How should we deal with unjust laws and unjust governments when we are forced to live under them? This is the central problem of Angela Davis’ essay Political Prisoners, Prisons and Black Liberation: “Despite a long history of exalted appeals to man’s inherent right of resistance, there has seldom been agreement on how to relate in practice to unjust, immoral laws and the oppressive social order from which they emanate.” This article follows Davis’ intervention in this field, and some issues raised by it. First it explains the version of protest Angela Davis sets herself against, which we can roughly label the ‘liberal’ approach.

Then it considers two kinds of political protest – that which defies the existing legal regime and that which hopes to provoke it to action – and whether Davis is defending political disobedience of both kinds. Lastly, it concludes with Davis’ views on fascism in American society.

Angela Davis Against Liberal Activism

Angela Davis is one of the most famous theorists, writers and activists alive today. Her reputation does, of course, rest on her writing and her more conventional forms of activism, but her notoriety – among her enemies as well as those she has inspired – rests on her willingness to take more extreme forms of action. In particular, she was accused of supplying guns to a group which occupied a courtroom, a crime for which she was first imprisoned and eventually released.

The collection of essays for which the subject essay was written was put together in response to this event, and this essay can be taken to subtly reflect on Davis’ own radical protest at racism in the United States. In particular it is a defense of her methods against the more gradualist, liberal approaches to changing the behavior of states, which takes “Law and order, with the major emphasis on order, [as its] watchword. The liberal articulates his sensitiveness to certain of society’s intolerable details, but will almost never prescribe methods of resistance which exceed the limits of legality”

Angela Davis on Two Kinds of Protest

The imperative, for Davis, is “opposing unjust laws and the social conditions which nourish their growth”. Yet there is a helpful distinction to be drawn between the political prisoner who is imprisoned for crimes which are, from the prisoner’s perspective, acts of prefigurative politics, and the political prisoner who conceives of their actions as instrumental to their political cause, and not in and of themselves desirable.

This distinction would go some way to explaining two quite different approaches to the law itself. The first approach suggests that the best way to change the law is to act as though it has already been changed; to simply ignore it, to allow the law or laws which are being protested to wither away. This kind of protest seems natural when the protestor simply wants the law not to intervene in a certain instance. The second approach suggests that no such protest is possible – perhaps the power of law and its application must be redrawn, or used in some new way, rather than simply suspended.

Uses of Power

This dichotomy – between restricting the power of the law and using that power differently – is often muddled by the fact that the law entrenches or enforces power which exists independent of it. An abolitionist in the time of slavery does, of course, want those laws which allow slave owners to buy, sell and control their slaves to be got rid of. But the abolitionist also wants the law to step in, to protect slaves or former slaves from reprisals.

Indeed, the slave owning concern is powerful enough that even without the law’s backing, it can nonetheless informally sustain a market in human beings. Clearly, that two forks of a binary distinction can occur in the same cases might speak to the infirmity of the distinction. Equally, if the distinction does well in clarifying a difference – even if both sides of the dichotomy can often occur together, then it is worth preserving. Because Davis sees the state and social conditions which nourish racism within the state as fundamentally intertwined, she doesn’t preclude the use of the state for intervening in a racist society.

The Difference Between Killing and Murder

There is a further dichotomy which is important to identify explicitly. The relationship between the concepts of killing and murder is extremely complex, yet incredibly important if we wish to grapple with some of the issues raised over political disobedience, and political violence in particular.

Davis raises the issues quite explicitly:

“Nat Turner and John Brown can be viewed as examples of the political prisoner who has actually committed an act which is defined by the state as “criminal.” They killed and were consequently tried for murder. But did they commit murder? This raises the question of whether American revolutionaries had murdered the British in their struggle for liberation. Nat Turner and his followers killed some 65 white people, yet shortly before the Revolt had begun, Nat is reputed to have said to the other rebelling slaves: “Remember that ours is not war for robbery nor to satisfy our passions, it is a struggle for freedom. Ours must be deeds not words.”

Murder and the State

It is quite common to think that whilst ordinarily wrong, killing can – in certain limited cases – be justified. It is similarly common to call killing which cannot be justified ‘murder’, and to claim that some person or people have committed murder is to imply that their killing was illegitimate, a sin as much as any other wanton killing is.

The relationship between the broader class of killing and the sub-class of murder is further complicated by the fact that legitimate killing is often taken to be the right of states and states alone. Indeed, this right is at the core of one of the most famous and influential definitions of the state, which comes from the German sociologist Max Weber: “A state is a human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory”.

The implication that acting outside of the auspices of the state ipso facto (by this very fact) makes killing illegitimate is one of the views which Davis wishes to oppose, and indeed Weber’s definition is helpful in illustrating the two different conceptions of the state at work here.

Black Liberation as Self-defense

For Davis, the state is not a unified ‘community’, or at least certainly not one which contains all those who live under its rule. In the United States, the state is an instrument of particular communities or groups – the wealthy, the white, the male – and it is wielded against other communities – poor people, black people, women. The state is not intrinsically inclusive – it is something which, as Nat Turner’s words exemplify, one can struggle against and long to escape.

Davis is keen to emphasize the emptiness and the arbitrariness of permitting what we would otherwise call murder whenever it happens to happen under the auspices of the state:

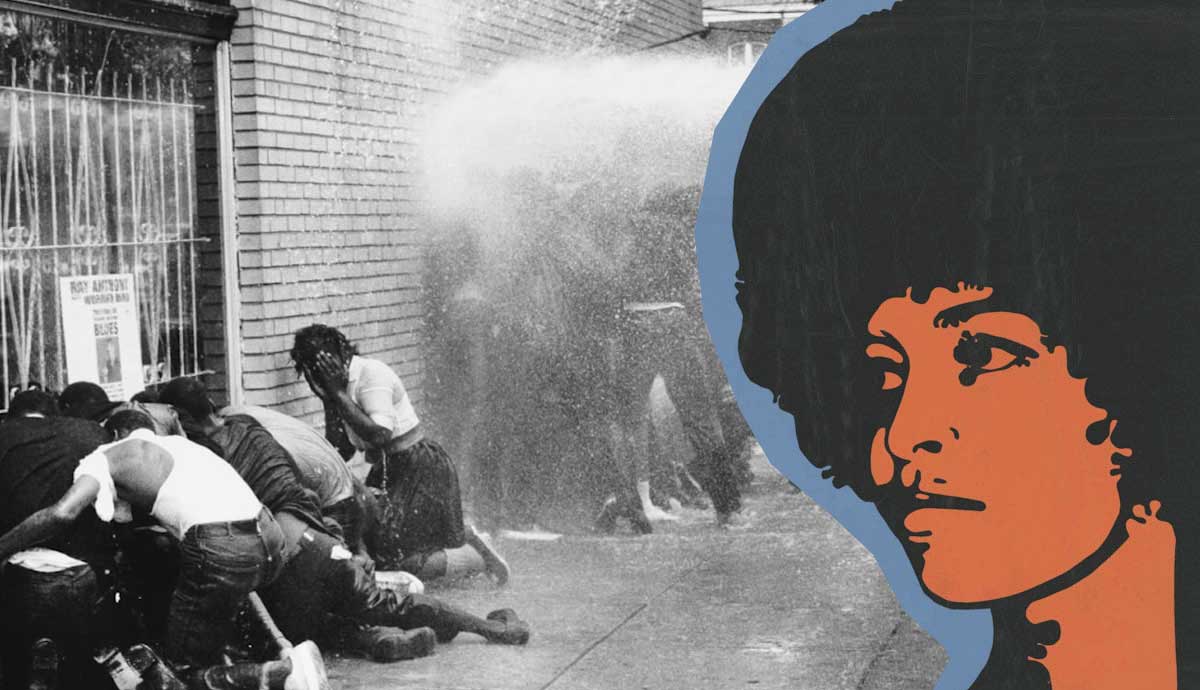

“Whenever Blacks in struggle have recourse to self-defense, particularly armed self-defense, it is twisted and distorted on official levels and ultimately rendered synonymous with criminal aggression. On the other hand, when policemen are clearly indulging in acts of criminal aggression, officially they are defending themselves through ‘justifiable assault’ or ‘justifiable homicide.”

Violence and State-building

There are good reasons to think that the relationship between violence and the state is closer and far more complicated than we are normally willing to acknowledge. Consider how often a prolonged period of political resistance and a willingness to deploy violence without the state’s permission often leads to the creation of pseudo-states.

Davis herself notes that the Black Panthers were “legitimized in the black community” by virtue of their “community activities—educational work, services such as free breakfast and free medical programs”. Those who choose to wield violence are compelled – or often feel compelled – to show that there is some kind of justification for their doing so, that they are offering something in return.

When the power imbalance between those who hold the power of violence and those who can’t is sufficiently extreme, the ‘offer’ might be rather a thin one – think of the knight who justifies the way his mistreats and abuses his serfs by claiming that he offers them protection (protection, one might think, from the knight himself).

Angela Davis on Fascism

Davis concludes her work “Political Prisoners, Prisons and Black Liberation” by talking about fascism. What she is keen to stress is that the kind of fascist government like that which arose in Nazi Germany might not appear all at once, but in stages or in degrees. She quotes Bulgarian politician Georgi Dimitrov, who argued that,

“Whoever does not fight the growth of fascism at these preparatory stages is not in a position to prevent the victory of fascism, but, on the contrary, facilitates that victory.”

For Davis, resistance up to and including violence is not only justified, but should be justifiable to almost anyone on the basis that there is a kind of incipient fascism which ‘lurks under the surface’ of American society.