In the 17th century, at the time of the Counter-Reformation, Rome underwent a dramatic transformation as the Catholic Church leveraged architecture, urban planning, and art to visually assert its authority and inspire renewed devotion among the faithful. In visual culture, this was achieved by evoking emotional responses and a sense of awe through grandeur, movement, light, and dramatic contrasts. It was at this time that two renowned architects—Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) and Francesco Borromini (1599-1667)—crossed paths in the city and became proverbial rivals, not only because they competed for commissions and patronage but also due to their contrasting yet equally captivating styles.

Bernini vs. Borromini

Their different approaches to architectural design are particularly visible in their domes, which played a crucial role in Baroque architecture, serving both a symbolic and a practical function. On the one hand, by towering above surrounding buildings, they facilitated mobility across the city and helped to guide the faithful towards churches—something that was crucial at a time of increased pilgrimages. On the other hand, they were symbols of the heavens and served as portals connecting the immanent world of the faithful to the divine dimension. Let’s look at how Borromini’s and Bernini’s domes came to mark Rome’s skyline with diverging philosophies, forms, and ways for the beholder to approach Heaven.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini: Grandeur and Theatricality

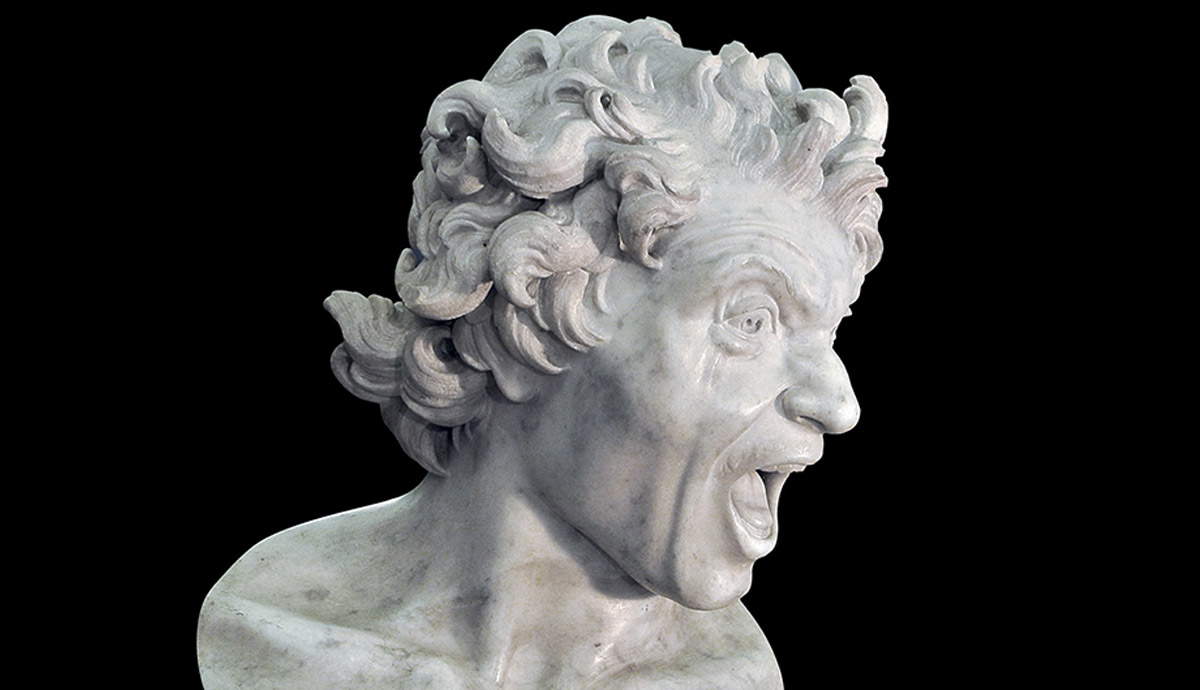

Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s approach to architecture was informed by his experience as a sculptor, artist, and stage designer. His designs focused on producing spectacular and emotionally resonant spaces, rendered through a harmonious blend of architecture, sculpture, and painting that came to be known as bel composto, a beautiful composition capable of engaging the viewer on multiple sensory levels. Bringing his sculptor’s sensibility to his architectural works, Bernini developed a style marked by dramatic forms and rich ornamentation, while his experience as a stage designer, emerging in the interplay of light and shadow and dynamic spatial compositions, bestowed to his churches theatricality, grandeur, and emotional resonance, just as if they were grand stage sets for faith to be practiced.

Bernini’s domes are a perfect example of his style and approach. His most notable work involving dome design is St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City. Although the dome itself was designed by Michelangelo, Bernini integrated it into a cohesive whole with the surrounding space. He achieved this through his design of a monumental Baldacchino, a 98-foot-tall bronze canopy placed over the high altar of St. Peter’s and serving as a visual anchor point and symbolic connection between the church’s vast interior and Michelangelo’s iconic dome above.

The windows around the base of Michelangelo’s dome enhance this interaction of elements, allowing light to flood into the space above the Baldacchino and create a dramatic contrast with its dark bronze structure. A play of light and shadows highlights the intricate ornaments that adorn it, including playful cherubs, foliage, and papal emblems. These details introduce a human dimension within the grand space, making the basilica feel more accessible and thus making the canopy act as a bridge between the dome’s massive scale and the human scale of the interior space below.

The use of light also serves to draw the eye upward from the altar, through the Baldacchino, and toward the illuminated dome, enhancing the vertical integration of the space. This sense of verticality is enhanced by means of the twisted Solomonic columns of the Baldacchino, which create a dynamic upward-spiraling motion that naturally guides the eye from the altar up toward the dome, emphasizing its importance as a crowning element and a representation of Heaven. This dynamic element reinforces the vertical thrust of the structure, making the viewer’s gaze follow from the earthly realm, represented by the altar, to the celestial realm, symbolized by the dome. Moreover, when viewed from the nave or any other part of the basilica, the Baldacchino sits centrally under the dome, creating a visual link that connects the grandeur of the dome to the sacredness of the altar.

Bernini’s design of Sant’Andrea al Quirinale (1658-1670), a church for the Jesuit order, provides another excellent example of his approach to dome design. Here, Bernini created an elliptical dome surmounting an elliptical floor plan. The interior of the church and of the dome itself reflects the architect’s sculptural sensibility and emphasis on drama, as the whole space is richly gilded, covered in polychrome marbles, and decorated with stucco elements meant to narrate a story. This dome’s design, indeed, is not just about structural innovation but rather about creating a narrative that connects the earthly with the divine.

This can be ascertained by following the depictions of St. Andrew as he ascends towards the dome, hence towards Heaven. First appearing in an altarpiece in the moment of his martyrdom, the Saint is then placed on the entablature, floating on a cloud and extending his arms upwards as he approaches the cherubs gazing down from the divine realm and surrounded by divine light, orchestrated through strategically placed windows.

Francesco Borromini: Mastering Geometrical Complexity

While Bernini’s domes emphasized theatricality, unity, and grandiosity, serving as a storytelling medium that could inspire devotion through visually interconnected elements, Francesco Borromini’s style was marked by intellectual rigor, innovative use of geometry, and a deep engagement with the spatial and symbolic potential of architecture. Mastering mathematical and geometrical principles and willing to experiment with their complexities, Borromini designed intricate floor plans, undulating facades alternating concave and convex forms, and vertiginously twisting lanterns surmounting innovative domes. Despite such complexity, Borromini’s architecture is often described as organic, as his forms seem to grow and evolve naturally and remain almost as ungraspable as the laws of nature.

Borromini’s domes are dynamic structural elements that interact with the spaces below in ways that are significantly different from Bernini’s bel composto. The dome of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane (1638-1642) is an extraordinary example of Borromini’s approach to dome design. Unlike the circular domes of traditional Renaissance architecture, Borromini’s dome is elliptical, set above an undulating and complex floor plan created by interlocking ovals, circles, and triangles. As one approaches the dome, though, the complexity of the floor plan gives way to a more regularized and simplified geometry. The central oval space under the dome is clearly defined, creating at the heart of the church a sense of calm, stability, and order emerging from the dynamic, flowing space below.

The dome itself is more regular and symmetrical, in contrast to the irregularity of the lower spaces, and is adorned with an orderly pattern of geometrical coffers that diminish in size as they ascend, creating a visual effect that draws the eye upwards towards the lantern and the light above. This transition is a deliberate architectural strategy used to guide the viewer’s attention and focus toward the central point where God is represented as a dove inscribed in a triangle, which serves as the spiritual and visual culmination of the space.

Sant’Ivo Alla Sapienza

A similar strategy is used in the design of Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza, located in the courtyard of the Palazzo della Sapienza in Rome. The dome surmounts a highly unconventional and complex floor plan based on a unique star-shaped design, formed by two equilateral triangles superimposed to create a hexagon with concave and convex sides. This hexagonal star shape, reminiscent of the Star of David, was adapted to create a three-dimensional structure offering a dynamic spatial experience. At the center of the star, a circular plan emerges, which is subtly integrated with the triangular and hexagonal forms. The combination of these shapes creates a complex interplay of curves and angles, giving the church a distinctive rhythm and flow. The interior space thus feels organic and dynamic, inviting the viewer to move around and experience it from different perspectives.

As one approaches the dome of Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza, the complexity of the floor plan’s geometry is gradually clarified. The base of the dome, a hexagonal drum with concave sides, mirrors the alternating concave and convex geometry found throughout the church’s lower walls and softens the transition from the irregular star-shaped floor plan below to the dome above, framed by a series of rib-like arches that converge at the top. The geometric clarity of the dome’s structure, with its ribbed arches and centrally focused lantern, directs the viewer’s gaze upward in a clear and unambiguous manner. This geometric simplification enhances the sense of elevation and spiritual ascension, focusing the viewer’s attention on the divine light entering from the lantern above.

While both Bernini and Borromini were innovative architects, their approaches to dome design reveal highly distinct philosophies. Bernini used architecture as an extension of his work as a sculptor and theatre designer, which enabled him to use architectural spaces as the stage for narratives meant to guide viewers along a spiritual journey. His domes are often integrated into larger, cohesive compositions that use lavish materials, dynamic sculptures, and light to enhance both the monumental effect of the church and the unfolding of the story the architect meant to narrate therein. On the other hand, Borromini had a more intellectual and experimental approach, using his knowledge of geometrical principles to bestow symbolic resonance upon his work. His domes surmount highly complex spaces that evoke the complexity of the worldly dimension, but they simplify these forms and clarify them, unveiling to the viewers the higher order and perfection of God’s created universe as their gaze approaches Heaven.