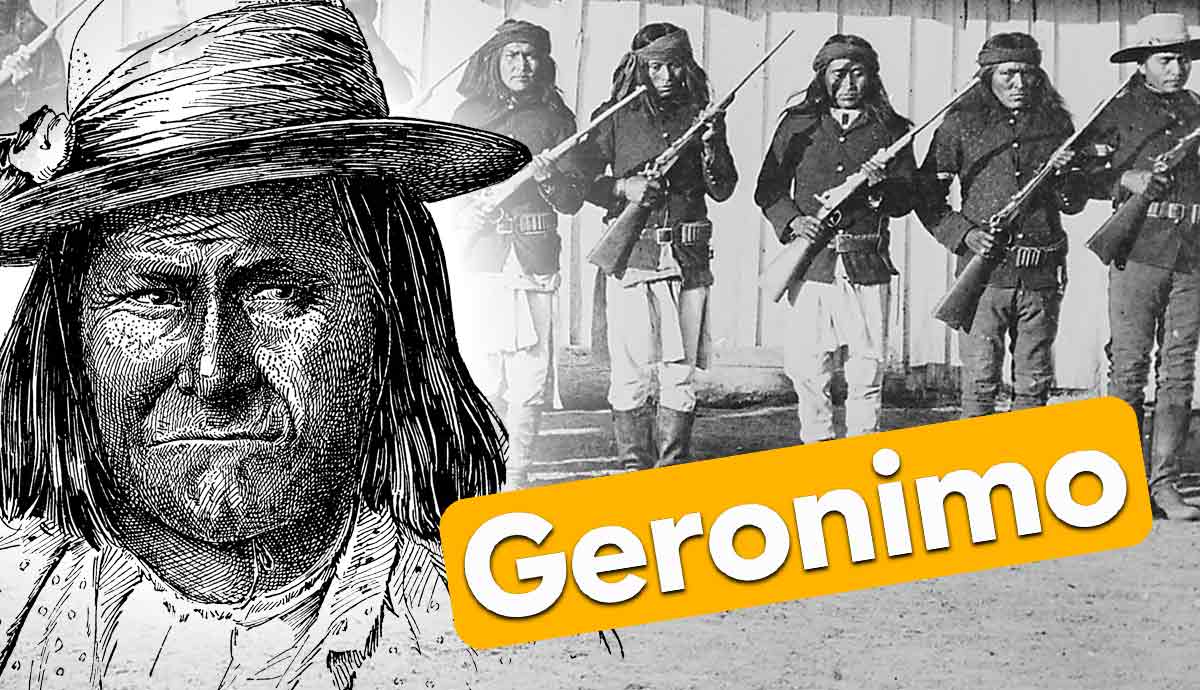

When swimmers yell “Geronimo!” as they jump off the diving board and cannonball into the pool, do they know whose memory they are conjuring? While his name may be an everyday exclamation in American English, Geronimo, the man, is less recognizable. A talented hunter and warrior, Geronimo took up arms to defend his people and their homeland against the incursion of the United States government. One of the last holdouts of the United States’ attempts to remove Native Americans, Geronimo’s fierceness and commitment to the Apache people are indelible.

Life on the Move

Goyahkla, the child who would later be known as Geronimo, was born in June 1829. His birthplace was No-Doyohn Canyon in Mexico, which today is in Southwestern New Mexico. Goyahkla, meaning “one who yawns,” was a member of the Bedonkohe, a division of the Chiricahua Apache tribe. The Bedonkohe was a small group with many enemies, including Mexicans, Navajo people, and the Comanche tribe. Eventually, this list of enemies would include the United States government.

A big reason for these tense relationships was the fact that the nomadic tribe often raided for survival. Resources such as livestock, horses, food, ammunition, and weapons were captured as a result of this practice, which had been part of the Chiricahua culture for centuries. Goyahkla proved himself a talented hunter and fighter, and was admitted to the warriors’ council in 1846. He married at the age of 17, and he and his wife, Alope, had three children.

“No Gun Will Ever Kill You…”

In 1858, Goyahkla was on a trading trip in Janos, Mexico, with several other men. When they returned to their camp, they found that the women and children who had remained encamped had been attacked and massacred by Mexican soldiers from a nearby town. The Mexican government and people had a longstanding fractious relationship with the Apache, at times offering cash for scalps of Apache men, women, and even children.

More than 100 women and children were killed, including Goyahkla’s mother, wife, and three children. In keeping with tradition, Goyahkla burned the belongings of the deceased and went alone into the wild to grieve. While he was alone in the wilderness, Goyahkla claimed to have heard a voice that promised him, “No gun will ever kill you. I will take the bullets from the guns of the Mexicans…and I will guide your arrows.” He took this as encouragement to exact revenge on those who had taken his family and people.

When he returned to his people, Goyahkla took an even stronger leadership role. Devastated over his loss, he vowed revenge, supported by a force of approximately 200 other men. Over the next decade, Goyahkla led his men on a campaign of revenge against the Mexicans. He earned his more recognizable name, Geronimo, during a pitched battle with the Mexicans. Mexican soldiers attempted to appeal to St. Jerome, or “Jeronimo” in Spanish. Their cries of “Jeronimo!” would become their slayer’s new nickname, one which he was said to accept.

A Changing Enemy

After the conclusion of the Mexican-American War and the discovery of gold in the Southwestern United States, American settlers began streaming into areas of the country that were once part of Mexico—territory that was frequented by the Chiracahua. This new presence threatened the existence of Geronimo’s people as efforts to remove Indigenous people from their homelands began to spread. Apache attacks on travelers and settlements began to ramp up as the Apaches attempted to not only continue their raiding culture but to halt incursion. Apaches and Americans escalated to taking prisoners, and a series of events known as the Apache Wars began.

Geronimo had remarried (he would have several wives over his lifetime, with sources ranging in estimates from seven to over a dozen) and fought under his father-in-law, Cochise, and legendary chief Mangas Coloradas. There were few open battles during the conflict, which lasted 24 years, but many ambushes and raids. In 1872, much to Geronomio’s disappointment, Cochise negotiated with General O.O. Howard to end the conflict. As a result, the Apache were granted reservation land in what is now Southeastern Arizona. Geronimo did not adjust well to reservation life and left frequently.

After Cochise’s death in 1874, likely from stomach cancer, relations between the United States government and the Apache tribe disintegrated. The reservation was moved north, away from traditional Apache homelands, in order to allow for American settlements. Geronimo continued to leave the reservation frequently, often raiding during these absences. More and more Apache were leaving the reservation, and the Americans began to negotiate with new leaders, Juh and Taza, Cochise’s son, in an effort to return people to the reservation system.

Geronimo interfered in these discussions, pitting Juh and Taza against one another. Geronimo often spoke for Juh, a lifelong friend, due to the latter’s stutter. Juh refused to move to the new San Carlos reservation, leaving with Geronimo and two-thirds of the Chiricahua people. When Indian Agent John Clum learned Geronimo was to blame for the broken deal, he issued a call for his arrest.

A Wanted Man

Geronimo was arrested at the Warm Springs Reservation near Winston, New Mexico. As a result, the reservation was closed, and the Warm Springs Apaches were moved to San Carlos with the other Chiricahuas. His arrest did little to stem Geronimo’s exodus from the reservation. In 1881, Geronimo struck out again with his followers. For the next five years, he eluded the US Army. Legions were sent after him, and at one point, nearly a quarter of the US Army’s troops were searching for him, in addition to numerous “Indian scouts.” Geronimo and his followers were considered the last major Indigenous force to hold out against US occupation in the West.

General George Crook was appointed to subdue Geronimo’s forces and knew he was up against a tough enemy. When asked to describe the Chiricahua, Crook said that they had “acuteness of sense, perfect physical condition, absolute knowledge of locality, almost absolute ability to persevere from danger.” He called them the “tiger of the human species.” The US Army even colluded with their old rivals, the Mexican government and the two parties gave one another permission to cross their shared border indiscriminately when in pursuit of the Chiricahua.

Though Crook was a man of admirable military skill, he was somewhat impulsive when it came to hunting. One day, while on the trail, he ventured off, tracking an animal, and came face to face with Geronimo and his people. Though Geronimo had the perfect opportunity, he didn’t kill the general that he called “The Tan Wolf” due to his khaki wardrobe. Geronimo had realized that there was no end in sight. The US army had virtually endless resources at its disposal, and a few dozen Apache warriors would not be able to hold them off forever. Geronimo took the opportunity to start negotiations with Crook. An agreement was reached that granted the Chiricahua a reservation at Turkey Creek in Arizona.

Peace persisted for approximately a year before tensions came to a head once again. The US government attempted to assimilate the Apache, encouraging farming and outlawing many practices of Apache cultural life, such as the brewing of a traditional alcoholic beverage, tizwin. Miscommunication further contributed to these issues, as translation often required Spanish as an intermediary between Apache and English.

Geronimo decided it was time for one last run. Along with 36 followers, he left the reservation, heading to Mexico. A $25,000 bounty was placed on Geronimo, and his band of three dozen was pursued by 9,000 US soldiers, Mexican soldiers, and assorted volunteers. General Nelson Miles of the US Army proposed an idea to lure Geronimo in for surrender. He suggested banishing the remaining Chiricahua at San Carlos, who had family in Geronimo’s fleeing band, to prison in Florida. When Geronimo heard of this threat, he met with Lieutenant Charles Gatewood to negotiate a surrender.

The Warrior Falls

In the summer of 1886, Geronimo became the last Chiricahua to surrender to the United States. The US followed through on their threat of banishment to Florida, and Geronimo would be among those deported. The long train trip took its toll on the people, as did the poor sanitation in the disease-ridden prison. Geronimo spent time in Florida, then Alabama, as a prisoner of war. A legend among white Americans who had read of his exploits in newspapers, he spent time in Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show and rode in Theodore Roosevelt’s election parade. While there, Geronimo asked Roosevelt for his people to be returned to the Southwest. His request was denied.

An artist who visited the imprisoned Geronimo to paint him stated that his subject showed him over fifty bullet wounds on his body, explaining, as the voice in the wild once had, that bullets would not kill him. Instead, Geronimo died in 1909. He acquired pneumonia after a drinking spree resulted in him spending the night in a ditch after falling off his horse. In 1913, after 27 years in confinement, his people were given the option to return to the Southwest, to the Mescalero Reservation. Today, there are thousands of Apache people living in the United States, the very people which Geronimo fought with vengeance and commitment in his heart to save.