The Protestant Reformation is the term historians use to describe the changes that occurred within European Christianity in the 16th and 17th centuries. However, this period was characterized by convulsive changes in many areas of European society, not only its religions. Placing the Reformation within the context of these changes can aid reflection on its ongoing effects on religion and culture. Its effects on art are especially clear.

Pressure From the East and Shifting Populations

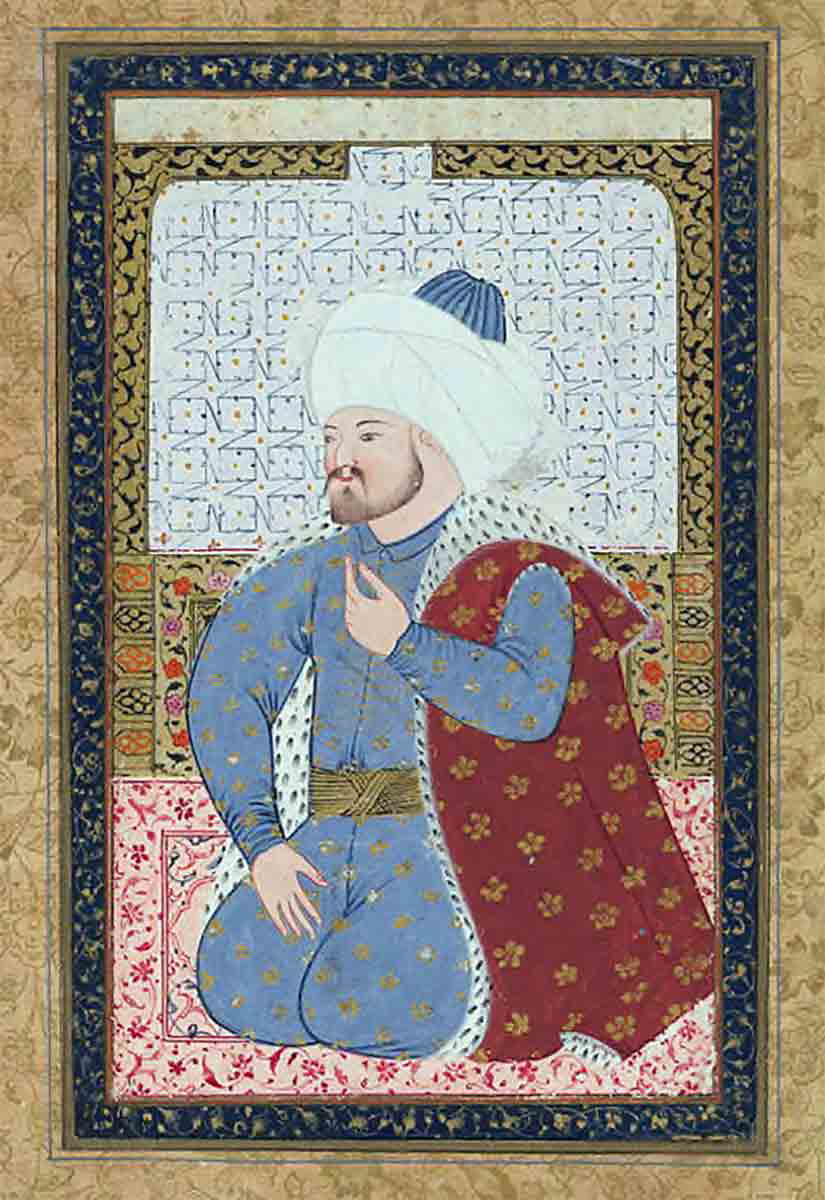

The Ottoman conqueror Sultan Fatih Mehmet II’s conquest of Constantinople in 1453 was the climax of several hundred years of Ottoman incursions into formerly Christian lands in southern Europe, some of which had changed hands between Muslim and Christian rule several times in previous centuries. But Constantinople had unparalleled symbolic and strategic significance, and its fall was troubling to European Christian identity.

Meanwhile, after centuries of struggle, Christian monarchs had finally driven the last Muslim ruler from the Iberian Peninsula (modern Spain and Portugal). This occurred in 1492, only a year prior to the fall of Constantinople. By 1500, both the Jewish and Muslim inhabitants of this area had been forced by decree from the Holy Roman Emperor to convert to Christianity or leave (the Jews had already been expelled from France and England two centuries earlier). Many of these Jews and Muslims found themselves settling in communities in Ottoman-ruled areas, and many in the city that had once been the center of the Byzantine Empire, but that was now newly named Istanbul.

Thus, in a formal sense, Europe was becoming less religiously diverse. In retrospect, this is ironic, since Europe was about to give birth to one of the most religiously variegated movements in its history: the Reformation.

The Reformation would introduce new religious identities in even more localized regions than Muslim and Christian identities had done. Whole areas of Europe would become “Protestant,” and wars would be fought between Catholic and Protestant armies. Meanwhile, those persuaded by the doctrines of either the Catholics or the Protestants or those groups who, like the Anabaptists, found fault in both, would find themselves pushed and pulled by persecution in different directions across Europe and beyond. These additional movements would further serve to drive people of similar identities toward each other.

Rome’s Declining Political Influence

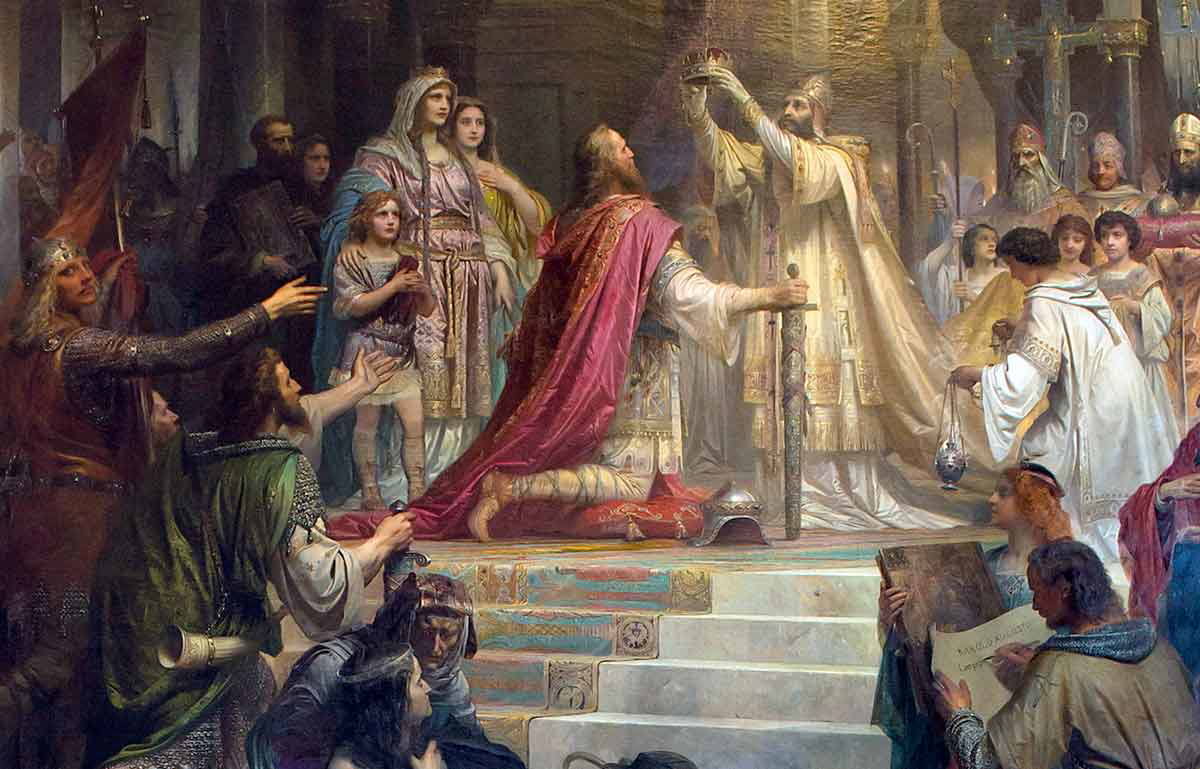

Politically, the center of the Roman Empire had already shifted to central Europe by the 16th century—that is, away from Rome. A precedent had been set when Pope Leo III crowned the Frankish king Charlemagne the first Holy Roman Emperor in the year 800. This occurred during a time when the empire’s eastern side, centered in Constantinople, was beginning to separate from the West, centered in Rome. However, in crowning a Frank, Pope Leo III (perhaps unwittingly) was shifting the center of European power northward from Rome.

By the 16th century, fewer and fewer emperors were making the trip to Rome to be crowned, and their role as emperor had become increasingly symbolic. The emperor was elected by noblemen spanning from Italy to the Netherlands; military prowess was not a necessary condition for the position. These “holy” emperors wielded a fraction of the power that ancient Roman emperors had enjoyed, and they lived in the shadow of Charlemagne. By the time of the Reformation, thus, the “Roman” nature of the empire was already a matter of history. This left the Roman Catholic Church as the only thread left tying Rome to the center of European identity. Meanwhile, the Byzantine side of Christendom had succumbed to the Islamic Ottoman Empire.

The decline of Roman political influence cannot account entirely for the religious shift that would later take place in the Reformation. However, this background helps to explain why the Reformation was able to break vast sections of Europe from the Roman Catholic Church so swiftly.

Trade Was Pulling Wealth Toward Northwestern Europe

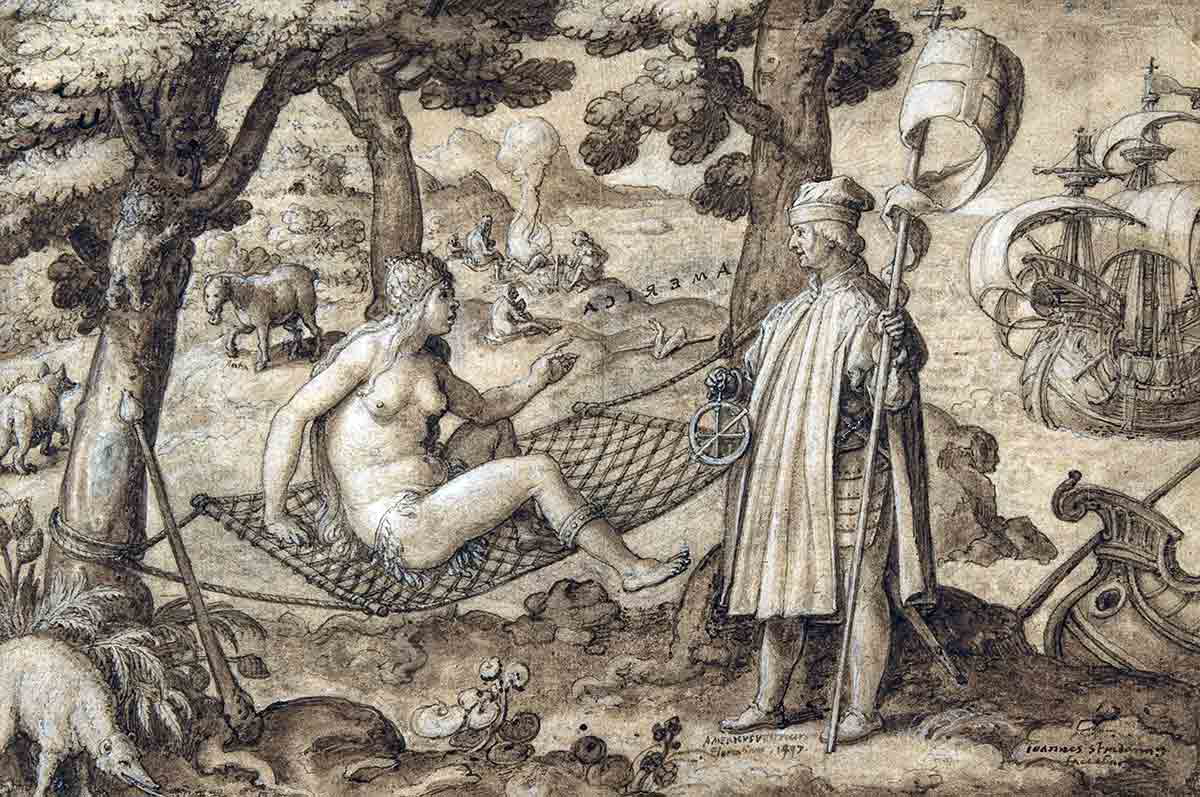

The 16th century was also an age of exploration. Advances in navigation science and technology, as well as improvements in ship design, were facilitating exploration and trade across an expanding radius from Europe. Europe’s arrival in the Americas was one of the most significant developments of this period related to trade.

As European monarchs sponsored these explorations, their dependence upon trade with Asia diminished. Sea travel was much faster and more efficient than land travel necessary for bringing goods from the East. Furthermore, the “new world” was across the Atlantic Ocean, not the Mediterranean Sea. Thus, the pull of Atlantic trade in Europe constituted another force that encouraged a more localized focus, spreading the centers of Europe’s trade economy from the south and east to the north and western shores of the continent. As new economic and social arrangements dominated by trade and technology and driven by competition emerged, the precursors of capitalism were being set in place.

While discussions of capitalism often focus on its effects on social and economic class, its relationship to geography is also important. As monarchs seized opportunities to bring wealth into their realms through exploration and trade, the stage was being set for parallel religious changes. Rome was distant, Mediterranean, and in the south. The benefits of a tie with its Holy See were fading for central and northern Europeans in the 16th century. A more localized religion that surrendered less authority to a far-away pope served their ends much better. The “new” brand of Christianity the reformers preached was, thus, attractive to some central and northern European princes and lords for political and economic reasons as well as for its religious persuasiveness.

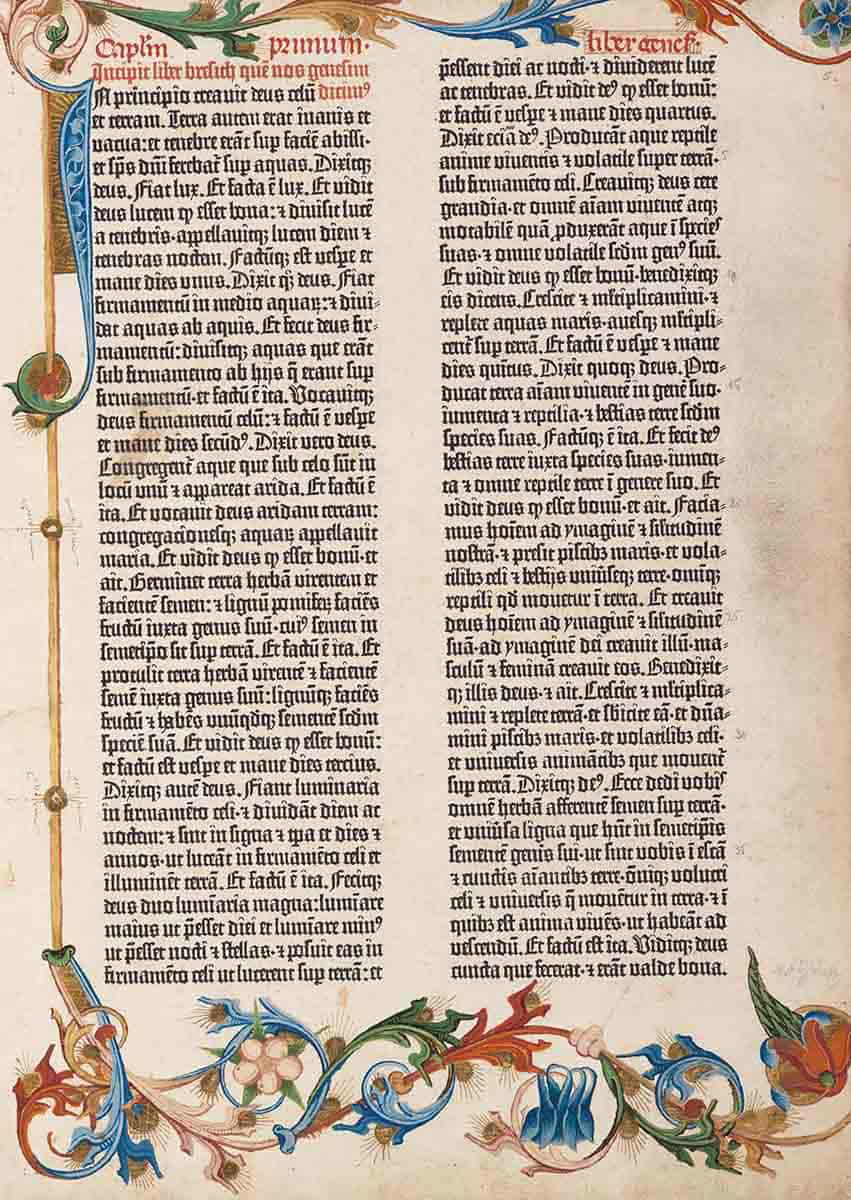

Printing Press Technology and the Bible’s Availability

A crucial technological development of the period leading up to the Reformation—one of the most influential inventions in world history—was Gutenberg’s printing press. While printing technology had been used in Europe since Roman times, a German goldsmith in the city of Mainz named Johannes Gutenberg invented a press around 1440 that used moveable type—that is, the letters and other figures could be rearranged in any order instead of the printer-maker’s having to create new etchings for every page.

Gutenberg’s invention increased the accessibility of books in Europe exponentially, both because of the rapidity with which books could now be printed and also the steep decrease in the labor costs that went into creating them. This new technology made disseminating information and ideas much easier than had previously been possible, and this further began to erode the exclusive hold that church officials had on religious ideas and information.

Gutenberg’s invention is perhaps the clearest example of how technological changes in Europe intersected with emerging religious changes, for the Bible was the first complete book that Gutenberg printed. Though printed in Latin, Gutenberg’s Bible created the possibility and demand for the Bible’s availability in contemporary European languages. The availability of the Bible was a key part of what opened the door to interpretations of its teachings that differed from those established by the Roman Catholic Church.

The Reformation Was (Still) Primarily a Religious Movement

While it is possible and fascinating to identify a plethora of factors that set the stage for the Protestant Reformation, it was nothing if not religious in character. Perhaps the strongest evidence for this claim is the personal risk that was taken by its central characters.

It is common to identify the 14th-century theology professors Jan Hus (Bohemian/Czech) and John Wycliffe (English) as forerunners of the Reformation. Like the reformers, they believed that the Bible should be available in commonly spoken languages. But Hus was burned at the stake for his teachings, and Wycliffe’s doctrines were likewise condemned—his remains were unburied so that they could be burned to symbolize his fate as a heretic.

If Hus can be imagined as Martin Luther’s predecessor, it is easy to imagine him meeting a similar fate. Luther’s teachings were condemned as heresy in 1521. But instead of being executed, he was excommunicated from the church and condemned as an outlaw, which meant that anyone could kill him with impunity. It was only due to the covert action of the German prince Frederick III of Saxony that Luther was able to escape death. Frederick literally captured Luther under the cover of darkness and hid him in a castle at Wartburg, where Luther continued writing in secret.

While Frederick did not publicly adhere to Luther’s ideas, he was willing to defy both the church and the Holy Roman Emperor for the sake of asserting control over his local realm and to defend one of his subjects whose popularity was growing.

Other key figures of the European Reformation, such as John Calvin, Ulrich Zwingli, and Philip Melanchthon, likewise enjoyed the sponsorship of local princes and kings. Thus, even though the Reformation was certainly religious at its core, it could not have happened without the accompanying changes that were happening in European society as a whole.

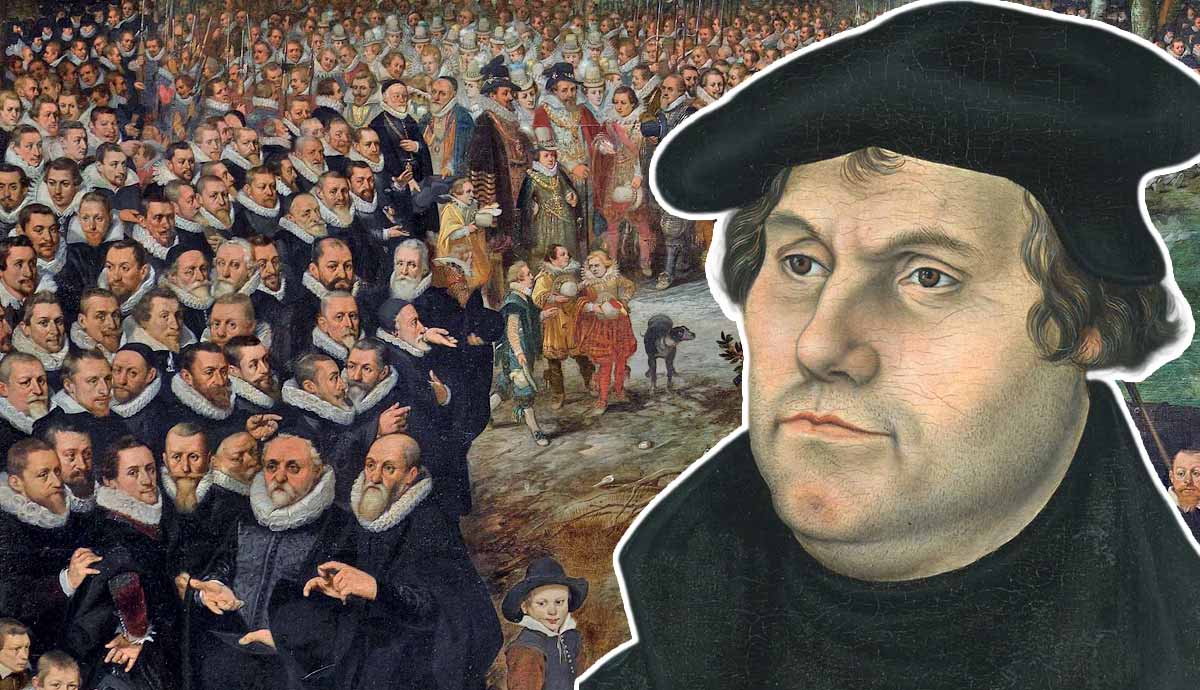

Martin Luther’s Place in the Reformation

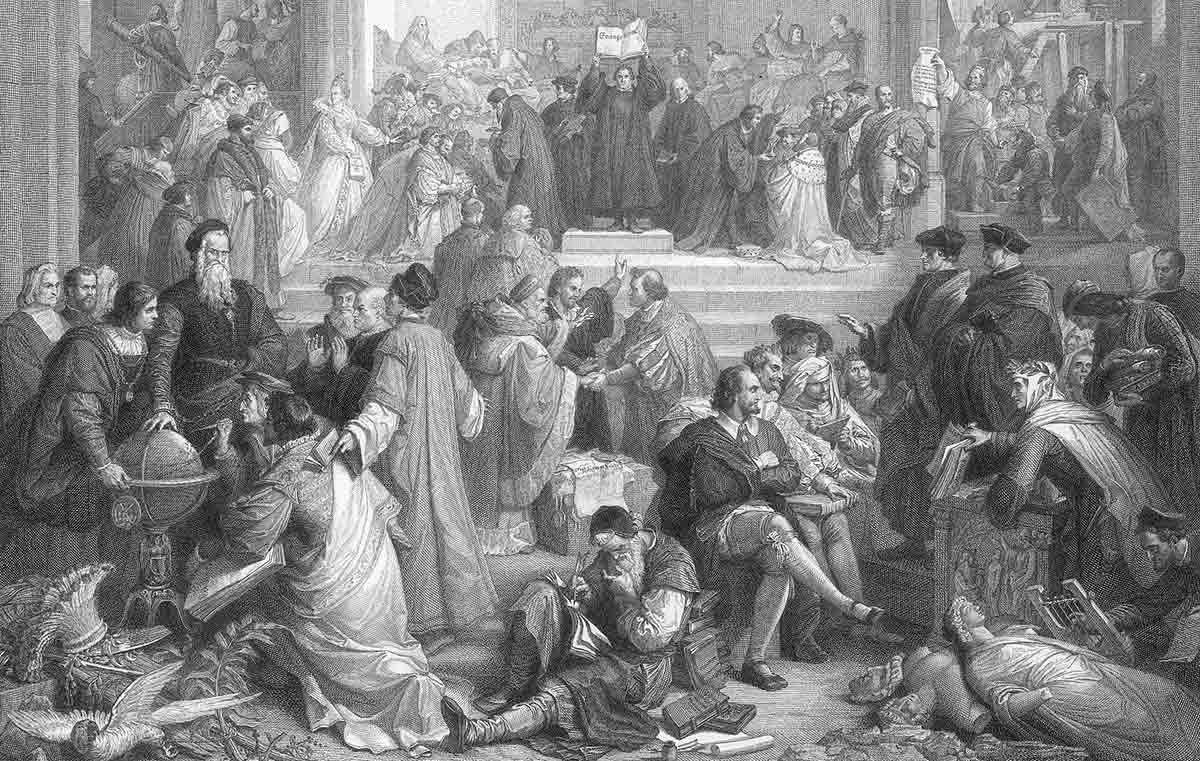

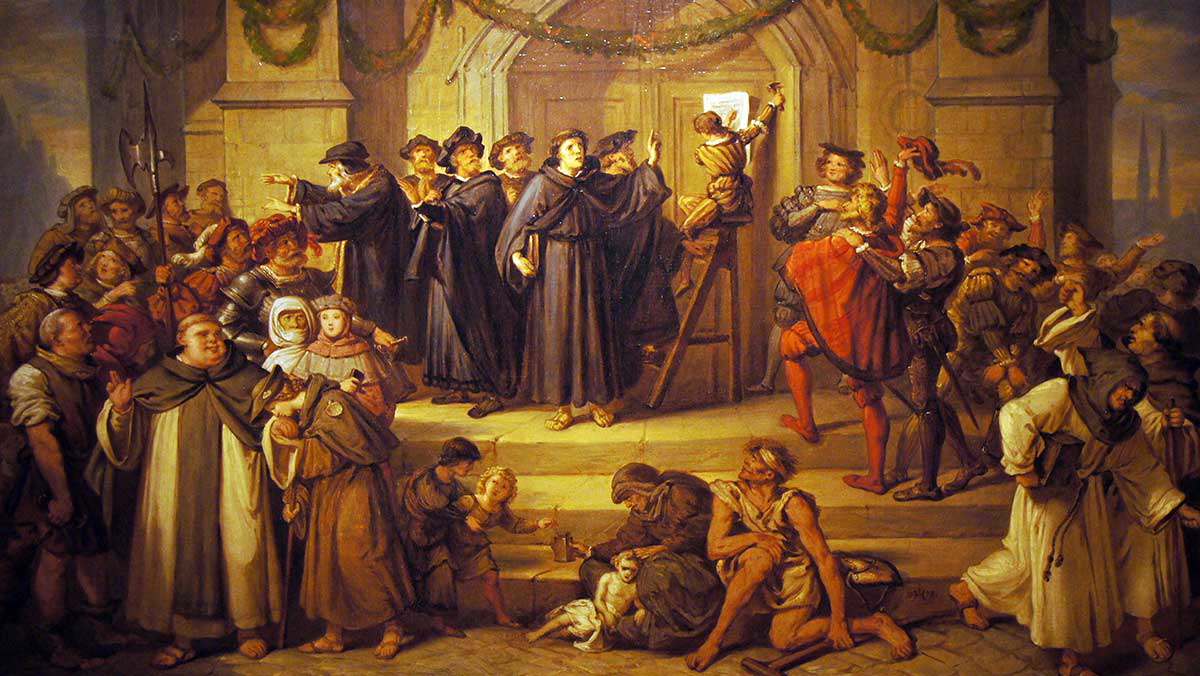

The ninety-five theses that Martin Luther nailed to the door of the chapel at Wittenberg on October 31, 1517, addressed an issue of church practice that is almost never discussed in Christianity today: the sale of “indulgences”—remission of postmortem punishments in Purgatory in exchange for donations to the Church. Luther found this practice to be without theological grounding. Actually, the Roman Catholic Church would later acknowledge that indulgences had been abused at the Council of Trent.

Luther’s criticisms in these ninety-five theses were not extreme, and it is unlikely that he would have realized the storm that they would provoke in Europe. For this reason, historians are often interested in examining the mix of factors that caused Luther’s relatively modest action to become the catalyst for the far-reaching changes that they did.

Since Luther never intended to leave the church, it is important to keep his title as “reformer” in mind; his initial goal was to spur debate and change, not to divide the church. His protests later became increasingly radical, however, until he was finally expelled from the church as a heretic in 1521 at the Diet of Worms. After his expulsion, any restraints that church tradition could have placed on his theology were lost. As his support among the German nobility increased, his rhetoric against the Pope and the institutions and teachings of the Roman Catholic Church also increased.

While Luther’s concerns were primarily about religious matters, his message had political implications. Protestant movements became increasingly connected to nationalist movements in Europe as both Protestant groups and the European nobility saw less and less of a need to be connected with Rome. Thus, Luther’s theology unintentionally contributed, at least to a limited extent, to the emergence of the idea of “nation-states”—nations defined by ethnic identities within certain geographical boundaries.

Art Before the Reformation

The biblical command against making “carved” or “graven” images, which has often troubled Christian artists, became a lightning rod issue in the Reformation. However, the Reformation was not the first period in Christian history in which art was at the forefront of a controversy. The 8th and 9th centuries both saw “iconoclastic” movements develop—efforts to forbid or restrict the use of images in worship. Importantly, these debates centered on Constantinople, not Rome. While these movements ultimately failed and while the Church across medieval Christendom affirmed the use of images in worship, the Eastern Church has tended to oppose the use of three-dimensional statues due to their association with idolatry.

The West, however, had no equivalent movement in opposition to statues or icons before the 16th century. Roman Catholic Christendom had long produced extravagant artworks in abundance, including many statues of saints and biblical figures. The West’s liberal approach to art may have set the stage for the reaction that occurred during the Reformation. Reformers saw themselves as returning to Christianity’s roots in biblical teaching. The command against images was, for many of them, clear enough. Thus, like the “iconoclasts” of centuries past in the eastern church, some reformers called for art in churches to be destroyed.

Reformation, Iconoclasm, and Its Legacy

Reformation zeal against images was directed specifically toward those images that people would be tempted to worship or address in prayer. While there was a range of opinions about images among reformers, iconoclasts—literally, “image-breakers”—earned their name mostly in churches. Several waves of iconoclasm racked churches in Europe as the Reformation’s burgeoning influence took a stronger and stronger hold on European hearts and minds. Religious art took a significant turn during this period, with many artists being forced to flee to Catholic areas of Europe even as their masterpieces were being destroyed.

The cloud of opposition to religious art had a silver lining, however. Young artists who might otherwise have been restricted to depicting religious themes in their work took up other subjects instead. Some historians credit the Reformation with facilitating the birth of “secular” art for this reason. A new era of art depicting landscapes, still life, and historical subjects was born during this period.

Some of the reformers, most notably Martin Luther himself, were not opposed to religious art. Thus, Protestant religions that had adopted Lutheran theology (parts of Germany and Scandinavia) continued to produce religious art. England, which saw its own distinctive version of a Protestant Reformation later than Europe did, likewise continued to produce art for use in worship, religious teaching, and devotion.

Meanwhile, as European economic vibrancy was shifting north and west due to developments in trade, a “golden age” of art was born. Particularly in the Netherlands, where artists like Rembrandt (Protestant) and Vermeer (Protestant convert to Catholicism) worked, Protestant areas proved their ability to produce great art even though their focus had been redirected. Protestant iconoclasm did not seek to suppress art per se, but art that was perceived as idolatrous. Thus, even as the walls of Protestant churches were laid bare, Protestant artists found other places to display their work.

The Reformation’s Complicated Legacy

Separating out which aspects of the Reformation were strictly religious in nature from the many other seismic social, economic, philosophical, and technological changes that were happening in Europe when it appeared is difficult. Ultimately, historians prefer to examine the Reformation’s effects and causes from a variety of interrelating perspectives. Exploration into the many ways in which the Reformation affected not only the religious, but also the cultural, aesthetic, political, and other aspects of life in Europe continues, as historians approach the subject from new angles.