In an era of collapsing empires and shifting alliances, the Mediterranean in the 6th century CE was a “battleground of ambition.” The Eastern Roman Empire, based in Constantinople, was growing stronger and more powerful. Successive emperors dreamed of fully restoring the Roman Empire and its former glory. The recovery of lost territories was not merely a matter of prestige; it would also represent an ideological victory. North Africa came to represent a valuable target in that ambition. The first step toward restoring this territory to the Empire would occur near Carthage, at the battlefield of Ad Decimum.

Why Was Byzantium Fighting in North Africa?

By the beginning of the 4th century CE, the once-powerful Roman Empire had split into an Eastern and a Western part. The Western Roman Empire fell under the pressure of barbarian invasions, while the Byzantine Empire grew stronger and wealthier. At this time, North Africa was no longer Roman. The Germanic tribe of the Vandals had conquered Carthage in 439 CE, the crown jewel of the Roman African provinces. Carthage became their capital, from which they built their new kingdom.

Justinian I, who came to power in Byzantium in 527 CE, had the ambition to restore the Roman Empire, not only in glory but also in territory. By the time he took power, the Vandal kingdom was weakening, making North Africa an ideal starting point for Justinian’s conquests. Justinian also had the support of the local population in North Africa, who had traditionally been part of the Roman Catholic Church, while the invading Vandals were Arian Christians. The difference wasn’t just theological, as Vandal rulers often exiled and persecuted Catholic priests.

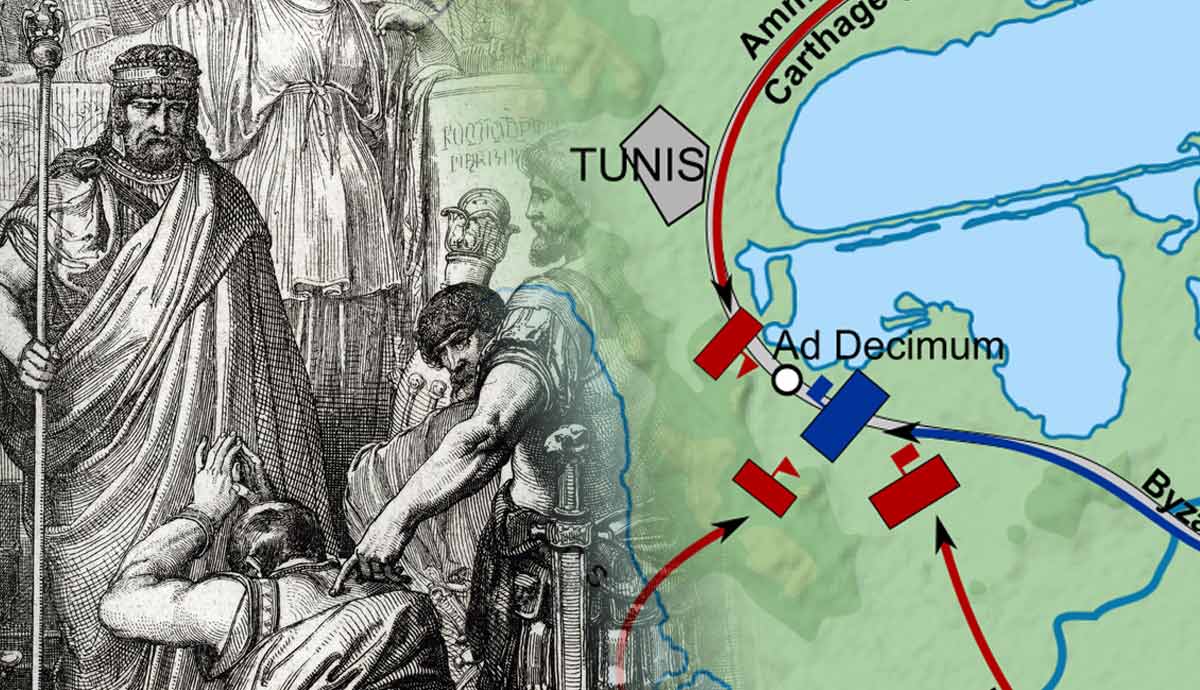

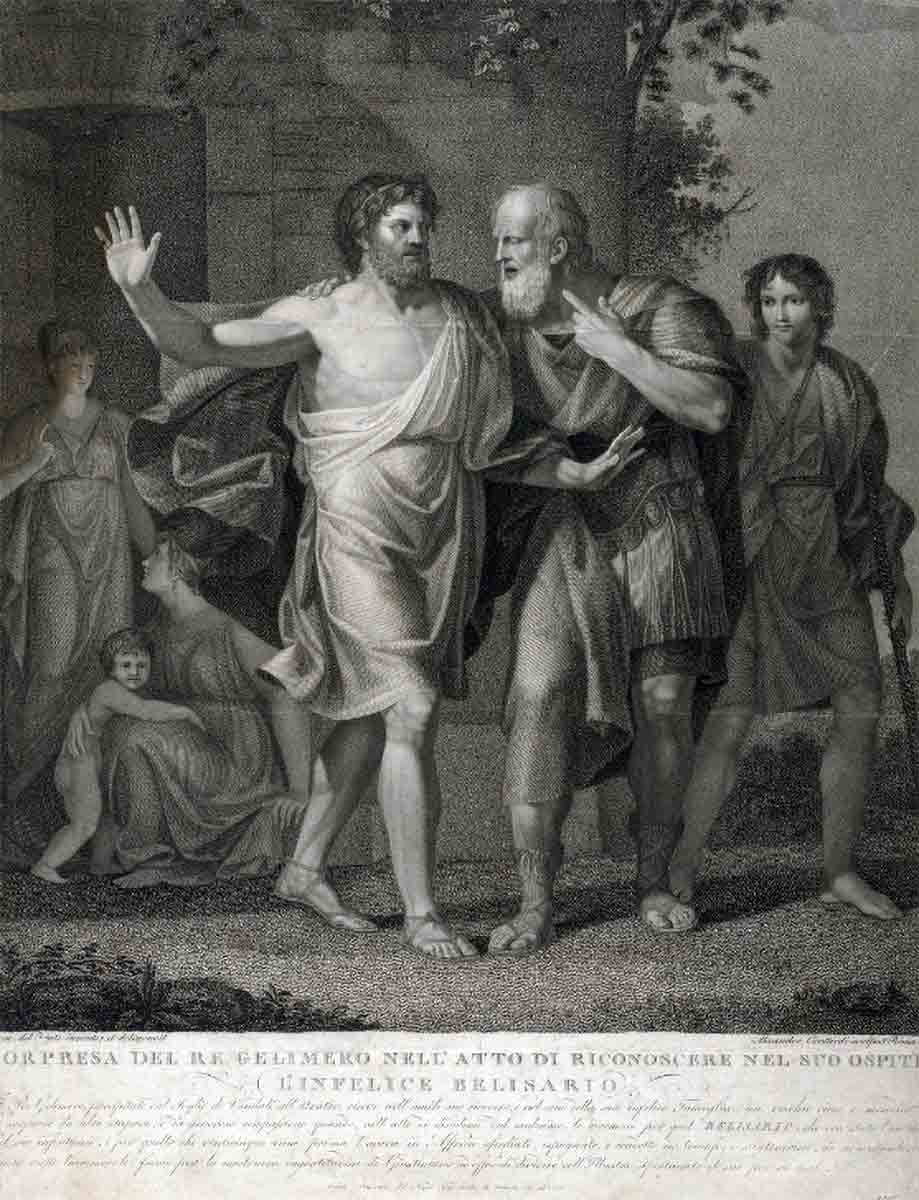

The Vandal king Hilderic had been unusually tolerant of Catholics, but in 530 CE, he was overthrown by his cousin Gelimer, who was an extremist and aimed to completely abolish the Catholic Church. Justinian saw in this the perfect opportunity, presenting himself as the protector of Christians and the savior who would restore the rightful king to the throne.

The Road to Ad Decimum

Justinian entrusted the execution of the invasion to his loyal general, Flavius Belisarius, who had previously led a successful campaign against the Persians in the East. And so, in 533 CE, Belisarius set sail for North Africa with over 15,000 soldiers, dozens of transport ships, and siege machines.

The first destination on Belisarius’s journey was Caput Vada, today’s Ras Kaboudia in Tunisia, where they anchored without resistance. Despite this initial success, Belisarius continued the march slowly and cautiously. He maintained strict discipline among his men and forbade them from looting or disturbing the local population. All of this was aimed at preserving good relations with the North African civilians, many of whom secretly hoped for the restoration of the Roman Empire.

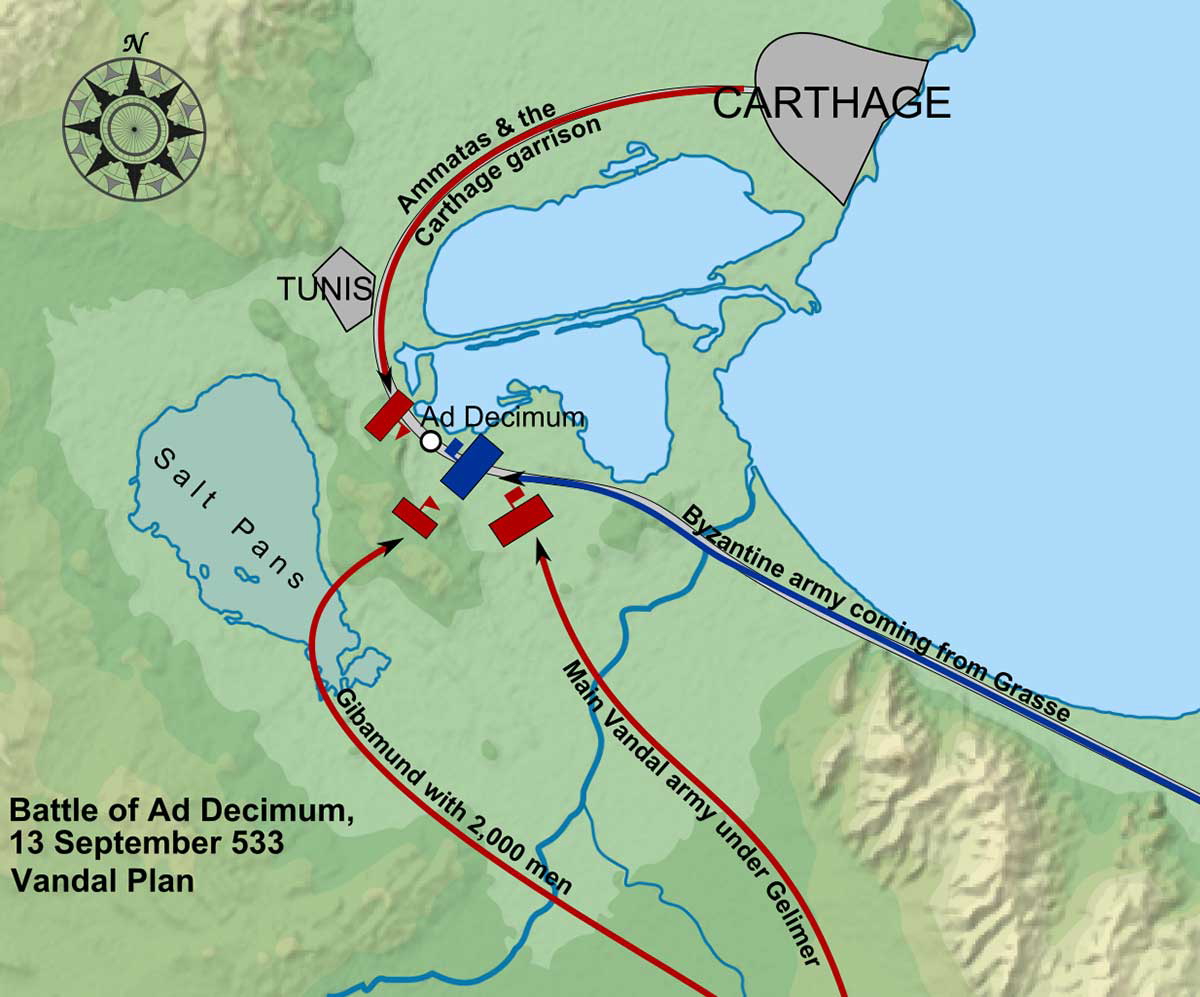

The Vandals were caught off guard by the invasion; they hadn’t expected it and were unable to regroup in time. Gelimer’s first move was to prepare an ambush south of Carthage, at a place called Ad Decimum (Latin for “Tenth Milestone”). Ad Decimum was flat and open terrain that followed the coastal road, but it featured several narrow bottlenecks well-suited for an ambush. The Vandal king chose this location because he could strike in segments, from the south, west, and north.

Despite being surprised by the invasion, Gelimer’s plan was bold. He intended to launch a multi-pronged attack in hopes of breaking the Byzantines before they could even reach the Vandal capital.

Gelimer’s Trap: A Brilliant Plan That Fell Apart

As the time for battle approached, King Gelimer sent his brother Ammatas to guard the northern section of the road toward Ad Decimum and hold off the Byzantine troops until the rest of the Vandal army arrived. At the same time, Gelimer dispatched his cousin Gibamund to launch a cavalry attack from the west. Gelimer himself would lead the main force and strike from the south. The plan was solid, but things quickly went wrong.

Ammatas arrived too early and with too few soldiers. The rest of the Vandal army was nowhere near, and his detachment could not withstand the attack of the much larger Byzantine force, which quickly crushed it. Ammatas himself was killed in the battle.

Gibamund, who was supposed to strike the Byzantines from the west, also suffered a devastating defeat. His unit was spotted by an experienced Hunnic cavalry hired by the Byzantines to assist in the invasion. In a sudden and fierce assault, the Huns smashed Gibamund’s troops before they could even reach the main road, and Gibamund was killed in the attack.

These losses were significant because King Gelimer was now isolated and unaware that the other two wings had been destroyed.

The Battle Itself: Chaos, Courage, and Collapse

When Gelimer arrived at the battlefield, he expected to find his brother Ammatas and his cousin Gibamund, but instead, he was met with a surprise. Gelimer’s plan had collapsed, and he had no choice but to face the Byzantine army in open combat. The sight of his slain brother deeply affected him, and he was unable to gather himself to lead the battle with clear judgment. His soldiers sensed this, and their morale quickly dropped.

Meanwhile, the Byzantine army was arriving in staggered formations. The first to arrive were the Byzantine advance units, which included Huns and Heruli, who immediately launched an attack. At first, the Vandals managed to resist with some success, as they outnumbered these early Byzantine forces. However, General Belisarius soon arrived with the rest of the army. The Vandals were unable to form a strong defense, and the fighting quickly descended into chaos and disorganization.

When Gelimer realized there was no hope for victory, he ordered a full retreat. He fled west into the villages of Numidia, leaving Carthage in the hands of the Byzantines. It was a humiliating defeat for the Vandals; they had lost on terrain of their own choosing and left their capital city completely undefended while their king ran away.

How Carthage Welcomed the Byzantines

Belisarius entered Carthage peacefully and ordered his troops not to loot or cause disorder. The goal was to present the Byzantines as liberators, not conquerors. The historian Procopius, who accompanied Belisarius on his campaigns, recorded the Byzantine army’s entry into Carthage. According to Procopius, the citizens of Carthage lit lamps along the city walls and houses, joyfully welcoming the restoration of the Roman Empire. Belisarius entered the city in full battle gear, not because he expected resistance, but to show who was now in charge.

“For though the Roman soldiers were not accustomed to enter a subject city without confusion… all the soldiers under command of this general showed themselves so orderly that there was not a single act of insolence nor a threat” Procopius, Vandal Wars 21.

Belisarius went straight into the palace and sat on Gelimer’s throne, where one interesting anecdote occurred: the food that had been prepared for Gelimer was now served to the Byzantine conquerors.

“He commanded that lunch be prepared for them, in the very place where Gelimer was accustomed to entertain the leaders of the Vandals… and it happened that the lunch made for Gelimer on the preceding day was in readiness” Procopius, Vandal Wars 21.

In the days that followed, Carthage began to return to normal life, albeit under Roman rule. The local population, cautious but hopeful, began to accept the new authorities.

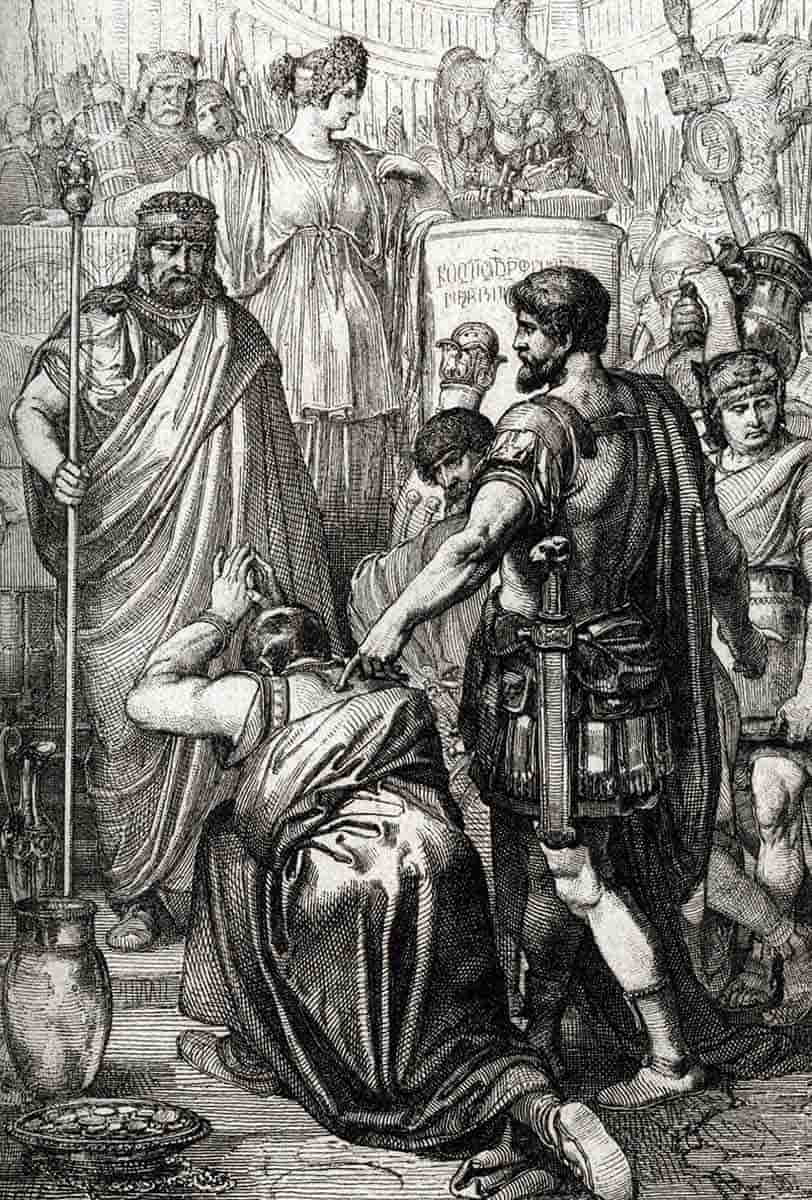

Gelimer attempted to recapture Carthage together with his brother Tzazon. With a strong army, they attacked Belisarius at the Battle of Tricamarum (December 533 CE), but suffered a devastating defeat. Tzazon was killed, and Gelimer fled into the mountains, where he hid for several months before finally surrendering to the Byzantines. He was neither executed nor imprisoned; instead, he was granted a large estate in Galatia.

Aftermath: The Beginning of the End for the Vandals

The defeats in North Africa marked the beginning of the end for the Vandals. After the final fall of Gelimer, the Vandal state ceased to exist. Procopius recorded that Gelimer did not mourn his crown, but rather his people and their fate. Byzantium had a plan for the Vandals. Thousands of Vandal soldiers were sent far to the East. Their strength was put to use, but they were kept far enough away to prevent any attempt at a coup in North Africa.

The Vandals who remained in Africa were Romanized. Within just one generation, the Vandal language, culture, and customs disappeared. This Romanized Carthage became the capital of the Praetorian Prefecture of Africa. Arian churches were handed over to Catholic priests, and the Vandal identity was erased forever.

Unfortunately, Belisarius did not have a glorious end. Although he achieved a series of successes for a time after Ad Decimum, conquering Sicily, Naples, and eventually Rome, Justinian I never trusted him. When he was supposed to retire and enjoy his accomplishments, Justinian accused Belisarius of corruption and conspiracy and had him arrested. There is also a legend that Justinian had Belisarius blinded, but the truth of this cannot be confirmed.