Throughout the Medieval Period, there were nine major crusades, with most aspiring to reclaim the holy city of Jerusalem from Muslim control. While some saw minor, short-lived successes, the majority resulted in humiliating defeats for the Christians and reaffirmed the power and strength of Muslim forces in the East. With the Ninth Crusade concluding in 1272 CE due to King Edward I of England’s return home to claim his crown, the impact and legacy of the Crusades can still be seen across both East and West almost 800 years later.

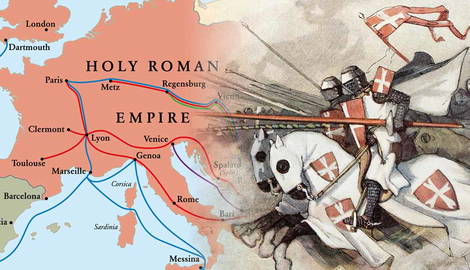

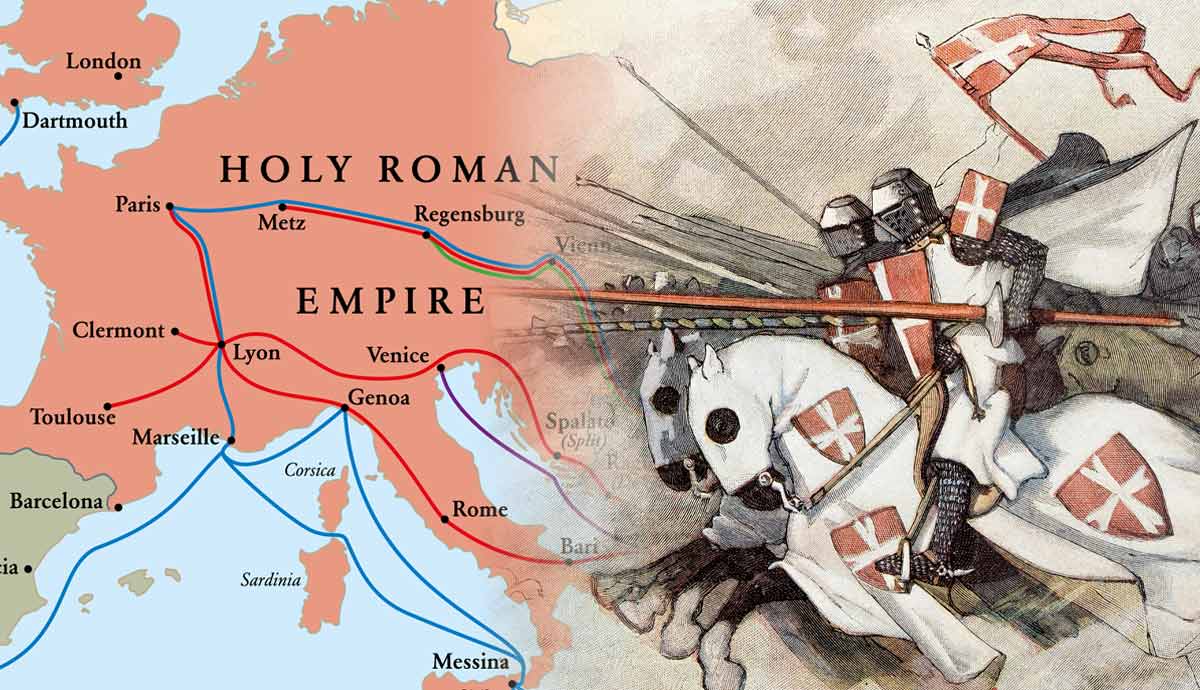

The First, Second, and Third Crusades, 1096–1192

A cry for help from Emperor Alexios I of the Byzantine Empire against the Seljuk Turks saw Pope Urban II launch the First Crusade, sparking a series of holy wars that lasted almost 200 years. Men across Christendom embarked east in search of adventure, wealth, and spiritual salvation. The Crusaders’ mission to help Alexios reclaim Byzantine land was a mere “stop on the road” as the Christians pushed on to their true goal of capturing Jerusalem. The Muslims, disorganized with no leadership, were unable to hold off Christian advances. By 1099, the Crusaders had won, and Jerusalem now came under Christian control.

The Muslim counterattack was swift, and with the unification of Muslim forces under one leader, Imad al-Din Zengi, the Crusaders were forced to launch the Second Crusade in defense of the Holy City. A succession of powerful Islamic leaders in Nur al-Din and Saladin saw Muslim forces sweep through the Holy Lands, with each victory dealing devastating blows to Christian forces and their morale. With Saladin’s unification of his own lands in Egypt and Nur al-Din’s territories in Syria, Saladin’s forces overwhelmed his Christian enemies, and the city fell into Muslim control once more in 1187.

Christian kings across Europe vowed to reconquer Jerusalem. The Third Crusade was launched in 1189 with King Richard I of England, King Philip II of France, Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, and Guy de Lusignan uniting their forces to challenge Saladin’s hold over Jerusalem. However, constant quarrelling between the Christian leaders led to continuous military failure, and the Crusaders were unable to secure the Holy City. The Third Crusade ended in 1192 with Jerusalem still firmly under Saladin’s control. However, a truce between Saladin and Richard I allowed Christian pilgrims and merchants to pass freely through the holy city.

The Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Crusades, 1202–1229

Despite Christian failures, Pope Innocent III launched the Fourth Crusade in 1202. Jerusalem was, again, the main target; however, the Crusaders faced financial difficulties in Venice. Unable to pay the Venetians for a fleet to sail east, the Crusaders helped Alexios Angelos, the son of a deposed Byzantine emperor, to reclaim the Byzantine throne in return for payment. The Crusaders succeeded; however, Alexios was unable to pay. Alexios’s rule was soon usurped, leaving the Crusaders without their pay. In 1204, the Crusaders sacked Constantinople, desperate for financial gain. The aim of conquering Jerusalem was soon abandoned as many Crusaders were too exhausted physically, mentally, and financially to continue.

Innocent was determined to reclaim Jerusalem, but the Fifth Crusade’s goal was to conquer Egypt, securing it as a strong base for future attacks on Jerusalem. The Siege of Damietta in 1218 saw initial Crusader success; however, it came with high Christian casualties. Sultan al-Kamil of Egypt offered Jerusalem in exchange for a Crusader withdrawal from Egypt. Papal legate, Pelagius, however, rejected his offer and instead marched towards Cairo. The Crusading armies found themselves ensnared in the flooding of the Nile and surrounded by Egyptian forces. Innocent’s armies were forced to surrender, give up Damietta, and return home with the Crusade in tatters.

Pope Gregory IX looked to launch a Sixth Crusade with the support of the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick II. However, Frederick continually delayed the crusade’s launch, leading to Gregory excommunicating Frederick in 1227. Despite this, Frederick launched his own crusade, turning to diplomacy and negotiation with Sultan al-Kamil for success. The two agreed Jerusalem was to return to Christian control, with Temple Mount and Al-Aqsa Mosque remaining under Muslim control. The Treaty of Jaffa was to last ten years, with Frederick II named King of Jerusalem outside the Roman Church.

The Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth Crusades, 1248–1272

Frederick’s ten-year truce soon expired, and Jerusalem fell once again in 1244 to Egypt with the help of Muslim mercenaries. King Louis IX of France, after recovering from illness, vowed to launch the Seventh Crusade as thanks to God for his mercy. Egypt remained the Crusader target, and after successfully capturing Damietta, Louis turned his attention towards Cairo. The Christians faced further humiliating defeats en route at Al Mansurah and Fariskur, where Louis was captured and ransomed for the return of Damietta. The Seventh Crusade marked yet another defeat, costing France huge numbers of casualties and financial strain.

Despite his failures, Louis launched the Eighth Crusade. The conflict in Egypt had paved the way for the rise of the Mamluk Sultanate, which had now begun to target the Crusader states in the Holy Land. Louis, aged and his health deteriorating, was determined to keep fighting, and focused on Tunis, where he hoped an attack would force its ruler to convert to Christianity and gain an ally for his cause. However, disease swept through the Christian armies in the intense heat, leading to Louis’s death in August 1270. With their leader dead, the Crusader troops withdrew from North Africa.

One leader, however, continued towards the Holy Land, launching the Ninth Crusade. Prince Edward of England was determined to defend Crusader lands in the East, as the Mamluks now threatened the Christians’ remaining territories. Edward experienced some success, from allies with the Mongols who attacked Muslim forces in Syria, to Edward’s own small victories in the Holy Land against his enemies. However, in 1272, Edward’s father, the King of England, died, forcing Edward to return home to claim his position as King Edward I. Edward’s departure left the Crusader states almost defenseless, resulting in the final fall of Acre to the Mamluks in 1291.

Lessons From the Past

With the last major crusade concluding almost 800 years ago, it can be difficult to see their relevance in modern society. The passion and intensity with which participants fought to claim or defend the Holy Land demonstrates the spiritual gravitas the Crusades had within both Christianity and Islam.

Jerusalem was a city that was fought for, in some capacity, in all nine of the Crusades. The bloodshed during and since the Crusades is exemplary of the devastation and chaos that can ensue from a lack of tolerance and understanding of different faiths and cultures. Frederick II’s negotiations during the Sixth Crusade demonstrate the power of negotiation, and the cohabitation of Christian and Muslim peoples under the Treaty of Jaffa shows how differences can not only be put aside but celebrated together.

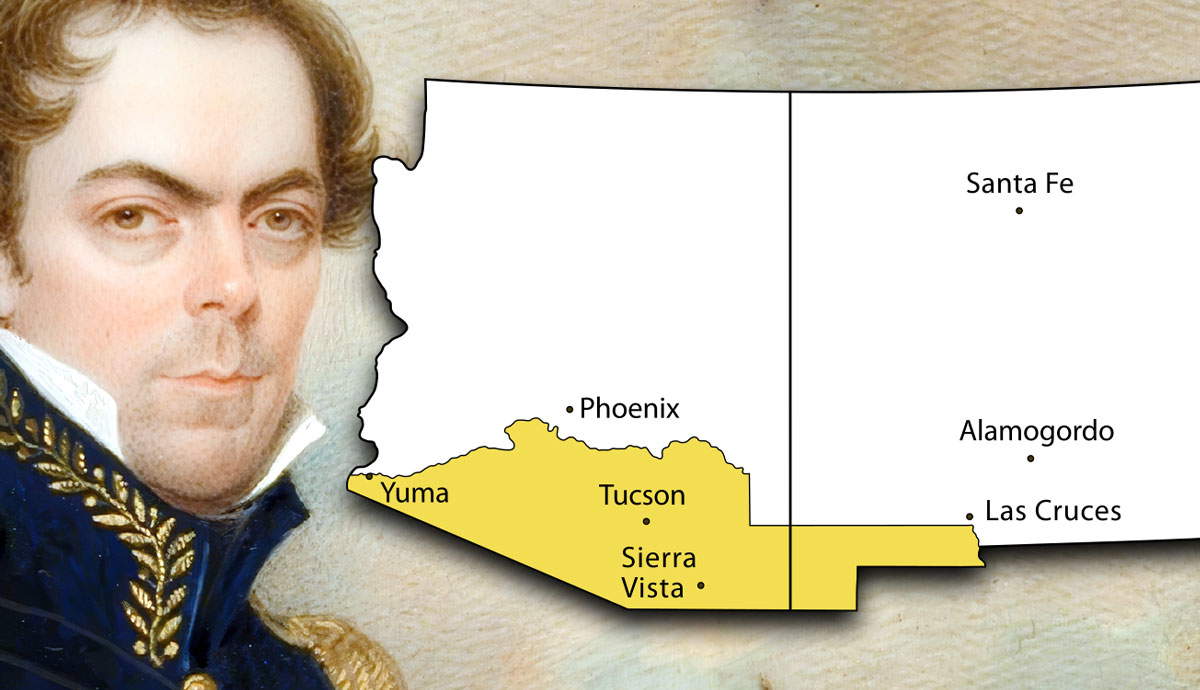

The Crusade ideology of “the other” has inspired many throughout history to use religion to justify expansion and conquest. The concept of holy war brought military action and religious belief together, laying the groundwork for later colonial and imperialistic tendencies. The British Empire is but one example of this, where belief in the superiority of the white, Christian world drove a desire to spread British control and “Christianize” colonies.

The Legacy of Crusading Leaders

Many of the Crusades’ leaders have been revered and remembered in history for their part played in the wars. Saladin, a hugely successful military strategist, is revered today as a great historical leader. His tactics and strategies have been studied by military commanders since, hoping to learn from his expertise.

Richard I is also remembered as one of the greatest British monarchs in history. Richard’s strategies and determination to stand alone after disagreements with his allies have overshadowed Richard’s own spending of English wealth on the Third Crusade, leading to King John’s unpopular, yet arguably necessary, decision to tax the English people to replenish his coffers.

Some legacies, however, remain more hidden than the characters that appear frequently in popular culture. The Knights Templar, a religious, military brotherhood founded to defend Christian pilgrims venturing to the Holy Land, have been credited with the creation of the modern banking system. Originally designed for travelers to keep possessions safe during their travels to Jerusalem for a small fee, the financial system we use today is immediately recognizable in the Templars’ early creation.