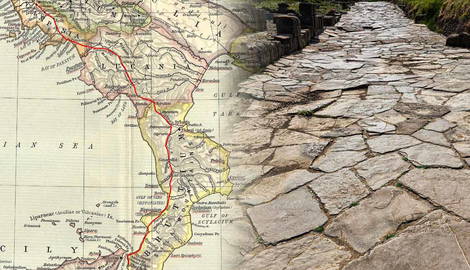

At the height of the Roman Empire, Roman roads, measuring a boggling 250,000 miles, crisscrossed the entire empire, moving goods, armies, or transmitting culture. Of this sum, paved roads accounted for 50,000 miles. While famous routes like the Via Appia c. 312 BCE receive the lion’s share of attention, four kinds of roads existed, each designed with a purpose.

Stitching the Empire Together

These consisted of via publicae (public highway), viae militares (military road), viae privatae (private roads), and viae vicinales (local roads). Built with the famous Roman tenacity, these roads typically fared straight as possible, despite obstacles like hills or valleys. Where feasible, Roman engineers constructed bridges or aqueducts to shorten travel time.

And with such precision, the roads meant Roman administration followed the empire. In newly conquered areas, roads became a physical and psychological presence.

Tools, Layers, and Durability

Building a road isn’t easy, but engineers took on the task with Roman practicality. Their tools first. Engineers (agrimensores in Latin) employed various methods to assess distances and confirm the straightest route. The tools utilized included a groma, chorobates, and dioptra. These tools assisted with measuring angles, height, and orientation. Roman roads still exist, carved from mountainsides. The Romans properly surveyed and planned their roads. With terrain as a factor and with a tendency for straight lines, the Romans yielded only as needed. Integration and ease of travel emerged as the top priorities.

The Romans built their roads to last. Whereas many ancient roads existed as dirt tracks, the Romans went all out, making theirs with four layers. The first layer, called the statumen, was put down after digging a trench using large foundational stones. A second layer called the rudus used mortared smaller stones for structure.

The nucleus (third layer) consisted of finer crushed stone upon which workers laid pavimentum (stone slabs). Engineers cambered the pavimentum for drainage, increasing the road’s lifespan. Lime mortar and volcanic stone (if available) became the favored materials, prized for their long-lasting qualities.

1. Viae Publica

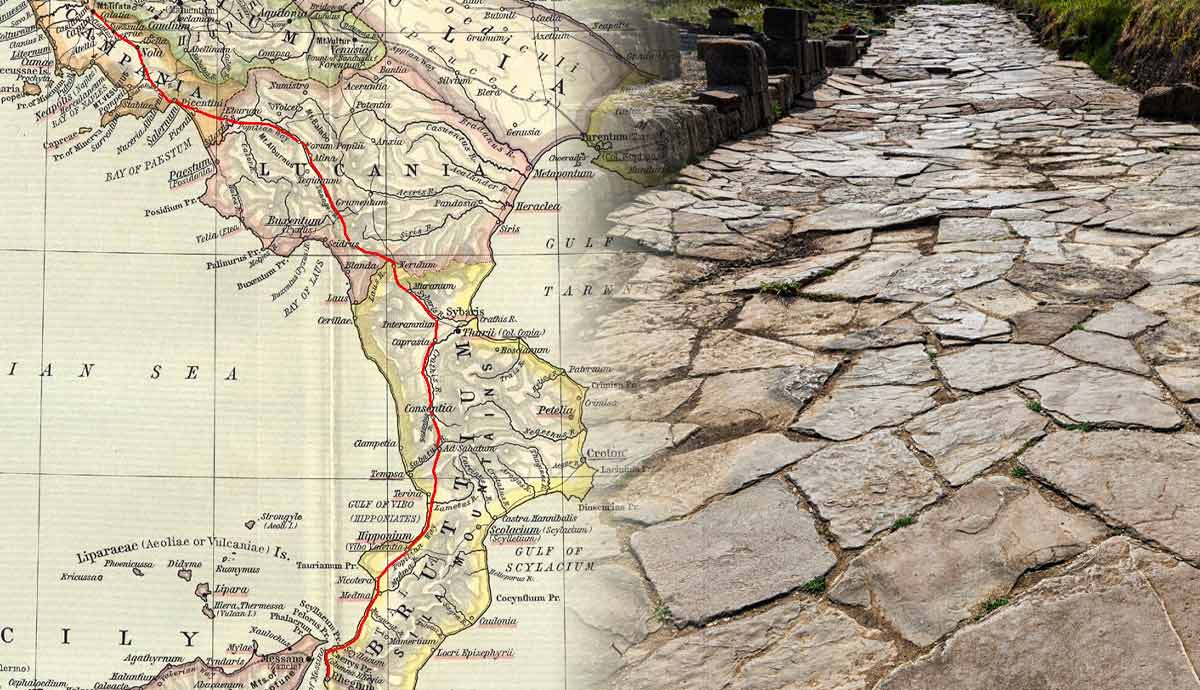

Perhaps the most photographed and well-known, the Viae Publica existed as state-funded roads. These roads spanned the Empire, as the Greek historian Dionysius stated that “paved roads helped the Roman Empire manifest greatness.”

As built for official use, the state maintained the Viae Publicae. Built from the best materials, these roads connected major cities, ports, and far-flung provinces. To aid navigation, the Imperial government built mile markers, rest stations (mansions), and patrols against bandits.

Famous preserved examples include the Viae Appia, or Appian Way, built by a censor named Appius Claudius Caecus for the Samnite Wars. This road connected Rome to Brundisium (Brindisi).

2. Viae Militares

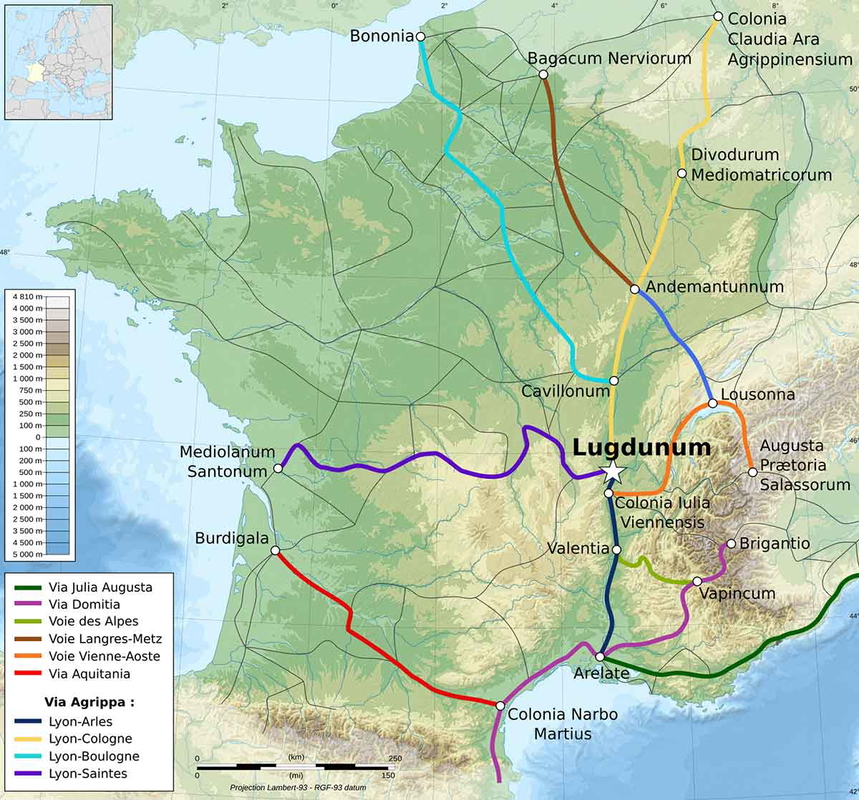

As the title implies, Viae Militares served as nearly exclusive roads for the legions. Built a bit rougher than Viae Public, these aided rapid deployments of legions, messengers, and supplies. Besides connecting fortresses and deployment, Viae Militares often ran through disputed areas or remote areas, aiding in control.

These roughs frequently lacked the Viae Publica’s better construction. However, they could withstand heavier use. They existed for rapid movement and communication. Funded by provincial/military governors, unofficial use could mean penalties. Famous examples of Viae Militares include the Via Domitia, built in 118 BCE, connecting Italy with Spain via southern Gaul. The Via Diagonalis from the 1st century CE connected Singidunum (Belgrade) to Constantinople. This road featured two stone-paved lanes, a rarity among Roman roads.

3. Viae Privatae

Rome’s third road, the Viae Privatae, or private road, connected villas, estates, and other holdings. Unlike their better-built and famous cousins, Viae Privatae’s construction quality varied. Surfaces ranged from compressed, crushed stone to simple paving. The wealthier the landowner, the better the quality of the road.

Landowners could have cippi, or boundary stones, put down. These inscribed stones marked private land, restricting access. Viae Privatae offer a glimpse into landowner life as part of their routine.

4. Viae Vicinales

When translated, Viae Vicinales means neighborhood roads. These narrow byways joined farms, settlements, and smaller estates. Like Viae Privatae, the local officials kept these roads in shape. Their surfaces, like the former, often consisted of packed earth and occasionally paving. Local settlements depended on the Viae Vicinales to move farm goods, get to market, or get around. Under the Roman legal system, these roads fell under Roman law and couldn’t be blocked. Today, these essential but unnamed roads are found as field boundaries or trenches.

The practical Romans built their roads to last. They knew that better communication and commerce kept their empire together.