Europe’s long Middle Ages have a reputation as a low point in Western civilization. The period from the 5th to the 15th century is a byword for anything unenlightened and barbaric. Modern historians, however, prefer to view this stretch as a series of epochs and incremental changes. Among these, the 12th-century Renaissance is especially notable. As a time of intellectual, artistic, political, and economic growth, it illustrates the true dynamism of the Medieval Period and hints at the progress that gradually brought about the more famous Renaissance of a later age.

What Was the 12th Century Renaissance?

The concept of a “12th century Renaissance” was popularized by historian Charles Homer Haskins in his 1927 work The Renaissance of the Twelfth Century. Haskins wanted to fight the perception of medieval western and central Europe as a stagnant society, undergoing little change. Terms like “medieval” and “Middle-Ages” are themselves derived from this attitude, implying a kind of intermission between the greatness of the Roman Empire, which ended in the 5th century, and the Renaissance of the (roughly) 15th century. Haskins highlighted the dynamic growth in scholarship and intellectual output that started in the High Middle Ages.

What brought about this growth? While Haskins focused mostly on the intellectual life of the 12th century, others have tried to fill out the world of that era. Researchers have since written about the economic, demographic, and climatic context of this booming period, giving us clues about its possible causes.

The 12th century in Europe was a time of increased prosperity. In part, this expansion was fueled by climate—12th century Europe was going through a “Medieval Warm Period” which produced good harvests. Farmers also became more innovative, using more efficient methods of plowing, and broadening their system of crop rotation, while exploiting more farmland.

This agricultural surplus fueled an increase in commerce and the growth of population and cities. In 1939, economist William Beveridge published a history of English prices. His work showed that Europe experienced a “price revolution” or trend of inflation starting in the late 1100s. A rising population, with a little more to spend, was creating rising demand for products, inflating their price. As society moved a little further away from subsistence, more people could move to cities and devote themselves to pursuits like scholarship and art.

New Stability

Another contributing factor was increased security and stability. By the 12th century, western Europe’s security situation had changed for the better, enabling peaceful growth. The bloody raids of the Vikings and Magyars had ended. Meanwhile, powerful states and cities were emerging.

For centuries, the Scandinavian Vikings and Eurasian Magyars had launched attacks into Europe from its northern and eastern corners respectively. These raids had supplied the freebooters with pillage, slaves, extortion money, and increasingly, territory. The Magyars struck by land on horseback, while the Vikings came by the waterways. Churches and monasteries, the cultural centers of their day, were often ravaged by both groups, because of their weakness and stores of valuables.

By the 12th century, these raiders had changed their way of life as they were absorbed into mainstream Europe. The Scandinavian peoples formed the kingdoms of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden and gradually accepted Christianity. The Magyars settled down, forming the new Kingdom of Hungary, and likewise converted. These new kingdoms now dealt with the rest of Christendom on a state-to-state basis, rather than through sporadic raids and extortion.

Internally, many European kingdoms became more stable and secure. The 12th century was an era notable for strong, centralizing monarchs. France’s Louis VI (the Fat) forced his wild barons to submit to his authority. His grandson Philip II (Augustus) expanded the power and reach of the French crown, administered justice, and clawed back land from neighbors. England’s Henry II was an accomplished lawgiver and administrator. Meanwhile, the German (Holy Roman) Empire reached a high level of unity and prestige under Frederick I (Barbarossa).

There was also a parallel movement of increasingly powerful and independent cities. Cities across western Europe shook off their feudal lords, and established self-governing communes, loyal only to the king. The most powerful and independent cities blossomed in northern Italy, which had no king.

The consolidation of monarchies and communes helped bring order and administer justice to 12th-century populations. People were now less at the mercy of local nobles and neighborhood bullies. Just like financial prosperity, security and order created a more stable society and a springboard for culture.

Classical Learning and the Rise of the University

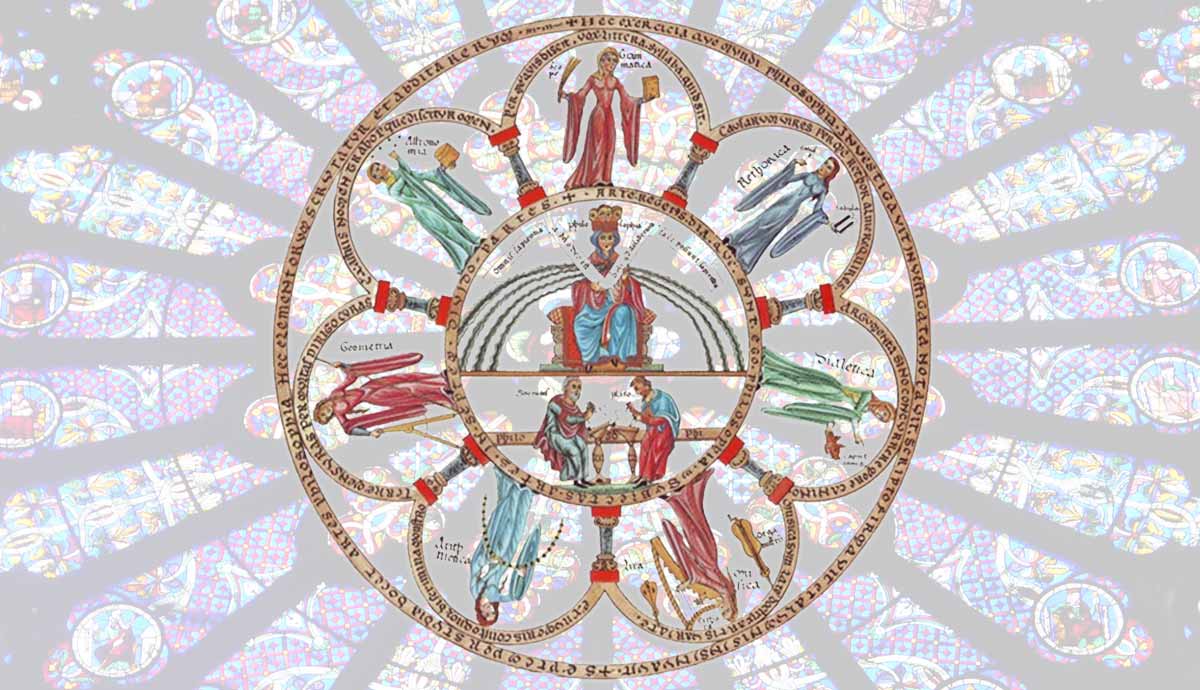

Like the more famous Renaissance of the 15th century, the intellectual revival of the 12th century was rooted in a renewed emphasis on the learning of the Greco-Roman world. The works of Greek writers like Ptolemy, Plato, and Aristotle, and Romans like Ovid, Cicero, and Seneca began to be read more widely, as scholars tried to apply the science and ethics of antiquity to a Christian worldview.

Not all writings were easy to come by. While Western Europeans had long had access to works in Latin, much of the Greek store of knowledge was untranslated and unavailable. In their curiosity to recover the Greek classics, Western Europeans turned to a language even more remote to them—Arabic. Arab writers had translated a large catalog of Greek works into their own tongue. Spain, then mostly under Moorish rule, served as the nearest point of contact between Arabic and Western European culture.

Italian, Scottish, and English scholars, among others, traveled to Moorish Spain and came back with a treasure trove of new translations of the Greeks. They brought back the medical texts of Galen and Hippocrates, Ptolemy’s model of the solar system, the philosophy of Aristotle, as well as much astronomy, astrology, and mathematics.

The way in which knowledge spread also changed in the 12th century. The age saw the development of the first universities in the Western world, the forerunners of all modern universities. Up to that point, medieval learning had been centered around monasteries and cathedral schools. While those institutions still thrived, students also began to flock to the big cities to get instruction from the popular masters of the day.

Groups of students and teachers were incorporated into new academic institutions. By the end of the 12th century universities had formed in Bologna, Paris, Montpellier, Oxford, and Salerno. Cambridge would follow in 1209.

The new centers of learning could specialize in a broad range of topics, including secular (non-religious) subjects. The University of Bologna, in Italy, was the seat of a legal Renaissance. Their scholars made a system of the study of Roman law, which the university helped reintroduce into Europe’s courts. Salerno, specialized in medicine. The University of Paris, meanwhile, became the intellectual center of Western Europe, famous for lectures on theology and philosophy.

While universities took instruction to a broader audience than cathedral schools and monasteries, European intellectual life continued to be wedded to the church. In 12th-century Christian societies, most leading thinkers were clerics. Bernard of Clairvaux, John of Salisbury, and Anselm of Canterbury were all churchmen. Meanwhile, French scholars Peter Abelard and Heloise d’Argenteuil found the church to be their only practical option.

Abelard and Heloise have gone down as the most celebrated couple of their age. Peter Abelard (1079-1142) was a popular teacher who applied classical logic to existential questions of reality, as well as those of church doctrine. Heloise (1098-1164) was one of his students, a learned young noblewoman. The two became lovers yet were separated by Heloise’s family. Abelard became a monk, Heloise a nun and abbess. Both achieved respect and renown as scholars during their lifetime and beyond.

Abelard’s great rival, St. Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153), followed a different path to the church. Bernard was attracted to an ascetic life, joining a Cistercian monastery as a young man. A gifted preacher and writer, Bernard promoted a back-to-basics reform of the church, warning against luxury and vanity—both physical and intellectual. He rejected new ideas like Abelard’s which he saw as heretical. As an intellectual leader, Bernard became more influential than some popes of his day and is considered one of the leading theologians in Christian history.

Abelard and St. Bernard illustrate two strains of 12th-century thought. Abelard wanted to explore knowledge for its own sake, while Bernard wanted to keep Christians grounded in what was important. St. Bernard can be seen either as the archenemy of the 12th-century Renaissance or as a leading contributor to 12th-century thought.

Literature and Song

The revival of law, philosophy, and the sciences were not the only fruits of this Renaissance. As literacy spread, songs and poems multiplied. Entertainment flourished in the troubadour tradition of what is now southern France.

William IX, Duke of Aquitaine (1071-1126), a knight, and poet, helped popularize this art form. William composed and sang poems of courtly love in the Occitan language. Many southern noblemen followed his lead. Courtly love was the wooing of (usually married) noblewomen by knights, who had to prove themselves worthy through patience and growth of character. Troubadour themes could also cover topics like politics and morality.

William IX’s granddaughter, Eleanor of Aquitaine (1122-1204), was a patron of the troubadour’s art. After Eleanor married England’s Henry II, she helped to spread southern culture to Henry’s northern French dominions. Trouveres sprang up as the northern equivalent of troubadours. Eleanor’s daughter from her first marriage, Marie of France, became Countess of Champagne, and from her northern fief became a great patron of music and literature in her own right.

Literature as entertainment made a strong comeback at this time, notably in the form of Arthurian romances. Stories of King Arthur and the knights of his round table, of Merlin the magician, of Queen Guinevere, and of Parzival’s quest for the holy grail, stem from the 12th century more than any other.

British churchman Geoffrey of Monmouth (1095-1155) picked up scraps from 6-7th century Welsh poetry about Arthur, a brave British warrior who resisted Saxon invaders. Arthur stands on a shaky historical foundation, no one knows if he even existed. Geoffrey, however, started to flesh out a world for King Arthur, introducing new characters and writing extensively on Merlin’s prophecies.

In the late 12th century, Chretien De Troyes, a French writer patronized by Marie of France picked up where Geoffrey left off. Chretien introduced Lancelot, the holy grail, and other classic Arthurian tropes. While set in the 6th century, Chretien’s Arthurian world reflected 12th-century views of chivalry and politics.

Art and Architecture

The 12th century also saw the beginning of new trends in architecture and the visual arts. As in academia, members of the clergy drove much of this growth. With enormous resources, ambitious churchmen hired craftsmen to construct beautiful, elaborate new creations, allowing them to express themselves while exalting God.

Abbot Suger’s (c. 1081-1151) rebuilding of the Basilica of St. Denis popularized a bold new style of architecture later labeled as “Gothic.” Suger’s basilica was built to be unusually tall and spacious, with many windows to bathe the interior in light.

A few key architectural techniques became the cornerstones of the new Gothic style. Flying buttresses were used on the upper exterior. These arches helped to relieve the building of some of the pressure of its weight. In the interior, rib vaults, a group of very tall arches or “arched ribs,” intersected to form a ceiling. Pointed arches, which could support more weight, were used indoors, as vaults, and decorative features.

The famous Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris was begun in the late 12th century along Gothic lines, as was the magnificent Cathedral at Chartres in northern France. In the following century, England would build Canterbury Cathedral and an updated version of Westminster Abbey in Gothic style.

Another French innovation was Gothic sculpture and later painting. Human figures now assumed more realistic shapes, while their faces showed a richer range of emotions. The stained glass in Gothic churches depicted realistic human forms in a highly ornate and colorful setting.

Romanesque painting and sculpture, meanwhile, were more expressive and could be less realistic. This style was strongest in southern Europe and was inspired by Roman and Byzantine art. Romanesque paintings were an elaborate mix of human shapes and decorative patterns, designed to convey a message—often religious—to their audience.

Bibliography:

The Applied History Research Group/ University of Calgary. (1997) The End of Europe’s Middle Ages, The End of Europe’s Middle Ages – Economy (umb.edu)

Bradbury, J. Philip Augustus King of France 1180-1223. The Medieval World. Routledge.

Broedel, H.P. (2017) History of Applied Science and Technology. Chapter 5- The Rise of Universities and the Discovery of Aristotle. Chapter 5 – The Rise of Universities and the Discovery of Aristotle – History of Applied Science & Technology (rebus.community)

Burns, J.H Ed. (1988) The Cambridge History of Medieval Political Thought c.350-c.1450. Cambridge University Press.

Chavas, J.P, Bromley, D.W. (2005) Modeling Population and Resource Scarcity in Fourteenth-century England. Journal of Agricultural Economics/ Volume 56, Issue 2/ p. 217-237.

Fischer, D.H (1996) The Great Wave. Oxford University Press.

The Gothic style-an introduction. Victoria and Albert Museum.

The Gothic style – an introduction · V&A (vam.ac.uk)

Hammer, J. (September, 2022) Was King Arthur a Real Person? Smithsonian Magazine.

Was King Arthur a Real Person? | Smithsonian (smithsonianmag.com)

Haskins, C.H (1955) The Renaissance of the Twelfth Century. Harvard University Press. Work originally published 1927.

James, E. (2011, Mar.9) BBC. History – Overview: The Vikings, 800 to 1066. https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/vikings/overview_vikings_01.shtml

King, P. and Arlig A. (2022, August 12) Peter Abelard, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/abelard/

Ozment, S. (August 18, 2020) The High Middle Ages – Yale University Press

Somerville, A. and McDonald, R. (2013) The Vikings and their Age. University of Toronto Press.

Swanson, R. (1999) The Twelfth-Century Renaissance. Manchester University Press.

Thorndike, L. (1917) The History of Medieval Europe. Houghton Mifflin.

Winiarski, M.V.R (2017) The Troubadours, About Troubadours.