Despite both faiths being Abrahamic, the Christian and Muslim dichotomic relationship has yielded many conflicts through the historical narrative of both the Western and Eastern Worlds. Dominant Christian ideology in Europe led to varying attempts by Europeans to conquer the biblical Holy Land. Why is Europe majority Christian? Why was the geopolitical climate in Europe so categorical? The Battle of Tours is one of the earliest recorded conflicts between Christians and Muslims. Fought in 732 CE, its outcome largely shaped the geopolitics of Europe and the Roman Empire at the time, which still ripple into today.

Paganism: Before The Battle Of Tours

As with much of European pragmatics, the religiopolitical identity was shaped by the tumultuous political entity that was the Roman Empire. In the wake of the lifetime of Jesus Christ, the spread of his eccentric cult within the empire became a thorn in the side of its pagan imperial administration. Roman Emperor Constantine the Great (born Flavius Valerius Constantinus) would be the first emperor to issue official legal toleration of the Christian faith within the borders of his empire when he promulgated the Edict of Milan in 313 CE.

Ten years later, Constantine would take his toleration of the Christian faith a step further and declared it the official religion of the empire in 323 CE. Constantine’s personal conversion to Christianity, however, is disputed.

Over a century later in 476 CE, the Roman Empire fell (in the west). The pagan ‘Barbarian’ tribes that sacked the empire from the north discovered the vast Christian culture, ideology, and architecture left behind by the failing Roman Empire. Seeing themselves as the heirs to the cultural powerhouse that was Rome, they adopted Christianity.

The faith sustained and spread through Europe like wildfire; a wildfire that burns to this day in both Europe and its former colonies.

The Spread Of Islam In The South

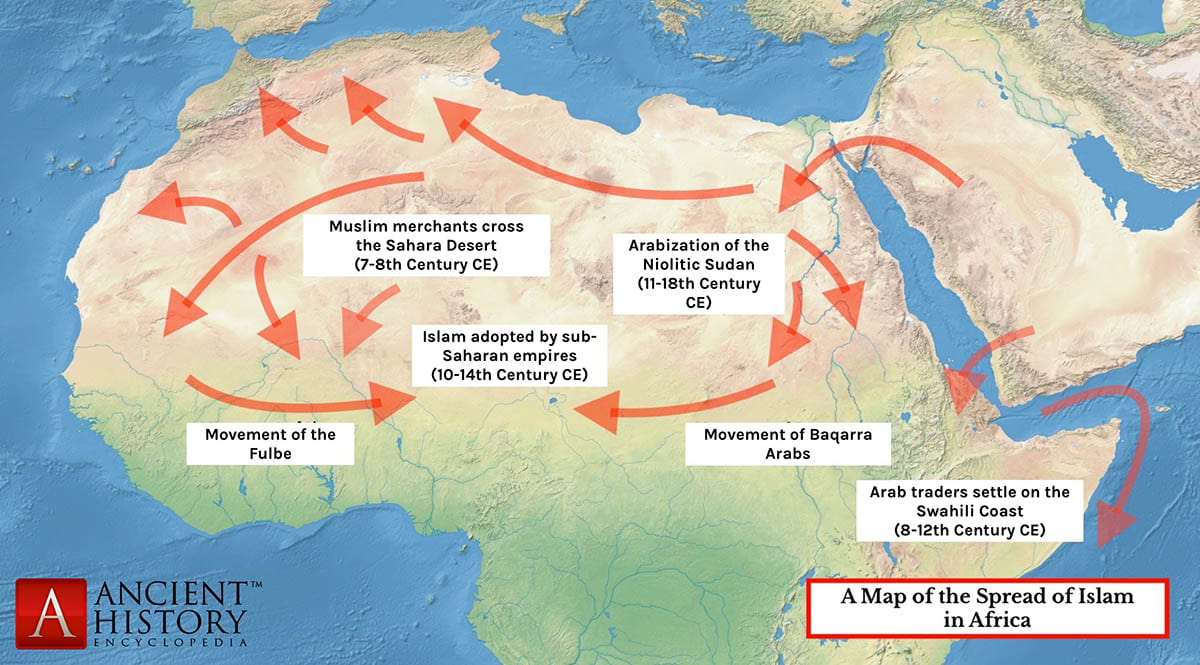

To the southeast, the Islamic faith spread through the Arabic and African continents with unprecedented speed. When the Islamic prophet Muhammad died in 632 CE, his successors spread his ideology via word of mouth. The practical and peaceful ideology proved malleable enough to comfortably adapt to any pre-existing culture it was carried to.

Traveling merchants carried the faith via word of mouth from the Arabian Peninsula across North Africa within less than a century of Muhammad’s death. These merchants carried exotic spices from the eastern Arabian world into Africa in addition to their newfound Islamic ideological mindset discovered in the East. With the Islamic faith also came the arts of writing and reading. As a result, North African culture flourished.

The ideology resulted in a unification of the spiritual identity of a varying array of peoples across Africa and Arabia. Sowed from the seeds of unity arose the Umayyad Caliphate; centralized in Damascus, they brought economic stability to the growing Islamic world by minting their own coinage. It was favorable among merchants in the south.

In 711 CE, the Umayyad Caliphate crossed the Iberian Peninsula and invaded what is now southern Spain. In attacking Spain, the Moors clashed with the Visigoths – Christian western Germanic tribes. These Moors (Muslims within Iberia), or as fans of Seinfeld might know them, the Moops, managed to penetrate as far north into Europe as what is now southern France.

The Umayyads have been criticized by scholars as having hijacked peaceful Islamic ideology and forming a united Arab Empire out of varying Islamic peoples. The Spanish steppes would remain a Moorish Islamic foothold in Europe until the Spanish Reconquista destroyed it in 1492.

Us and Them: When Two Worlds Collide

From Spain, the Umayyads managed to reach far enough north to knock on the back door of what is now France. At the time, the region was occupied by one of the Germanic successor states to the Roman Empire: Francia.

Like many Germanic tribes upon the decline and fall of the Roman Empire, the Franks saw themselves as the heirs of the Romans. Those worthy of assuming the role of lords of Europe within the void political vacuum. As such, they adopted Christianity and saw themselves as protectors of the faith.

As the Islamic forces under the Umayyads penetrated Europe, Christian forces led by the Franks saw them as a hedonistic threat to Christian Europe. The two forces met between the French towns Tours and Poitiers in the Duchy of Aquitaine, in western France in October 732 CE. The Battle of Tours ensued.

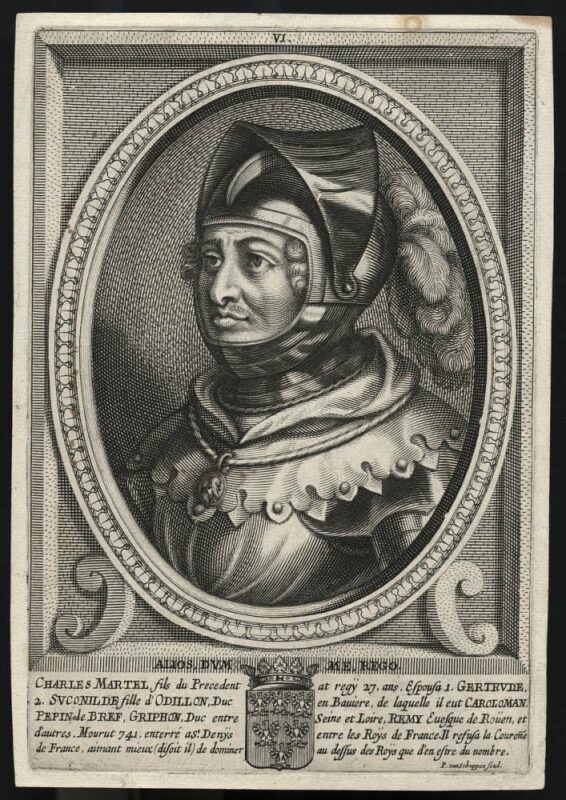

The Christian forces were formed of a coalition of Frankish and Aquitanian combatants led by Charles Martel, an illegitimate son of Pepin II the powerful de facto Frankish leader, and by Odo the Great, Duke of Aquitaine.

The Islamic forces were led by Abd al-Rahman ibn Abd Allah al-Ghafiqi, whom the Umayyad Empire had placed as governor of their holdings in the Iberian Peninsula.

The Battle of Tours

Though the exact number of troops on each side is disputed, scholars widely argue that the Christian forces were largely outnumbered. The Islamic force evidently had experience in combat and possessed an expansive sweeping nature, having walked across Africa and into Iberia with such ease. This coupled with their numerical superiority, the Umayyad troops were a force to be reckoned with.

Charles Martel, whose surname translates to “The Hammer,” played an effective defense. The Christians capably defended against the Islamic forces who so outnumbered them.

The Battle of Tours was the final one for the Islamic commander al-Ghafiqi. The commander was killed in action. The morale of the Islamic forces promptly broke, sparking a retreat into the Islamic Iberian territories after losing a substantial amount of their standing army.

Categorical Domains

From the Christian European perspective, the Battle of Tours staved a marauding Islamic force. From the Islamic Umayyad perspective, the Battle of Tours halted decades of steady advancement both ideological and militaristic.

In geopolitical terms, the Battle of Tours exposed that the Umayyad Caliphate had reached the height of its power and the extent to which its supply lines could reach. As the Empire was spread so thin, it began to gradually crumble internally. The Caliphate never managed to muster an offensive of that magnitude in western Europe again.

With Charles Martel and his Frankish kingdom firmly in control of western Europe, the Franks—predecessors to modern-day France and Germany – were set up as the guardians of Christian Europe. The Frankish victory at the Battle of Tours is largely seen today as one of the most important acts of the bolstering of Christian Western Civilization.

With his presence and power ardently established, Charles Martel successfully consolidated his reign as King of the Franks. Upon his death, his kingdom was passed onto his two sons, Carloman and Pepin the Short. The latter of the two would further solidify what would come to be known as the Carolingian Dynasty by fathering Charlemagne.

Charlemagne: Father Of Post-Battle-Of-Tours Europe

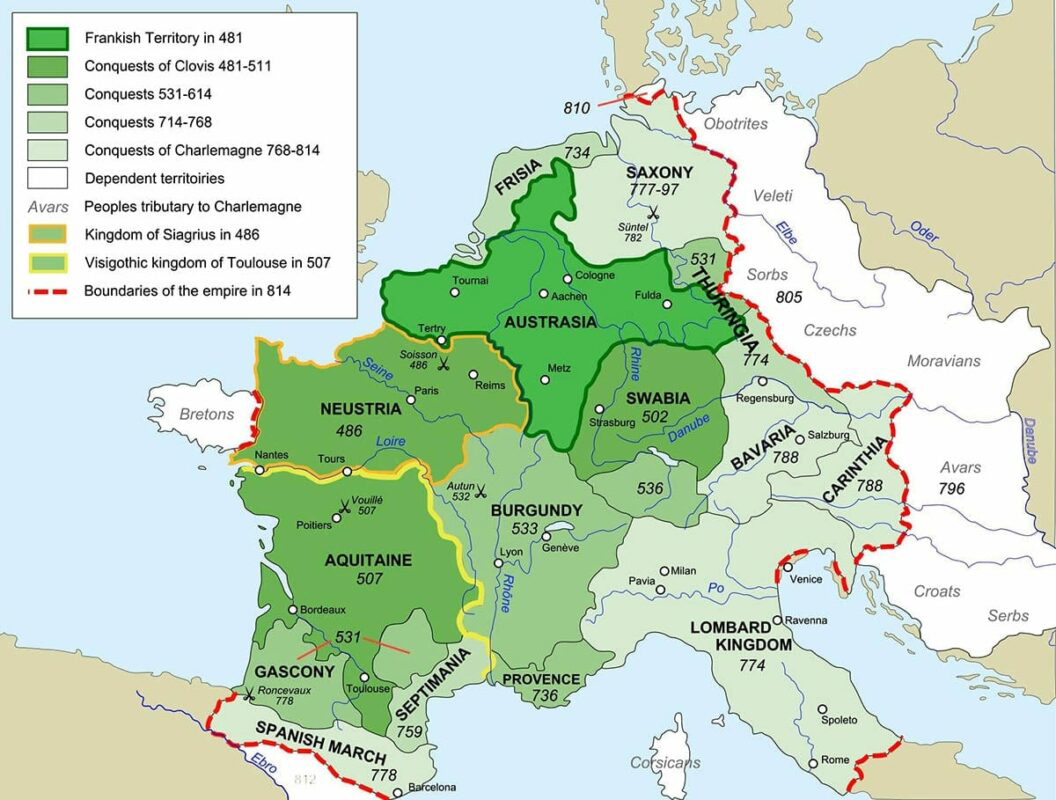

Charlemagne, whose name translates to “Charles the Great” was the grandson of Charles Martel and King of the Franks from 768-814 CE. Scholars claim that every living modern European is descended from Charlemagne and his ilk.

The expansive reign of Charlemagne brought western Europe, albeit through warfare, to a stable existence. The Frankish Kingdom extended its reach into northern Italy and further east into Germany. In Italy, though the secular Roman Empire had fallen three centuries prior, the Church of Rome clung to subsistence. On Christmas Day 800 CE the Roman Catholic Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne the first Holy Roman Emperor: Christianity now tied to a throne that had laid vacant since 476 CE. The faith manifests a secular guardian once more.

Cementing the tie of church and state, Leo III revived the Roman Empire, handed it to the most powerful Germanic kingdom, and added the preceding “Holy.” Papal politics was directly tied to secular politics.

In a series of events triggered by Charles Martel’s victory at the Battle of Tours, The Kingdom of the Franks had now quite literally eclipsed its Roman predecessors. Charlemagne, a German-speaking Christian, sat on the revived throne of the Roman Emperor.

The Holy Roman Empire was evidently buttressed by the Catholic Church in Rome, and the Church buttressed by the Empire. The realm of Charlemagne was now set up as the hub of Christianity in western Europe.

King, Crown, And Cross: Politics After The Battle of Tours

The monarch “Leviathan” holding the bishop’s crozier and the sword: the ever-symbolic mark of the unification of Church and State in western political theory.

Having cemented his alliance with the Roman Church, Charlemagne solidified his position in western Europe. The Holy Roman Empire would exert its influence on western Europe (with a gradual decline in its power) for the next thousand years.

The ripples of the Battle of Tours echoed throughout the religious historical narrative of western Europe. Had Charles Martel not defeated al-Ghafiqi, Europe surely would have been engulfed by Islamic ideology rather than by Christian ideology.

Though there would be enormous challenges to the authority of the Roman Catholic Church in western Europe, such as the Protestant Reformation (1517), the English Reformation (1534), and the Thirty Years War (1618-1648), Catholic dominance in European narrative prevailed. Starting with Frankish victory at the Battle of Tours, the Muslim defeat in 732 CE proves pivotal for the development of western European identity.