Adam Smith is commonly associated with The Wealth of Nations and his impact on economics. But this groundbreaking thinker didn’t start out by studying how capitalism works—he also wrote about morality. His book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, offers deep insights into human nature and ethics. In this work, there’s a discussion on why we care what other people think or how fairness influences our judgments. Adam Smith was interested in a lot more than just money and trade. So, let us explore some ideas from Adam Smith’s moral philosophy.

Sympathy as the Foundation of Morality

In his work The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Adam Smith posited that when we make moral judgments, our feelings of compassion take center stage. By sympathy, Smith didn’t just mean feeling sorry for someone. He meant imagining what it would be like to be in another person’s shoes.

This capacity for identifying with others is key to our ability to connect with them emotionally. And this connection guides our moral decisions.

If you see someone stumble and fall, you will probably cringe. You may even feel as though you have taken a tumble yourself. Smith says this discomfort—sympathy again—isn’t confined to those we love or know well. We experience it for all humans and even animals.

If one witnesses an individual experiencing unjust treatment, their capacity to empathize with that person’s pain leads them to view this treatment as unfair. They may then be moved to take action—or at least form an opinion—based on what they believe is a moral perception of injustice.

An easy-to-understand illustration of Smith’s idea can be found in acts of charity. Even though we may not be hungry or needy, seeing others undergo these hardships moves us to give assistance. It inspires help from us.

For Smith, this ability to feel for others lies at the root of our sense of right and wrong. It helps explain how we can get along (most of the time) in communities where everyone’s needs count just as much as our own. Morality, in his view, is thoroughly human because it rests on empathy of this sort.

The Impartial Spectator

Adam Smith brilliantly believed in the “impartial spectator.” This is one of his coolest ideas. It’s all about how people decide what’s morally okay and what isn’t.

Smith says we’ve all got this inner voice. It watches us from inside our heads (figuratively speaking). The voice helps us work out right from wrong. It points at things we do or want to do and either says “Good!” or “Nope!” as if it were judging a contest.

Say you made a promise but now wish you hadn’t: maybe you feel keeping it isn’t in your own best interests. What would someone totally fair and square, with no axe to grind either way, think if they knew about the promise and saw you thinking of breaking it?

This point of view encourages consideration along the lines of “If I do this, what will people think?” It’s not only wanting to avoid feeling guilty or being criticized by others—it’s also about behaving in ways that fit with a sense of right and wrong that goes beyond a single person’s perspective.

For example, imagine someone seeing a wallet containing lots of money fall out of a bag. At first, they may be tempted to take it, but then their inner fair-minded voice speaks up and reminds them: “But wouldn’t an honest individual hand the cash over?”

By picturing how someone unbiased might respond, the individual is guided toward choosing what is morally correct. This internal referee doesn’t just stop individuals from acting on every selfish urge. It helps them behave in ways that match up with wider social expectations and principles of good conduct.

Self-Interest and Benevolence: A Moral Balance

Adam Smith is often associated with promoting self-interest in The Wealth of Nations, but his understanding of human nature is much more complicated. In The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith suggests that selfishness and kindness are not opposites.

Rather, they can go hand in hand in an intricate moral dance. People, he thought, are selfish creatures, yet also have a natural impulse to care for others.

For instance, think about people who run businesses. It may seem clear enough that they are trying to turn a profit. This is what Smith means by self-interest. But does it follow that such individuals are devoid of benevolence? On the contrary, many successful entrepreneurs give back to their communities in various ways.

Smith would argue that having both self-interest and benevolence leads to a balanced moral character. A business owner needs to be self-interested to do well, but they also need to care about others if they are going to contribute to society.

Purely looking after yourself can make you greedy. Caring for others too much can mean you don’t look after yourself and become vulnerable. Smith thought being moral meant navigating between these extremes.

When you are negotiating your pay, it is fair to want as much money as possible—that’s in your own self-interest. But being moral also means spare a thought for your employer who doesn’t have unlimited funds (benevolence).

The Role of Society in Shaping Moral Sentiments

Adam Smith posited that society has a significant impact on the formation of our moral beliefs. He rejected the notion that humans are born already knowing what is right and wrong.

Smith argued that our moral values arise from our interactions with others and from social conventions. It is in these social settings that we learn to be empathetic, to understand prevailing attitudes about proper behavior, and to shape our own conduct accordingly if we wish to be praised rather than blamed.

To illustrate, a child begins to grasp the idea of fairness. At first, the child may not see why it is so great to share things. But after watching kids being nice to each other (and getting lots of smiles from grown-ups when they do likewise), that same child eventually realizes there must be something pretty neat about this sharing stuff after all.

Smith suggests that what motivates us as we grow up is not just wanting everybody to think we’re cool guys for following rules but also needing them to approve of us.

Consider how society’s attitudes towards topics such as fairness or taking care of the planet have altered over time. As social expectations change, individuals change their conduct, too, not only for personal reasons (such as wanting to help the environment) but also because they want to fit in with what everyone else considers morally right.

If Smith is right, then this social pressure is important because if it disappeared, people would no longer get the outside prompts needed to fine-tune their moral feelings.

Society’s rules profoundly shape our ways of behaving well (which may include helping others even when it costs us), and following them can improve collective life.

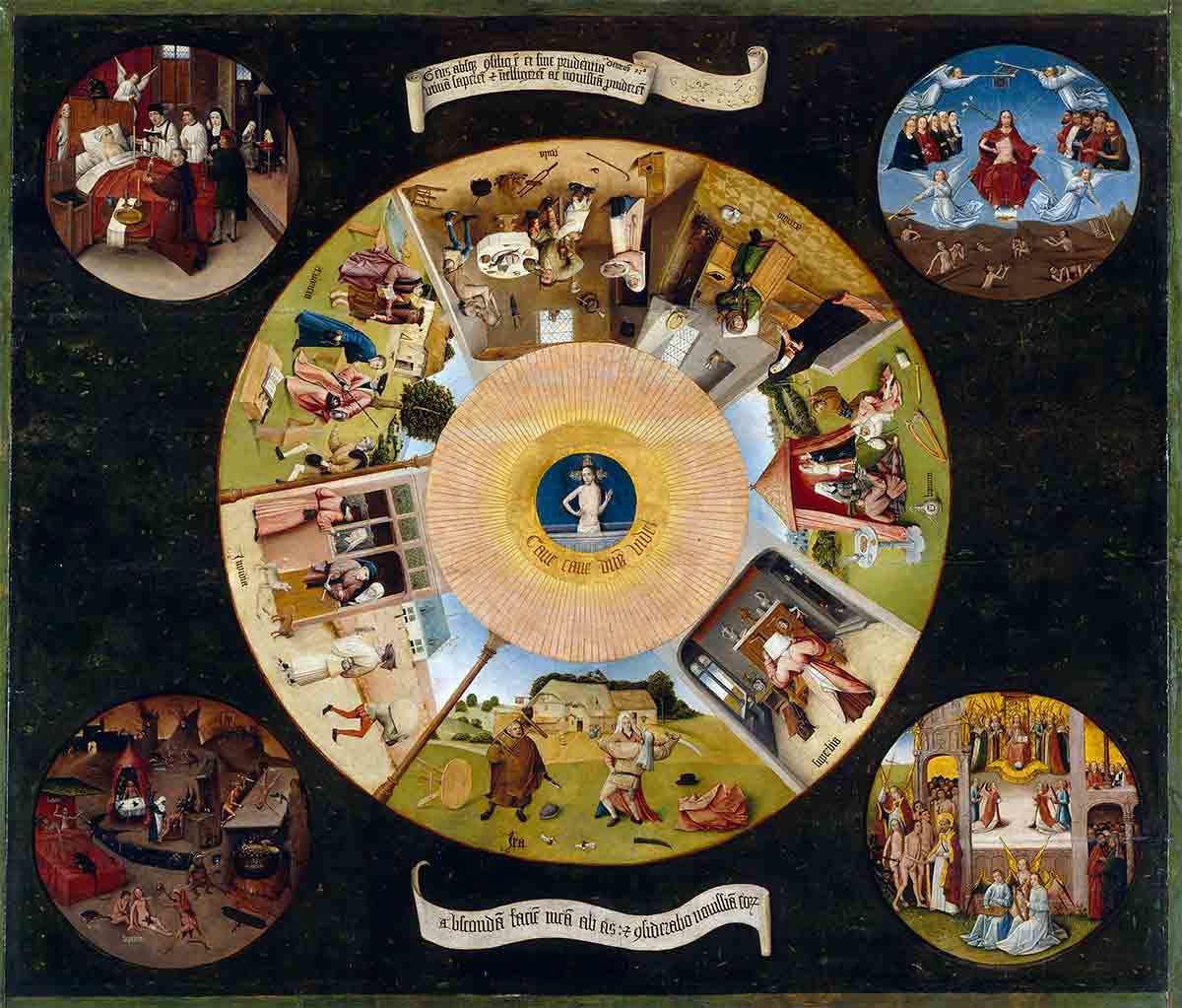

Justice as the Pillar of Society

Justice was paramount for Adam Smith when considering what makes a society work. In The Theory of Moral Sentiments, he said societies fall apart without it and become chaotic rather than functional.

For individuals living in a community without justice, there is little point in having laws or rules because there is nothing to make sure people treat each other fairly (or don’t hurt one another). It is up to everybody to be nice, not just not hurting others.

He uses the example of theft: if thieves are never punished, then everyone will always be worried about their stuff being stolen. Or maybe someone hurts you, but there’s no penalty. How could you ever trust that person again? You couldn’t, so there’d be lots of things like friendships that were impossible, too.

Smith believed that human beings have a natural feeling for justice, which develops out of relationships with other people.

An intriguing instance is the way companies work inside a fair legal system. Firms use agreements. They understand that if somebody doesn’t keep their side of the bargain, the law will help them out.

This faith in fairness helps economic growth: Businesses can expand, trade increases and individuals can cooperate for everyone’s benefit.

Smith also said justice rests on two things people want very much. One is duty, which means following rules because they are right. The other is approval: we like it when others think we are behaving well.

But fairness does more than allow people to punish wrongdoers or get along with each other—it does these things and also helps maintain an underlying order.

Moral Sentiments and Economic Behavior

Smith thought economics and ethics were closely linked. While most people see The Wealth of Nations as a book that explains how capitalism works, its moral ideas are found in his earlier work, The Theory of Moral Sentiments.

In these books, Smith suggests that economic activity—such as buying things or making a profit—is not only driven by self-interest. It also comes from a “moral sentiment,” meaning a feeling such as guilt, fairness, duty, empathy, or concern for others.

For example, Smith writes about a shopkeeper who sells goods in a market town. Of course, the shopkeeper wants to make as much money as possible (this is their “self-interest”).

But this does not in itself explain why the individual opens the shop door every morning in order to do business. In addition to the desire for wealth, there must be other sentiments or feelings at work if we are to understand such behavior.

Smith argued that moral feelings play a role in tempering the purely mechanical forces of markets (such as the laws of supply and demand) within capitalism. One reason he believed this is that such emotions can help build trust, which is often hard to come by when there’s little more than competition.

If employees have confidence that their employer won’t try to cheat them (but instead will pay fair wages), these workers may feel better about their jobs. They might even work harder, something else that makes sense from an economic viewpoint.

So, What Are Adam Smith’s Moral Sentiments?

The Theory of Moral Sentiments is a less-read book from Adam Smith’s writings. This book presents another kind of economist that is different from what is commonly recognized.

In a nutshell, Smith’s moral philosophy allows humans to possess an inherent capability for sympathy in feeling others’ emotions. It is also partly due to society.

A person’s values are created by the customs he grows up with and wants to fit in with. Justice is also important because it makes society work smoothly. When people are just and reliable, others respond in kind.

These moral sentiments also counterpoise against the mechanistic side of capitalism. They are a reminder that humans are not just out for themselves.

This book suggests that fairness, justice, and compassion must be balanced when deciding how we want economic and social systems to look.