The Chicano Moratorium called attention to serious issues, but it was intended to be peaceful. Thousands of marchers converged in Los Angeles in 1970. Their aim was to protest the disproportionate number of Chicanos being drafted and killed in Vietnam, but they also celebrated Chicano culture and history. However, a dubious “crime” led to an outsized police response, and a day that began with excitement and togetherness ended with a total routing of the marchers, many injuries, and the death of beloved Latino journalist Ruben Salazar.

Who are Chicanos?

Chicanos are Mexican-Americans born in the United States, who primarily live(d) in California, Texas, New Mexico, Nevada, and Colorado. There are several hypotheses about the origins of the term, but it was certainly initially used derisively by Mexicans south of the border for those who lived on the opposite side, which, by the 1920s, had become a considerable number of people, when migration from impoverished Mexican cities to California skyrocketed. The term suggested those Mexicans were now less Mexican because they were scrabbling for an existence along the border of the two countries.

In the 1960s and 1970s the term was co-opted by activists, artists, and community organizers in El Movimiento to distance themselves from the hyphenated term “Mexican-American” as well as the colonizer-inflected term “Spanish.” Chicanos celebrated their heritage, fought against discrimination, and tried to inculcate “Chicano pride” and “Brown pride” among their people.

Actor and activist Cheech Marin wrote in an article entitled “What is a Chicano?” that to him, “you have to declare yourself a Chicano in order to be a Chicano. That makes a Chicano a Mexican-American with a defiant political attitude that centers on his or her right to self-definition. I’m a Chicano because I say I am.” UNIDOS, an organization that helped fund Marin’s Center for Chicano Art & Culture, explains that the word is more than just a term: “it’s a declaration of cultural identity, rooted in a complex history of colonization, migration, and activism. From its etymological origins to its role in the Chicano Movement and beyond, the term has served as a powerful symbol of unity, empowerment, and pride for Mexican Americans. Understanding the origins and evolution of ‘Chicano’ offers invaluable insights into the struggles and triumphs of a community continually shaping its identity and place within the American tapestry.”

Chicano Life in Southern California in the 1960s

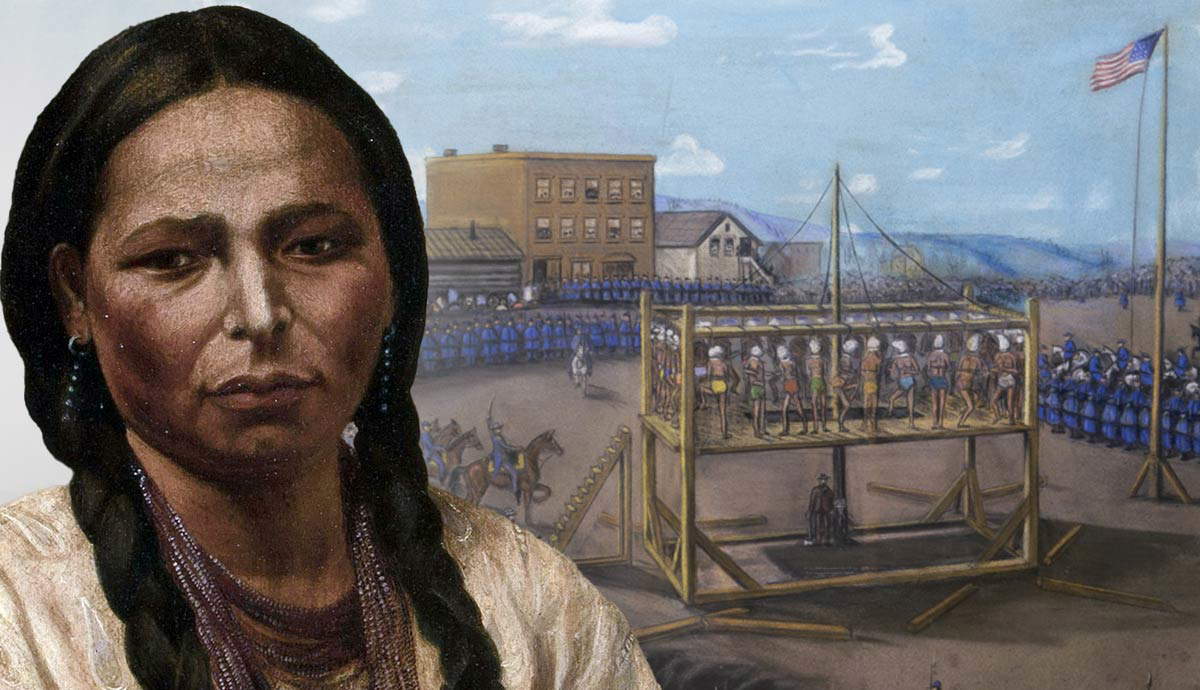

Chicanos had been in the Southwestern United States for a long time. The end of the Mexican-American War in 1848 resulted in the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, which brought current-day California, New Mexico, Utah, and Nevada into the United States. Mexicans living in those territories were now uneasily American, though not awarded citizenship. Over time, more people migrated from Mexico, especially during the first decades of the 20th century. Like African Americans in the South, they experienced racial discrimination and segregation. In 1947, Mendez v. Westminster struck down segregation between white and Mexican schools (a case which became an important precedent for Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas in 1954, which struck down all school segregation). In 1954’s case Hernandez v. Texas, the Court ruled that the 14th amendment gave Mexican Americans and all other nationality groups equal protection under the law.

Despite increasing constitutional protection, many Chicanos in the Southwest experienced poverty, poor education, continued racial discrimination, and unsafe working conditions (especially in migrant farm work, in which they made up a disproportionate number of laborers).

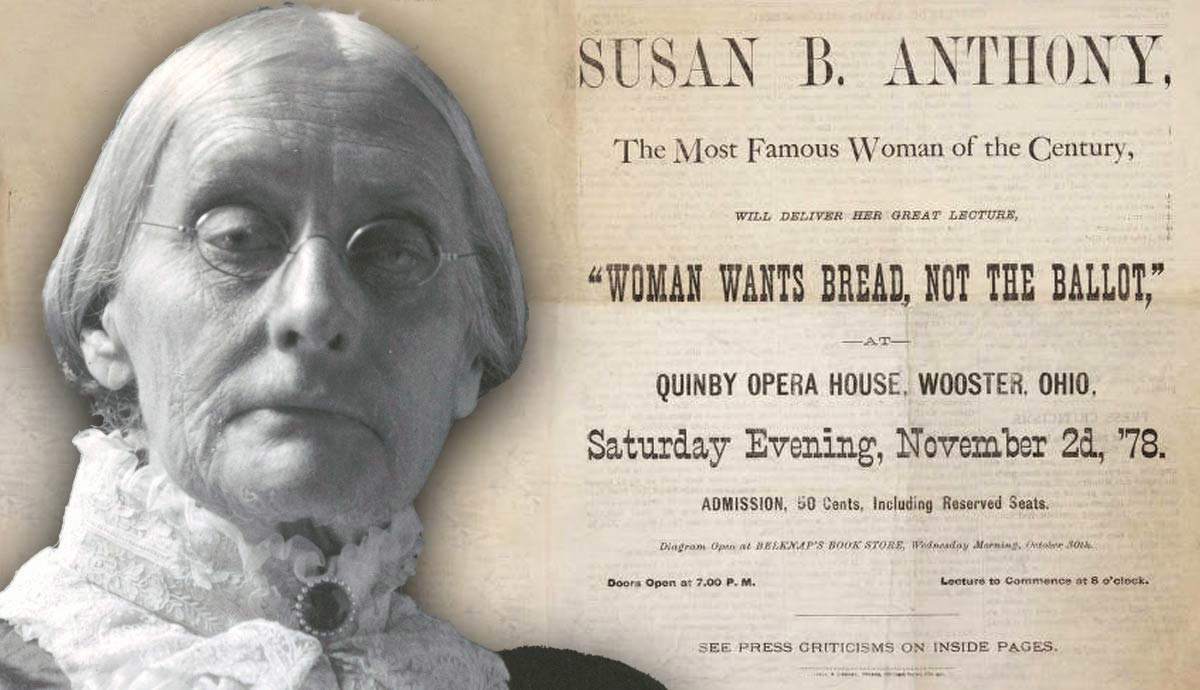

As the civil rights movement swept the Black community in the 1950s and 1960s, Chicanos in the Southwest began to organize around issues that directly affected them. Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta founded the National Farm Workers’ Association, which became the United Farm Workers, in order to call for better working, social, and economic conditions for migrant workers in central California agriculture. In his 1969 “Letter from Delano,” Chavez stated that “We are men and women who have suffered and endured much and not only because of our abject poverty but because we have been kept poor. The color of our skins, the languages of our cultural and native origins, the lack of formal education, the exclusion from the democratic process, the numbers of our slain in recent wars—all these burdens generation after generation have sought to demoralize us, we are not agricultural implements or rented slaves, we are men.”

The Vietnam War

American involvement in the Vietnam War officially began in 1965 when Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, giving President Lyndon Johnson carte blanche to send American ground troops to South Vietnam and accelerate aerial bombing of Communist North Vietnam. Though Johnson had declared in 1964 that “we are not about to send American boys 9 or 10,000 miles away from home to do what Asian boys ought to be doing for themselves,” it became necessary by 1965 to raise the draft numbers in order to meet the needs of the war. Johnson’s argument was now that North Vietnam and Communist China wanted to “conquer the South, to defeat American power, and to extend the Asiatic dominion of communism. . . . An Asia so threatened by Communist domination would certainly imperil the security of the United States itself.”

Between 1964 and 1973, 2.2 million American men out of an eligible pool of 27 million were drafted. As being enrolled in college allowed for a deferment, those drafted tended to be disproportionately from the lower classes and from communities of color. People with Spanish surnames were dying twice as much as people without in proportion to their population in the region. Artist and scholar Harry Gamboa Jr. summed up the anger thusly: “People are trying to persuade you that you are less than human, and at the same time need your human body to go fight a war and make sure you never get an education.” Carmen Ramirez, now a politician and an activist, remembered thinking, “We were looking at the numbers of casualties and how they were distributed among people of color—you know Latinos are always the most gung-ho about going to war—and they were coming back dead, or terribly wounded…So what are we doing there?”

The Walkouts

On March 5, 1968, hundreds of Chicano students—which eventually became 22,000 as the week progressed—at the Eastside high schools of Garfield, Roosevelt, and Lincoln walked out of their classrooms just after noon, chanting slogans such as “Viva la revolucion,” “Education, not eradication,“ “We demand schools that teach,” and “We are not ‘dirty’ Mexicans.” These initial walkouts, or “blowouts,” helped pave the way for the Moratorium.

These students were frustrated by many aspects of their educational experience. The schools were rundown, many of the teachers were openly racist, and the students were more and more demoralized. Dropout rates were high; many Chicano students felt like they weren’t even expected to graduate.

For a week the walkouts continued and the students, helped by the Brown Berets, listed their demands. The district only agreed to two: more bilingual staff and smaller classes. Later, it helped law enforcement round up 13 activists whom a grand jury later indicted for conspiracy. Despite the ignominious end to the blowouts, they brought together many of the people who would organize and participate in the Moratorium two years later.

The Moratorium: From Planning to Action

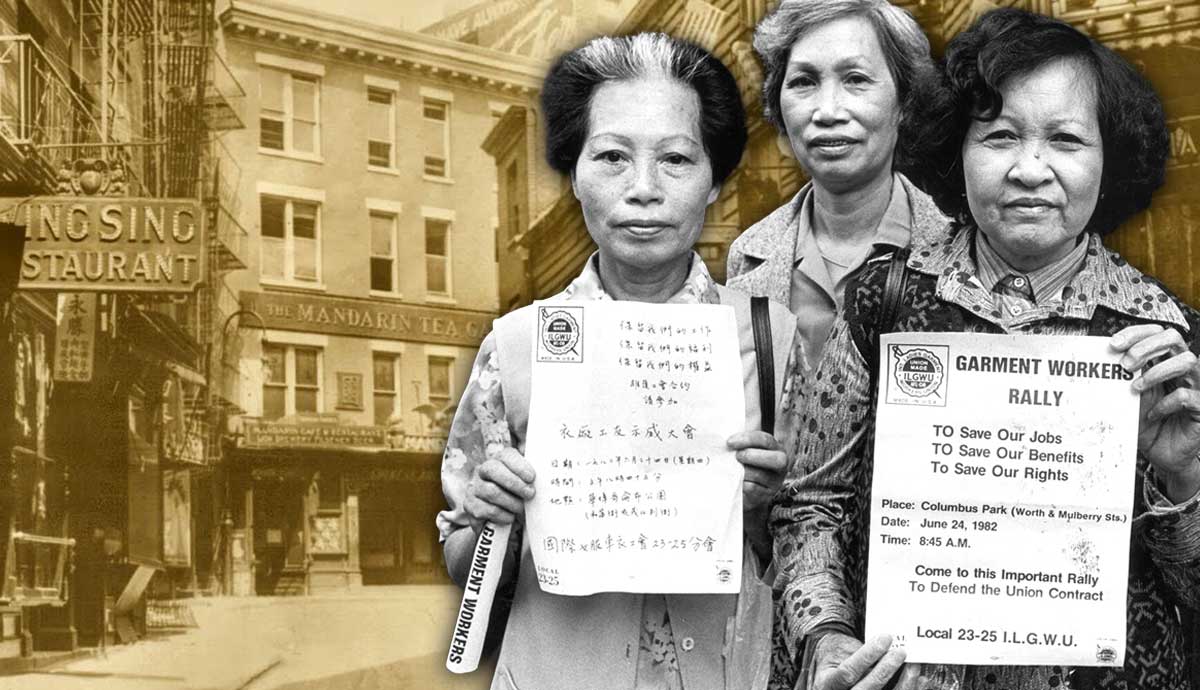

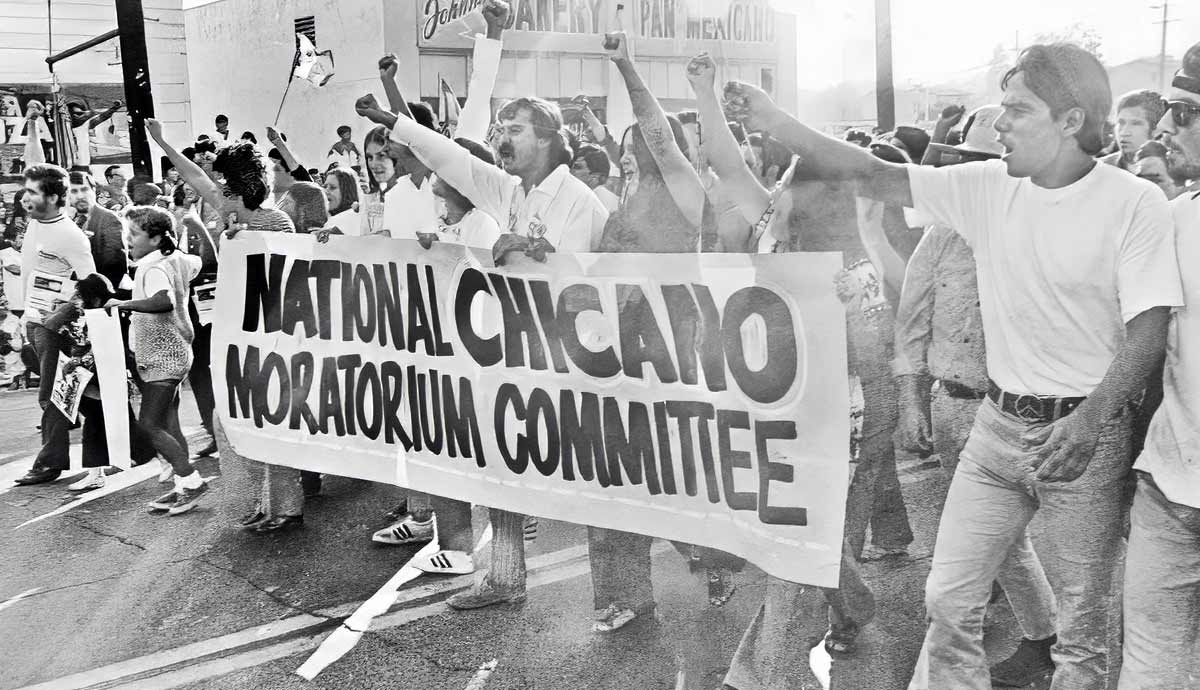

The Moratorium event was planned by the National Chicano Moratorium Committee, which consisted of members from several radical groups, including the Brown Berets, the Crusade for Justice from Colorado, the Communist Party, Las Adelitas de Aztlán, and the Black Berets from New Mexico.

The goal wasn’t just to bring attention to what was going on in Vietnam but also to connect that injustice to events at home. For example, one of the popular slogans was “Our War is not in Vietnam, it is in our Barrios.” Bill Gallegos noted in an article for The Nation commemorating the event that it “highlighted the ironic reality that Chicano troops in Vietnam had among the highest casualty rate among US forces, while suffering double-digit drop out/push out rates in the schools and high rates of mass incarceration, and minimal access to higher education.”

August 29, 1970 was a bright, warm day in Los Angeles. Over twenty thousand people gathered for the parade on Whittier Boulevard. There were, of course, Chicanos, but also Native Americans, African Americans, Puerto Ricans, Asian-Pacific Islanders, and white people. Old and young, artists and professors, factory workers and teenagers all gathered for what looked to be a jubilant and powerful day of marching, celebrating Chicano culture, and showing what a united community with a keen political consciousness looked like.

As the parade made its way to Laguna Park for a picnic and speakers, a few protesters stopped into a liquor store to buy drinks. The shopkeeper assumed that they were robbing him and called the police. Eventually over 500 sheriff’s deputies, deeming the gathering unlawful, confronted the participants with batons and tear gas, in some cases routing and pursuing them into nearby streets. The disturbance lasted five hours, resulted in three dead, 200 arrested, 95 county vehicles destroyed, 44 buildings pillaged, and eight fires set. An article about the event describes the scene: “A 3-square-mile area—bounded roughly by the Pomona Freeway on the north and Olympic Boulevard on the south—was the scene of people running for cover and riot-equipped police in gold-colored helmets and gas masks advancing in military formations, trampling spectators and clubbing those who did not move fast enough.” Unsurprisingly, “for many in the community, it confirmed their complaints of abusive and indifferent law enforcement.”

One of the three killed was Ruben Salazar. Salazar was an award-winning Los Angeles Times columnist, the beloved “voice” of the Chicano community. He had ducked into the Silver Dollar restaurant after covering the parade and the riot, and was drinking a beer when a tear gas projectile burst into the restaurant and hit Salazar’s head, killing him instantly. The police claimed that it had been a tragic mistake, that they had gotten a tip that a man with a gun had entered the restaurant. Some people in the community believed that the FBI had targeted Salazar by using the chaos of the Moratorium to assassinate this voice of dissent. Whether it was an accident or not, it was a tragic capstone to an already tragic day, and a death that reverberated in the community for decades to come.

The Moratorium: A Complicated Legacy

The tragic events of the day did not mean that Chicanos gave up protesting unfair conditions. They continued to call attention to the unfair representation of Chicanos drafted into and dying in the Vietnam War, to police brutality, and to general discrimination in American society. Carolina Miranda, a Los Angeles Times arts writer, noted the effect the Moratorium had on arts and scholarship: “The Moratorium shifted creative paths for those who were present and those who heard about it on the news or from friends. It fueled an urgency to make visible the Chicano experience, one that had largely been left out of the history books—an urgency that remains resonant at this time, when the Latino cultural presence in the U.S. remains evanescent, and when protesters around the world have taken to the streets in uprisings against police brutality.”

In 2011, the Sheriff’s Department did issue a report stating that deputies had used excessive force that day and were poorly trained to handle crowds of that size. But it was a long time coming, with decades in between in which discrimination and distrust persisted. In the Los Angeles Times, Eduardo Aguirre, an ex-convict who heads a local addiction recovery program, noted that “the violence did bring all our problems out into the open. But was it worth nearly destroying our community to do it?” Mario T. Garcia, a professor, said “Organizing the massive demonstration of Mexican Americans’ opposition to the Vietnam War was a huge achievement for the Chicano movement. But it turned into a riot, which had the ironic effect of tagging the movement as violent even though deputies had caused most of the trouble. The Chicano movement never fully recovered.”