For a long period of American history, art created by African Americans was considered irrelevant and unworthy of appreciation. Still, even in the conditions of slavery, segregation, and oppression, African American creatives managed to build and preserve artistic tradition. Some of them managed to become part of the major art scene despite all obstacles. Read on to learn more about the earliest known African American artists and their impact on the history of art.

African Americans in Art: A Complex Journey Towards Creative Expression

The generational trauma of slavery and racial discrimination defined many aspects of art made by African American creatives. For generations of African Americans, professional art education or even conventional art practice were unavailable. Enslaved people nonetheless had their own forms of art that were rarely deemed as significant by the dominating white class. African American artists created pottery, quilts, carved wood objects, musical instruments, and many more. Skilled enslaved artisans occasionally were allowed to accept commissions from outside their household, earning money for personal use.

Still, the majority of the American public questioned the mere capability of African Americans to create art. In an article published in the New York Herald in 1867, the author noted the substantial presence of African Americans on art exhibitions and commented that they seemed to have “an appreciation for art while being manifestly unable to produce it.” This article angered landscape painter Edward Mitchell Bannister so much that he decided to develop his skills out of pure spite.

Still, despite oppression and social obstacles, African American artists successfully conquered artistic space for self-reflection and expression. The Harlem Renaissance movement revealed hundreds of African American talents who created works relevant not only for their community, but for art history as a whole. Today, contemporary African American artists still get inspired and pay tributes to those who were the first to fight for recognition and appreciation of their artistic visions.

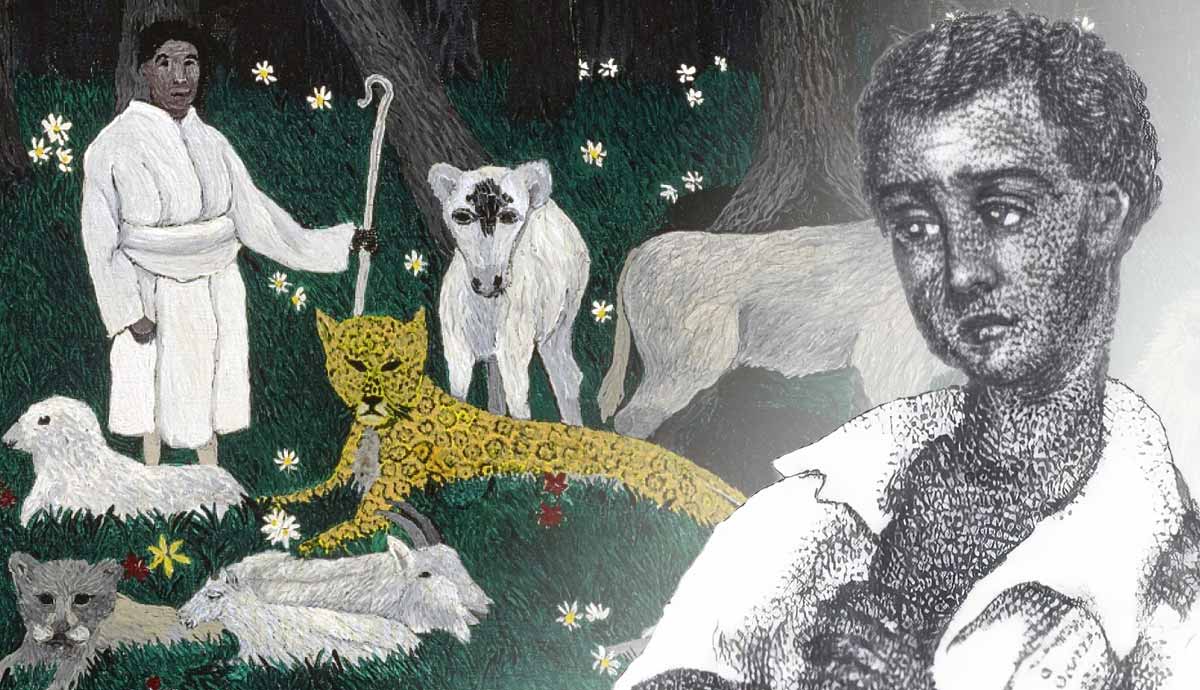

Joshua Johnson (1763–unknown): The First Known African American Painter

Joshua Johnson is the earliest known African American artist to launch a professional career. The details of his biography remain vague, as his story was forgotten for more than a century. Generally, art historians agree that he was a son of an enslaved woman and a white man who bought the child from a Baltimore farmer. George Johnson officially acknowledged Joshua as his son and granted him freedom. Unfortunately, the fate of the boy’s mother remains unknown and, most likely, was unaffected by her son’s change of status.

In various state documents Johnson was registered as a portrait painter, and claimed he was entirely self-taught. His style was fairly similar to portraits by the Peale family of artists, trained by the famous painter Charles Wilson Peale. Johnson’s capabilities as a painter were rather limited, as he used a limited set of poses, angles, and decorations for each known work. Stylistically, his work was similar to the primitivist works of Henri Rousseau created in the early 1900s. Still, documents suggest he was a financially successful artist in considerable demand. Johnson’s story is a remarkable case of a Black artist’s suсcess in the face of discrimination.

Patrick Henry Reason (1816–1898)

Patrick Henry Reason was one of the earliest known African American printmakers and an abolitionist. Although he had Haitian origins, he was born in New York and attended a pro-abolition African Free School founded by John Jay and Alexander Hamilton. His artistic talent became obvious in childhood, and he was an apprentice to a well-known lithographer.

In his twenties, Reason established his own engraving and print shop. Aside from private commissions, Reason’s main focuses of work were illustrations for abolitionist publications and portraits of activists like Henry Bibb, the formerly enslaved man who escaped to Canada and helped countless others to break free through the Underground Railroad.

Edward Mitchell Bannister (1828–1901)

Unfairly forgotten today, Edward Mitchell Bannister was an accomplished and popular landscape painter. He lost both of his parents early, and was placed to live with a well-off white farmer’s family. There, he first demonstrated an interest in art and began copying artworks that he saw in his foster family’s home.

Unlike some other successful Black artists of his time, Bannister never traveled to Europe but nonetheless was greatly inspired by French art. His main artistic influence came from the Barbizon School, a semi-Realist art movement that focused on true-to-life depictions of local nature and rural life. The issue of studying local landscapes was crucial for the Barbizon painters who worked in villages and forests around Paris. Bannister applied this concept to American nature and mostly painted in Rhode Island.

Harriet Powers (1834–1910)

Unfortunately, history did not preserve the names nor the works of countless African American artists who were born into slavery. Harriet Powers is a happy exception. She was an enslaved seamstress who became famous for her complex quilts that retold stories from the Bible. Sewing was an essential skill for any woman at the time, especially an enslaved one, yet Powers was a trained professional who worked on a sewing machine and was in high demand.

After her emancipation, she supported herself through sewing and demonstrated her storytelling quilts on fairs. Quiltmaking was a popular artistic form among African American women at the time, but most works relied on geometric patterns or simple compositions rather than multi-panel narratives from Powers’ work.

Edmonia Lewis (1844–1907)

Edmonia Lewis was a true prodigy whose success happened despite great odds and thanks to a great amount of luck on her and her family’s side. She lost both of her parents as a child, and was left with her aunts who belonged to the Ojibwe people, while her older brother tried his hand at the California Gold Rush. Surprisingly, he managed to find gold and earn a significant amount of money which transformed Edmonia’s life. She was now able to study (although she did not finish college due to racist pressure and false accusations) and travel to Rome, following her interest in art.

Lewis adopted the Neoclassical style of Italian sculpture and used it to create sculptural compositions representing African Americans and Indigenous American people. The unusual interaction between the style and the subject matter, accompanied by the outstanding quality of her work, soon made Lewis an international star and her studio, a popular tourist spot.

Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859–1937)

Henry Ossawa Tanner was the first African American artist to achieve international success. His mother was a former slave who escaped through the Underground Railroad, and his father, a born-free Methodist bishop. The religious upbringing marked Tanner’s professional life, as he became famous mostly for painting religious scenes. Initially, Tanner studied art in Philadelphia. He was the only student of color in his group and experienced discrimination on every step of his career. Eager to move to a less hostile environment, Tanner traveled to Europe and soon settled in Paris where he achieved success.

In Paris, Tanner studied in the famous Académie Julian, a private art school that became known for training the most progressive and original artists of the 20th century. In France, the artist quickly became accustomed to the local artistic community and began receiving commissions. Unable to fight racial prejudice on his own, he chose to stay in Paris for the rest of his life.

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller (1877–1968)

Another prominent African American sculptor, Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller was born into an affluent Black family of beauticians and salon owners. Her parents had many upper-class white clients, which provided them with substantial income and opportunities unavailable to most. This allowed Fuller to obtain quality education and follow her early interest in art by going to Paris. There, she was mentored by Henry Tanner and Auguste Rodin, who noted her talent and unique style.

Fuller’s sculptures were based on her childhood interest in horror stories and on her contemporary Symbolist aesthetic. Nonetheless, she frequently referred to African and African American culture and the reality of discrimination and violence, and the collective trauma of slavery. Like Edmonia Lewis, Fuller became one of the most successful African American women artists in history.