The Gospels of Luke and Matthew tell the nativity story differently. Though the two accounts are easily pieced together into a coherent narrative, their writers clearly had different priorities. Still, one detail both chose to leave out was the specific type of structure in which Jesus was born. Matthew says nothing about the newborn Jesus’s immediate environs, and Luke merely mentions that he was placed in a manger without naming the type of shelter. Under what kind of roof did Jesus draw his first breath? And, does it matter?

The Manger in Luke’s Gospel

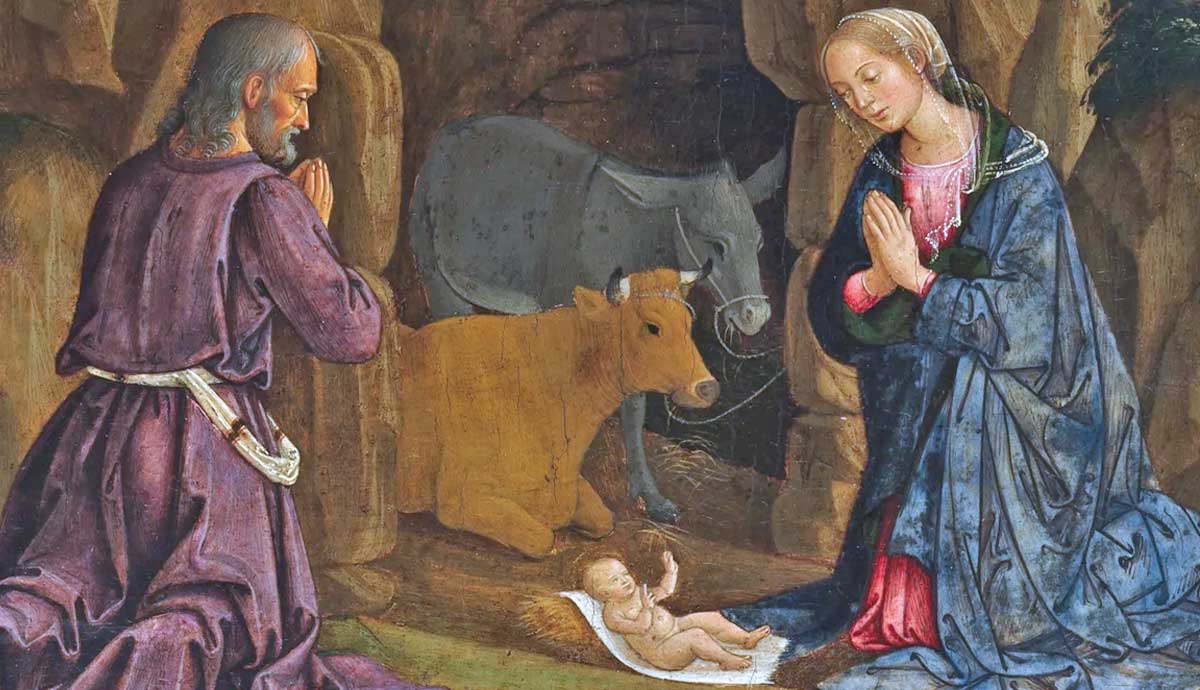

The association of mangers with animal shelters is understandable, since this is where farm animals are found in much of modern experience. But there is no stable or barn mentioned in Luke’s nativity story, and it appears that its prominence in modern nativity scenes is a relatively late development. In the absence of a viable alternative, the assumption would be warranted. But there is a strong tradition in favor of a cave—that is, a cave used as a stable—and there is nothing in Luke’s wording that would preclude the possibility.

Was a Cave Used as a Stable?

Visitors to Bethlehem routinely follow a stairway into a cave below The Church of the Nativity, where a star inside a small cutout in the cave’s side marks the traditional spot where Mary gave birth to Jesus. A barn-like shelter would have been superfluous in such a place, since the cave itself would have provided all the cover needed for animals. Wood is not in abundant supply in that part of Israel, and shepherds and herdsmen often used caves to shelter their animals, as they do today throughout West Asia.

The cave-birth tradition also comes out in several “infancy gospels,” in which Mary gives birth to Jesus during the journey to Bethlehem. Other elements traditional to the nativity story, like Mary’s riding on a donkey, can also be found in the infancy gospel tradition. But the cave in the infancy gospels does not house domesticated animals, and there is no manger therein.

A Cave-Birth in the Infancy Gospel Tradition

The earliest account of Jesus’s birth in the infancy gospel tradition is found in the so-called Protoevangelium (or “Pre-Gospel) of James, written probably in the second century. In this account, Joseph leaves Mary to give birth in a cave with his sons (from a previous marriage) keeping watch outside while he runs to find a midwife. Mary’s donkey, a standard Christmas figure absent from the Bible, plays a role in this gospel as well. Salome, Mary’s sister, appears on the scene after the birth and enters the cave to check if Mary had indeed given birth as a virgin, presumably by learning whether or not her hymen was intact.

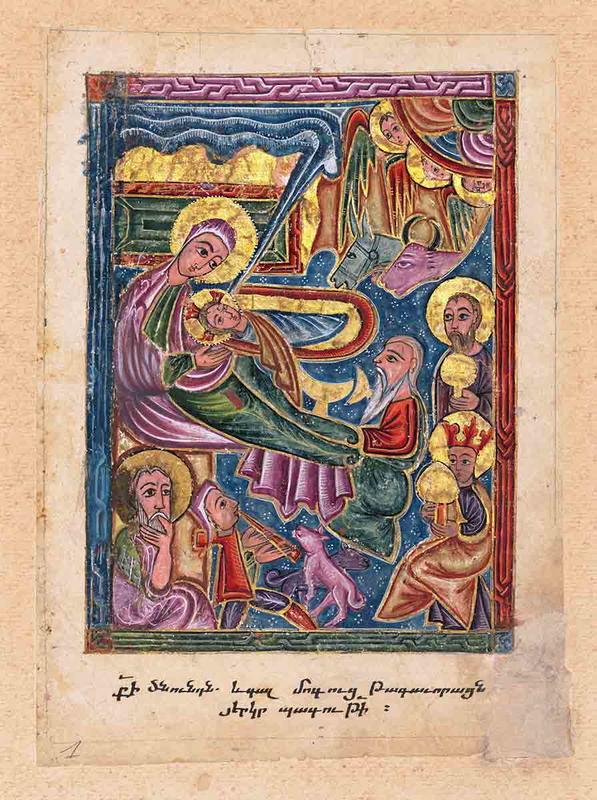

The test vindicates Mary, in a scene clearly echoing “doubting” Thomas’s encounter with the risen Jesus in the Gospel of John. The cave also appears in the Arabic and Armenian infancy gospels, named after the languages in which they survived, and in the art on walls of many Byzantine-era churches.

Emergency Birth

All three of the infancy gospels mentioned above have Mary giving birth in a cave before she arrives in Bethlehem. She feels her contractions beginning, tells Joseph she cannot go on, dismounts for her donkey (present in these stories, though absent from the New Testament), and then proceeds to give birth without anyone’s help.

The innkeeper’s absence appears at first to be an oversight. However, a close reading of Luke’s version of the story reveals he was added to the story later—indeed, even later than the donkey was added. Further, an examination of the Greek wording, in which Luke was originally written, reveals there is no “inn” is present in the story either, even though it continues to appear in modern translations. The writer of Luke knew a Greek word for “inn;” it appears later in the story of The Good Samaritan. But the word translated “inn” in Luke’s nativity narrative normally refers to a house’s spare room.

Jesus’s Possible Birth in Someone’s House

The truth is that there is nothing in the wording of Luke’s Gospel in and of itself that would preclude an assumption that Jesus was born in someone’s house—nothing, that is, except for the presence of the manger.

This is where some cultural insight can inform how the text can be interpreted. The assumption that farming and burden-bearing animals would be kept in a separate building from their owners, especially if those owners were not very well-to-do, is unwarranted if the local culture of Palestine today is taken into account. There is reason, even from within the Bible itself, to believe that the ongoing custom of keeping animals in a lowered, separate section of a house at night was even more common in the land of Israel in biblical times it is today in many Mediterranean cultures. Nights are cold in Bethlehem during the winter months. Animals provide a source of heat that the frugal would not want to waste. Bringing them inside also prevents theft.

Animals Serving a Newborn

If one begins with the assumption that Mary gave birth in a house, Luke’s version of the story can be read in two possible ways. It could be that this house’s extra room was occupied, and so Mary and Joseph were housed in the main area of the house. There was “no room” for them in the back room, so Jesus ended up lying in a manger. Another possibility allowed for by Luke’s wording is that there was “no place”—the most common translation of the Greek word topos in the text—for Mary and Joseph to lay the baby in the extra room, so they brought him out and laid him in the manger, near the animals.

Babies like to be warm and have their arms held close to their bodies, so the convex shape of the manger along with the animals’ body heat would have served the newborn well on a chilly night in Bethlehem.

How Luke’s Nativity Story Highlights Those Who Welcomed Jesus

The Gospel of Luke is especially interested in showing that the poor and truly pious received Jesus as God’s Chosen One. In Luke’s nativity story, for example, everyone from the shepherds to Joseph to Mary’s relatives Elizabeth and Zechariah to a “righteous and devout” holy man named Simeon to a prophetess named Anna at the Temple recognize the baby Jesus as the Messiah of Israel. These types of people are portrayed as believing Mary’s implausible claim that she had become pregnant without the help of a man.

By contrast, Matthew’s nativity story includes episodes of resistance. Matthew shows Joseph initially resolving to divorce Mary. The account of Herod’s slaughter of the innocents is in Matthew only. These scenes are absent in Luke.

A rejection of a pleading holy family at the door of an inn, thus, fits in Matthew but not in Luke. A nativity in the modest home of a pious family, however, fits Luke’s theme perfectly.

Origins of the Date-Palm Tree Tradition

Another infancy gospel usually called Pseudo-Matthew, which survives in Latin, has Mary giving birth to Jesus in a cave in agreement with the infancy gospel tradition. But in a later scene, Mary and Joseph are once again on the road, this time on their way to Egypt in flight from King Herod. An exhausted Mary stops to rest under a date-palm tree. Reclining under the tree’s branches, Mary wishes aloud she could eat its fruit, which she sees growing above her out of reach. The infant Jesus, who has already shown his ability to speak in a previous story (in that case pacifying cave-dwelling dragons), commands the tree’s branches to bend so that his mother can pick their fruit.

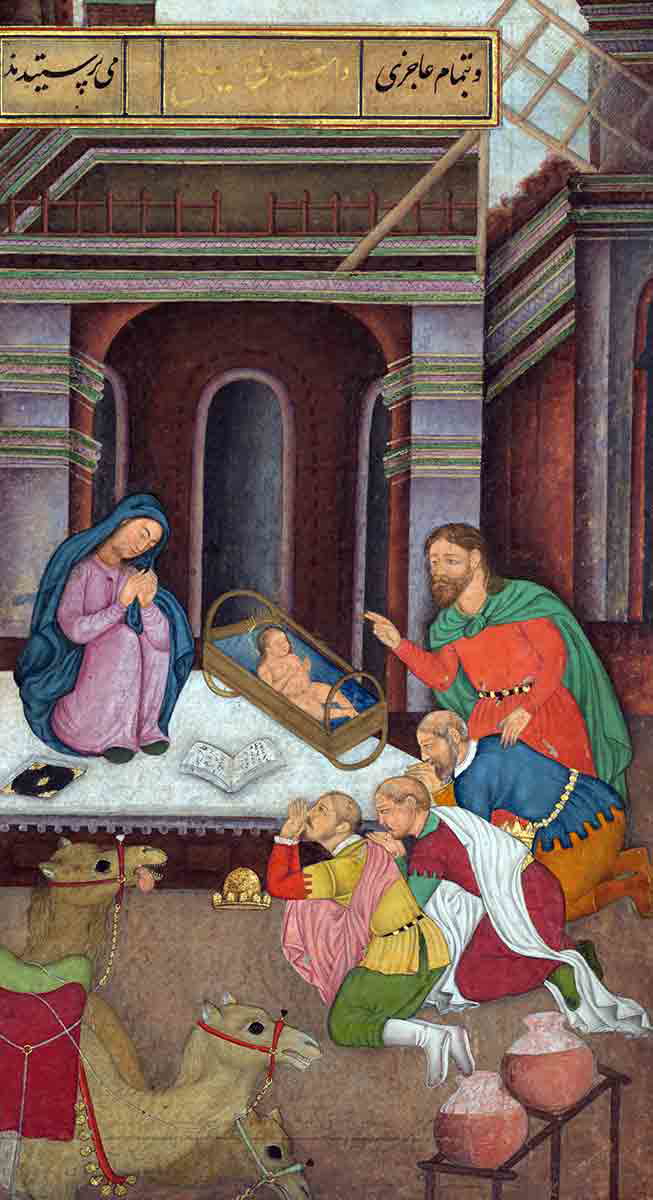

This story appears to be echoed in the Qur’an. However, in the Islamic telling Mary gives birth to Jesus under the date-palm tree. The Qur’an’s infant Jesus also speaks, hinting at another connection to the infancy gospel tradition.

Does It Matter Where Jesus Was Born?

The various imagined locations of Jesus’s nativity are symbolically meaningful. The stable speaks to Christians today of Christ’s humility—that God is especially present among the lowly. The cave adds an ascetic, mystical aura to his humble beginning. The tree in Islamic tradition, meanwhile, evokes other stories of food and water miracles from the lives of the prophets. In particular, Mary’s experience in the Qur’an has clear similarities with that of Hagar, wife of Abraham and mother of Ishmael, who also received divine provision while her infant son lay in the shade of a tree in the wilderness.

Yet, the writer of Luke’s gospel—the most widely-read and oldest version of the Christmas story—may have imagining Jesus’s nativity in home of a hospitable, working-class, family in first-century Palestine. Admittedly, a home-birth is more mundane than the other suggestions above. But for those who think even normal folk could use a Messiah, it has its appeal.