Emerging in the context of Henry VIII’s English Reformation, the Puritans, a loosely knit community of English protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries, believed that the Church of England preserved too many remnants of Roman Catholicism. They sought more radical reform – a ‘purified’ biblically governed community that reflected the scriptural principles of ‘true’ religion. Faced with persecution in England, many Puritans sought religious freedom in the ‘New World’, where they founded colonies that deeply influenced the political and cultural foundations of the future United States.

Puritan Beginnings

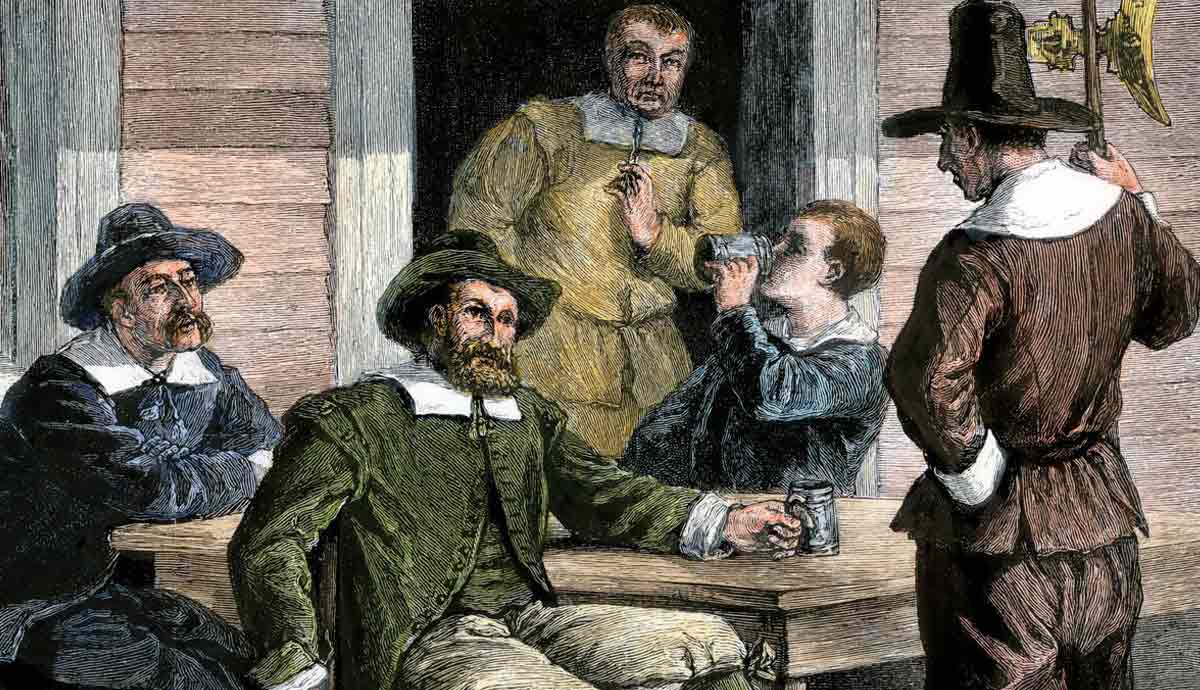

In 17th-century England, church and state were inseparable: membership of the Church of England was compulsory. Attendance at Sunday services was legally enforced. Church courts exercised authority over moral and religious conduct, punishing offenses such as adultery, blasphemy, or failure to pay church tithes with public penance or excommunication (Hill, 1982).

The roots of Puritanism trace back to the 1520s, in the context of growing radicalism following Henry VIII’s break with the Catholic Church. Unhappy with the Church of England, most Puritans sought to reform from within, rather than break from it. In this regard, they first emerged as a movement attempting to “purify” the church of residual Catholic “idolatry” – rejecting the continuation of ecclesiastical hierarchy, clerical vestments, and sacred images (Hall, 2019).

Puritans pushed for a simpler, scripture-based mode of worship. They aimed to ‘complete’ the reformation by abolishing hierarchical church structures and promoting lay control (Hill, 1982). Their vision was of a church and society ruled not by monarchs or clerics but by the direct biblical authority of God’s word.

What Is Puritanism?

Despite its profound historical impact, Puritanism is a ‘problem’ insofar as it defies precise definition. Scholars have variously described it as a religious, cultural, and political movement (Van Engen, 2013).

Lacking a unified doctrine, Puritanism was unified instead by shared values and core convictions: strict personal discipline, deep engagement with scripture, and the idea of life as a divine calling. They shared a commitment to reading and studying the Bible, attending sermons, and observing the Sabbath. The bible was treated as divine “law” (Hall, 2019).

The Puritans emphasised a “double calling” – one to divide service to God and the other to their worldly vocation, in the service of God. Faith was not limited to Sunday worship but lived out daily – through strict religious observance, disciplined moral conduct, and the banding together of the godly.

Thus, Puritanism functioned less as a denominational creed and more as an all-pervasive religious sensibility rooted in Reformed-style Protestantism.

Everyday Puritan Beliefs

Puritanism, then, was very much a ‘living faith’ anchored in a covenantal, personal relationship with God. This covenant demanded intense personal piety, strict moral discipline, and total obedience to God.

Central to Puritan theology was the practice of a version of Calvinist predestinarianism – the idea that God had eternally predetermined who would be saved or damned, irrespective of human efforts or merit. The concept of predestination fueled intense inward scrutiny among Puritan believers, as strict moral behavior and religious zeal became outward signs of divine election.

In this regard, the Puritan family became the nucleus of Godly society. Marriage was considered sacred, albeit with husbands as the spiritual head of the household. Wives, by contrast, were expected to show religious faith through obedience, managing the home, and piously raising children.

Beyond the family, Puritans sought to organize society according to biblical principles. They believed the government should propagate and uphold ‘true’ religion, and that scripture should influence law, politics, and public life. Their ultimate aspiration, in this regard, was the formation of a divinely ordered society – set apart from the corruption and sin of the world Cust & Hughes, 1989).

Puritans in America

In the early 17th century, facing religious persecution in England, many Puritans sought refuge abroad and a place where they could practice their faith freely. In 1608, a small group of separatist Congregationalists from northern England fled to the Netherlands. Then, in 1620, 102 separatists, later known as the Pilgrims, crossed the Atlantic on the Mayflower and founded the Plymouth Colony in present-day Massachusetts.

In 1630, a fleet led by John Winthrop brought around 700 Puritans to North America, laying the foundations of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Over the next decade, approximately 20,000 more followed. Almost all those who migrated to America from England shared a common Calvinist theology and the vision of building a godly society without compromise.

Puritan life in America emphasized religious discipline, education, and communal responsibility. Schools were established to promote biblical literacy, and in 1636, Harvard College was founded to train ministers and religious scholars. The family was central to moral instruction and social order. Over time, the Puritans of New England collectively laid the foundations of American cultural identity itself – from the vision of a divinely ordered society, to individual responsibility and the enduring belief in the redemptive power of hard work.

The Decline of Puritanism?

By the mid-18th century, traditional Puritanism had largely fragmented, giving rise to a wide range of Protestant denominations. Some of the movement’s more radical theological elements – such as strict predestinarianism – faded from prominence. Yet many core Puritan persisted and lived on within new religious and cultural contexts.

Today, modern Evangelical denominations – from Baptists to Quakers – continue to emphasize many Puritan ideals, from Biblical literalism and the supreme authority of scripture, to the importance of inner piety and belief in divine calling. Similarly, modern Congregationalist churches continue the early Puritan emphasis on local church autonomy and pursuit of lay leadership – free from the outside influence of higher authorities.

Beyond theology, the broader cultural influence of Puritanism has been profound. In particular, the Puritan emphasis on hard work, discipline, and self-reliance – sometimes referred to as the “Protestant ethic” – remains deeply embedded in the modern ‘West.’ In this regard, though the Puritan movement itself waned, its imprint continues to shape religious and civic life across the modern world.

Bibliography

Cust, R. and Hughes, A. (eds.) (1989) Conflict in early Stuart England: Studies in religion and politics 1603–1642. London: Longman.

Hall, D.D. (2019) Puritans: A transnational history. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Hill, C. (1982) Religion and democracy in the Puritan Revolution, Available at: https://democracyjournalarchive.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/hill_religion-and-democracy-in-the-puritan-revolution-democracy-2-2_-apr-1982.pdf

Van Engen, A. (2013) ‘Puritanism’, Oxford Bibliographies Online. Available at: https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/display/document/obo-9780199730414/obo-9780199730414-0198.xml