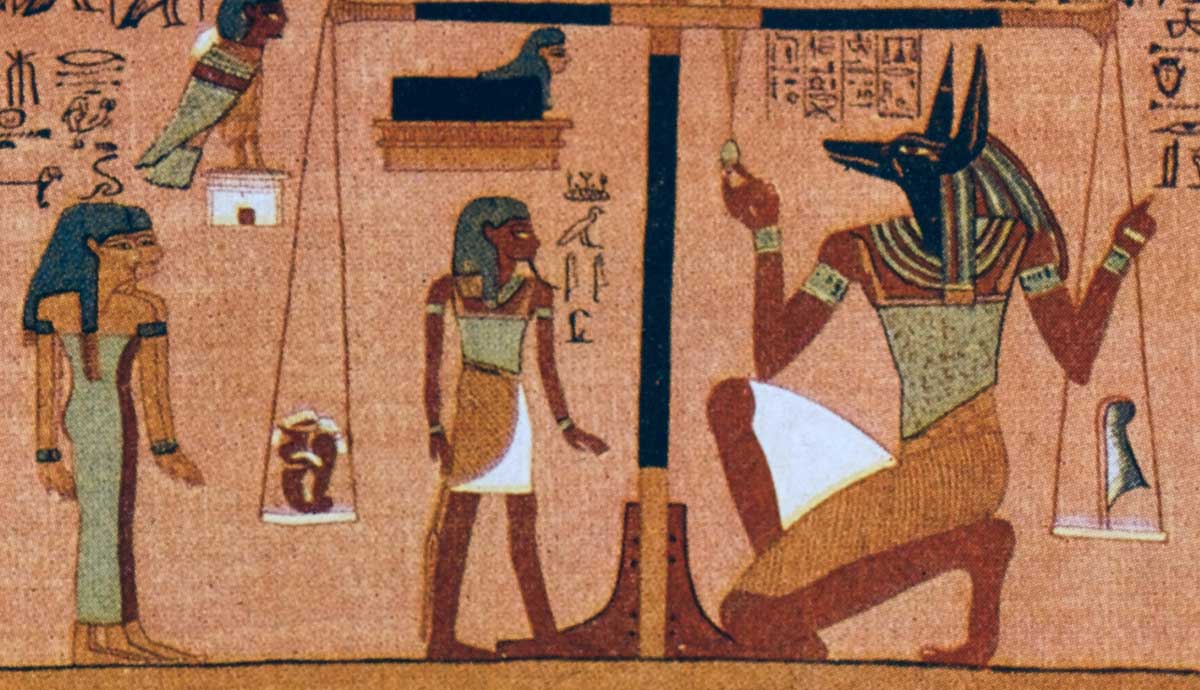

One of the most famous scenes surviving from ancient Egyptian art is the Weighing of the Heart Ceremony, during which the heart of the deceased was weighed against the feather of Ma’at. If the heart was lighter than the feather, they passed into ancient Egypt’s paradisical afterlife. If it was heavier than the feather, they were devoured by the monster Ammit and resigned to oblivion. This belief was so important to Egyptian culture from at least the New Kingdom onwards that it was immortalized in Egypt’s most common literary text, the Book of the Dead.

Precursors to the Book of the Dead

The Egyptian Book of the Dead is the name given to the ancient Egyptian funerary text from the New Kingdom that has inspired much of our modern perception of ancient Egypt. But this prominent collection of texts was the last iteration of religious narratives relating to the afterlife that had been present and adapted since the Old Kingdom.

The original Pyramid Texts date back as far back as 2400-2300 BCE and were a compilation of incantations intended to help the dead pass into the afterlife. Written on the walls of pyramid burial chambers, these texts were reserved only for the pharaoh (and sometimes his queen) and had no accompanying imagery like the renowned vinaigrettes from the Book of the Dead.

The Pyramid Texts evolved into the Coffin Texts, which appeared around the start of the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181-2055 BCE). The major cultural shift was that if you could afford a coffin, you had access to these spells. In conjunction with this new change, the ideals of the afterlife expanded to include the life challenges of ordinary people. The collection of spells included prayers designed to help the dead avoid disagreeable tasks such as manual labor and also to evade fearsome supernatural beings and traps.

Democratizing Access to the Afterlife

From around 1550 BCE, the Book of the Dead, which was known by the ancient Egyptians themselves as The Book of Coming Forth By Day, came into use. This groundbreaking piece of literature was a corpus of rituals, spells, prayers, and general guidance on navigating the afterlife based largely on the two preceding compositions. In this adaptation, collections of texts chosen were inscribed onto papyrus, written on sarcophagi, on the walls of tombs, or on objects buried with the dead, often illustrated with vivid accompanying scenes.

Moreover, the text was never canonical, and many wealthy individuals seemingly had their own personalized versions, which were perhaps based on the spells they valued most out of the 192 known to us today. Yet, most included some reference to the Weighing of the Heart ritual.

This stage of the journey through the afterlife was often one of the final barriers before the deceased could reach the “Egyptian Field of Reeds” or the “A’aru.” The A’aru is often compared to the Christian concept of heaven, as it was described as a paradisical version of the world of the living, and access requires a pure heart.

The Heaviness of the Heart

In ancient Egyptian culture, the heart or “ib” was seen as the most important organ in the body. Interestingly, it was one of the only organs left or reinserted into the body during the mummification process. The heart not only recorded an individual’s deeds, whether good or bad, but also it was the core of a person’s being, comparable to the modern idea of the soul. The heart was considered the base of emotions, intellect, and memory. Due to this, it played a key part in entering the A’aru.

A heavy heart would bring about tragedy after death. Someone who had greatly sinned during their lifetime would carry this in the weight of their heart. Therefore, when it came to weighing the heart against the feather of Ma’at, it would undoubtedly weigh more and the person would not be allowed into the Field of Reeds. Misbehaviors such as jealousy and ungratefulness would leave their mark on the heart, and it would be eaten by the monster Ammit.

If a person had righteously lived their life, this too would be reflected in the condition of the heart and it would be lighter than the feather or balance the scales. A person would possess a light heart if they maintained the values associated with Ma’at, such as harmony and justice, namely by expressing appreciation for what they had been given in life. The white feather of Ma’at represented both the concept and the goddess of the same name and possessed the ability to only let virtuous and moral people into an eternal afterlife.

Standing Before the Judges

After the deceased had traversed the landscape of the underworld, along the way avoiding otherworldly entities and supernatural snares, they would be led by Anubis to the Hall of Truth, sometimes known as the Hall of Two Truths. Here, the deceased would join a queue of souls where some goddesses, notably Qebhet, daughter of Anubis, would comfort them before their turn to stand in front of Osiris.

When it was time, Anubis would lead the soul into the Hall of Truth in front of Osiris, Thoth, Ma’at, and the 42 minor deities tasked with determining the fate of the dead. These gods and goddesses are typically named the 42 Assessors of Ma’at, and all presided over a single sin that those wishing to pass to paradise should not have committed. For example, Am-khaibit is concerned with murder, Qerrti is concerned with adultery, and Nehebkau is concerned with arrogance.

The individual had to declare themselves innocent of all the crimes against Ma’at that each of the deities was in charge of punishing accordingly by reciting the 42 Negative Confessions. Each confession started with “I have not…” or “I did not…”. This process was to gain the approval of the 42 lesser deities. However, there was no complete list of sins and, correspondingly, no complete list of the Assessors of Ma’at. The pantheon of judges appeared differently in different versions of the Book of the Dead.

While the 42 Negative Confessions were important, Osiris made the final decision about the fate of the deceased soul based on the weighing of the heart against the feather of Ma’at.

Significance of Osiris

The importance of Osiris can be felt throughout ancient Egyptian society and culture, not just in the journey to the afterlife. He rose to even greater prominence in the New Kingdom as access to the underworld he ruled was democratized. The Osiris myth, an extended part of the ancient Egyptian creation epic, survives in written works from the Old Kingdom in the 24th century BCE.

In the creation myth, Atum or Ra, the creator sun god, emerged from chaotic water and produced Shu and Tefnut, the deities of air and moisture, respectively. From their partnership Geb, the sky god, and Nut, the earth goddess, were born. These two siblings also paired and created Osiris, Isis, Set, and Nephthys. Osiris and Isis became a sibling couple and Set and Nephthys did the same. These two unions became the most powerful beings in Egypt.

As the eldest sibling, Osiris was the King of Egypt, and Isis ruled as queen. In the story, not much is said of Osiris’s rule other than that he ruled with the power of Ma’at, and therefore, with his murder at the hands of his brother, Set, the order of Ma’at was destroyed. The myth goes on to describe how Isis and Nephthys resurrected Osiris by effectively turning him into the first mummy.

After Osiris was brought back to life, Isis became pregnant with their son and now rightful heir of Egypt, Horus. He went on to contend with Set for the throne. Meanwhile, Osiris became the ruler of the Duat or Egyptian underworld, which the deceased passed through to get to the A’aru.

Through his journey from life to death and to life again, Osiris was now seen to be connected to the earth’s cycles, such as the flooding of the Nile and annual harvests. Additionally, he was also heavily associated with fertility and the preservation of life through one’s descendants. Finally, the triumph of Osiris and his son, Horus, reflected the eternal struggle between chaos and Ma’at.

Judgement of the Heart

Once the deceased had recited the 42 Negative Confessions, it was time for the judgment of Osiris. Thoth is usually depicted as a scribe standing alongside Ma’at next to the golden scales. Osiris would take the heart of the deceased and place it on the scales against Ma’at’s feather, the symbol of cosmic balance and justice.

If the heart weighed more it was cast aside for Ammit to eat and if the scale was balanced Osiris welcomed the individual to the eternal afterlife. Many were terrified of this part of the journey and the spell from the Egyptian Book of the Dead was supposed to address this and keep the heart from betraying them. Furthermore, this particular spell and even parts from this spell are often found engraved on items within tombs, most often scarab beetles. These were thought to provide additional protection.

In some versions of the myth, the judgment of Osiris was not the end of the soul’s dangerous journey. Whilst in many variations, the deceased walked to the bank of the Lily Lake or Lake of Flowers and was escorted across by the ferryman, in others, the divine ferryman named Hraf-Hef (which translates to “he who looks behind him”) posed another test. Hraf-Hef was troublesome and would try to get a rise out of the traveler. If the deceased replied to the ferryman’s irksome behavior in any way other than kindly, they failed the test and would not be allowed into the A’aru.

Overall, the Weighing of the Heart Ceremony embodies many ancient Egyptian beliefs about both life and death and the New Kingdom. It was important to live in harmony with Ma’at, and it was through this that a person could earn themselves a place in Egypt’s idyllic afterlife.