Largely overlooked in modern American society, the War of 1812 is often overshadowed by the United States’ initial struggle for independence and the American Civil War, two existential conflicts that define the country’s development. The War of 1812, however, is an important milestone that set the foundation for expansion in the North American continent, allowing the United States to develop politically, militarily, and economically. While the war’s outcomes are more transparent, its causes are a complex assembly of grievances that boiled over to a climax in 1812.

British Impressment

One of the primary catalysts of the War of 1812 was the widespread British impressment of American sailors. The British navy often coerced unsuspecting individuals into service in wartime, and manpower requirements during the Napoleonic Wars led the Royal Navy to forcibly recruit American sailors by claiming that they were deserters. While the US Navy had impressed sailors during the American Revolutionary War, the British Navy’s impressment of American sailors was a major provocation to the newly independent American people. All in all, approximately 10,000 American mariners were impressed during the Napoleonic Wars.

In 1794, the Washington administration dispatched John Jay to negotiate with the British, but the resulting Jay Treaty did not address impressment and caused an outcry. Thomas Jefferson and James Madison demanded a more assertive response to the British. As president, Jefferson passed the Embargo Act of 1807, prohibiting American ships from trading in British and French ports. Although the policy was designed to enforce American neutrality and compel the British to stop impressing American seamen, the law was repealed two years later after causing significant economic damage.

Despite the downsides of impressment, sailors who escaped the practice, including future United States naval officers Charles Stewart and John Digby, often acquired advanced knowledge of British tactics and techniques, which informed the United States’ war effort.

Trade Restrictions

At sea, British trade restrictions against the United States exacerbated hostile impressment. In 1807, England passed the Orders in Council, a sequence of decrees designed to limit global trade with France in response to Napoleon’s Continental Blockade of Britain. The legislation applied to foreign neutral ships, including the United States, by compelling international vessels to stop at British ports before exchanging goods with other European nations.

The Orders in Council significantly interrupted American markets. American ships sailing across the Atlantic were routinely found in violation, resulting in the seizure of American goods deemed contraband. President Jefferson’s Embargo Act of 1807 quickly proved more harmful to the United States than its European targets. Following the repeal of the embargo, Congress passed the 1809 Non-Intercourse Act, which enabled trade with European countries other than Britain and France. After finding the new bill difficult to enforce overseas, Macon’s Bill No. 2 reinstated trade with Britain and France under conditional terms.

Napoleon saw the latest American policy as a means to force the United States to reinstate its embargo with Britain by agreeing to stop intercepting American shipping. As Napoleon anticipated, this exacerbated tensions between the United States and Britain. The embargoes and trade restrictions were highly damaging to US economic interests, and American leaders began considering military action to defend their interests.

British Support for Native American Tribes

In the early 19th century, few alliances were as logical as that between Britain and prominent Native American tribes in the United States. Partnering with Native American groups following defeat in the American Revolutionary War gave the British an opportunity to resist American expansion without direct military involvement. For Native Americans, agreeing to alliances with Britain was a necessary means to protect their land against a mutual adversary. Prior to and during the War of 1812, Britain’s strategic alliances with Native American tribes spread from the then-Northwest United States to the Great Lakes region, encompassing Tecumseh’s Confederacy. Tecumseh and his brother, the Prophet, offered a powerful impediment to American expansion.

Early American leaders believed that victory over Britain gave the United States an inherent right to expand westwards without interference. By 1811, before the United States officially declared war on Britain, tensions between American settlers and Native Americans resulted in violent clashes. At the Battle of Tippecanoe, Governor William Henry Harrison of the Indiana Territory led American forces to inflict a crushing defeat upon Tenskwatawa’s forces. Two years later, Tecumseh was killed in the 1813 Battle of Thames, resulting in the collapse of the Native American confederation.

Territorial Disputes

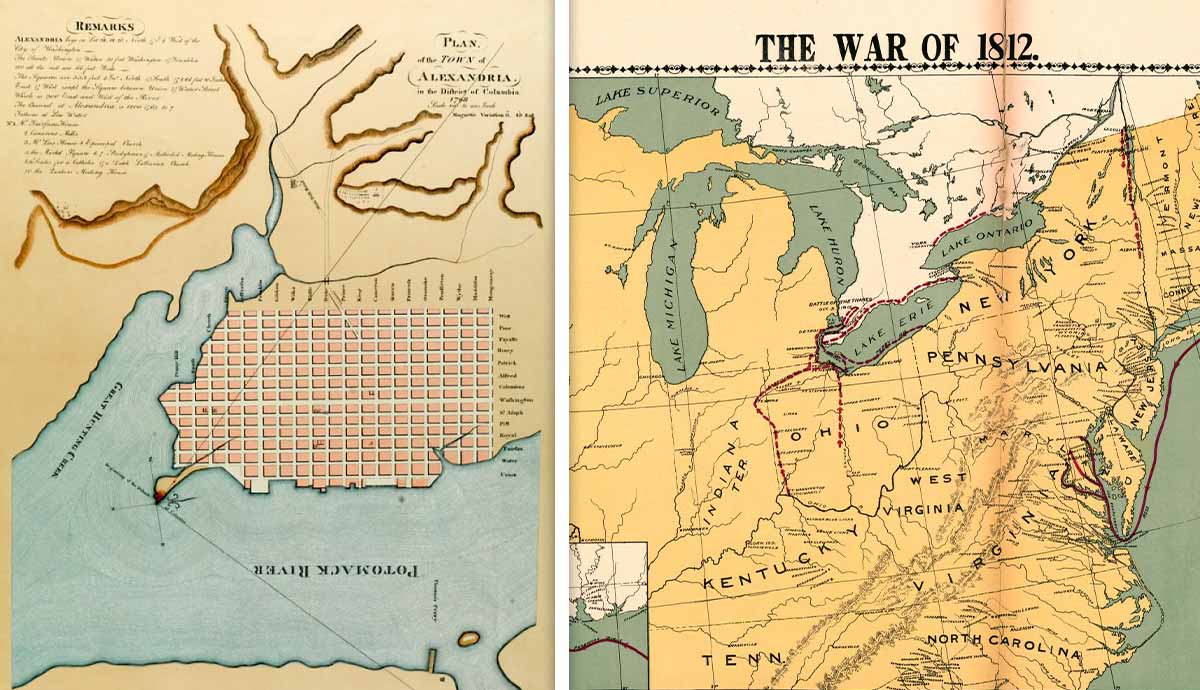

Following the American Revolutionary War, Article 7 of the Treaty of Paris specifically stated that the British military was to evacuate its forces from all forts and territories in the newly independent United States “with all convenient speed.” Despite this provision, the British retained key defenses in the Northwest Territory near modern-day Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin, Indiana, and Illinois. The British used Fort Detroit as a hub for operations with their Native American allies well after the Treaty of Paris mandated their departure.

Britain’s refusal to abandon its wartime fortifications extended into control of key American waterways. British-manned Fort Mackinac and Fort Niagara allowed them to exploit strategic positions near the Straits of Mackinac (which connects Lake Huron and Lake Michigan) and the Niagara River (which feeds into the Great Lakes). By continuing to garrison these outposts, the British not only ignored the terms of the Treaty of Paris outright, but continued to enforce prewar policies in the Northwestern territories.

Before the Revolution, King Geroge III published the Proclamation of 1763 to preserve the Appalachian Mountains for Native Americans, banning colonists from settling there. While the law became a dead letter after the founding of the United States, its lasting effects in the region complicated the United States’ expansion west. While American expansion remains controversial today, the continued British occupation of the Northwestern forts was a clear violation of the Treaty of Paris.

American Expansionism

Although the concept of Manifest Destiny, the inevitable and divine right of the United States to spread democracy throughout the North American continent, was not coined until 1845, American expansionism had an immediate foothold in the United States following the American Revolutionary War. Belligerent American politicians known as war hawks believed that America’s northern and southern frontiers could only be secured by armed conflict. By annexing British-held Canada and the Spanish territory of Florida, the United States could be free of foreign influence east of the Appalachian Mountains.

This plan, however, was not without strong resistance. Through Native American proxies, England aimed to create a deliberate buffer zone between the United States and British subjects in Canada. While the British strategy was intended to protect Canada, the War of 1812 began with a three-pronged American invasion of Canada.

To the west, British influence presented additional roadblocks to American ambitions of unopposed expansion. Less than a decade prior to the War of 1812, the Louisiana Purchase from France nearly doubled the physical size of the United States by adding 828,000 square miles of territory, including over a dozen current states. Under President Jefferson, the Louisiana Purchase and subsequent Lewis and Clark Expedition encouraged Americans to venture west for economic opportunity via new agricultural pastures and trade routes. This expansionism was met with British-supported Native American resistance, further escalating tensions prior to the outbreak of war.

National Honor and Post-Revolution Tensions

While events like Shay’s Rebellion in 1786 illustrate how the United States navigated domestic instability following independence, anti-British sentiment defined post-Revolutionary society in America. After eight years of fighting British forces with limited resources, the postwar United States was left in a fragile economic state. Popular rhetoric justifiably blamed the British for the economic damage during the war.

Alongside British-aided Native American resistance to expansionism, impressment, and territorial disputes, widespread anti-British sentiment following the American Revolutionary War fueled an era where a new America desired not only a country free of foreign influence, but also broader international recognition of American independence. Existing diplomatic approaches such as the Jay Treaty failed to address the main American complaints about British actions, fueling calls for war in the early 19th century.

The War of 1812 provided a means to gain national honor on the international stage. By defeating the British navy in several engagements, the United States gained increased overseas attention for its military prowess. Impending war also provided early American citizens with a sense of unity and identity that strengthened American nationalism following the conflict.

The War of 1812 was caused by several related factors that together encouraged American leadership to go to war with Britain despite the risks. Although the war was fought on a far smaller scale compared to the Napoleonic Wars in Europe, it was nevertheless a formative experience in the early American republic and came to be regarded as a second war of independence.