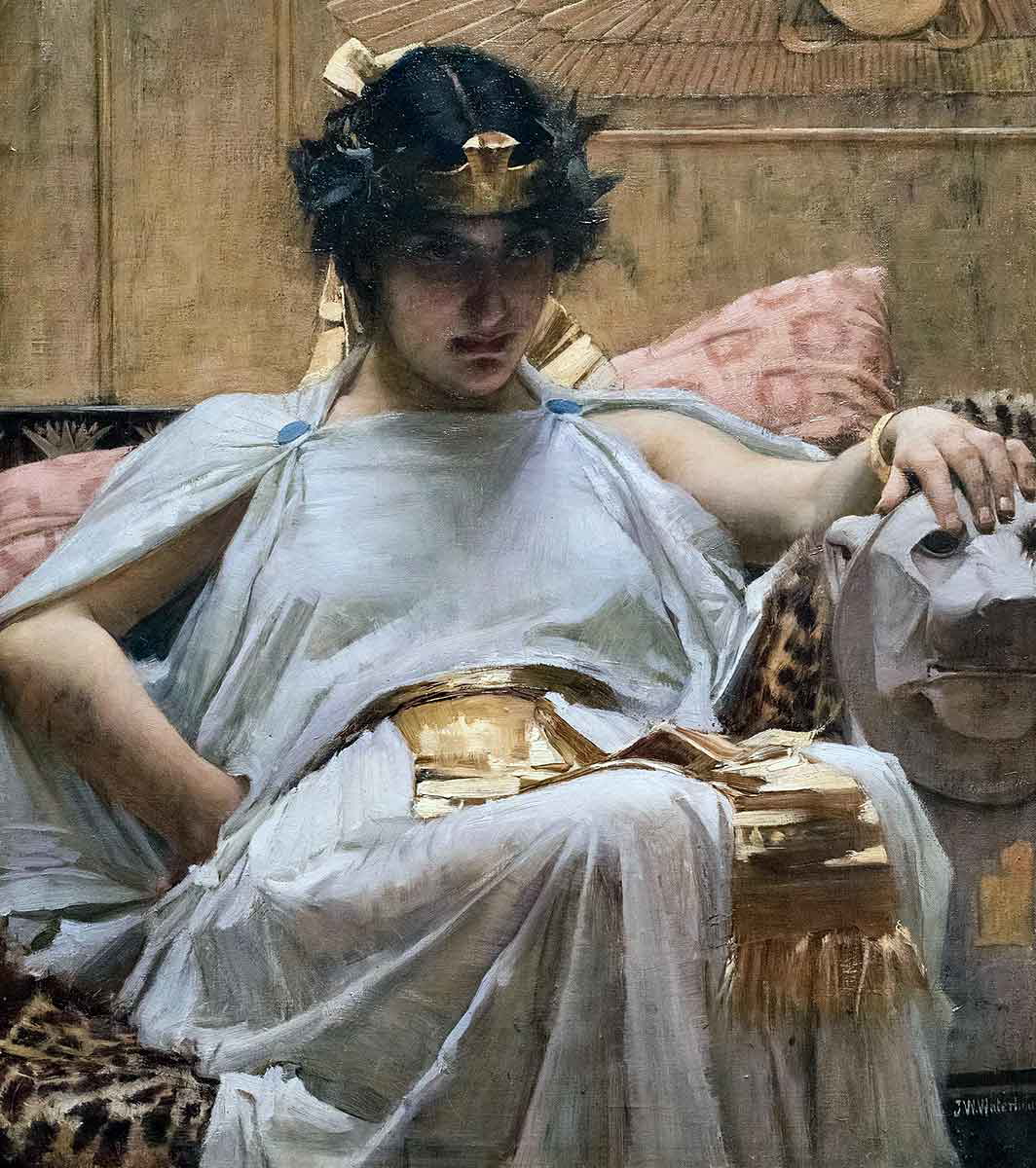

One of history’s most slandered yet enduringly captivating queens, the clever and charismatic Cleopatra isn’t often celebrated for her role as a mother. Frankly, that’s a disservice to her memory. Cleopatra wasn’t just a political powerhouse—she was also the fiercely protective parent of four potential game-changers, each raised with her sharp wit and strategic mind. Add to that her role as stepmother to another, and you’ve got a family saga worthy of an epic. Here are the stories of Ptolemy XV Caesar (Caesarion), Alexander Helios, Cleopatra Selene II, and Ptolemy Philadelphus—children with the makings of legends in their own right.

A Romance With Caesar and the Life of Caesarion

Cleopatra and Julius Caesar didn’t fall into each other’s arms at some languid feast under the stars—their love story began with political brinksmanship amid a civil war. This was where Cleopatra was reborn a queen who refused to lose. The nearly deposed female pharaoh famously engineered her introduction to Caesar by having herself smuggled into his quarters rolled up in a rug (or, if you prefer, a linen sack—equally dramatic). This wasn’t a flirtation—it was survival. She actually was in the city in secret, knowing her life was in danger. Her brother-husband, Ptolemy XIII, had pushed her out of power, and Cleopatra was determined to reclaim her throne. Enter Caesar, whose troops had Alexandria under their heels. Together, they turned the city’s war-torn chaos into Cleopatra’s victory, solidifying her rule and sealing an alliance that was as steamy as it was strategic.

The partnership wasn’t just about survival—it was about ensuring stability. Caesar and Cleopatra sailed the Nile in a lavish, gilded barge, projecting power as they went. It was a calculated PR move: Cleopatra presented herself as the reincarnation of Isis, goddess of kingship and motherhood, while Caesar basked in the glow of Egyptian divinity, proving that Cleopatra had not just the gods on her side but Roman muscle as well. Their connection transcended borders, combining Rome’s swagger with Egypt’s mystique.

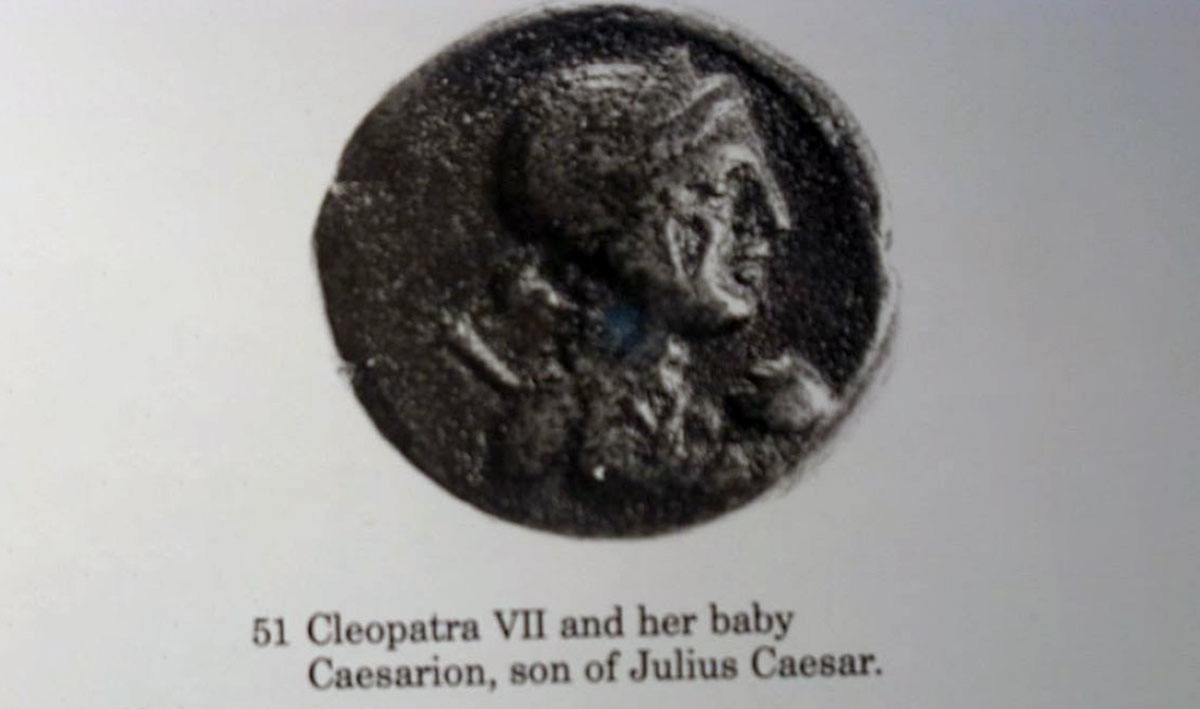

The fruit of their union was Ptolemy XV Caesar, better known as Caesarion, or “Little Caesar.” Cleopatra wasted no time in presenting her son as Caesar’s rightful heir, a move that sparked an inferno of gossip and outrage in Rome, where Caesar’s legal wife (Calpurnia) resided. Caesar did not shy away from the claim either. When Cleopatra and Caesarion visited Rome, they didn’t exactly slink in quietly—they stayed at one of Caesar’s properties, and he made no secret that the boy bore his name.

For the Roman elite, already uneasy about Caesar’s consolidation of power, this was the final straw. A foreign queen claiming her child was deeply connected to Rome? Unthinkable. In addition, it may have been during this visit that Caesar had a bust of Cleopatra dedicated at the temple of Venus…talk about an out-and-loud Valentine to his lover.

Of course, the smear campaigns practically wrote themselves. Cleopatra was painted as a scheming seductress, Caesar as an old fool bewitched by her “exotic” charms. But, little did the Roman population know Cleopatra was nobody’s fool. She was building a legacy, positioning Caesarion as a bridge between Egypt and Rome. If Rome would not recognize her son’s legitimacy willingly, Cleopatra had no problem reminding them who had the bloodline of pharaohs—and a baby with Caesar whether they liked it or not.

A Second Union: Three Children Beloved of Egypt

Cleopatra was no stranger to using alliances to secure power, but her relationship with Mark Antony following Caesar’s death was more than a shrewd political maneuver. It was the second act of her dynastic master plan and one that brought into the world three more heirs: Alexander Helios, his twin sister Cleopatra Selene, and little brother Ptolemy Philadelphus. These children weren’t just symbols of an influential union—they were Cleopatra’s insurance policy for Egypt’s sovereignty and a challenge to Rome’s dominance.

Antony, who already had Roman children, did not hesitate to double down on Cleopatra’s vision of dynastic rule. Not only did he proclaim Caesarion as Julius Caesar’s rightful heir, much to the irritation of Octavian, but he also brought his own son, Marcus Antonius Antyllus, to Egypt. Antony set up Antyllus and Caesarion as a two-man team: an Egyptian pharaoh and a Roman citizen, both born to inherit staggering power and smart enough to someday use it. While Caesarion represented the legacy of Egypt and Julius Caesar, Antyllus carried the weight of both the Antonian line and the patrician and dignified Fulvian line. Together, they were a calculated bet on a future where Rome and Egypt ruled side by side.

Antony did not stop there. At the infamous Donations of Alexandria, he handed out titles with grand theatricality. Caesarion was named “King of Kings” and hailed as the legitimate ruler of Egypt, while Alexander Helios, Cleopatra Selene, and Ptolemy Philadelphus were crowned rulers of their own swathes of Eastern territory. Cleopatra herself was styled as the “Queen of Kings,” cementing her children as the foundation of a dynastic empire that could rival Rome.

Octavian, one part of the uncomfortable alliance known as the Second Triumvirate with Antony and Lepidus, was not having it. He spun the relationship of Antony and Cleopatra into a melodrama of foreign corruption, painting Cleopatra as the ultimate femme fatale and Antony as a man without proper Roman pride and laziness. When Octavian’s forces crushed them at the Battle of Actium, the dream of an Alexandrian empire came crashing down. Rather than endure the humiliation of a Roman triumph—effectively a death march masquerading as public entertainment—Antony and Cleopatra chose to die on their own terms. Their suicides were acts of defiance, denying Octavian the spectacle he craved. The twosome’s children, however, were not so fortunate.

As for Antony and Cleopatra, their tomb has yet to be discovered—a final act of rebellion, a middle finger to Octavian’s efforts to control their story. Somewhere, beneath Egyptian sands or lost to the sea, they rest together, their love and ambitions forever mystifying those who wanted to make them fallible and human. Cleopatra may have lost the war, but in death, she remains one of history’s most enduring enigmas.

Male Heirs No More

History is written by the victors, and Octavian, later Augustus, was nothing if not thorough in wiping away threats to his rule—especially those with bloodlines that could rival his. The fate of Cleopatra’s sons, heirs to both Egyptian and Roman legacies, is a tragic testimony to the ruthlessness of political survival in the ancient world and Octavian’s driving motivation to consolidate power.

Of all the male heirs, Ptolemy XV Caesarion, son of Julius Caesar and Cleopatra, posed the gravest threat to Octavian’s ambitions. Cleopatra had sent Caesarion to safety in India under the care of his Greek tutor, a desperate ploy to preserve the boy’s life. Whether the tutor’s betrayal or sheer miscalculation sealed the young pharaoh’s fate is unclear but Plutarch tells us that Caesarion was lured back to Alexandria and executed on Octavian’s orders. Some whispers from antiquity suggest that Caesarion may have evaded capture, but there is no evidence to support this hope. What we know is that the boy who bore the name of Caesar was inconveniently alive—and Octavian had no intention of sharing power with anyone who could stir Roman hearts by invoking Ceasar’s memory.

Caesarion was not the only male heir erased from history. Antony’s son Marcus Antonius Antyllus, brought to Egypt to train alongside Caesarion as part of a planned Egyptian-Roman alliance, met a similarly brutal end. After Antony’s defeat at Actium, Antyllus sought sanctuary at a shrine. It didn’t matter: the boy was dragged out and summarily executed, his jewels purloined by the very tutor who was meant to protect him.

1586-1628. Source: Raw Pixel

The fates of Cleopatra and Antony’s younger sons, Alexander Helios and Ptolemy Philadelphus, remain hazy at best. We know Alexander, crowned as King of Armenia at the Donations of Alexandria, was displayed in Octavian’s triumphal march in golden chains alongside his twin sister, Cleopatra Selene. Yet, he disappears from the historical record shortly after, never mentioned as having reached adulthood. Ptolemy Philadelphus, the youngest, doesn’t even make it that far; he isn’t recorded as being part of the triumph at all, suggesting he may have died even earlier, a quiet casualty of Octavian’s systematic purge.

Why Octavian may have targeted the boys isn’t hard to surmise. These children embodied Cleopatra’s vision of a united dynasty that could rival Rome. They carried the blood of two of the ancient world’s most powerful families, and they were, quite literally, born to rule. Octavian, ever the pragmatist, knew he could not allow them to grow into men who might challenge his authority. Whether they were executed outright, poisoned, or left to perish in the shadows of captivity, their deaths served Octavian’s agenda of erasing all competition. We will probably never know for certain how these boys met their ends. We simply see them disappear from the historical record.

While the exact details of their fates may be lost, the intent is unmistakable. Octavian was not just dismantling Cleopatra’s dynasty—he was scrubbing it from genetic memory, leaving only fragments of their stories for history to piece together.

But the Moon Rose

While the male heirs of Cleopatra faded into the shadows of history, Cleopatra Selene—daughter of the infamous queen and Mark Antony—rose to forge her own legacy. Unlike her brothers, she doesn’t quietly vanish from contemporary sources. Octavian understood the power of Cleopatra’s daughter not just as a political pawn, but as a symbol. So, instead of erasing her, he married her off in grand fashion, gifting her a hefty dowry and sending her to North Africa to rule alongside Juba II, newly minted king of Mauretania.

Juba and Selene were, by all accounts, an extraordinary power couple. Both carried the scars of Rome’s imperial expansion: Juba had been paraded in Caesar’s triumph as a child after his father’s defeat and subsequent suicide (sound familiar?), and Selene had been displayed in Octavian’s own triumph alongside her brothers. Perhaps this shared trauma drew them together, or perhaps they simply recognized one another as equals. Whatever the reason, together they turned Mauretania into a cultural beacon in the ancient world.

Under their reign, Mauretania became a fusion of Egyptian, Greek, and Roman influence. They built a dazzling metropolis at Caesarea (modern-day Cherchell, Algeria), blending architectural styles and scholarly traditions from the three great cultures. Temples with Greek columns stood alongside Egyptian motifs, and Roman efficiency underscored the city’s infrastructure. Coins minted during their rule showed Juba and Selene, one on each side, presenting them as a united front, a king and queen not just of a territory, but of a shared vision.

The pair also had at least two children, a son, and a daughter, though their fates are somewhat unclear. Cleopatra Selene’s legacy didn’t stop there—centuries later, Zenobia, queen of Palmyra and a fierce rival to Rome, claimed descent from Selene and Juba. Whether or not this claim of inheritance was true, speaks volumes about the enduring power of Selene’s story.

For all the grandeur of their reign, Selene and Juba’s lives were undoubtedly shaped by the traumas of their youth. Both had been torn from their homes and made political pawns, but together, they turned those tragedies into precursors to triumphs. Cleopatra Selene might have been taken from Egypt, but in Mauretania, she created a kingdom that reflected her mother’s vision of uniting the best of the ancient world. In a way, Selene did not just rise above her circumstances—she rose to the status of a queen who honored her lineage while forging her own path.