In the fertile floodplains between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, human civilization took its first steps. Ancient Mesopotamia, the home of the Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians, has left humanity with numerous inventions, including writing, law, and architecture. But among all these achievements, there was something more primal, physical, and arguably just as universal: wrestling. Considered the world’s oldest sport, the earliest evidence for wrestling is found in Mesopotamia, where it was more than just entertainment. It was part of their identity and culture, and an essential aspect of warrior training.

The Earliest Depictions of Wrestling

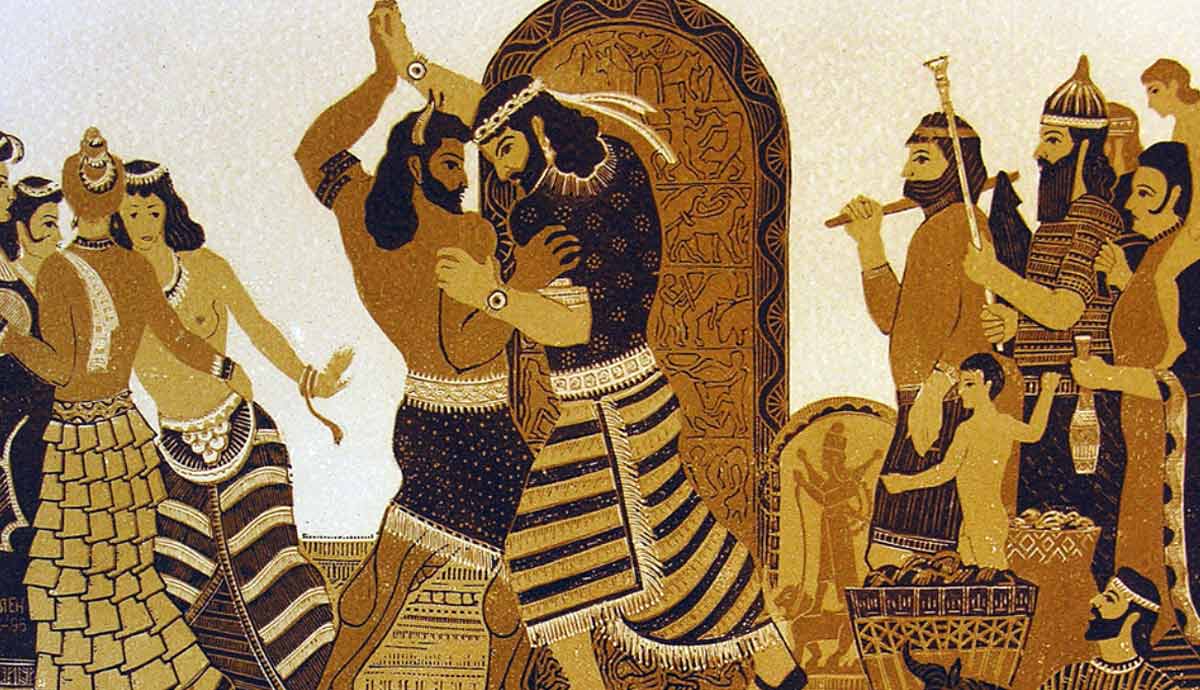

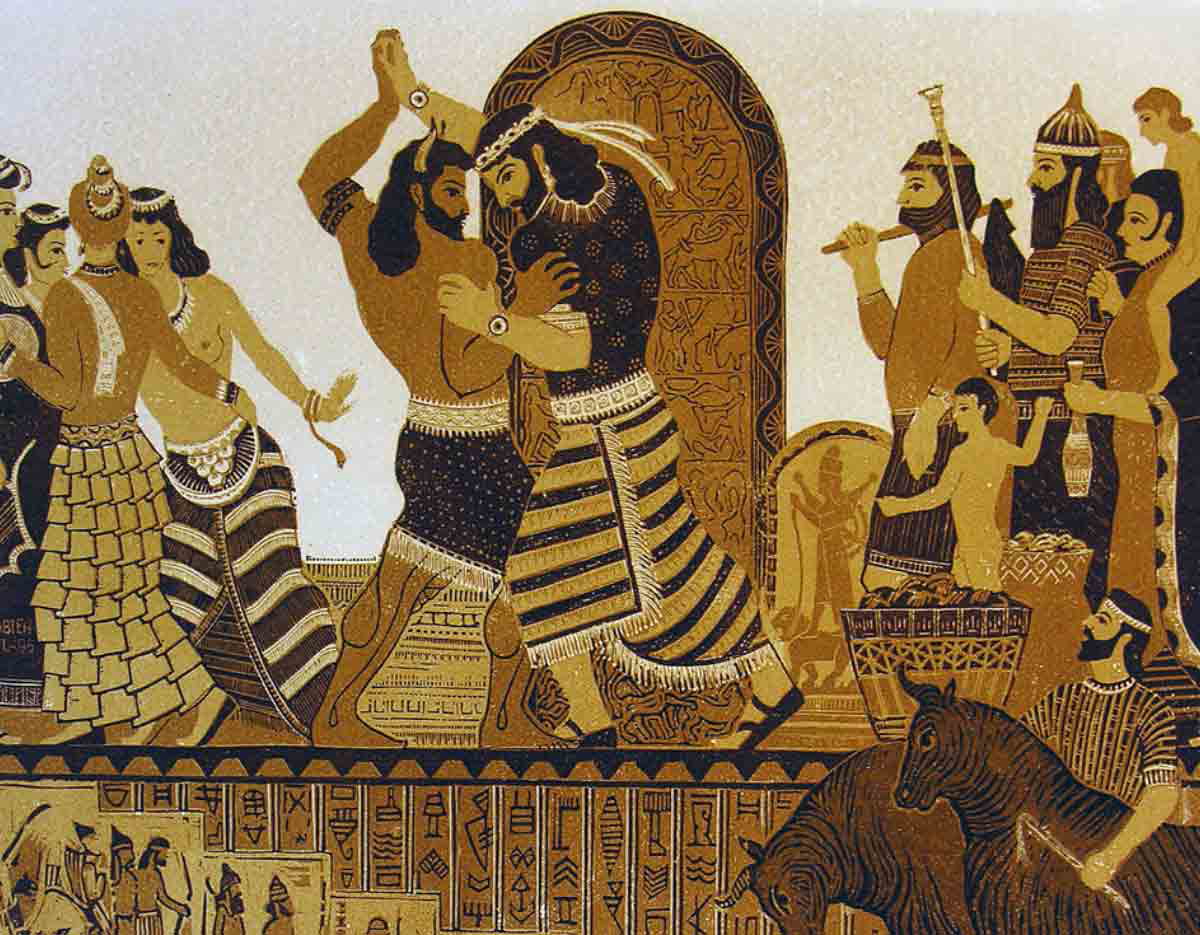

It is mistakenly believed that the Epic of Gilgamesh is the oldest depiction of wrestling in history. Before the Epic, there were several visual representations of this combat sport. In the 20th century, archaeologists discovered terracotta plaques in Mesopotamian cities, such as Khafaji, Kish, and Lagash (modern-day Iraq), depicting men wrestling. This wasn’t just roughhousing; wrestlers are shown in dynamic poses, gripping arms, clinching opponents around the waist, and even lifting them off the ground. Some are completely nude, while others wear only loincloths.

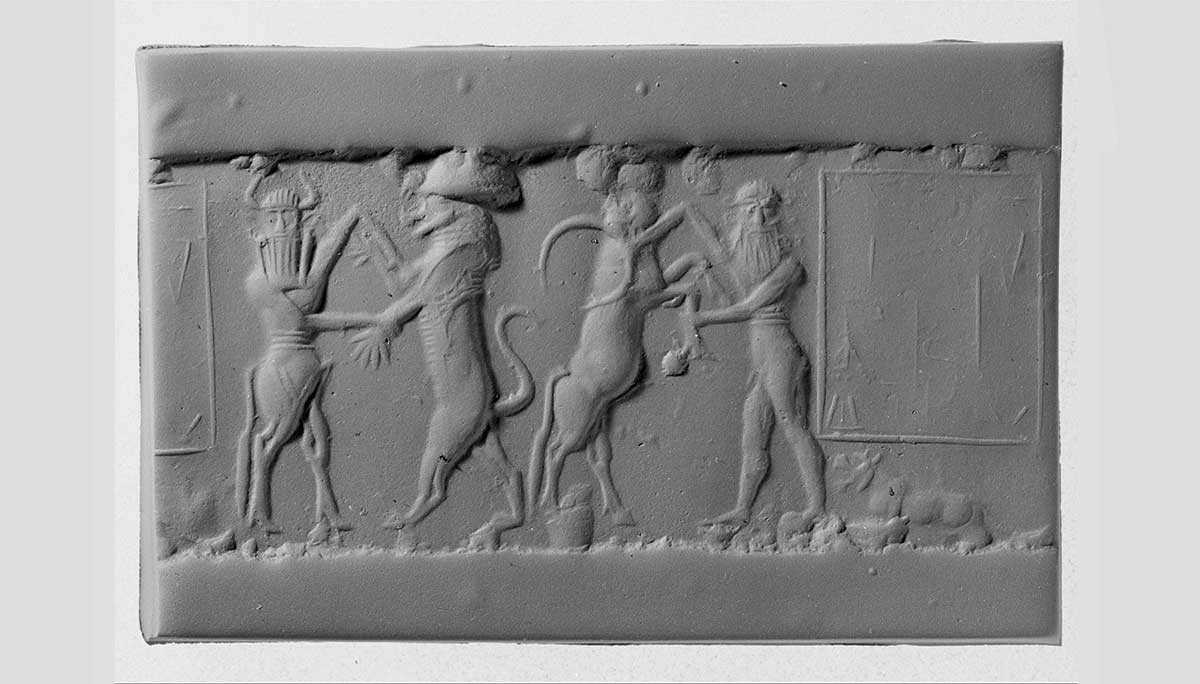

Wrestling also appeared on cylinder seals: small, carved rollers used to press images into wet clay. Some of these seals, especially those from Ur and Lagash, depict wrestlers, often performing in front of an audience or beneath divine symbols. This suggests that wrestling had a ceremonial or even religious role.

What is surprising about all these early depictions is their realistic detail. Historians have noted that many of the poses seen in these artworks closely resemble techniques still used in modern wrestling. This consistency over the centuries shows that wrestling truly has deep roots in human physical expression.

The Epic of Gilgamesh: Wrestling as Myth and Metaphor

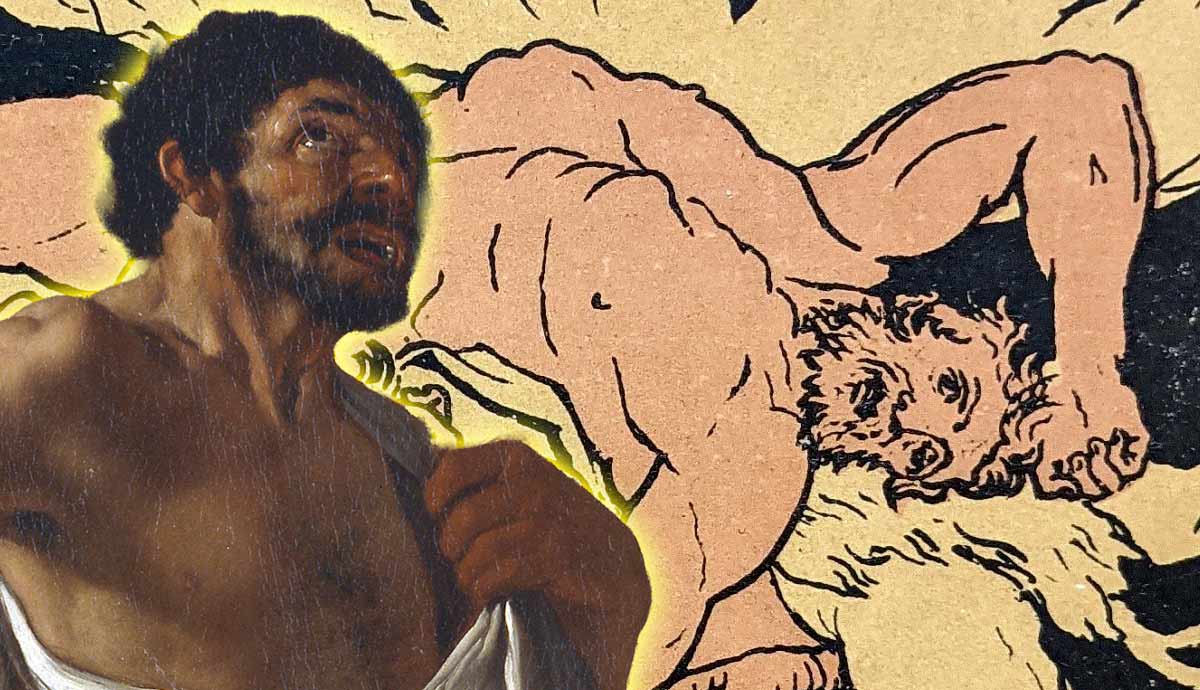

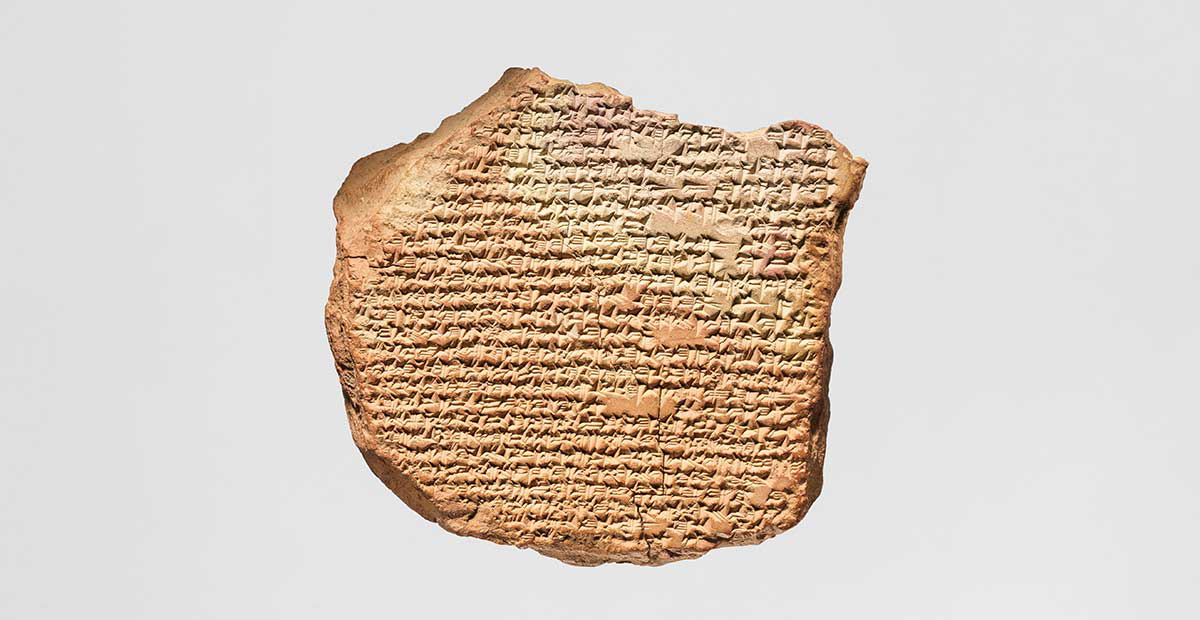

The earliest written traces of wrestling come from the Epic of Gilgamesh, the oldest known epic in history. The Epic of Gilgamesh was written between 2100 and 1200 BCE by a Babylonian writer who called himself Sin-Leqi-Unninni. The epic tells the story of Gilgamesh, the semi-divine king of Uruk, and his wild counterpart Enkidu. Their first encounter includes a powerful and symbolic wrestling duel.

When Enkidu enters Uruk, he challenges Gilgamesh to a duel because of his abuse of power. The two warriors clash in a fierce wrestling match, each trying to overpower the other. Ultimately, neither is truly defeated. Instead, they show mutual respect and become close companions.

“Mighty Gilgamesh came on and Enkidu met him at the gate. He put out his foot and prevented Gilgamesh from entering the house, so they grappled, holding each other like bulls. They broke the doorposts and the walls shook, they snorted like bulls locked together.” (1)

Many believe that this wrestling match is actually a metaphor for inner struggle. Gilgamesh confronts his own arrogance and gains humility, while Enkidu relinquishes his isolation and becomes an integral part of society. In this way, wrestling becomes a symbol of identity, transformation, and balance.

Wrestling in Military Training

Mesopotamian cities such as Sumer, Akkad, Babylon, and Assyria often waged war against each other or against foreign powers. As a result, they placed great importance on physical training. Wrestling in ancient Mesopotamia was not merely a sport; it was a vital part of preparing soldiers for battle. Wrestling shaped recruits into disciplined, agile, and fearless warriors.

Although no formal records of training manuals have survived, we know from art and royal inscriptions that wrestling was part of the royal and military educational system. In Sumerian texts and praise poems, kings often boasted of their strength and compared themselves to wrestlers.

“I am a king treated with respect, good offspring from the womb. I am Lipit-Ectar, the son of Enlil. From the moment I lifted my head like a cedar sapling, I have been a man who possesses strength in athletic pursuits. As a young man I grew very muscular (?). I am a lion in all respects (3 mss. have instead: to the extremes (?)), having no equal.” (A praise poem of Lipit-Eshtar)

However, the clearest examples come from terracotta plaques that depict military life and training. Based on these visual records, it is clear that wrestling played a significant role in the physical training of Mesopotamian soldiers.

Forms of Wrestling in Ancient Mesopotamia

It seems that wrestling in ancient Mesopotamia encompassed a full range of grappling, from upright combat to ground fighting. Many terracotta plaques depict men in standing positions attempting throws, hip swings, or shoulder holds. On the other hand, some scenes continue into ground positions. This may suggest that victory wasn’t declared after the first fall, but that the match continued until one wrestler was completely exhausted or subdued. This hybrid form of wrestling in Mesopotamia resembles modern judo or freestyle wrestling, where transitions between standing and ground combat are fluid and strategic.

There was another form of wrestling in ancient Mesopotamia that probably involved the use of belts or straps. Although no such belts have survived, certain visual depictions suggest that wrestlers grabbed each other near the waist or hips in ways that indicate control through the use of a belt.

Similar wrestling techniques are present in other ancient civilizations such as Greece, Egypt, India, and China. These cultures did not directly inherit wrestling from Mesopotamia; rather, wrestling as a sport developed independently in each, as humans naturally evolve similar grappling strategies in unarmed combat. Therefore, modern wrestling does not descend directly from Mesopotamia, but shares a common DNA: physical human instincts for dominance, control, and skill-based competition.

Wrestling, Ritual, and the Divine

In addition to sporting events, wrestling in ancient Mesopotamia was also present in religious festivals and royal ceremonies held in palaces. Cylinder seals and carved reliefs sometimes depict wrestlers fighting beneath the symbols of deities such as Enlil or Inanna. The symbols of Inanna, the goddess of love, war, and power, were stars, while the symbols of Enlil, the god of air, authority, and kingship, were lightning bolts. Many interpret these depictions of wrestling as symbols of unstable divine energy.

Even the gods of ancient Mesopotamia occasionally engaged in battles that resembled wrestling matches. The most well-known example is the battle between Marduk and Tiamat in the Enuma Elish poem. Marduk was the patron god of Babylon, while Tiamat was the goddess of salt water and chaos. During their battle, Marduk uses a net, a bow, and winds to trap and defeat Tiamat. He then divides her body to form the heavens and the earth. This victory secures Marduk’s place as the supreme deity in Mesopotamian mythology.

“And the gods of the battle cried out for their weapons.

Then advanced Tiamat and Marduk, the counselor of the gods;

To the fight they came on, to the battle they drew nigh.”

The way Marduk defeated Tiamat resembles the technical control of a wrestler, followed by a decisive strike. His triumph is not merely a killing; it is the establishment of cosmic order, akin to a king proving his legitimacy through a ritualistic wrestling victory.

The Wrestler’s Role in Mesopotamian Society

In ancient Mesopotamia, wrestlers enjoyed elevated social status, something like modern celebrities. People from all social classes admired their physical strength and endurance, but their value extended beyond just muscles. Strength in ancient Mesopotamia was a moral, even spiritual, quality. This meant that a wrestler, besides brute force, was expected to have qualities such as strategic thinking and control over their body.

The elevated role of the wrestler in Mesopotamian society is evident in the Epic of Gilgamesh. When the wild man Enkidu arrives in Uruk, he challenges King Gilgamesh to a wrestling match, not only to confront his violent power, but also to prove his worth in the eyes of society.

Wrestling served as a visual metaphor for domination, making it a useful tool in public appearances and propaganda. Kings and rulers often boasted of their wrestling skills in praise poems and inscriptions. Wrestling was seen as legitimate proof of one’s ability to rule, just like military victories or religious devotion.

It is assumed that wrestling was also part of the palace economy and that athletes, like scribes or entertainers, likely had permanent positions at royal courts. They would perform during court events, possibly for dignitaries, visiting merchants, or during treaty festivals.

Wrestlers often blurred roles: half-civilian, half-soldier; half-ritual performer, half-elite athlete. This duality reflects a broader Mesopotamian fascination with figures who cross boundaries.