Trying to unravel the knotted webs of Cleopatra’s family drama is a Herculean task. The Ptolemaic Dynasty was not just about ruling the land of the Nile—it was about keeping their family tree nice and circular by marrying their siblings. Cleopatra VII, the queen we all know and whose mystique continues right on to today, came from a family so tangled that historians need flowcharts just to keep the players straight. Her siblings weren’t just family—they were also frenemies, co-rulers, and, occasionally, barely tolerated spouses. The fact is, no one is even quite sure how many siblings there actually were in Cleopatra’s generation. Here we’ll take a look at the ones we know (or think we know) about.

Confusion Over Her Mother

It is nearly impossible to make an exhaustive list of siblings when historians can’t pin down who exactly Cleopatra’s mother was. Historical records didn’t bother to jot down her name, leaving scholars to sift through theories thicker than the silt of the Nile. The most commonly posed theory elevates Cleopatra V, the first wife of Ptolemy XII as the most likely candidate for Cleopatra’s mother. However, Cleopatra V disappears from the historical record sometime before 68 BCE, leaving a tantalizing gap just big enough for speculation. Did she die before Cleopatra’s birth in 69 BCE, or shortly after? Was her exit more political than biological?

Another possibility is that Cleopatra’s mother was a concubine of Ptolemy XII. Ptolemy XII, with the sobriquet “Auletes” and Cleopatra’s father, himself was the son of Ptolemy IX and one of his concubines—an arrangement that added some much-needed genetic diversity to the otherwise alarmingly inbred Ptolemaic family tree. The third theory is that Cleopatra’s mother might have been Ptolemy XII’s second wife, whose name history didn’t deem worthy of preserving. This mystery woman could also have borne Cleopatra’s younger siblings, Arsinoe IV, Ptolemy XIII, and Ptolemy XIV.

There is speculation that Cleopatra’s paternal grandmother—or possibly even her mother—could have been indigenous Egyptian, offering yet another fascinating layer to the family’s multicultural heritage. In this case, they would have been a lesser wife, probably from the noble priestly caste, but not equal in power to a pharaoh’s sister/half-sister wife. In 2009, a BBC team claimed that skeletal analysis of bones found in Turkey allegedly belonging to Arsinoe IV hinted at African ancestry, sparking a lively debate about Cleopatra’s racial identity. However, these debates are more about modern preoccupations with race than anything the ancient world cared to discuss. Categories like “white” and “Black,” so central to contemporary identity, simply didn’t exist in antiquity. Cleopatra was, above all, a queen of Egypt—an identity rooted in her political and cultural role, not in the anachronistic racial labels modern societies try to impose.

Ultimately, the ancients weren’t losing sleep over Cleopatra’s maternal or racial background. After all, whether her mother was a queen, a concubine, or a mystery woman who vanished into the sands of history (or some combination of all three), Cleopatra’s brilliance, political savvy, and command of her world weren’t inherited through the bloodline—they were entirely of her own making.

The Boys

Cleopatra’s brothers, Ptolemy XIII and Ptolemy XIV, weren’t just her younger siblings—they were also her husbands. Ancient Egypt, in its divine wisdom, had a knack for blending family ties with royal duty, and Cleopatra’s reign was no exception, despite her Macedonian Greek background. According to the Ptolemaic playbook, based on the reigns of earlier dynasties, siblings marrying each other was not just acceptable—it was preordained. This was not about romance or even politics in the way we would imagine—it was about embodying the divine harmony of Isis and Osiris, the ultimate sibling couple of Egyptian mythology.

Cleopatra married Ptolemy XIII after their father’s death when she was still a teenager (he may have been as young as 13 when they wed). At first, they ruled Egypt together, but the sibling bond quickly frayed. Ptolemy XIII, spurred on by his advisors, turned against Cleopatra, forcing her into exile. He then married another sister, Arsinoe, setting her up as his queen instead.

Cleopatra was no wilting lotus; she returned with Julius Caesar and his army, sparking a civil war. In the end, Ptolemy XIII fled during a decisive battle, only to drown in the Nile—a dramatic exit for a boy king who underestimated one sister’s cunning and thought he could simply trade her for another.

Following Ptolemy XIII’s untimely demise, Cleopatra married her youngest brother, Ptolemy XIV. He was even younger than her first husband—likely just ten or eleven years old at the time—making it clear that this was more about checking the boxes of tradition than forming a functional partnership. Ptolemy XIV co-ruled with Cleopatra for a few years, but his reign (and life) came to a suspiciously abrupt end. Shortly after Cleopatra bore Julius Caesar’s child, Ptolemy XV Caesarion, Ptolemy XIV died—almost certainly done away with on Cleopatra’s orders. Now, she had a child to protect and elevate, one she could raise to be much more trustworthy than a half-brother.

To those wondering whether Cleopatra shared more than a crown with her brothers, history keeps things murky. There is no evidence she had any pregnancies by either of them, unlike earlier Ptolemaic rulers whose sibling marriages often resulted in offspring. Considering their young ages and Cleopatra’s ruthless approach to securing power, it is likely these unions were marriages in name only. After all, Cleopatra seemed perfectly fertile in her relationships with both Julius Caesar and Mark Antony, the Roman heavyweights with whom she had children and shared a much more storied—and historically scrutinized—intimacy. The boys, meanwhile, were not much more than pawns in Cleopatra’s game, illustrating the bizarre and ruthless dynamics of Ptolemaic royalty.

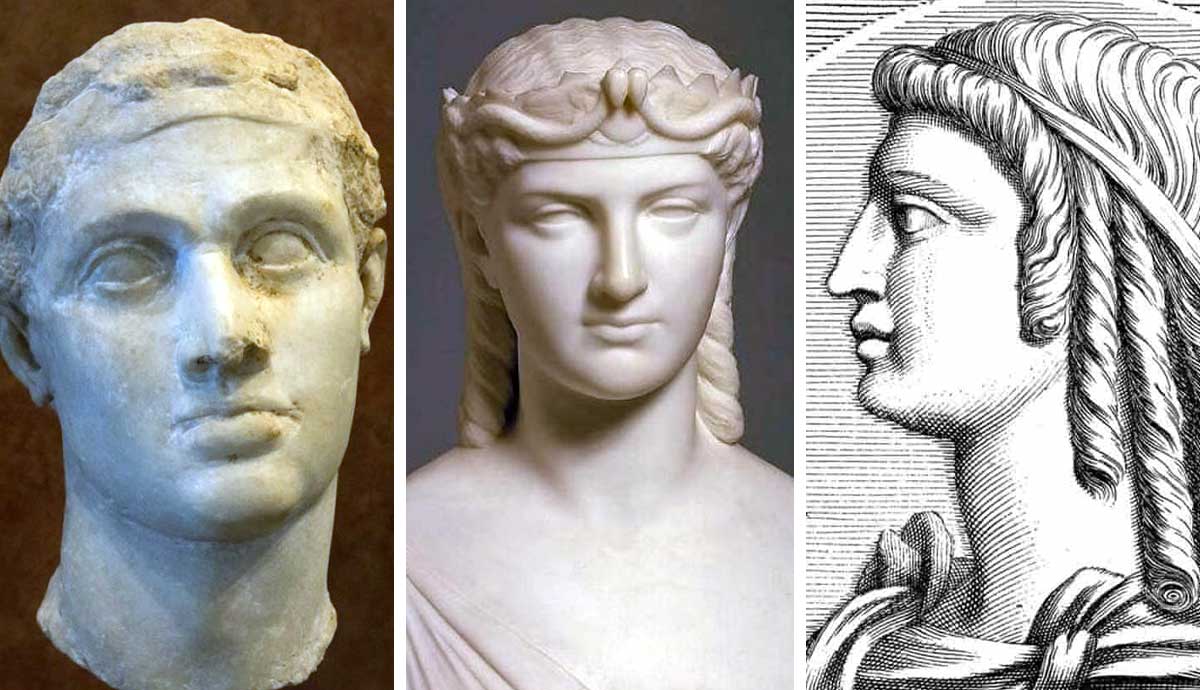

The Girls: Berenice, Arsinoe, and Tryphaena(?)

Cleopatra’s sisters—Berenice IV, Arsinoe IV, and the enigmatic Cleopatra Tryphaena—were a fierce trio who navigated the treacherous politics of the Ptolemaic Dynasty with as much cunning as their more famous sibling. These women didn’t just orbit Cleopatra’s story, they carved out their own legacies, often bloody, always dramatic, and sometimes downright baffling.

Let’s start with Berenice IV, possibly the eldest and most overtly defiant of the bunch. When her father, Ptolemy XII Auletes, fled to Rome in 58 BCE with young Cleopatra in tow to escape a popular uprising, Berenice seized the throne and ruled Egypt solo…almost solo. The Egyptian people pressured her into marrying, but her first husband, Seleucus VII Kybiosaktes, was a spectacular flop. Berenice dealt with this unwanted partner decisively: she had him killed.

Her second marriage, to Archelaus, fared slightly better, but the union was cut short when Auletes returned in 55 BCE with Roman military support. Ptolemy XII’s forces swiftly overpowered Berenice’s army, and he had his daughter executed, much as she had done to her first husband. Berenice’s downfall was a grim reminder that even the most assertive of Ptolemaic women could fall victim to their dynasty’s ruthless politics.

Then there was Arsinoe IV, the youngest sister and arguably Cleopatra’s most resilient rival. Despite her youth—likely just 16 or 17—Arsinoe made waves during the Alexandrian War. After Cleopatra’s fallout with her younger brother-husband, Ptolemy XIII, Arsinoe allied herself with his faction and declared herself queen.

Her brief reign included one of the boldest moves of her life: orchestrating a water siege that forced Julius Caesar to flee for his life. Arsinoe’s troops, under her command, poured seawater into the canals that supplied Caesar’s cisterns, cutting off his access to fresh water. As Caesar’s position grew desperate, Arsinoe’s forces even managed to seize him. Faced with capture, Caesar ditched his purple cloak and armor—a humiliation in itself—and dove into the sea to escape, swimming to a nearby Roman ship. While her victory was temporary, it was nothing short of extraordinary for someone barely out of girlhood.

Unfortunately, Arsinoe’s triumphant moments were short-lived. After her forces were defeated, she was captured and paraded through Rome in Caesar’s triumph, a spectacle designed to humiliate her. Exiled to a temple in Ephesus, Arsinoe’s relative safety didn’t last. In 41 BCE, Cleopatra, now firmly in control and ever wary of rivals, ordered her younger sister’s execution. Even in death, Arsinoe’s story captured imaginations—her alleged skeleton, discovered in Turkey in the area that once housed a goddess’s temple, has sparked debates about Cleopatra’s heritage and Arsinoe’s own legacy as a young woman who dared to defy the Roman Empire.

There is a wildcard of a sibling: Cleopatra Tryphaena. Was she Cleopatra VII’s older sister, or was she her mother/stepmother? Historians have been arguing about this for centuries. Some believe she co-ruled with Berenice IV during their father’s exile and died mysteriously in 57 BCE. Others suggest she was Cleopatra V Tryphaena, Ptolemy XII’s wife, meaning she would have reappeared on the historical record long after she supposedly vanished in 69 BCE.

Modern novelists, meanwhile, have leaned into the idea of Tryphaena as Cleopatra VII’s power-hungry older sister. These portrayals often paint her as a Machiavellian figure, using her cunning and ambition to manipulate events from behind the throne—or, in some cases, to outright seize it. Whether she was a sister or a stepmother, Tryphaena’s legacy remains as elusive as it is fascinating, a puzzle piece that refuses to fit neatly into Cleopatra’s already complicated family tree.

Could There Be More?

Figures like Charmion and Iras, Cleopatra’s noted devoted attendants, hint at the power dynamics within the palace and its harem. Ancient sources like Plutarch and Dio Cassius describe Charmion and Iras as key players in Cleopatra’s final moments, staying by her side in death as they had in life. According to Plutarch, it was these two women—alongside Mardian the eunuch—who directed affairs during Cleopatra’s downfall, while Antony had essentially become a paranoid shadow of his former self.

Cleopatra’s final act of defiance, when she and her attendants locked themselves in and prepared for death, is legendary. Plutarch writes that Caesar’s men found Cleopatra lying on a bed of gold, adorned in royal finery, with Iras and Charmion close by. When someone asked Charmion angrily if their actions were the decisions of wise women, she famously replied, “Extremely well, and as became the descendant of so many kings,” before collapsing at Cleopatra’s feet.

Modern retellings, like Jo Graham’s Hand of Isis, go a step further, imagining that Charmion and Iras were more than loyal attendants—they were Cleopatra’s half-sisters, daughters of Ptolemy XII, and women of the harem. While this is purely speculative, it underscores how the Ptolemaic dynasty’s sprawling familial ties and harem politics remain a rich ground for both historical inquiry and imaginative storytelling.

The harem, or per-aa was not just a residence for the royal family but was another relic from Egypt’s ancient dynasties that the Ptolemies adopted (much like they did with sibling marriage). It was a sprawling complex that housed government officials, military headquarters, and even a major temple with its own priesthood. Within this labyrinth, a woman could rise from obscurity to immense influence, especially if she bore the king a son who became the next ruler.

So, could there be more children of Ptolemy Auletes? Absolutely. The Ptolemaic Dynasty’s intrigue was not limited to the throne room but extended into the harem, the palace, and beyond. The women of Cleopatra’s world—be they sisters, attendants, or mothers—were key players in a drama as complex and captivating as the queen herself, though so far they have remained unnamed and deemed unimportant by the archivists of old.