The Battle of Hastings in 1066 marks one of the most important turning points in English history. The Norman conquest of England changed the English population, culture, language, and its relationship with the rest of Europe. But what exactly happened during the fateful conflict? How did William, Duke of Normandy, defeat the Anglo-Saxon king Harold Godwinson to earn the title “the conqueror.”

An Empty Throne

In January 1066, the Anglo-Saxon king Edward the Confessor died childless, making him the last king of the House of Wessex. In his last moments, Edward pointed to Harold Godwinson, England’s most powerful earl. The nobles took this as a sign that he was the nominated successor and proclaimed him king. However, a comet soon appeared in the sky, a sign that trouble was coming.

Harold knew he was not the only powerful ruler with a claim to the English throne. His chief rivals were Harald Hardrada, the fearsome king of Norway, and William, the canny and ruthless Duke of Normandy. Harold had met William when he was shipwrecked in France in 1064. Norman chroniclers subsequently said that he had been sent by Edward to offer William a succession agreement, though there are many possible reasons for the trip. Regardless, William and the chroniclers alleged that Harold swore an oath to uphold William’s claim to the English throne on sacred relics.

The Last Successful Invasion of England

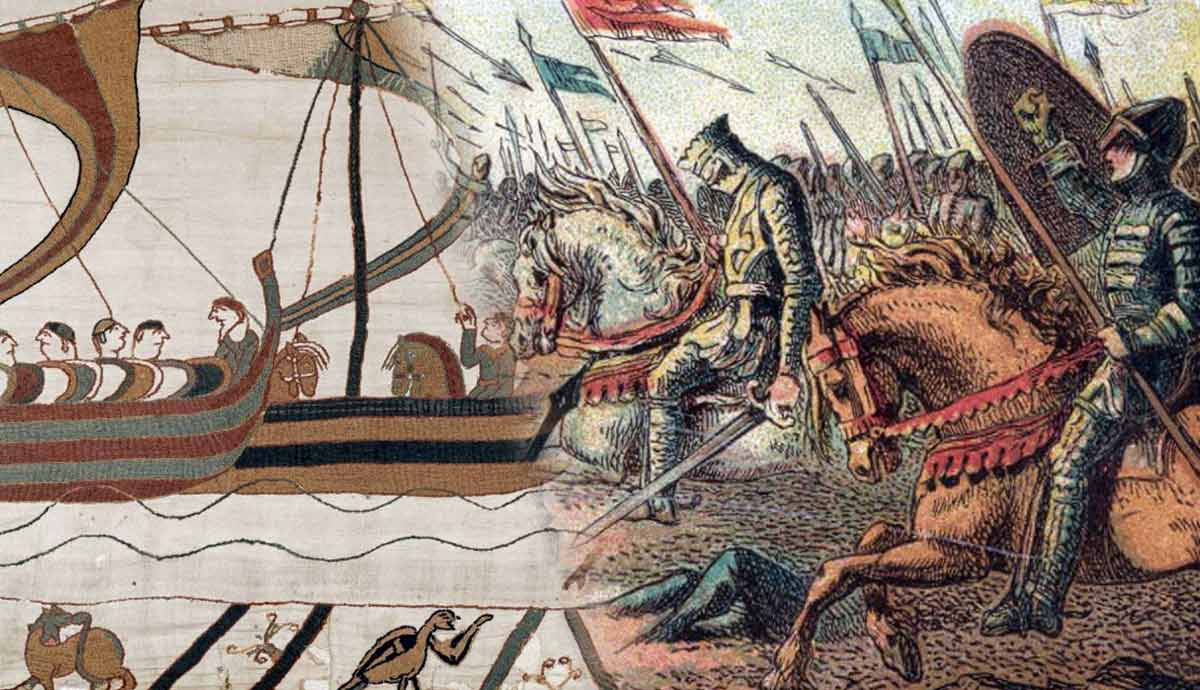

William found out about Harold Godwinson’s accession while hunting and flew into a rage. He rode back to his court and ordered a huge fleet built. He also sought the backing of the Pope, alleging that Godwinson was an oathbreaker and that the English church had fallen into evil practices. The Pope endowed William with his personal banner to use in battle.

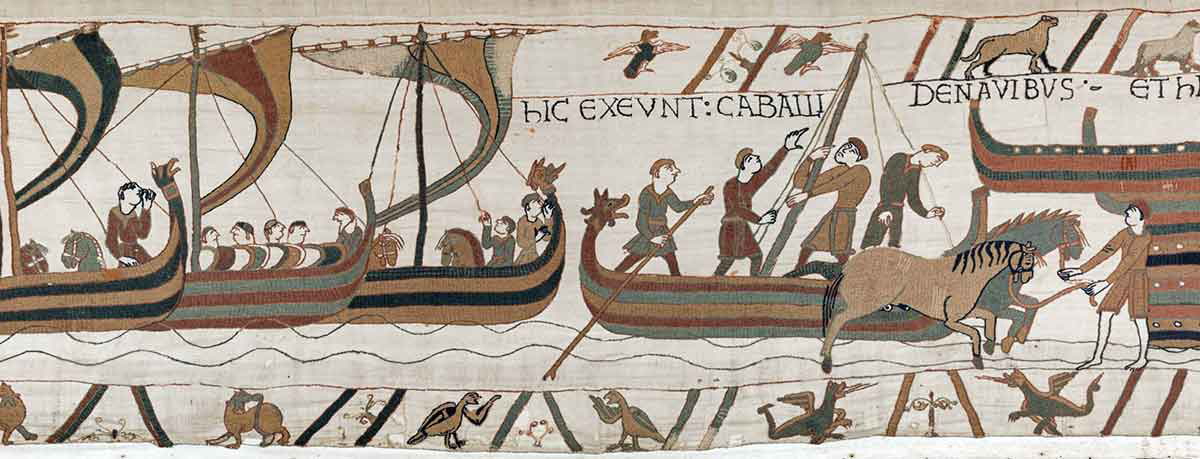

William’s main problem, as it would be for other prospective conquerors of England, was the weather of the English Channel. The fleet planned to launch in early August 1066, but was kept in port by unfavorable winds. On the other side awaited the English fyrd, of the Anglo-Saxon militia, arrayed on the southern coast, ready for him.

As the days wore on, waiting for signs of the Norman fleet, pressure grew to disperse the English army to collect the harvest. By September 8, Godwinson relented and dispersed his army. A few days later, he learned that his brother, Tostig, and the Norwegian king Harald Hardrada had landed in Northumbria. He speedily recalled his forces and marched north. The way was open for William, if only the wind would change. It did, just after the Battle of Stamford Bridge, and the Normans landed at Pevensey on September 28.

Setting the Stage

The Normans did what they did best and immediately built a castle at Hastings, providing them with a base to ravage the countryside in order to source supplies, intimidate the people, and provoke Harold Godwinson into battle. Harold had marched south as quickly as he could but stayed in London for a week, waiting for an opportunity to strike with the same surprise he had at Stamford Bridge. He may have still been seeking the element of surprise when he took up position at Senlac Hill, blocking the road to London. William was not surprised, however, and willingly advanced towards him.

The English occupied the ridge of the hill. Below, between them and the Normans, was marshy ground. At their flanks were woodland and streams. All were problems for the Normans’ greatest asset, which was their cavalry. The English just had to stay in position and outlast the Norman charges, crying “out, out,” and rattling their shields with their swords and axes.

The Battle for England

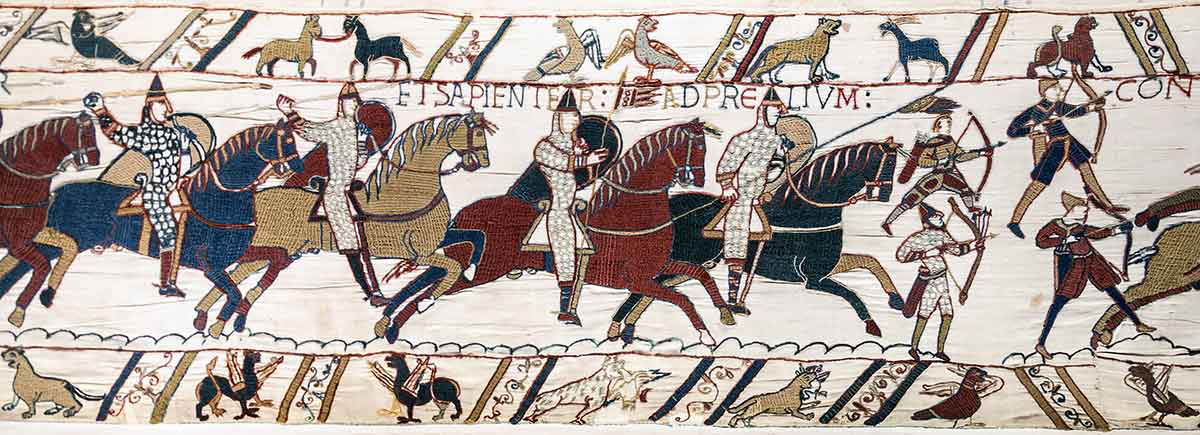

The battle began at 9 am on Saturday, October 14. William’s plan appears to have been to weaken the English with arrows, engage the English with his infantry, and then send his cavalry through the gaps. The arrows had little impact. Frustrated, the Norman infantry spearmen advanced, but were again unable to break through the shield wall. The cavalry offered support but fared little better. The cavalry retreated, and a rumor spread that William had been killed. In the confusion, a wing of the English army pursued its quarry down the hill. At this moment, William threw back his helmet, revealing that he was still alive, and his cavalry closed around the pursuing English, crushing and hacking them to pieces.

There was a battle lull in the afternoon, and William changed strategy to tease English charges with feinting retreats. This weakened the English frontline, taking out the experienced housecarls who were replaced by less battle-hardy members of the fyrd. Still, the line held. William had two horses killed beneath him while fighting.

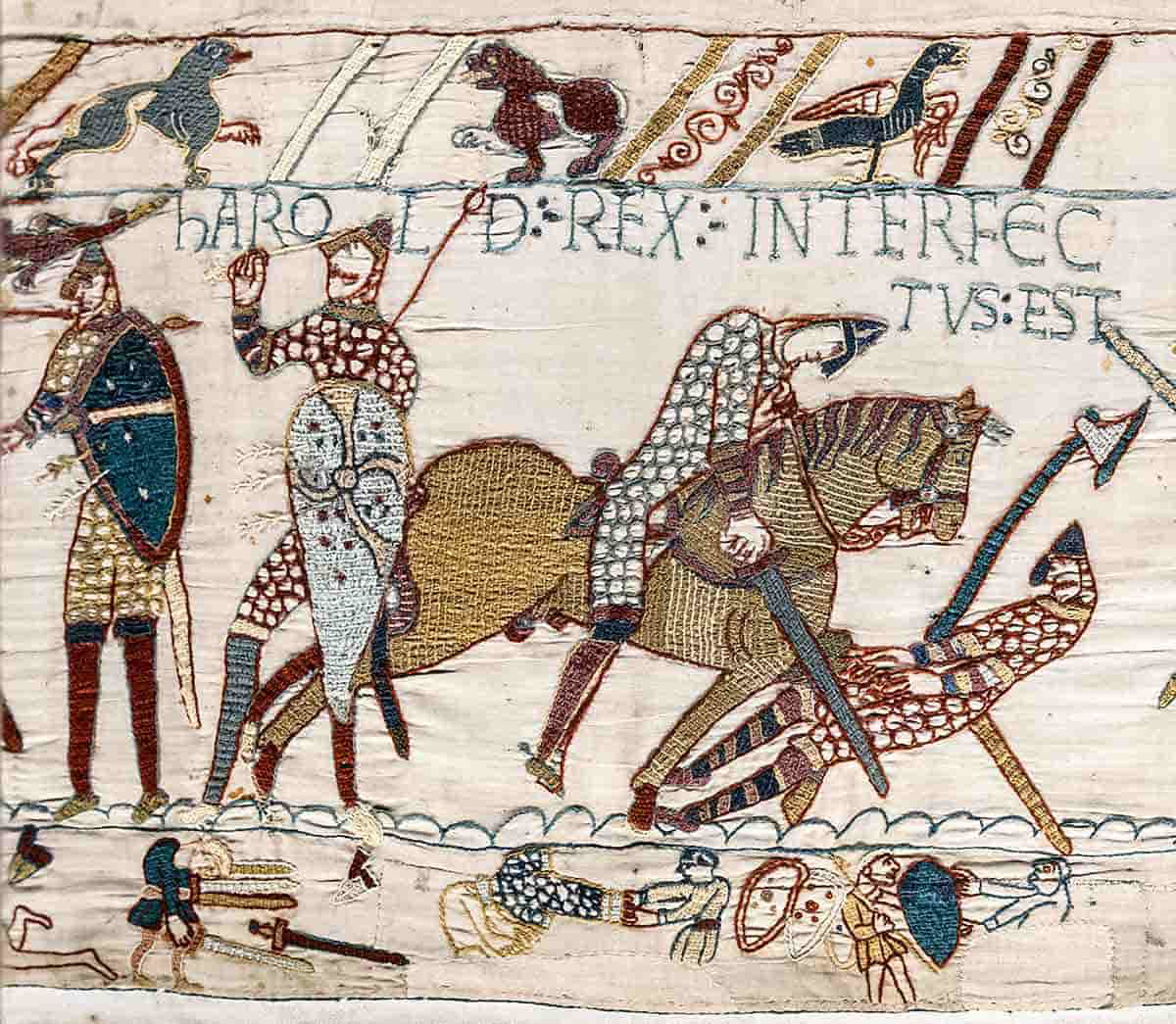

Death of the Last Saxon King

At some point in the late afternoon, Harold Godwinson was killed. It seems likely that an arrow was shot through his eye as depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry, at which point he may have been attacked by Norman soldiers. The bodies of his brothers, Leofwine and Gyrth, were found at his side, meaning either that they died earlier and were brought to him, or that they stood with him at the end. In any case, the English army appears to have begun to collapse after the death of their leader. Some stood and fought at a site known thereafter as “Evil Ditch,” implying perhaps that a massacre took place.

Perhaps as many as half of the English who fought at Hastings died, including the flower of the country’s native elite. Harold’s body was identified the following day, possibly by his wife, Edith Swan-Neck. We do not know for sure what became of his body. William refused to allow Harold’s mother, Gytha, to give him a Christian burial. Two contemporary accounts claim he was mockingly buried on a cliff so that he could continue to guard against invasion. Many choose to believe the story told by the monks of Waltham Abbey, founded by Harold, that they found the body of the last Anglo-Saxon king and buried him there.

William expected a quick surrender from London and the remaining English elite, but they instead elected Edgar the Atheling, a descendant of Alfred the Great, as king. Nevertheless, there was no meaningful, protracted resistance. William was crowned king at Westminster on Christmas Day. Rebellions erupted throughout the rest of the decade, culminating in the bloody and tragic Harrying of the North in 1069 and 1070. As much as 75% of the population of the region may have died. Some historians have labeled it tantamount to genocide, and it has even been blamed for the North’s economic struggles to this day.

Aftermath: Norman England

It had been fashionable until recently to diminish the significance of the Battle of Hastings, suggesting that it did not fundamentally change England or the course of history. However, most scholars now agree that it is hard to underestimate the impact of the battle. The entire English ruling class, including nobles, thegns, and bishops, was dispossessed in favor of a new Francophone elite. This had a dramatic effect on the distribution of land and wealth, the class structure, and the language, leaving the English banished from government until the 14th century. The English became second-class citizens in their own country and would remain so for some time. It also changed the physical landscape, as modest English churches became Gothic Norman cathedrals, and imposing stone castles began to proliferate across the country.

In the longer term, because of William’s holdings in France, England would be embroiled for centuries in the affairs of its continental neighbor. The Normans also expanded beyond the borders of England into Wales and Ireland, but more peacefully into Scotland. Some see this early imperialism, plus the competition with France, as the ultimate origins of British colonialism. In the 17th century, intellectuals began associating the Norman “yoke” with the loss of ancient English liberty, which helped inspire the English Civil War, the Glorious Revolution, and eventually the American Revolution. In many ways, then, the implications of this ancient battle still reverberate to this day.