Before the ancient Egyptians built pyramids to house their god-kings for eternity, they built less enduring and less aesthetically pleasing tomb structures known as mastabas. Taken from the modern Arabic word for “bench,” mastabas were flat, raised mud-brick structures that housed the kings’ tombs underneath. Despite their rather unassuming look, mastabas played an important role in the development of ancient Egyptian religion and culture. Mastabas would become the literal and figurative building blocks for pyramids, giving Egyptian engineers inspiration for their later, more imposing structures. Mastabas would also influence Egyptian religion.

Before the Mastaba: The First Mound Temple

While mastabas were precursors to the pyramids, precursors to mastaba construction began in one of ancient Egypt’s first cities, Nekhen, more commonly known by its Greek name, Hierakonpolis. Located in the far southern part of Egypt, known as Upper Egypt, along the Nile River, Hierakonpolis formed as several villages coalesced in about 2900 BCE. Hierakonpolis was an important city in the Predynastic and Early Dynastic periods, serving as a political and religious center. One of the most significant archaeological finds from Hierakonpolis was the Narmer Palette, which is believed to represent the political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt.

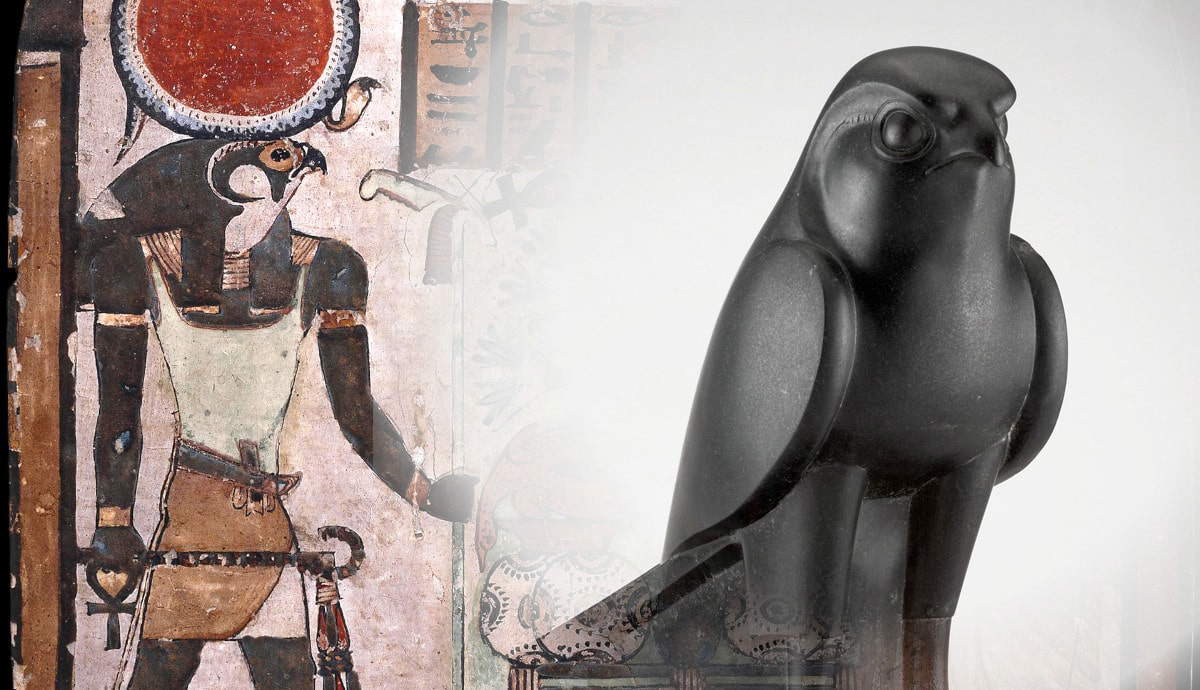

The religious significance of Hierakonpolis was centered around its being a cult center of Horus, the falcon-headed Egyptian god of the sky and kingship. Egyptian kings were believed to be the living incarnation of Horus, with the god playing an integral part in Egyptian religion throughout pharaonic history.

Horus may have been the theological focal point of Hierakonpolis, but the archaeological center was a large temple mound. Little is left of the temple mound because it was built from mudbrick, which does not preserve well over the millennia. Nevertheless, the mound was quite large, as determined by a 162 feet long retaining wall that enclosed it. Although the Hierakonpolis temple apparently did not function as a tomb, it likely became a template for later mastabas.

The idea of a mound played an important role in Egyptian theology. Mastabas were likely meant to resemble mounds, as were later pyramids. But what those mounds represented is open to scholarly interpretation. Perhaps the most credible theory suggested by Egyptologists is that mastabas, and later pyramids, represented the primordial mound of creation. According to the Heliopolitan version of creation, the creator god, Atum, came forth from the primeval mound in an act of self-creation. Atum then created the first pair of deities, Shu and Tefnut, through masturbation, as related in the ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts. The text also impeaches Shu and Tefnut to place the king between them and “set the King among the gods in front of the Field of offerings.”

Therefore, it is likely that mastabas represented where the Egyptians believed life began. The Egyptians also believed that when the king died, he returned to that place so that he could live again for eternity.

Abydos: The City of Mastabas

Located north of Hierakonpolis but still in Upper Egypt, Abydos was an important cult center. The significance of Abydos was linked to its association as the home of Osiris, god of the dead, so temples were built for the god throughout Pharaonic history. Sitting on the west bank of the Nile River, Abydos set the precedent for the proper side of the Nile for tomb construction. All the kings of the First Dynasty and the last two kings of the Second Dynasty were interred in Abydos, including Narmer/Menes. These were the first true mastabas, as they were bench-like structures built on top of brick chambers that were in large pits. There is no doubt that the Abydos mastabas functioned as royal tombs, and as time progressed, they became more elaborate.

In addition to Narmer/Mens, Iri-Hor, and Ka, all the kings of the so-called “Dynasty 0” were buried under mastabas in Abydos. The kings of the 1st Dynasty were also buried at Abydos, near one another west of the Dynasty 0 tombs. Persibsen, the penultimate king of the 2nd Dynasty, had his mastaba located between the 1st Dynasty and Dynasty 0 tombs. The mastabas of the Dynasty 0 kings were small and modest, which changed with the mastaba of the first king of the 1st Dynasty, Aha.

Aha’s mastaba was more complex than those of Dynasty 0. It originally began as a double chamber tomb but was added to over time and eventually consisted of three large mudbrick-lined pits. Aha was probably buried in the middle pit, although his mummy was never recovered. Another innovation in mastaba building during the 1st Dynasty was the addition of a staircase. King Den’s tomb was the first to have a staircase, which made it possible to build an even deeper tomb. Seven kings and one queen built their mastabas in the northeast section of the Abydos necropolis. There is no doubt that Aha’s mastaba provided the blueprint for all later mastabas in terms of function and style. Yet when the 1st Dynasty ended, the royal mastaba building line mysteriously ended, at least temporarily.

Although the kings of the early 2nd Dynasty (c. 2890-2686 BCE) were buried in mastabas like their predecessors, most of their tombs are unidentified. Egyptologists have identified the mastabas of the last two kings of the dynasty, Persibsen and Khasekhemway, which has helped complete the link between mastabas and pyramids. Khasekhemway’s mastaba, known today as “Shunet el-Zebid,” was by far the most impressive of the two and the most important of all the Abydos mastabas.

Located just west of the settlement of Abydos, Khasekhemway’s mastaba functioned as a tomb and mortuary temple where the deceased king was worshipped. This was also the same function that the Old Kingdom pyramids served. The mastaba was surrounded by an enclosure that measured 177 feet by 370 feet internally and 400 feet by 213 feet externally. It was surrounded by a double wall of mudbrick that was 36 feet high and 18 feet thick in some places. The entire complex was 53,820 square feet in total, making it the greatest temple complex of the Early Dynasty Period. As a sign of how spiritually important Khasekhemway’s mastaba complex was to the Egyptians, it was known as the “Fortress of the Gods.” During its prime, with its large walls enclosing the mastaba, it must have truly looked like a fortress that was protecting the mummy of the deceased god-king.

Mastabas of Saqqara: Are They Tombs?

Abydos retained its importance as the home of the Osiris cult and, therefore, one of the most important religious centers in ancient Egypt. Yet, not long after Upper and Lower Egypt were unified as one state, the Lower Egyptian city of Memphis became the political capital. Known in the Egyptian language as Ineb Hedj Niut (“City of the White Wall”) or Menenfer (“Beautiful Min”), building activity shifted there at an early point. A necropolis developed on the west bank of the Nile River near the modern town of Saqqara. A row of mastabas dated to the 1st Dynasty, just north of Djoser’s Step Pyramid, has been of particular archaeological interest.

The Saqqara mastabas show a clear technical step forward in the evolution from mastaba in the direction of the pyramid. These were deeply recessed, niched mastabas that were much more complex than the pit-graves of Abydos. Based on this knowledge, many early Egyptologists, including Walter Emery, who excavated there from 1936 to 1956, believed these mastabas were royal tombs. Emery believed that because the Saqqara mastabas were much larger and more ornate than those in Abydos, they had to be royal tombs. To support this argument, Emery noted that many of the mastabas contained seal impressions of the 1st Dynasty kings. Still, not all Egyptologists are convinced.

Mark Lehner has argued that because the 1st Dynasty king’s tombs have been identified in Abydos, the mastabas of Saqqara served other purposes. It could be that the Saqqara mastabas served as cenotaphs of the 1st Dynasty kings, where their ka or spirit dwelled and could be worshiped. The Abydos mastabas, though, were where the king’s mummies were interred. Another possibility is that the Saqqara mastabas were tombs of nobles or nomarchs. Nomarchs were regional governors whose power declined when the central government was strong and increased in times of central weakness. It is important to note that although the Saqqara tombs were more ornate and the tombs were bigger than those in Abydos, the complexes were not. When the enclosures are included, the Abydos mastaba complexes were much larger.

The final mastaba of importance from the Early Dynastic period is known as “Mastaba 3038.” This mastaba was dated to the reign of the 1st Dynasty king Anedjib, but like the other mastabas of Saqqara, its owner remains unknown. Mastaba 3038 had a 13-foot rectangular pit with mudbrick walls that were 19 feet high. Most important, three sides of the mastaba were built to form eight shallow steps that rose to an angle of forty-nine degrees. This mastaba clearly represented the halfway point in the evolution from mastaba to pyramid.

The Final Step From Mastaba to Pyramid

The 3rd Dynasty (c. 2686-2613 BCE) is viewed by Egyptologists as the beginning of a new era in pharaonic history, the Old Kingdom (c. 2686-2125 BCE). Pyramids replaced mastabas as the focal point of ancient Egyptian architecture in the Old Kingdom, but the mastaba made one last important appearance.

According to the 3rd century BCE Hellenistic Egyptian high-priest of Serapis and historian Manetho, the first stone monuments were built during King Djoser’s (c. 2667-2648 BCE) rule. Transmissions of Manetho’s fragments reveal that the passage containing this information is somewhat confusing.

“Tosorthos, for 29 years. (In his reign lived Imuthês,) who because of his medical skill has the reputation of Asclepios among the Egyptians, and who was the inventor of the art of building with hewn stone. He also devoted attention to writing.”

Tosorthos is likely a garbled version of Djoser’s name, with the rest of the passage’s importance stating that Imhotep introduced stone architecture. Mastabas were primarily built of mudbrick, which is why so few of them remain to this day. Imhotep improved mastaba construction by building the first stone tomb, the Step Pyramid, and using multiple mastabas. The Step Pyramid is simply six successively smaller stone mastabas placed on top of each other to reach 34 feet in height. The Step Pyramid also expanded on the idea of a tomb complex from the royal Abydos mastabas. A 5,397-foot-long wall enclosed the Step Pyramid and its temple complex, which was dedicated to the king.

After the Step Pyramid, Egyptian architects refined the structure and created the first true pyramid in the 4th Dynasty (c. 2613-2494 BCE). However, the Pyramids of Giza and all later Egyptian pyramids would not have been possible without the development of mastaba tombs.