The Anglo-Saxons, or the early medieval English, were a multifaceted people comprised of multiple different Germanic tribes. The label “Anglo-Saxon” has been a subject of debate among scholars, primarily due to its frequent misuse in colonial discourse. Nevertheless, the name persists as an umbrella term that refers to the original invaders of Roman Britain and the subsequent society that developed after the invasions. This article aims to explore the Anglo-Saxons through their art and material culture, which highlights the sophistication of this ancient culture.

Who Were the Anglo-Saxons?

The Anglo-Saxons were primarily composed of the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes, which were Germanic tribes from the mainland European continent that invaded Britain in the 5th century CE. It is generally thought that Anglo-Saxon rulers had taken power in Roman Britain by the year 410 (Campbell 1991), though the 6th-century writer Gildas suggested that Romans lingered in Britain until the middle of the 5th century.

By the early 7th century, the Anglo-Saxons had thoroughly settled Britain, and these settlements developed into what is referred to as the “heptarchy,” or the seven kingdoms: Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, Essex, Wessex, Sussex, and Kent. The term “heptarchy” post-dates the period in which these kingdoms ruled the island and dates to about the 12th century, but it is useful for understanding the political structure of early medieval England. Christianization also began to take place in the 7th century and slowly spread throughout the seven kingdoms.

The singular unified kingdom of England emerged in the 10th century, partially because of the rising threat of invasions from the Scots and Vikings. After a concerted effort on the part of multiple reforming kings, Edgar of Mercia became king of all England in 959 (Campbell 1991). Edgar’s reign was short-lived, as he passed away in 975. The impact of unifying England was one kingdom; however, it would last for centuries, even after the Norman conquest of 1066, which would bring about the end of Anglo-Saxon England.

Sutton Hoo: Undoing the “Dark Ages”

Before discussing the details of early English art, it is important to understand how this art and the culture have historically been viewed and how that viewpoint shifted after important discoveries made during the excavations at Sutton Hoo in Suffolk, England, in the late 1930s.

The early Middle Ages are often popularly referred to as “the Dark Ages” and are categorized as a period of cultural decline after the fall of the Roman Empire, when so-called “barbarians” ruled Europe. This characterization is deeply untrue but has impacted perceptions of the Middle Ages. In academic circles, however, the unearthing of early medieval English objects at Sutton Hoo was critical for shifting perceptions of the period from one of “barbaric” isolation to one of great advancement in visual culture, specifically in metalwork technologies, and of connectivity with the broader European continent.

In the late 1930s, an English landowner named Edith Pretty noticed mounds on her property in Suffolk and suspected there may be something worth unearthing underneath them. She communicated with local museums, and in 1938, archaeologist Basil Brown began the process of excavating the mounds. Brown uncovered what became known as Mound 1, the most famous of the Sutton Hoo mounds, in 1939. He discovered what appeared to be a ship burial intended for a very prominent member of society underneath. Though there was no corpse in the burial, the most commonly accepted idea is that the burial was intended for Rædwald, an East Anglian king who died in the early 7th century. The burial contained a resplendent variety of objects, the most renowned of which include a great gold belt buckle, the Sutton Hoo helmet, a set of shoulder clasps, and a purse lid, all believed to have been made locally.

Other objects in the ship are believed to have been Celtic and Byzantine in origin, suggesting that the individual buried within was well-traveled (Webster 2012). The helmet discovered is stylistically similar to Scandinavian helmets, suggesting that there was some exchange of ideas between Scandinavian and early English workshops.

Between the sophisticated nature of the local objects and the evidence of cross-cultural exchange between an Anglo-Saxon kingdom and other lands across Europe provided by the objects therein, the Sutton Hoo ship burial proved that early medieval England was not a culture-less wasteland. Rather, it was a well-connected society with skilled artisans and sophisticated trade networks.

Anglo-Saxon Metalwork

Metalwork makes up a large portion of early English art objects. Anglo-Saxon metalwork objects are often meant to be worn by their owners, consisting of things like belt buckles, brooches, rings, helmets, and fibulae. Metal objects were very intricate and contained references to power, war, and beasts. These themes would have been recognizable to an Anglo-Saxon audience well acquainted with them through proximity to battle or because such themes were also prevalent in vernacular Old English stories.

These objects were often owned by the most elite members of early English society, who could afford the cost of commissioning an artisan to make them. Many of them have been discovered in the context of burials like the Sutton Hoo ship burial, or in the context of hoards, like the Staffordshire Hoard, which is the largest hoard of Anglo-Saxon metalwork ever found, containing over 4,000 items.

Several different types of metalwork techniques are evident. Cloisonné is an ancient technique involving the use of inlaid enamel through firing. Niello is a similar decorative technique that chemically inlays a black sulfide alloy into the surface of objects through engraving or embossing to achieve a blackwork ornamental design rather than the more typically colorful cloisonné design. The Sutton Hoo belt buckle, for example, was made using the Niello technique. These methods showcase a high degree of understanding of metal and chemical processes among Anglo-Saxon artisans, enabling them to produce very delicate work.

Illuminated Manuscripts

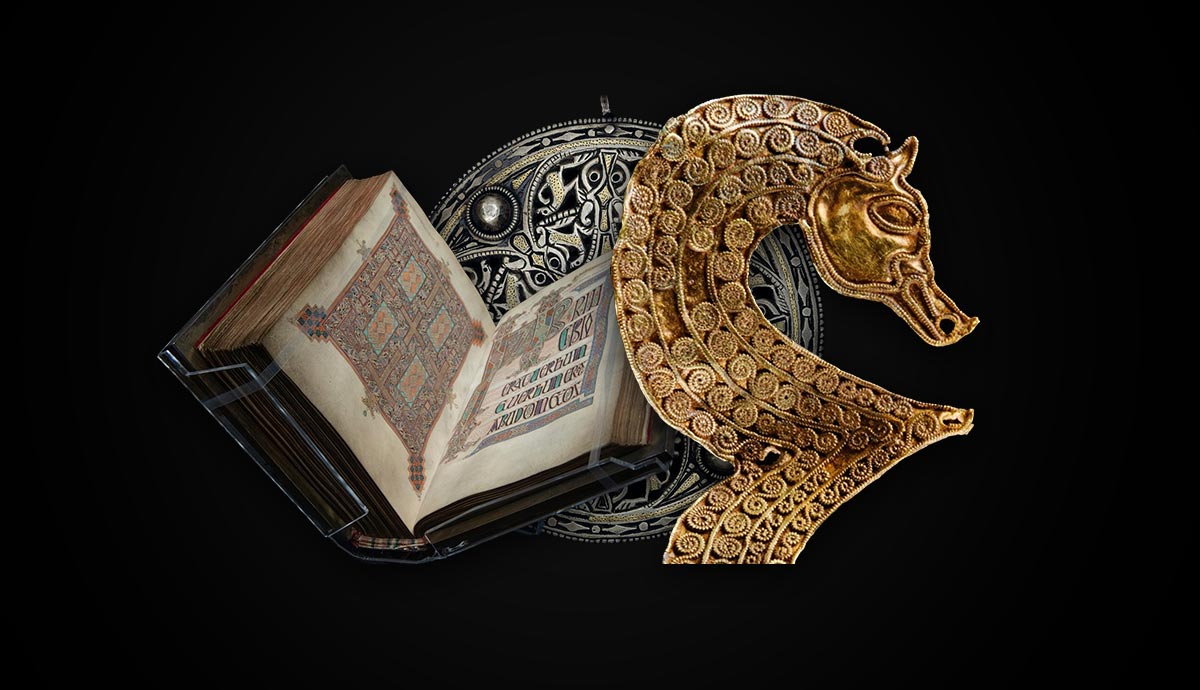

Illuminated manuscripts from early medieval England reveal much about cross-cultural exchange, especially between the Irish, the Picts, and the Northumbrians, in developing what later became known as the “insular” art style, or the art of the islands (Brown 2016). There is much overlap in style and evidence of cross-cultural influence.

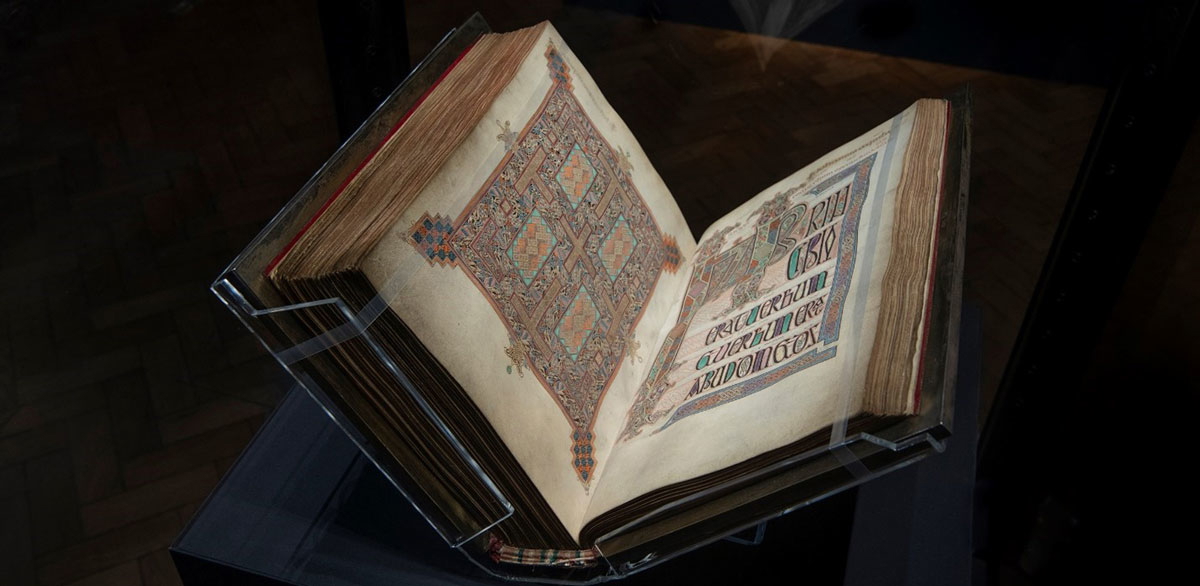

Illuminated manuscripts often contained carpet pages, which were full-page decorative illustrations featuring interlace patterns and ornamental spirals. They were designed to recall earlier patterns from the Celtic and late antique worlds and to evoke vegetal motifs. These pages also often included tiny figures of abstracted beasts. Carpet pages were meant to encourage the viewer to have a contemplative devotional experience as they attempted to navigate the complicated patterns set before them.

Decorated incipit pages, on the other hand, were the opening pages of texts, often the Gospels, and featured major initials and display scripts that were ornamented with elements like those found in carpet pages.

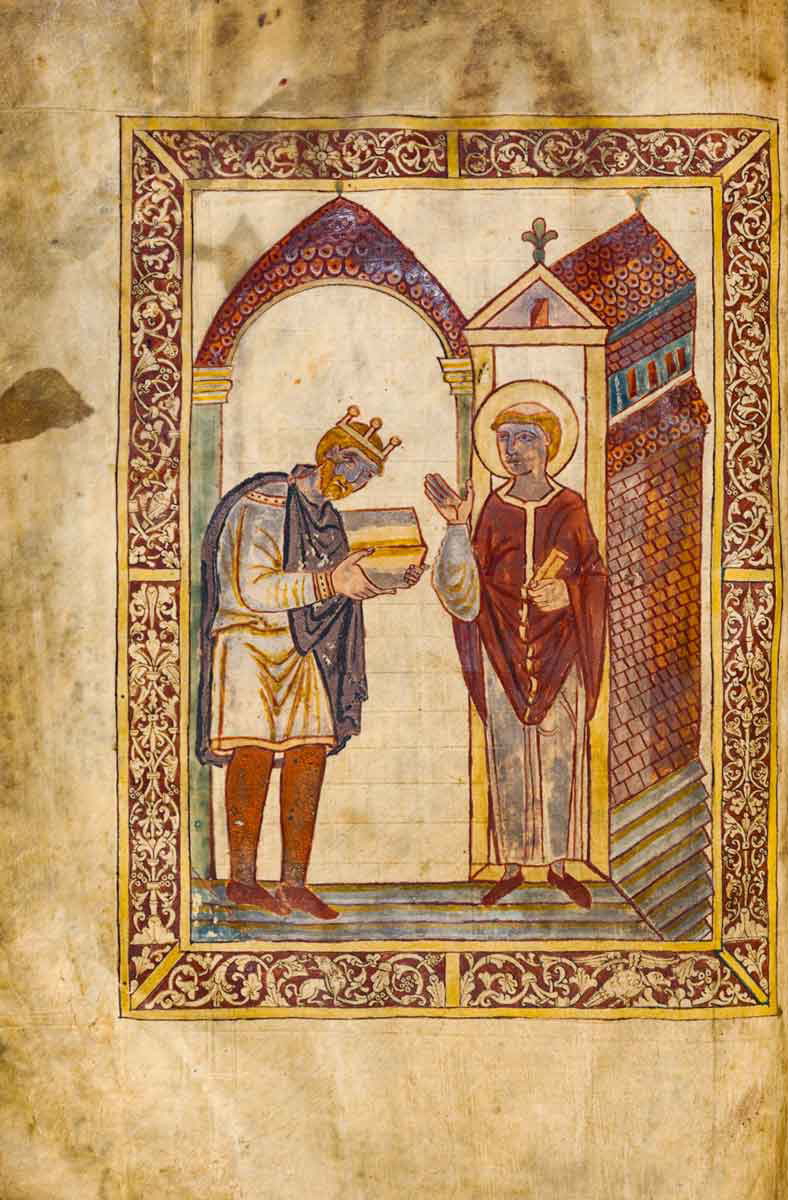

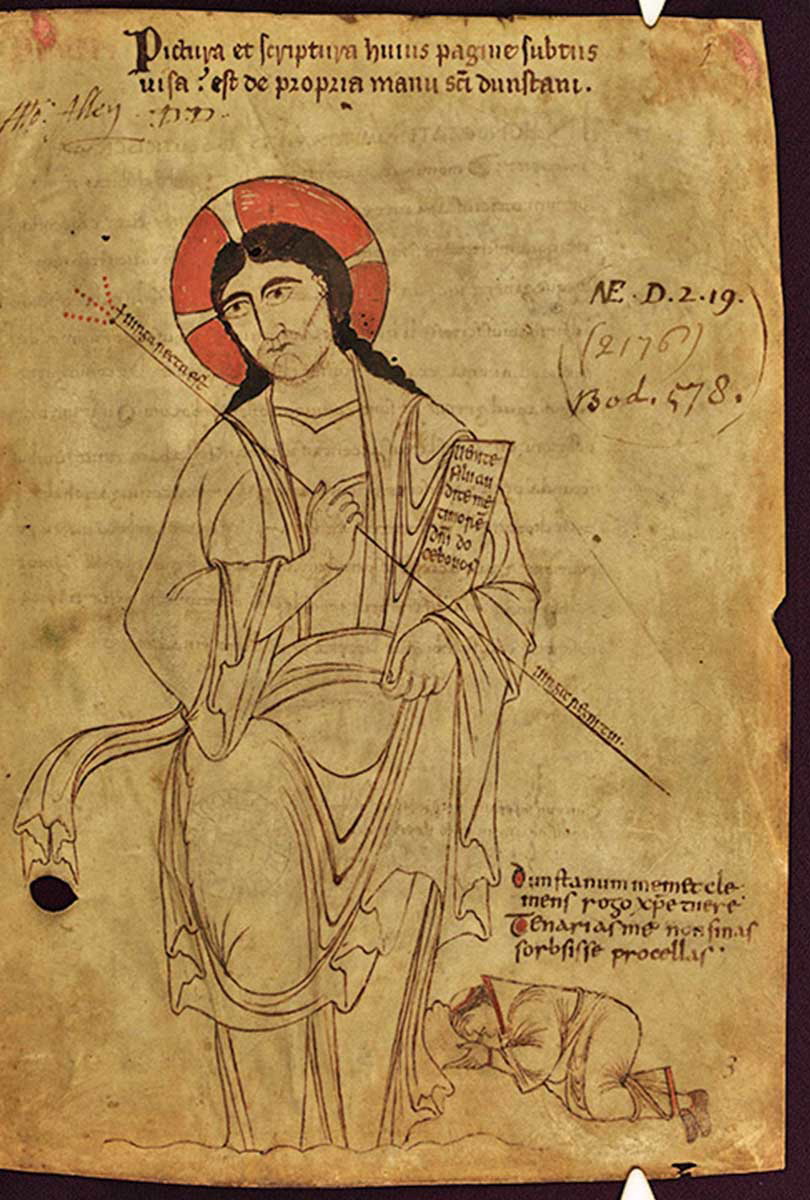

Insular manuscripts were made at scriptoria in monasteries or secular workshops in later centuries. They were often produced by the monks and nuns inhabiting the monasteries. They were made from parchment, which was produced from animal skins, and most frequently from vellum, which was calfskin. There were developments in style in the later Anglo-Saxon period, particularly during the 10th-century Benedictine reform movement, which encouraged a flourishing in art. This can be seen in manuscripts in the introduction of the so-called “Winchester style,” among other elements (Webster 2012).

Later, Anglo-Saxon manuscripts saw movements away from insular interlace towards finely detailed line drawings and elaborate miniature paintings. These developments expanded outwards from the Isles to impact artistic production in places like Normandy.

Stone and Ivory Sculpture

Scholars have written that Anglo-Saxon church buildings were “spiritual stages” in which rituals were enacted. Both monumental stone sculptures and small-scale ivory devotional objects were key to Christian practice in Anglo-Saxon England (Webster 2012). Much of medieval English stone sculpture was carved into the structure of the church itself and would have served a liturgical purpose during the performance of the Mass.

The exteriors of churches were adorned with large-scale crucifixes. There are several extant stone cross-shafts and grave markers that employed both traditional and innovative design techniques in their ornamentation (Webster 2012). Anglo-Saxon cross-shafts contributed to a broader tradition of monumental stone cross sculpture that existed in the Isles, which also included the high crosses of Ireland.

There are also several surviving examples of miniature ivory devotional objects that were likely intended for personal use, as well as other ivory objects that could have been used in the church. Medieval English ivory objects were made from walrus tusk ivory rather than being sourced from elephant tusks. Walrus ivory was brought from the Arctic region through Viking contacts (Webster 2012). These carvings were often produced in accordance with the same stylistic trends evident in manuscript production, and thus, developments followed a similar path.

Animality as a Key Theme

As mentioned above, many early English objects reflect an interest in the animal world and in the intersection of the human world with the natural environment. Animals often figure in Old English literature, whether they were beasts of battle or mythical creatures like dragons. Other texts, like bestiaries, which are collections of descriptions and accounts of animals, and the vernacular prose text The Wonders of the East (sometimes known as the Marvels of the East) featured animals prominently. It makes sense, therefore, that such interests would be reflected in Anglo-Saxon art.

Notably, depictions of animals are most prevalent on objects of adornment, particularly metalwork objects like helmets, buckles, and brooches. The Sutton Hoo belt buckle, for example, is composed of the interwoven bodies of snakes. The famous accompanying helmet features a dragon forming the outline of eyebrows, nose, and mustache. Also from Sutton Hoo, a purse lid is decorated with the figure of a man wrestling with a beast at either of his sides, perhaps revealing a more widespread preoccupation at the time of the thin line between what was human and what was beastly.

Bibliography

Brown, M. (2016) Art of the Islands: Celtic, Pictish, Anglo-Saxon, and Viking Visual Culture c. 450-1050. Oxford: Bodleian Library.

Campbell, J. (1991) The Anglo-Saxons. London: Penguin Books.

Webster, L. (2012) Anglo-Saxon Art: A New History. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.