The winged hussars dominated central European battlefields for over two centuries. The elite of the Polish heavy cavalry, they were the premier shock troops of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Distinguished by the iconic wings attached to their backs or saddles, whose noise terrorized their enemies, their greatest hour came in September 1683 when they led the largest cavalry charge in history to break the Ottoman siege of Vienna.

The Legend of the Winged Hussars

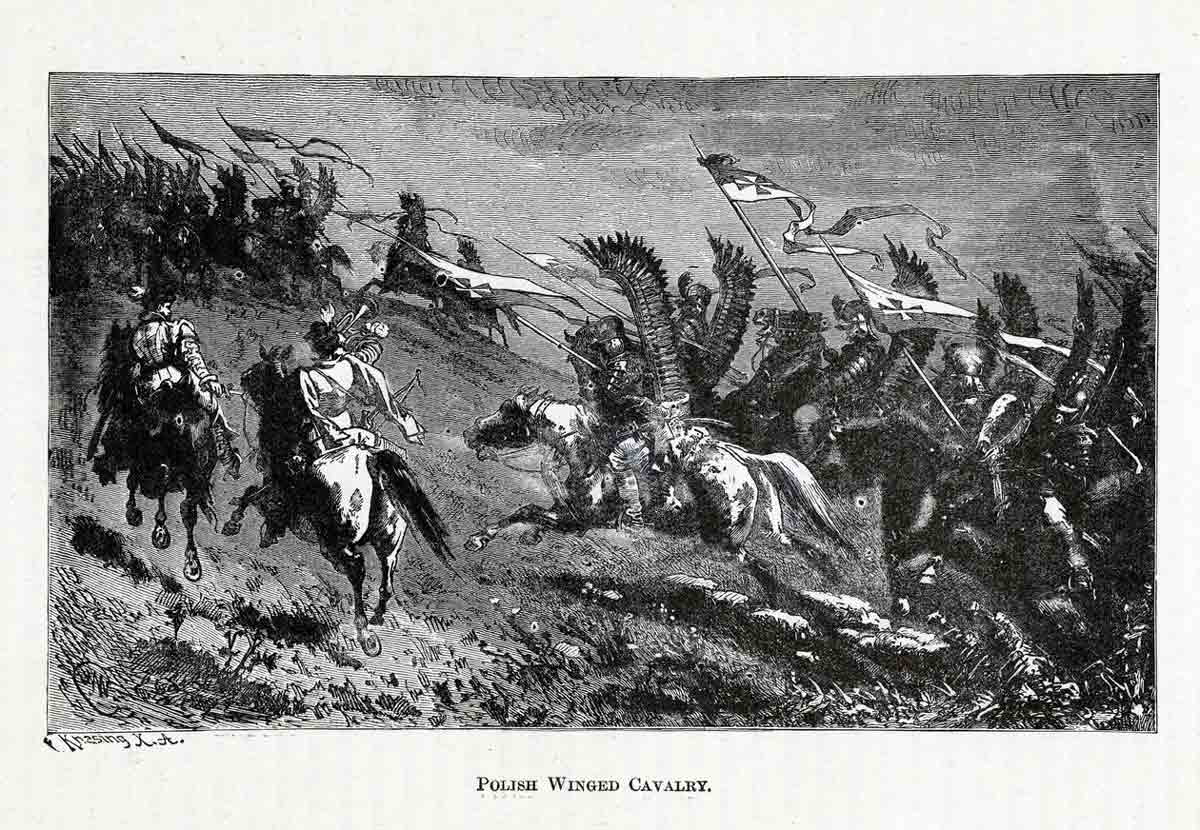

The winged hussars were the distinctive heavy cavalry of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Although nominally active from 1503 to 1776, their golden age was from the 1570s until the end of the 17th century. They earned their name from their trademark wings that were mounted on the back of their armor or saddle. They loomed above the rider and were intended to demoralize their enemies when they charged.

The winged hussars fought in every major battle involving the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth between the 16th and 18th centuries. Although most celebrated for their participation in the relief of Vienna against the Ottoman Turks, the winged hussars fought against numerous other enemies. Sweden and Russia were regular foes as were the Tatar raiders. Wherever danger was, the lances of the hussars were soon to follow.

As heavy cavalry, they are remembered as probably the most effective on central and eastern European battlefields in the early modern period. The early modern period saw the Commonwealth beset on all sides in endless conflicts. Polish kings campaigned against Germans, Austrians, and Czechs on the western border and Swedes to the north. The Russians became an increasing threat to the east while to the south they clashed with the Ottoman Empire and Crimean Khanate as well as rebellious cossacks.

Origins and Formation

The word hussar was first used to describe Serbian mercenary lancers who were frequently used against Ottoman cavalry. In the late 15th century, the Hungarian king Matthias Corvinus raised his own regiments of hussars and their effectiveness on the battlefield soon inspired other kingdoms to copy them.

The first official Polish hussar unit was formed in 1503 at the command of the Polish parliament or Sejm in response to increased raiding by the Ottomans on their southern frontier. The initial recruits were Hungarians, though Poles were also invited to join. Hussars were traditionally a light cavalry unit and this is how they are known outside the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The endemic fighting against the Ottoman Empire prompted changes to the light cavalrymen. The Hungarians were first to adopt shields and armor for their hussars which still had a use against the Ottomans and Crimean Khanate. In the west firearms were slowly making armor obsolete but the preference for the bow in the east still gave armor a function.

During the mid-1500s, the Polish hussars were gradually transformed into a heavy cavalry unit copying the Hungarian reforms. It is from the late-1500s onwards that the winged hussars adopted their distinctive appearance. Stephen Bathory reorganized his royal hussars into an armored cavalry formation with lances after his election as King of Poland in 1576. By the 1590s all Polish hussar units were similarly equipped.

Distinctive Weapons and Armor

The winged hussars gained their name from their distinctive dress. The most famous part of this was the wings attached to the back of their saddle in an angel style effect. The feathers on these were from raptors; birds of prey. Observers reported an eerie buzzing sound when the hussars charged and the wind whistled through the feathers. This and their ostentatious appearance made for a terrifying combination when they charged into battle. Officers were usually distinguished by the pelt of an animal such as a bear, wolf, or lion.

Hussars were expected to provide arms and armor for themselves and their retainers. The lance was their main weapon, longer and sturdier than those used by Balkan or Hungarian horsemen. Swords were typically carried as a backup weapon though individual choice frequently saw them equipped with a variety of secondary weapons. Some preferred warhammers, pistols, or even bows.

They were nearly fully armored, though the full regalia only weighed some 15 kilograms, not much more than modern body armor today. Mounted on strong horses, this enabled the hussars to move surprisingly quickly against rival heavy cavalry or even light Tatars. The death penalty was enforced for anyone selling a hussar mount outside of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as they were specially bred from a mix of old Polish lineage horses and Tatar imports from eastern raiders.

Key Campaigns and Battles

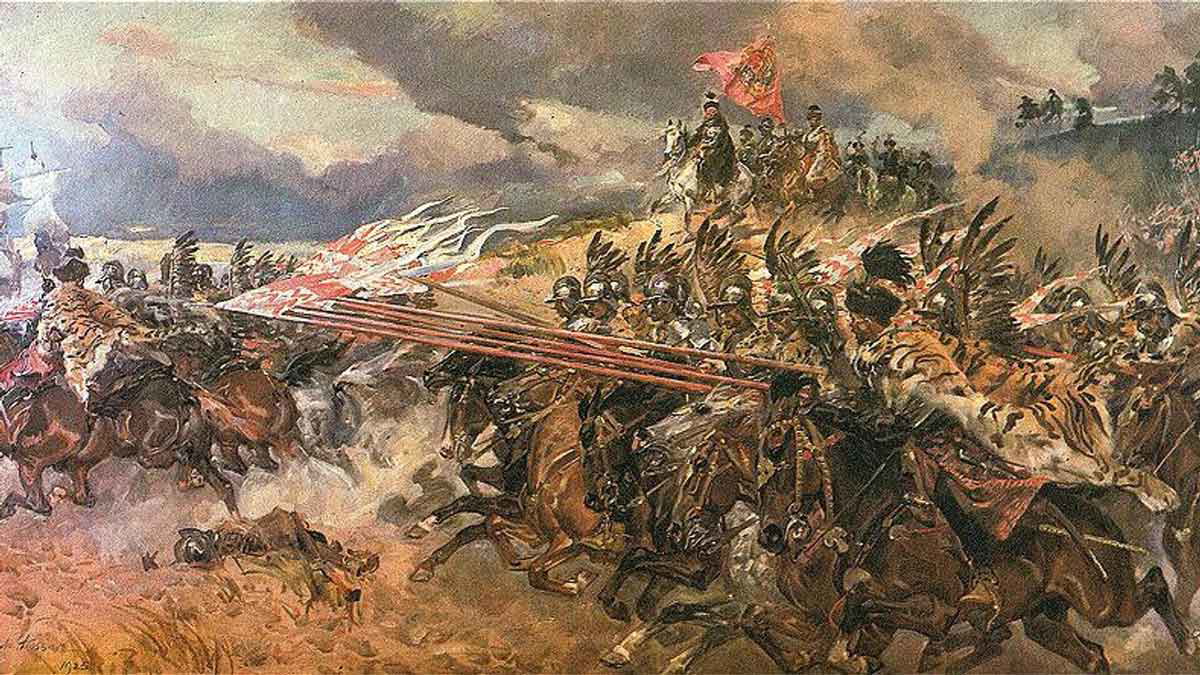

The winged hussars were celebrated for their effective charges. A block of heavy cavalry would advance at a slow pace while still loosely gathered. The advance would speed up and the hussars closed ranks as they drew closer. The charge would be repeated several times until the enemy formation routed. Any hussar who broke his lance could break off, trot back to retrieve a spare, and then rejoin his comrades. These tactics could only be pulled off by supremely trained horsemen which the hussars undoubtedly were. Hussar morale was generally high and they prided themselves on the dangers they faced.

The hussars were present at most critical battles for the Commonwealth during the 16th and 17th centuries. Their dash and daring frequently secured them victory against the odds, even when heavily outnumbered on the field. At the Battle of Klushino in 1610 during the Time of Troubles in Russia, a few thousand hussars defeated a Russian force that outnumbered them five-to-one. Outnumbered hussars repeatedly charged entrenched Russian infantry, with some units charging up to ten times. The exhausted hussars succeeded in breaking the left and centre of the Russian army, forcing the surviving Russian and mercenary troops to negotiate terms.

Their most famous victory remains the Battle of Vienna in 1683. Although fewer than 3,000 in number, the winged hussars were the most famous formation in the relieving allied army. Led by King Jan Sobieski, they formed the center of the mass cavalry charge that finally shattered the Ottoman army and saved Vienna. It remains the largest cavalry charge known to history and cemented the hussar legend.

Organization

It is fitting that the hussars retained some medieval trappings. A junior officer or towarzysz (companion) was expected to bring a retinue to war with him as knights had in previous centuries. These were usually groups of two to five other horsemen. These retainers would fight alongside their commander and formed the smallest unit in the Polish-Lithuanian army, a poczet (fellowship) or kopia (lance). Retainers would also look after supplies, tend to their master’s horses, repair weapons and armor, as well as fight in battle.

Several of these retinues would be grouped together to form a chorągiew (banner), equivalent to a modern company. It would be commanded by a senior companion who would take the title rotmistrz (riding master) with a porucznik (lieutenant) as second-in-command. A junior officer would be the chorąży (ensign) and responsible for carrying the unit’s standard. The rotmistrz’s kopia would be the largest as they included numerous musicians to help coordinate the unit on the battlefield. Different roles in the unit were filled by various towarzysz depending on their level of experience.

Most hussars were of noble birth as they would have been otherwise unable to afford the expenses of war. A hussar paid for his weapons, armor, retinue, rations, horses, fodder, and more. A popular saying was that the king only paid for their lance. The myriad number of weapons and rigorous training that hussars had to face was something only the nobility could afford.

Decline of the Winged Hussars

The hussars endured longer than many of their contemporaries. Heavy cavalry had disappeared from battlefields in western Europe decades earlier. The gendarme had been the last true heavy horseman there, replaced by cuirassiers, dragoons, and reiters. But the armoured hussars persisted on central and eastern European battlefields. Armor was still viable against Ottoman and Tatar opponents because of their fondness for archery. Nonetheless, all forms of cavalry were in decline as improvements in military technology and tactics continued.

Different as battlefields in the east were, time eventually caught up with the hussars. Infantry were far less vulnerable to cavalry charges with following improvements in firearms technology. Cavalry were unable to press a charge home against disciplined infantry formations. Musketeers had originally been protected by pikemen until their obsolescence. Now musketeers could protect themselves with bayonets and form almost unbreakable square formations against cavalry.

The decline of the hussars in many ways mirrored that of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which was partitioned at the end of the 18th century. For much of the 18th century they were relegated to a ceremonial unit. No longer used in combat, they were used for parades, honor guards, and other duties. They fought their last engagement in 1702 at the Battle of Kliszów where the Swedes defeated a much larger Polish force. Nonetheless, they remain an important part of Polish national consciousness. Commemorated in literature, films, and in song, their legend endures.