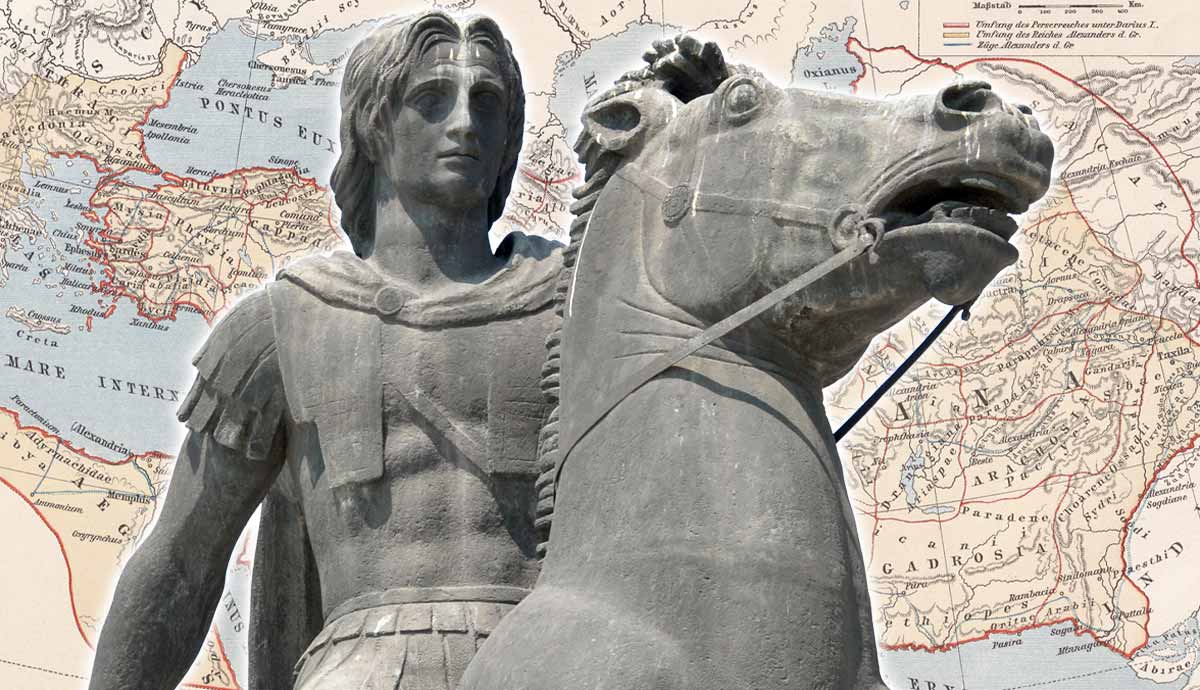

War was the defining feature of the Hellenistic World, beginning with Alexander the Great’s campaigns in 334 BCE and ending with the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE. The conquests of Alexander transformed the Greek world from one of city-states with armies of thousands to one of grand kingdoms that could mobilize tens of thousands of soldiers, elephants, scythed chariots, and warships of unprecedented size for a single battle. Not only was warfare conducted on a previously unseen scale, but it was also almost continuous. But of all the battles that took place over the three centuries of Hellenistic dominion, these five did the most to shape the Hellenistic world.

1. Battle of Salamis (306 BCE)

Less famous than its namesake during the Persian Wars in 480 BCE, this clash off the coast of Cyprus in 306 BCE was amongst the most significant naval battles of the era. The Ptolemies and Antigonids deployed some of the most powerful naval forces seen in the Hellenistic World.

By 306 BCE, Antigonus and his son Demetrius were the most powerful faction in the battle for Alexander the Great’s empire. Demetrius’ invasion of Cyprus that year continued a conflict with their rival, Ptolemy, who held Egypt and exerted influence in the Aegean and on Cyprus.

Demetrius quickly secured a foothold on Cyprus and besieged the city of Salamis on the eastern coast. Despite deploying an array of siege weapons and towers, Demetrius failed to take the city quickly. This delay allowed Ptolemy himself to arrive with 140 warships and 10,000 troops. Suddenly, Demetrius was caught between this massive reinforcement and the still defiant forces in Salamis.

While historians are confident that the Ptolemaic forces around Cyprus consisted of Ptolemy’s 140 ships plus the 60 in Salamis, the size of Demetrius’ forces is uncertain. The historian Diodorus Siculus (20.50) reports that Demetrius had around 110 warships. Plutarch’s figure of 180 ships (Demetrius 16.2). Demetrius had more of the newly developed, heavier warships, which soon became characteristic of the Hellenistic Age.

The fleets were evenly matched. However, if Ptolemy could unite his forces, Demetrius would be outnumbered. To prevent this, Demetrius risked putting himself between the two forces. He left a small force to contain the 60 ships in Salamis’ harbor and met Ptolemy further up the coast with the rest. Both Demetrius and Ptolemy placed themselves on their respective right wings, which Demetrius had strengthened with his heavier warships.

The two fleets collided, ramming and boarding across the line. Demetrius himself was said to have fought bravely from the stern of his ship as his strengthened right wing pushed through the Ptolemaic fleet. On his flank, Ptolemy enjoyed similar success, but by the time he turned towards the center, Demetrius had already crushed the remaining Ptolemaic forces. With the battle clearly lost, Ptolemy retreated and abandoned Cyprus.

The battle of Salamis was a total victory for Demetrius. A modern estimate puts Ptolemy’s losses at around 85% (Murray, 2012). The battle secured the sea for the Antigonids, but it was the broader political significance that changed the world. After the triumph, Antigonus declared himself and his son kings. For years, the Macedonian factions maintained the illusion of a united Macedonian empire. By crowning themselves, a move then followed by their rivals, the illusion of the empire’s unity was over. The Hellenistic kingdoms were officially born.

2. Battle of Ipsus (301 BCE)

The Battle of Ipsus, in modern central Turkey, shows the scale of Hellenistic warfare. The armies of four kings amassed 150,000 soldiers and nearly 500 elephants for a single day’s battle in 301 BCE.

As the most powerful kings among Alexander’s successors, Antigonus and Demetrius had many enemies. A coalition united Lysimachus in Thrace, Ptolemy in Egypt, Cassander in Macedon, and Seleucus in Babylonia against them. While Ptolemy played no active part in the campaign, Lysimachus and Seleucus, combined with forces sent by Cassander, confronted the army of Antigonus and Demetrius at Ipsus.

These were armies on a scale unprecedented in Greek and Macedonian warfare. Antigonus commanded 70,000 infantry, 10,000 cavalry, and 75 elephants. The allies had gathered 64,000 infantry, 15,000 cavalry, and 400 elephants. The core of each army remained the heavy infantry of the pike-wielding phalanx and the Macedonian cavalry. Seleucus, able to draw on the vast and varied resources of the eastern provinces, had brought a huge contingent of elephants as well as horse archers, both of whom played key roles in the battle.

Both sides deployed in a standard formation, with the infantry in the center and the cavalry on the wings. The elephants lined up against each other, but Seleucus appears to have kept most of his force, perhaps around 300 elephants, back. The battle began well for the Antigonids as Demetrius used the cavalry of the Antigonid right to sweep away that of the allied left. However, when Demetrius turned around to return to the battle, he found his way blocked by Seleucus’ 300 elephants. With horses supposedly afraid of the sight and smell of elephants, Demetrius was stuck behind a wall of Indian elephants and out of the battle.

Demetrius has been criticized for rashly charging too far and losing the battle (Plutarch, Demetrius 29.3). But modern scholars have suggested that he fell into a trap. Seleucus’ elephants were cumbersome to maneuver, and so their appearance blocking Demetrius could have been planned to follow a feigned retreat by the allied cavalry (Bar-Kochva, 1976, 109; Wheatley and Dunn, 2020, 249).

Antigonus and his infantry in the center came under attack from horse archers, who gradually began to break them. Now in his 80s, Antigonus refused to flee and instead died under a hail of javelins, still expecting Demetrius to save him. With one of its kings dead and the other forced to flee, the Antigonid army was broken, though Demetrius and the dynasty would surprisingly survive.

3. Battle of Sellasia (222 BCE)

The previously dominant city-states of Greece were much reduced but still relevant in the Hellenistic Age. Many Greek states resisted Macedonian hegemony and, at times, threatened to end it. In 222 BCE, the tangled web of Hellenistic Greek politics resulted in a decisive clash at Sellasia in the southern Peloponnese as the Macedonians and their Greek allies confronted a revived Sparta.

Antigonid Macedon’s control of Greece waxed and waned over the 3rd century BCE. The rise of federal states, particularly the Aitolians in central Greece and the achaeans in the Peloponnese, weakened Macedon’s grip. By the 240s, the Macedonians had lost key positions in the Peloponnese to the Achaeans, and the revival of the ancient city-state of Sparta further upended the situation. Agis IV and Cleomenes III used land redistribution and debt cancellation to arrest a century of declining Spartan power. Cleomenes was suddenly destabilizing the Achaeans and was close to restoring Spartan leadership of the Peloponnese. The Achaeans, with their state collapsing, were forced to turn to the Macedonian king Antigonus Doson for help.

The Achaeans had to surrender key cities to the Macedonians, but in return, Antigonus marched south and tilted the balance of the war against the Spartans. By 222 BCE, the stage was set for a battle to determine the future of the Peloponnese. Macedonian supremacy in Greece was once more to be tested in battle, while the Spartans explored whether the single, independent city-state still had a role to play in international politics.

At the approach of the Macedonian and Achaean army of roughly 30,000 under Antigonus, Cleomenes took up position at Sellasia, just inside the Spartan homeland of Laconia. Cleomenes’ efforts had revived the Spartan army, but at 20,000 strong, it was still outnumbered. The battle revolved around the two hills that stood astride the road to Sparta. The fortification of the hills helped. For a while, the Spartan army held its own. Gaps even began to appear in the Macedonian line, but these were shored up by the intervention of the Achaean cavalry. The battle came down to a clash between the Macedonian and Spartan phalanx around the Olympus hill where Cleomenes was stationed. The more experienced Macedonian line proved superior, and Cleomenes and the remnants of his army fled.

Cleomenes ultimately died in exile in Alexandria, and the Spartans would never again threaten to recover their former power. The Macedonians and Achaeans confirmed at Sellasia that the Hellenistic World was no place for a lone city-state.

4. Battle of Raphia (217 BCE)

Hellenistic battles could be spectacular but indecisive. Vast armies fought, and thousands suffered and died, all for a minor tactical or temporary advantage. The battle between Ptolemy IV and Antiochus III at Raphia in Palestine in 217 BCE was one of the largest recorded in Hellenistic history. Yet, its impact was short-lived.

Raphia was the largest battle of the Fourth Syrian War (219-217 BCE) between the Ptolemies and Seleucids. The traditional count lists six Syrian Wars spanning the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE, though one historian counts nine (Grainger, 2010), as the two empires fought for the land between northern Syria and the Egyptian border. The Fourth War saw the young Seleucid King Antiochus III capture much of Phoenicia and Palestine while Ptolemy IV’s government scrambled to respond.

For the campaign of 217 BCE, both sides mustered as many troops as possible. The historian Polybius (5.79) reports Ptolemy’s army at 70,000 infantry, 5,000 cavalry, and 73 elephants, while Antiochus commanded 62,000 infantry, 6,000 cavalry, and 102 elephants. The numbers are closely matched, but there were key differences between the armies. While Antiochus had superior elephants, Ptolemy had a distinct advantage in heavy infantry. Perhaps only 35,000 of Antiochus’ foot soldiers were heavy infantry, compared to 61,000 for Ptolemy (Bar-Kochva, 1976, 132). The Ptolemies had taken the rare step of recruiting native Egyptians and training them as a Macedonian phalanx rather than relying on Macedonian colonists and mercenaries. The move may have been kept secret, meaning that Antiochus only understood his disadvantage when he saw the Ptolemaic army at Raphia (Grainger, 2010, 213).

Antiochus’ battle plan seems to have tried to compensate but pinning his hopes on a decisive strike at Ptolemy himself. He concentrated a force of elephants and his cavalry under his own command on the right, directly opposite Ptolemy. If his weaker force could hold on long enough and he could capture or kill Ptolemy, the battle would be won.

Antiochus’ elephants overpowered their Ptolemaic counterparts, and a cavalry charge by Antiochus swiftly defeated their disorganized opponents. But critically, Ptolemy himself escaped to his center while Antiochus continued his pursuit. When Ptolemy reappeared with his phalanx, the decisive phase of the battle got underway. The superior numbers of the Ptolemaic phalanx and a victory for their cavalry on the Seleucid right crushed the Seleucid center. Antiochus saw the disaster too late and could only retreat to Raphia.

At least 12,000 men and 20 elephants died on both sides at Raphia. In the peace that followed, Antiochus lost most of the territory he had conquered but gained some important concessions. One historian has called this great battle “no more than a tactical defeat” (Grainger, 2010, 218). When the Fifth Syrian War came around 15 years later, Antiochus could look back at the bloody day of Raphia as a mere temporary setback.

5. Battle of Pydna (168 BCE)

After a century and a half of fighting each other, the Hellenistic states eventually succumbed to a new Mediterranean power, Rome. Antigonid Macedon was the first major state in the crosshairs. In 197 BCE, the famed Macedonian phalanx was beaten by the Roman legions at the closely fought battle of Cynoscephalae. Macedon recovered from its defeat, and, under Perseus, its army was rebuilt. This was just in time to face the legions again at Pydna in 168 BCE.

It seems that, while Perseus was pursuing a policy of rebuilding Macedonian power, he was not seeking war with Rome. Instead, it was the Romans and their Greek allies that initiated the Third Macedonian War (171-168 BCE). Perseus had rebuilt a Macedonian army of almost 40,000, the strongest force since the days of Alexander, but Macedon was almost alone in this war. This army fared relatively well in the war’s early, inconclusive years. It was not until the Roman forces were put under the more decisive leadership of Lucius Aemilius Paullus that the war was brought into Macedon itself in 168 BCE.

The two armies confronted each other at Pydna in Macedon in the summer of 168 BCE. They were roughly similar at 30-35,000 each, and both were built around a core of heavy infantry. Perseus’ hopes rested on his phalanx, which for more than one hundred fifty years had dominated the battlefields of the ancient world. In contrast to the massed ranks of the phalanx, the Roman legion was based on flexible units of soldiers wielding sword and shield.

The battle began almost by accident as clashes between the two closely encamped armies escalated until the whole force was involved. Paullus later admitted the fear inspired by the sight of the Macedonian phalanx advancing on him, but the Roman legion once again proved its worth (Plutarch, Ameilius 19.1). Perhaps because the battle had started by accident, the phalanx lacked cohesion, allowing the Romans to attack through the gaps in the line. The phalanx is fearsome when moving together as a unit, but vulnerable once broken up. With its cohesion broken, the phalanx was quickly butchered by the Romans in little more than an hour. Perseus’ army disintegrated so quickly that the king did not manage to get into the battle but instead fled, leaving behind as many as 30,000 dead or captured.

Perseus soon surrendered, and this time, Rome dismantled the Macedonian kingdom. At Pydna, the Roman legions confirmed their superiority, and the first steps were taken towards the end of the Hellenistic World.

Select Bibliography

Baker, P. (2005). “Warfare” in Erskine, A. A Companion to the Hellenistic World, Blackwell Publishing, pp. 373-388.

Bar-Kochva, B. (1976). The Seleucid Army: Organization and Tactics in the Great Campaigns, Cambridge University Press.

Grainger, J.D. (2010). The Syrian Wars, Brill.

Murray, W. (2012). The Age of Titans: The Rise and Fall of the Great Hellenistic Navies, Oxford University Press.

Whealey, P., Dunn, C. (2020). Demetrius the Besieger Oxford University Press.