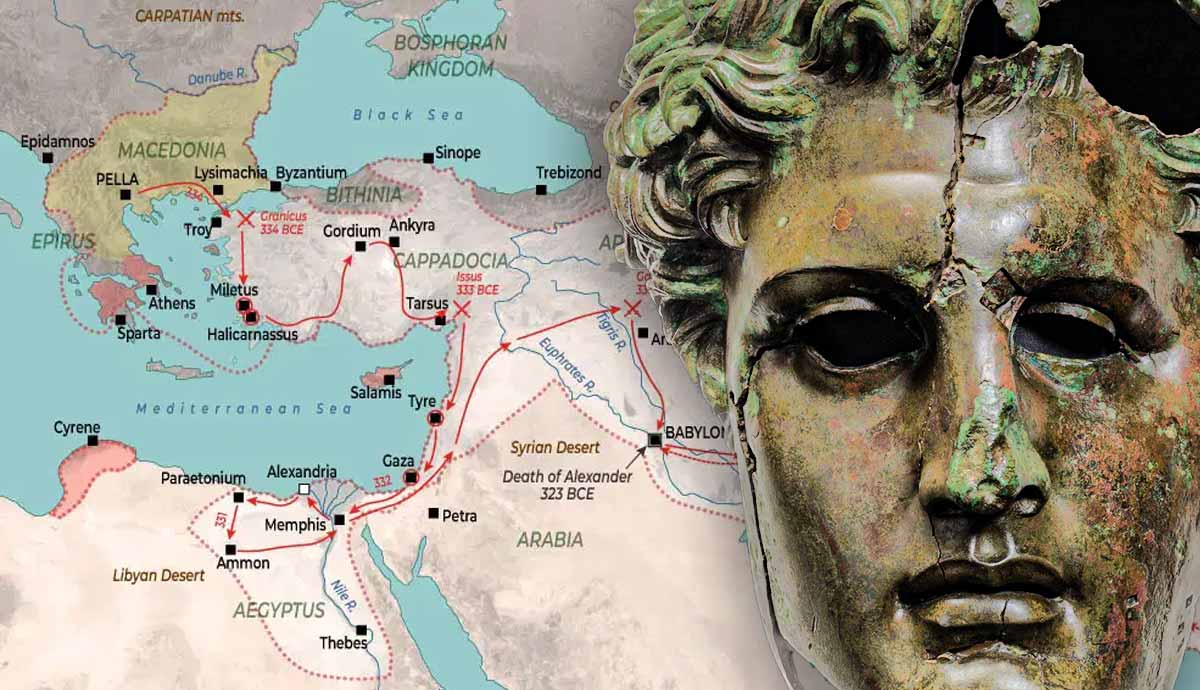

Alexander the Great’s conquest of Anatolia brought him to the city of Gordium in the land of Phrygia. By this point, Alexander’s prowess as a general and conqueror was well known. He was challenged or invited by the priests and leaders to attempt to untangle the Gordian knot. This complex knot was tied around the yoke of a Phrygian oxcart or chariot and had a history stretching back centuries. It was an object of political and religious significance, as it was believed that only the one destined to rule all of Asia could untangle it.

The Legend of the Gordian Knot

The Phrygians were an Indo-European people who settled in Western Anatolia at the end of the Bronze Age. They appear to have originated in the Balkans and moved into Anatolia when the Hittite empire collapsed. The Phrygians were powerful enough to maintain a separate cultural identity and interacted with both the Greeks and Assyrians. In the late 8th and early 7th centuries, the Phrygians were subjected to a series of raids by the nomadic Cimmerians. These attacks culminated in the destruction of Gordium in c.696 BCE and the suicide of the Phrygian king. Minor Phrygian kingdoms continued on until they were absorbed by the Lydians and Medes in the 6th century. When the Persian King Cyrus conquered Lydia in 546 BCE, Phrygia became part of the Achaemenid Empire.

According to the accounts written down by ancient historians, the Gordian Knot dated back to the early days of the Phrygian kingdom. At that time, there was no king so an oracle was sought to help decide who would rule the Phrygians. The oracle stated that the next man to enter Gordium on an oxcart would become king. Soon, a peasant named Gordias entered the city and was crowned. In gratitude, Gordias’ son Midas, an important mythological figure best known for his “golden touch,” dedicated the cart to the Phrygian god Sabazios (Greek Zeus/Dionysus). The cart was bound with an intricate knot, and eventually, an oracle appeared stating that whoever could untangle the knot would rule all of Asia.

Modern Interpretations

There have been numerous attempts to interpret the meaning of this story or myth. Untangling the Anatolian, Phrygian, Greek, and Macedonian cultural elements has proven to be quite challenging. At its core, the myth serves to legitimize the rule of the local Phrygian dynasty. The myth suggests that the ruling dynasty was not an ancient one, but one with widely remembered local roots. It is also possible that this dynasty was founded by outsiders, as the ox cart suggests a longer journey to the city. The prominent position of the oracles in the story is also important. They likely indicate that this was a dynasty of priest-kings allied to an oracular deity. Others have suggested that the Gordian Knot was in fact a cipher that symbolized the ineffable name of a god that was only ever revealed to the priest-king.

Such foundational myths were quite common among the ruling dynasties of the Ancient Near East. Usually, they involved some sort of conquest or the slaying of a monster, so this one is rather unique in that regard. It has been suggested that the Gordian Knot was in some way connected to a myth in Macedonia of which Alexander was aware. Perhaps, the Greeks associated it with the god Dionysus. According to Greek myth, Dionysus had wandered the earth at the head of a large army. His wanderings were more of a military conquest, and he was said to have reached Asia. It is also worth noting that Dionysus was the god who bestowed on Midas the famous “golden touch.”

Alexander’s Solution

The ancient sources agree that Alexander the Great was challenged to untangle the knot when he arrived at Gordium. They do not agree on the nature of Alexander’s solution. The story is related by Arrian, Plutarch, Qunitus Curtius, Aelian, and by Justin in his epitome of Pompeius Trogus. In the most popular version of the story, when Alexander is confronted by the Gordian Knot, he draws his sword and slices through it in a single, decisive strike. It is a dramatic scene, with a sudden burst of decisive action. It also fits with Alexander’s personality and foreshadows the manner in which he would come to rule over all of Asia. In a slightly different version of the story, Alexander first attempted to untie the knot but failed. He then decides that it does not matter how the knot is untied and slices it apart with his sword.

There is an alternative version of the story, related by Arrian and Plutarch, that some modern scholars view as the more plausible. In this version, Alexander does not resort to his sword in order to undo the Gordian Knot. Instead, he focuses his attention on the carriage itself. He solves the challenge by removing the linchpin from the pole to which the yoke of the oxcart was fastened. This allows him to move the pole and the yoke out of the way exposing the two ends of the Gordian Knot. Alexander then simply unties the knot without having to resort to his sword. Here, Alexander’s wisdom and cleverness are highlighted, and his actions have an air of divine intervention about them.

Legacy

After solving the challenge of the Gordian Knot, Alexander went on to rule over much of Asia. While he did not rule over all of it, he did rule over just about all of what was understood to be Asia in Antiquity by those living in the Mediterranean. The manner in which he did so was accomplished through equal parts brutality and clever thinking. For those living in the Ancient Near East the oracles attached to the Gordian Knot were fulfilled in a spectacular and very literal fashion.

Alexander’s solution to the challenge of the Gordian knot became a favorite theme of storytellers and artists even in the modern era. Today, the Gordian Knot has become a metaphor. Any seemingly intractable problem that is solved through an unexpectedly direct, novel, rule-bending, decisive, and simple approach that removes the expected constraints is often referred to as a “Gordian Knot.” So widely known was the story and so powerful is the metaphor that it was even used by William Shakespeare in Henry V, another story of a great conqueror overcoming great odds. Hopefully, the story of Alexander the Great and the Gordian knot will continue to serve as an inspiration for all those faced with seemingly intractable problems. Sometimes, the solution is simpler than it seems.