The highpoint of the Roman games was the munera or gladiatorial combat. Though there were many types of gladiators in the Roman games, there were a few types that were more common than others and which we know more about, such as the samnite, gaul, thraex, murmillo, retiarius, and secutor. Each type had their own arms and armor, which gave each their own individual fighting style with differing strengths and weaknesses.

Early Gladiators and Basic Armor

In order to give distinct advantages and disadvantages to each combatant, a gladiatorial match was set up between two broad types of armature: the lightly armed and the heavily armed. The former offered greater mobility at the cost of more vulnerability, while the latter offered the combatant more protection at the cost of speed and agility. The purpose of pairing gladiators in this way was for the spectacle of it. After all, gladiatorial combat was an event for the audience, and the audience needed to remain engaged in the show; a pairing of similar gladiators wouldn’t have been interesting for either the combatants or the audience (Alison Futrell, The Roman Games: Historical Sources in Translation, 2006, p. 95).

Though each gladiator armature had its own specific equipment, certain items were more or less standard across all of them. The loincloth, or subligaculum, for example, was fastened to the gladiator’s waist by a belt or balteus. For the protection of the legs, cloth or leather pads called fasciae were worn.

Similarly, for the arms, a manica, a leather or cloth pad often studded with metal, was worn for arm protection. Most gladiators wore a helmet and some type of shield, though the specific types of shields and helmets varied between the armatures. The basic equipment with which each gladiator was outfitted gave at least a certain base-level protection that all armatures had in common, to prevent any given combatant from being knocked out of a fight too quickly by an indirect hit to the extremities (Futrell, 2006, p. 95).

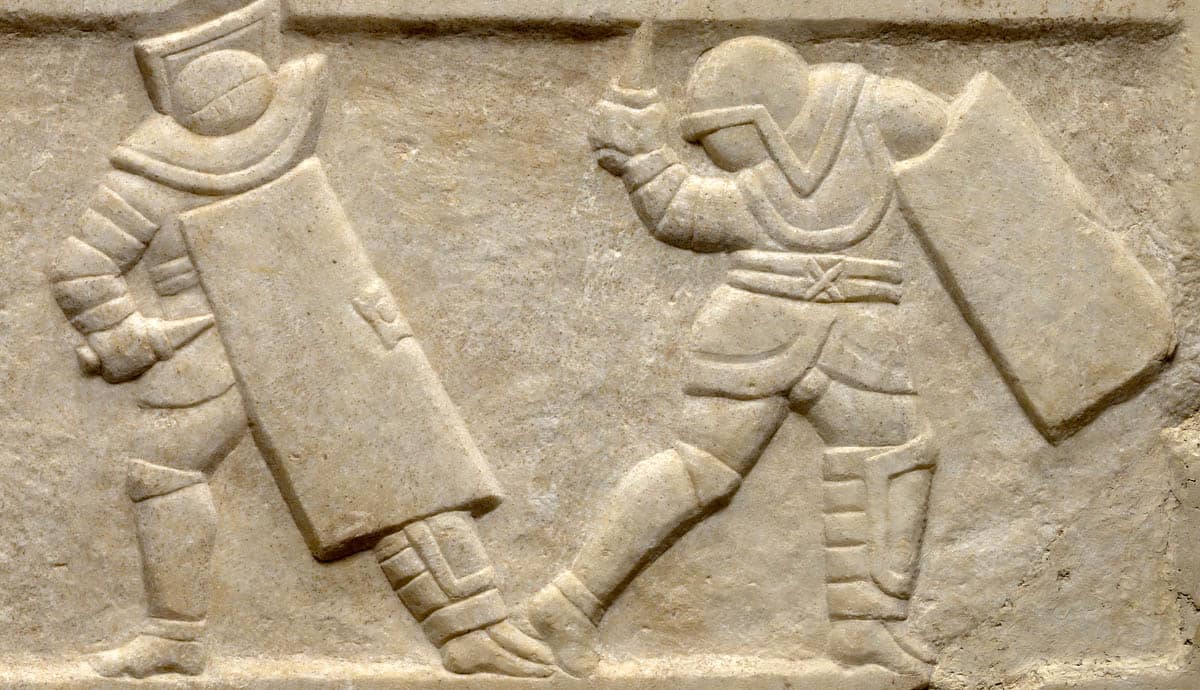

The earliest gladiators were likely prisoners of war, and with the exception of the retiarius, the Romans based most armatures on the equipment their enemies (Futrell, 2006, p. 95). As the gladiatorial institution developed, the armatures which emerged from the fighting styles of Rome’s enemies sometimes still carried the name of their national or ethnic origin: Samnis or Samnite, Thraex or Thracian, and Gallus or Gaul. The Samnites and Gauls had been enemies of Rome since the mid-Republic and were some of the earliest armatures. They were armed similarly, both carrying the basic equipment outlined above: a helmet, loincloth, a greave on their left leg, and a manica.

Each also carried a long rectangular shield and a gladius, the short sword used by the Roman infantry. During the Principate the Samnites and the Gauls had become Romanized, and so it became politically incorrect to vilify them in the arena. The armatures kept their equipment but were renamed and repurposed as the secutor and murmillo (the Gaul had a fish-shaped crest on the helmet, hence the term murmillo which refers to a certain kind of fish) (Futrell, 2006, p. 95). Some, like the essedarius, were named for their fighting style, in this case, Briton-style chariot fighting (Futrell, 2006, p. 121). The pairing for chariot fighters remains unclear.

The Thraex and Hoplomachu

While the secutor and murmillo carried a long shield (scutum) and wore shorter greaves, the thraex, or Thracian, was outfitted with a much smaller rectangular shield but longer greaves in order to compensate for the lack of the protection of the smaller shield. The thraex carried a sica a short sword with a curve at the end used for thrusting (Futrell, 2006, p. 95).

Wielding similar defensive equipment to that of the thraex (helmet with visor, manica on right arm, and long greaves protecting the legs), the hoplomachus (“shield-fighter”) was a gladiator armature which was offensively outfitted with a short, round shield, a lance, and a long dagger; it is possible that this type may have derived from the equipment used by Greek infantry (hoplites) (Futrell, 2006, p. 96). The Zliten mosaic depicts several scenes, one of which is of a hoplomachus, identified by the lance and small, round shield, as he awaits the verdict from from the referee; his murmillo opponent stands bleeding with one finger raised (ad digitum), signalling submission to his opponent and defeat to the referee.

The “Net-man”

One of the most recognizable gladiator armatures was that of the retiarius, or “net-man,” so named because of the distinctive weighted net or rete he carried in one hand; in the other, a trident with sharpened prongs and a long dagger was held (Futrell, 2006, p. 96). He was very lightly armored: he wielded no helmet, no greaves, and no shield. The manica was on the left arm, while he sometimes supplemented with a galerus or spongia, a metal guard which protected the shoulder, part of the head, and part of the neck.

The technique of the retiarius was to entangle his opponent, immobilizing him, before moving in with the trident. Given the long reach of the trident as his main weapon, it was best for the retiarius to fight his opponent from a distance (Futrell, 2006, p. 96-97). Martial claims that one particularly skilled retiarius was able to win without even wounding his opponent. Suetonius claims that Claudius liked to give orders for gladiators who had fallen accidentally to be executed, particularly the retiarius. A Roman mosaic currently in the National Archaeological Museum in Madrid shown above, depicts the fighting technique of the retiarius gladiator Kalendio.

The lower stage shows the secutor Astyanax fighting Kalendio, who thrusts his trident at Astyanax; here the manica and the galerus of the retiarius visible. Although Astyanax has been netted by Kalendio, the secutor does not appear fazed — he continues closing in on Kalendio. The upper, later half of the mosaic depicts the crucial moment when Astyanax has downed Kalendio, who is wounded (pools of blood are visible here) and raises his dagger in submission. Two arena personnel are also depicted — they raise their hands and turn towards the editor who is not shown. The editor will make the final decision as to Kalendio’s fate, and it seems he has chosen death given the null sign which is shown near Kalendio’s name, and suggests that the editor did not opt for missio in this case (Futrell, 2006, p. 98).

The Secutor

The secutor (“chaser”) and murmillo gladiators were very similar, the main difference being the secutor’s helmet, which did not incorporate a visor like the murmillo’s helmet did but instead flowed from the top of the head down to the top of the shoulders. The helmet also featured two small eye holes which allowed for limited vision, but was otherwise a smooth surface; this surface was particularly effective at deflecting the blows of the retiarius’ trident (Futrell, 2006, p. 98-99). Like the murmillo, the helmet also looked somewhat like a fish.

The major disadvantage of this type of helmet was that it would limit the gladiator’s air supply, which also tended to intensify the effects of wearing heavy armor for a long time. A mosaic from Verona, Italy, which dates to the late second or early third century CE depicts the final moments of combat for a retiarius who has been forced to his knees in submission by his secutor combatant.

The secutor was also the traditional opponent paired against the retiarius (as the alternative name contraretiarius designates). The symmetry of gladiatorial combat is well demonstrated by this pairing: the secutor took the offensive and used his shield for protection, while the retiarius tried the best he could to keep his distance so he could cast his weighted net and thrust the trident at the legs or head of the secutor (rest of the body is covered by the large shield).

As mentioned above, the downside of the secutor’s heavy armor and constricting helmet was that he would run out of breath and become exhausted if he did not strike down the retiarius quickly; if he did, the retiarius had almost no defense due to his extremely light armor. On the other hand, the retiarius must act quickly in order to tangle the secutor in his net; if he does, the heavily armored secutor is open to attacks from retiarius’ trident or dagger. Isidore of Seville comments on the pairing, stating that the retiarius is dedicated to Neptune while the secutor is dedicated to Vulcan, and water and fire are always adversaries.

The Eques Gladiator

Though visual depictions of this gladiator type show them fighting on foot, the equites fought on horseback. This armature wore a visored helmet which was decorated with feathers on the side and they carried a small, round shield. Likely, they started a fight on horseback but eventually moved to the ground once they or the opponent was unseated. A lance would have been the weapon of mounted combat, while the short sword would be used once the fight moved to the ground. This type is typically depicted wearing a tunic instead of the subligacula. Unusually, they are also shown fighting each other and not another armature, presumably because the Romans considered mounted vs. unmounted to be an unfair pairing of gladiators; the former would have too much of an advantage over the latter to be a genuine contest (Futrell, 2006, p. 99).